The former Latmian Gulf (now virtually closed) is a striking example of a deep marine embayment created by flooding of a low-lying coastal shelf during the pan-Mediterranean Holocene marine transgression (Figs. 7.28, 7.29). At the peak of the transgression circa 6000 to 5000 BP, the gulf may have extended 40 to 50 kilometers inland, but there is some evidence that relative sea level was actually highest circa 2500 BC (Bay and Schroder n. d.; Briickner 2003; Herda et al. 2009; Knipping et al. 2008; Miillenhoff et al. 2005). At the termination of the marine transgression, the process of infilling of the gulf by delta progradation of the Maeander (Menderes) River began, assisted by the instability

7.29 Three-dimensional map of the Latmian Gulf at maximum marine transgression, circa 4000 BP. After Bay and SchrOder n. d., fig 3.

Of the natural Mediterranean environment and augmented by variable longterm human impacts. A German geoarchaeological team placed more than 100 sediment cores in the Maeander floodplain in order to reconstruct the advancing coastline in the context of human activity (e. g., Brtickner 2003: 121—27). Using methods similar to those described in Chapter 5, they relied mainly on macro - and microfaunal analysis to determine diverse environments of deposition (marine, littoral, lacustrine, terrestrial). Radiocarbon dating of organic material furnished a chronological framework, which was supplemented by archaeological and historical information.

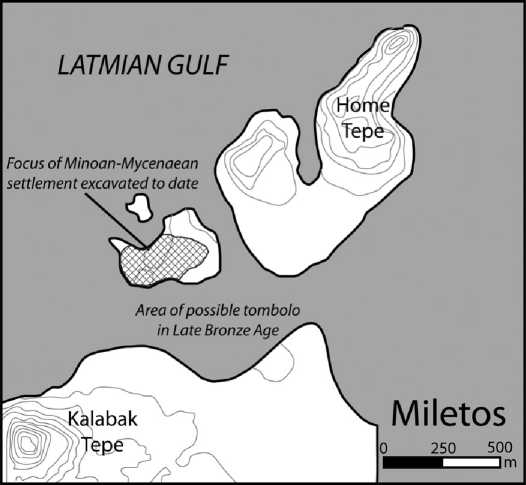

The progradation of the shoreline toward the Aegean was gradual through the Bronze Age, though a modest increase in sediment load can be attributed to the erosional effects of expanded goat herding in the second millennium BC (Knipping et al. 2008: 368, table 1). A rapid and massive increase in the rate of sedimentation occurred only in the first millennium BC (Bay and Schroder n. d., figs. 4, 5). During the Mycenaean period, the gulf still penetrated some 30 kilometers inland, and the promontory of Miletos consisted of two main islands, one formed by Home Tepe and Kale Tepe and the other the area of the later temple of Athena, which may or may not have been connected to the mainland by a tombolo (Brtickner 2003: 129—30); in short, Miletos was part of an archipelago-like coastal landscape facing onto a still-vast Latmian Gulf (Fig. 7.30).12 All around the islands and coastal areas there will have been natural anchorages and small coastal plains suitable for habitation. The climate was favorable, with moderate temperatures and adequate rainfall to support agriculture. Other natural resources such as timber and building stone were

Plentiful (Greaves 2002: 8—16). The Maeander valley was also a communication corridor connecting the sea with east-west land routes to the interior. Along those routes metals and other products from the interior of Anatolia may have been passed along to the Aegean (Greaves 2002: 32-37).

Sporadic German excavations since the beginning of the twentieth century have demonstrated that the LBA at Miletos witnessed first intensive Minoan, then Mycenaean, influence (Niemeier 1998, 2005). Early excavations established three LBA “building periods," essentially confirmed by more recent campaigns. The first building period corresponds to Minoan presence in Miletos phase IV, succeeded by Mycenaeans in the second (Miletos V) and third (Miletos VI) building phases.

