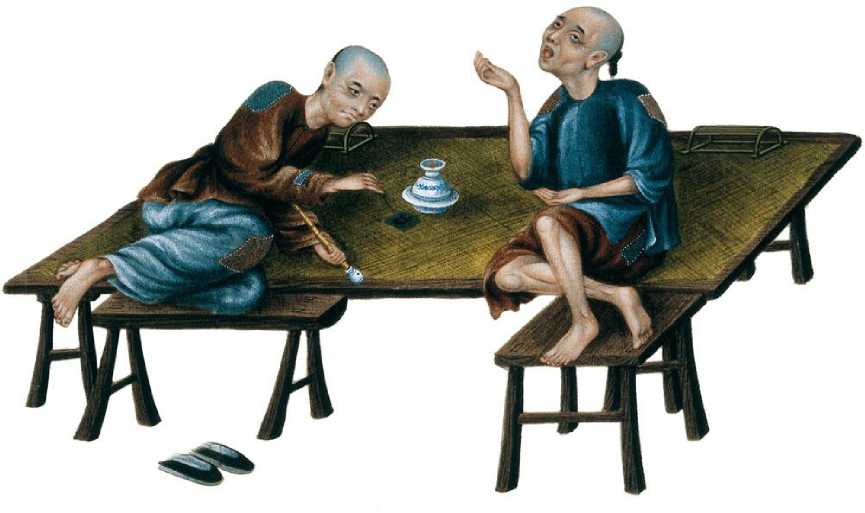

After the Opium Wars, British opium flowed freely into China, though the traffic was eroded by a boom in local poppy cultivation. By 1880 over half the opium in China was of domestic origin. The Patna product, however, was superior in quality, and the focus of a wealthy connoisseur market. It was valued for its rich resinous texture, which softened and tanned to a satisfying caramel hue when ‘cooked’ over a lamp; like wine, it matured and enriched itself when preserved in cool, dark cellars, and jars of rare vintage commanded the highest prices. Merchants and mandarins would invite their friends to visit and ‘light the lamp’ with them; fine opium, prepared over porcelain lamps with sets of silver spoons, pins and pestles by an ‘opium chef who was part of the family’s residential staff, would be smoked from pipes of ivory, silver or tortoiseshell. A culture of luxurious ‘opium houses’ sprang up, where customers could rest on sandalwood couches and soft cushions, drinking tea and snacking on sweets while staff prepared their jade-and-silver filigreed pipes. In poorer households, a pipe of home-grown opium would be offered to welcome guests; cheaper tea houses and inns would offer a similar grade, along with a simple couch and bamboo pipe, in a back room. The poorest labourers and beggars would smoke ‘dross’, the burnt residue recycled, often many times over, from the pipes of others.

As the quality of the local crop improved and plantations spread, British opium shrank to a niche product in a crowded market that was becoming a national obsession. In 1887 official estimates suggested that up to a third of the arable land in the province of Yunnan was given over to the poppy; in Szechuan two-thirds of the male population were estimated to be regular smokers. The Emperor was torn between encouraging the local product to reduce his trade deficit, and attempting to curtail the resources given over to a cash crop that paid farmers well but was becoming unaffordable to the nation as a whole. Economic decline and natural disasters were provoking food shortages and political unrest. While the rich entertained themselves in their upscale opium houses, the poor were smoking to ease the pangs of hunger or pass the hours of unemployment - and, in increasing numbers, swallowing overdoses to commit suicide.

Wealthy opium smokers (top) contrasted with poor opium smokers (above), in a pair of nineteenth-century Chinese paintings on rice paper. (Wellcome Library, London)

But in China these problems were rarely blamed on opium itself. Just as few wine connoisseurs in the modern West see themselves as responsible for the state of the homeless alcoholic, many educated Chinese saw opium as a desirable luxury with medical benefits that also happened to be a tragic last refuge of the desperate. Most users maintained a regular but modest habit of a few pipes in the evening, usually smoked in company and viewed no differently from a few glasses of claret today. Doctors continued to stress the drug’s benefits to the digestion, and the protection it gave against fevers and contagion; an elite literary culture mused on its powers to aid contemplation and the good life, and to kindle sensuality and desire in the bedroom. In times of famine, the poor were able to suppress their hunger with a pipe of dross in lieu of food; the minority who reduced themselves to dependence and misery with excessive use were not to be blamed, but nor was their opium. Just as the elderly increased their dose as terminal pain took hold, so did those who could do no better with their lot than to seek oblivion from it.