Miletos V encompasses pottery phases LH IIIA1—2, from the late fifteenth to the end of the fourteenth century. Wolf-Dietrich Niemeier (1998, 2003, 2005) makes a strong case that in the second building period, there already was a Mycenaean colony at Miletos. The architectural remains are meager, and two rectilinear buildings in the Athena temple area may or may not show Mycenaean influence (Niemeier 1998: 30—31). But in other ways, the settlement is overwhelmingly Mycenaean. The pottery - including painted fineware, unpainted, and domestic coarseware — is predominantly Mycenaean with virtually no indigenous Anatolian types. Seven kilns from this period are known, including mainland Greek and Cretan types, establishing Miletos as an important center of pottery production (Niemeier 1999). Slight evidence exists for cult activity in the form of a terracotta phi-type figurine (Niemeier 1998: 33). No cemetery associated with the settlement is known. The second building period ended in a destruction dated by pottery to the LH IIIA2/IIIB1 transition, which has been linked to the Hittite conquest of Millawanda circa 1315 BC (Niemeier 1998: 38). As we have seen, scholarly opinion increasingly endorses the equations Ahhiyawa = Mycenaean Greeks and Millawanda = Miletos. Millawanda was a foothold for the kingdom of Ahhiyawa on the western coast of Asia Minor, and Miletos is far and away the most likely candidate for Millawanda, linguistically and archaeologically.

After the destruction of Miletos V and possible control by the Hittites for some period of time, the settlement regained its Mycenaean character in the thirteenth century. The third building period, Miletos VI, has yielded LH IIIB—LH IIIC pottery in large quantities, much of it locally made. Although the architectural remains have been mostly obliterated by later construction, one corridor-type building similar to thirteenth-century examples at Mycenaean mainland centers is partially preserved. A cemetery at Degirmentepe, 1.5 kilometers southwest of the Athena temple, can now be associated with Miletos VI. It includes 11 chamber tombs of canonical Mycenaean type, containing LH IIIB—IIIC pottery and Mycenaean weapons and jewelry. The evidence of cult and administration is again slight: a psi-type figurine and two pithos sherds of local manufacture

7.30 Map showing the topography of Bronze Age Miletos and vicinity. After Brtlckner 2003: 128, fig. 3.

That may have Linear B signs incised on them (Niemeier 1998: 36—37). The date of the final destruction of Miletos VI has been ambiguous, but the last Mycenaean pottery has recently been placed in transitional LH IIIB/LH IIIC Early or LH IIIC Early, which by comparison with material at Ugarit suggests a date in the neighborhood of 1185 BC, at the time of general unrest in the eastern Mediterranean (Mountjoy 2004).

Miletos was unquestionably the most important Mycenaean settlement on the coast of Asia Minor, and there are similarities in its position within the Latmian Gulf to Kolonna's status in the Saronic Gulf at an earlier time. The scale of the two bodies of water is comparable, and the role of intervisibility among the coastal settlements must have been equally important in creating a Latmian maritime small world with numerous coastscapes engaged in dense webs of interactions. Like the Saronic Gulf, the Latmian Gulf is an ideally circumscribed body of water with which to pursue a study of interaction networks at small to medium scale. A similar sentiment is expressed by Nicoletta Momigliano, based on her study of material from Iasos. She characterizes Iasos in the early LBA as a community open to maritime traffic and exchange, but acting only within a regional sphere of interaction in the Aegean; most of the pottery is of Anatolian type while actual imports from Crete, the Cyclades, the Dodecanese, and further afield are rare (Momigliano 2005). She stresses that we should pay more attention to smaller-scale exchange networks and cabotage as the chief mechanism of moving material. (Of course, this is a fundamental theme for

Horden and Purcell, and for the present work.) If sites like Miletos, Trianda, and Seraglio were the emporia of the LBA, Iasos is more representative of the kind of settlement we would expect to find at good anchorages on the shores of the Latmian Gulf.