On the other side of the world, however, China’s relationship with opium was viewed very differently. To the Christian missionaries who were the main source of reportage, the nation was in the grip of mass addiction to the ‘opium scourge’. Plantations took over arable land while peasants starved; opium shops and houses in every town sapped the national economy; in areas of famine, sallow and emaciated smokers by the roadsides were visibly reducing themselves to a living death. These reports rekindled the political debate that had preceded the Opium Wars: though the foreign secretary, Lord Palmerston, had comfortably won the vote for war on the grounds of China’s destruction of British property, the young William Gladstone had pronounced the opium business a ‘permanent disgrace’ to the nation, and the Earl of Shaftesbury had called the ‘nefarious traffic’ worse than the slave trade. This had long been the view of religious groups such as the Quakers, and had subsequently gained much ground in progressive, reform-minded civil society. In 1874 this opposition was focused by the formation of the Anglo-Oriental Society for the Suppression of the Opium Trade, a coalition of Quakers and missionaries campaigning to force Britain out of the Chinese opium market, who painted a devastating picture of a nation enslaved by the ‘opium evil’. As the anti-opium campaign laid claim to the moral high ground, it became influential enough for notorious traders such as Jardine and Matheson to withdraw from the business (which had in any case become less profitable as the Chinese home-grown crop increased).

An opium den in Canton, as depicted by the London artist Thomas Allom in his popular series of engravings, China Illustrated, published in 1843-47. Allom, though widely travelled, may not have actually visited China: his opium den resembles a drunken tavern scene rather than the hushed and tranquil establishments portrayed by Chinese artists. (Wellcome Library, London)

Although opium was a familiar medicine in the West, the idea of smoking it for pleasure was novel and shocking. Like the fate of the Native American when exposed to alcohol, it suggested that certain drugs might be manageable in one culture but terminally destructive in another. Medical opinion was split. In the letters column of The Times, doctors who called it a ‘demoralizing vice’ were answered by others who insisted it was ‘harmless and beneficial’, but the profession was already abandoning opium tinctures in favour of pure drugs, such as morphine, administered by specialists.

The ‘Yellow Peril’: opium dens, and particularly the spectacle of vulnerable white women enslaved by the drug, became a staple ingredient in sensational and villainous portrayals of Chinatown, as in this poster for a Broadway melodrama of 1899. (Library of Congress, Washington, D. C.)

As well as ethical and medical concerns, the anti-opium campaign drew on a growing fear of the Chinese communities in the ports, slums and Chinatowns of the West. As the nineteenth century drew to its close, images of‘Oriental contagion’ crowded upon one another and became a staple of mass popular culture. It was the opening of Charles Dickens’s Edwin Drood, serialized in 1870, that first introduced to British readers the vision of the opium den concealed in the grim tenements of Limehouse and Poplar, around London’s docks: stinking alleys, crowded hovels and lice-infested bunks with British, Chinese and Lascar sailors huddled together while an old hag, who has over long years of debauchery ‘smoked herself into a strange likeness of the Chinaman’, tends the pipe and smears opium dross across its bowl with a filthy brooch-pin.

Dickens’s account was worked up from a visit to the home of Ah Sing, a Chinese gentleman who had arrived in London’s East End in the 1860s and was a familiar local curiosity: he had even been visited by the Prince of Wales. It was luridly illustrated by Gustave Dore, and elaborated across hundreds of fictional and faux-documentary accounts by popular writers from Oscar Wilde to Arthur Conan Doyle. Through these nightmarish scenes, the opium den became a terminus of the damned: the free-falling West End roue committing slow suicide a world away from his gambling debts and extra-marital scandals or, increasingly, the chorus girl lured into prostitution and slavery by the Chinese underworld kingpin, a character who found his fictional apotheosis in 1913 in Sax Rohmer’s The Mystery of Fu Manchu, ‘the yellow peril incarnate in one man’.

The image of the opium den in Victorian London drew heavily on the home of Ah Sing in the dockland area of Limehouse, which Charles Dickens visited before writing Edwin Drood. It was portrayed in sinister chiaroscuro by Gustave Dore (left) in his London:A Pilgrimage (1872); this oil painting by an unknown artist (right) depicts one of Ah Sing’s visitors, probably a Chinese sailor. (Wellcome Library, London)

The French colonization of Indochina was partly financed by its monopoly trade in Chinese opium, and by 1918 the government was operating over 1,500 opium dens across Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. By this point ex-colonials and merchant sailors returning to France had set up similar establishments, particularly in ports such as Marseilles and Toulon. (Wellcome Library, London)

It was in this climate of fear, and with emigration booming as Chinese workers sought to escape poverty at home, that the first prohibitions of opium were introduced. In San Francisco, where railway-building ‘coolies’ formed the largest Chinese population in the Western world, the Opium Exclusion Act of 1875 criminalized the smoking of opium by Chinese (but not by whites) after a public campaign that focused on the dangers of racial mixing, and particularly the threat to vulnerable white women. In 1887 America banned the import of Chinese opium and, as it made its belated entry into the colonial era, it exported similar prohibitions abroad. In the Philippines, annexed during the Spanish-American War in 1898, the Chinese opium trade was banned, and the drug restricted to medical use by the Philippino population. A lobby of religious voices began to press for an American-led effort to control the opium traffic by international treaty; they coalesced around the Episcopalian bishop Charles Brent, whose service on the Philippines opium commission had convinced him that ‘unwholesome pleasure-seeking’ and the ‘crude temptations of the Orient’ were corrupting both Asians and their American occupiers.