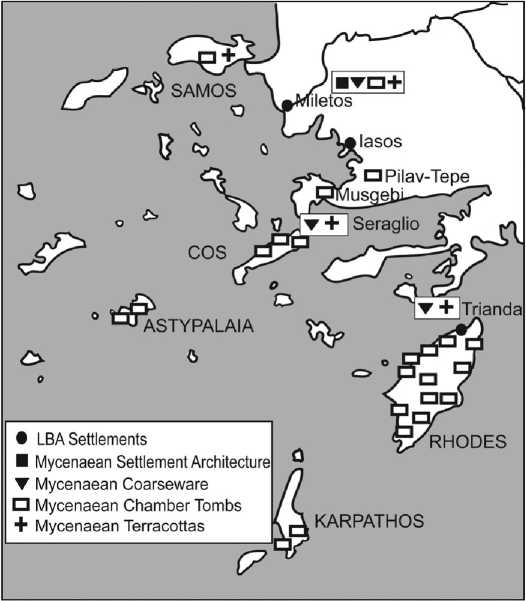

It is possible to also think about larger-scale interaction spheres into which Miletos was incorporated, thanks to a protracted dialogue among archaeologists, philologists, and historians about the nature and intensity of interactions between the Mycenaeans and the inhabitants of Anatolia's western coast. Long ago, it was noticed that, roughly speaking, the regions south of the Mykale peninsula (i. e., the northern promontory of the Maeander valley) possess a much richer record of contact with the Mycenaean world than those to the north, not only in the quantity of items but also in the presence of material categories that are deemed to reflect actual settlement or some form of engagement well beyond simple trade or episodic visits (e. g., cult objects, burial practices, domestic pottery; Fig. 7.31). The patterns are relatively uncontroversial, but some see colonies or other forms of permanent presence, while others see selective adoption or acculturation. (Compare Mountjoy 1998 And Niemeier 2005 For a sampling of the debate.)

We need not get bogged down in these issues to make the simple suggestion that the zone south of Mykale, termed by Mountjoy (1998: 33, fig. 1) the “Lower East Aegean—West Anatolian Interface," should correspond to the regional/intracultural maritime interaction sphere (see Table 6.1) in which Miletos operated. Mountjoy (1998: 47—51) proposes that this Lower Interface is the kingdom of Ahhiyawa itself. This is another, much more complex, debate beyond the scope of the present discussion (see Niemeier 1998, 2003 For the view that the kingdom of Ahhiyawa must be on the Greek mainland), but certainly the Lower Interface roughly demarcates the network in which familiar cultural materials and information moved with relative ease by sea. In LH IIIC, this zone became the core of the “East Aegean Koine" (excepting Rhodes: Mountjoy 1998: 52—63). For a Mycenaean crew departing Miletos, voyaging beyond the Lower Interface into the Central and Upper Interfaces might have been tantamount to a cross-cultural adventure, though perhaps not particularly daunting to an experienced sailor.

It is difficult to say, in my ignorance of the area, whether a targeted archaeological prospection of the former Latmian Gulf, taking as its starting point the excellent geoarchaeological work, might succeed in populating the LBA small world. Some survey work has been done, but mostly in the vicinity of Miletos itself (Lohmann 1995, 1997, 1999) and mainly with an interest in the historical periods (but see Marchese 1986). Colluvial and alluvial deposits will have buried many early sites (Greaves 2002: 40), but it is also true that Mycenaean artifacts are found on hills and in the hinterland away from Miletos, not restricted to the coast as in the period of Minoan presence (Greaves 2002: 56). It may be

7.31 Mycenaean elements in the southeastern Aegean. Drawing by Felice Ford, after Niemeier 2003: 103, fig. 1.

Interesting to attempt an investigation of some part of the lower Maeander valley from a Maritime Cultural Landscape perspective.

World History

World History