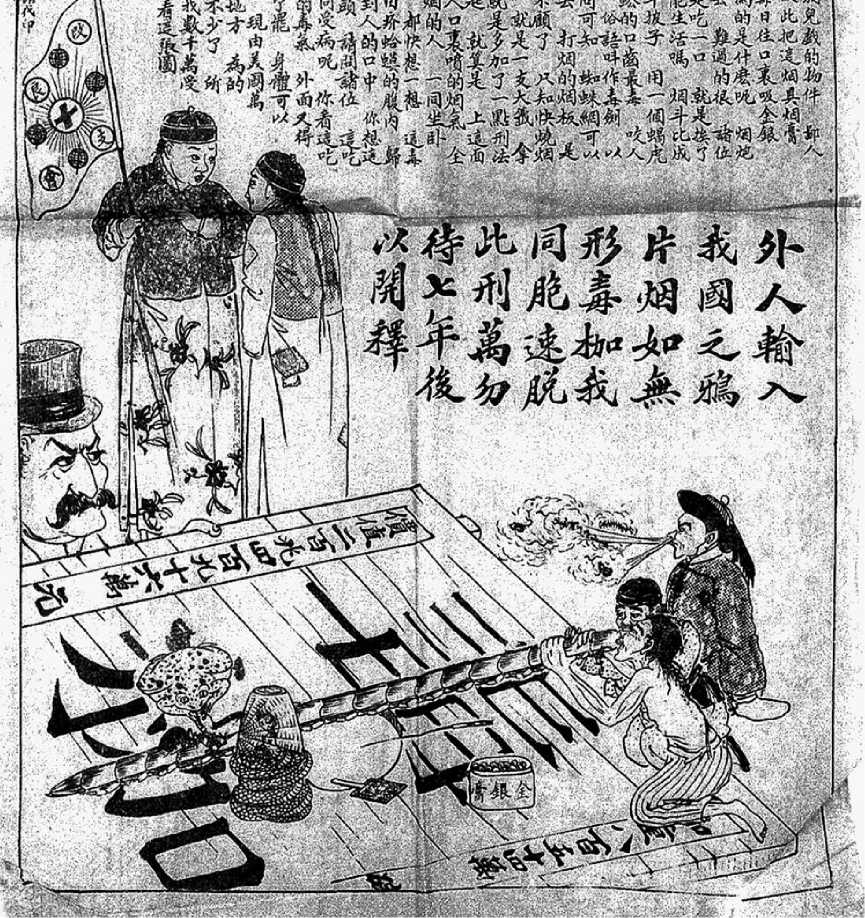

An early Chinese anti-opium poster from 1863. A toad clings to the opium pipe, the exhaled smoke is full of centipedes and the characters underneath the pipe read ‘poison yoke’. (Wellcome Library, London)

The initiative took on the dimension of a moral crusade, and was highly effective in exposing the ignoble motives of those who resisted. In 1895 Britain appointed a Royal Commission to examine the opium question. Ii concluded that a ban would be an unjust imposition of colonial authority on native interests; several Indian witnesses had argued that it would make more sense to ban alcohol to the British. But the report was easily characterized as a whitewash influenced by British trade interests, and other opium-trading nations, such as Portugal, France and Persia, were forced into justifications of the trade that sounded as specious as those of Britain half a century before. In 1909 an International Opium Commission convened in Shanghai, agreed the resolution that opiates were a grave danger’ demanding international regulation; the first International Conference on Opium, convened at the Hague in 1911 and chaired b} Bishop Brent, obliged its signatories to enact strict domestic legislation in preparation for a binding international treaty America, newly arrived on the world stage, was taking the lead in redressing the unacceptable face of colonialism.

The Republic of China, as it had recently become, was an enthusiastic participant in the crusade. The Boxer Rebellion of 1900 had been driven b}' popular revulsion against the old imperial culture: pigtails were replaced with short hair, robes with work shirts and trousers, and opium with cigarettes. The drug habit of the previous generation became the favourite symbol of Chinas humiliation by the West: ‘foreign mud’ that had been peddled by pirates and evil empires to sap their economy and reduce their population to misery. Recalcitrant opium users were forced into detoxification clinics and asylums run by missionary groups, where they were subject to various ‘opium cures’, among them the current Western trend for substituting opium with other drugs including strychnine, quinine, caffeine and particularly morphine or heroin, usually by hypodermic injection.

But the cure turned out to be worse than the disease. Just as the smoking habit had a fortuitous resemblance to native practices such as incense and moxa, the hypodermic resonated with the long-established traditions of acupuncture. Whereas Westerners found the needle shocking, in China it became an eagerly sought-after status symbol. Opium houses in the coastal cities were replaced by inns and gambling dens where shots of the ‘magic needle’ cost less than a smoke, but claimed a far higher price in addictions, and introduced previously unknown health problems. Needles, rarely cleaned between injections, spread blood-borne diseases, and men with bodies covered in sores and abscesses became a common sight in the dens of Shanghai.

World History

World History