The Lives of the Irish Saints are written in Latin and in early medieval Irish. The latter are of special interest in that they seem to utilize local oral tradition in order to elucidate and illuminate their subject. Many miracles are attributed to the early Irish saints, and powers which vied with those of the druids in magic and cunning. For example, the druids were accredited with the ability to transform themselves, or others, into the form of certain animals; the saints on occasion manifest similar powers. At times natural phenomena obeyed the dictates of the druids - winds, fires, mists yielded to their commands. The same magical powers were brought into play by their saintly successors. Many such miracles are associated with the late sixth-century Irish saint Mochuda, who had his religious foundation at Rahan, County Offaly. The following example comes from his Irish Life, or Betha:

On a certain day in early springtime there came to tempt him a Druid {draoi), who said to him ‘In the name of your God cause this apple-tree branch to produce foliage.’ Mochuda knew that it was in contempt of the divine power the Druid proposed this, and the branch put forth leaves on the Instant. The Druid demanded ‘In the name of your God put blossom on it.’ Mochuda made the sign of the Cross over the branch and it blossomed presently. The Druid persisted ‘What profits blossom without fruit?’ For the third time Mochuda blessed the branch, and the fruit, fully ripe, fell to the earth. The Druid picked up an apple off the ground and, examining it, he understood it was quite sour, whereupon he objected. ‘Such miracles as these are worthless, since the fruit is left uneatable.’ Mochuda blessed the apples, and they became as sweet as honey. And in punishment for his opposition the Druid was deprived of his eyesight for a year. He went away, and at the end of the year he came back to Mochuda and did penance, whereupon he received his sight back again, and he returned home rejoicing.

(Power 1914: 93)

The choice of an apple branch with which to test the magical powers of the saint was not random. The apple tree, according to the native tradition, grew prolifically in the Celtic Otherworld, putting forth leaves, blossom and fruit without cessation. In the story of Cormac's Adventures in the Land of Promise (translated in Dunn

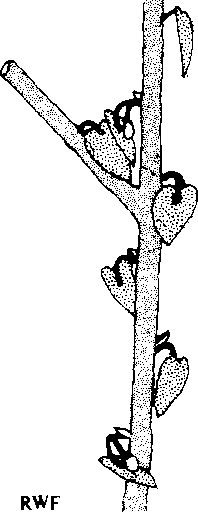

1969: 503ff.) a stranger approaches the king of Tara, County Meath, who is looking out over the countryside at dawn. The season is Beltain, May, a time of magic. Later the king learns that his visitor is the god Manannan, an important deity in the Insular Celtic world. He carries on his shoulder a silver branch on which there are three apples of gold. ‘Delight and amusement enough was it to listen to the music made by the branch.’ A similar story is told in the tale The Adventures of Connla the Tair. Connla, son of Conn, high-king of Ireland, was with his father at the druidic centre Uisnech, in modern County Westmeath, ancient centre of all Ireland. A beautiful young woman approached him, invisible to all except Connla. She was a goddess from the Otherworld. Although she could not be seen, her voice could be heard. ‘Whereupon the Druid (Corann) sang a magic incantation against the voice of the woman, so that no one could hear her voice.’ But before the young woman departed ‘before the potent chanting of the Druid’, she threw an apple to the boy. He lived on the flesh of that apple alone for a whole month. ‘What he ate of the apple never diminished it, but it remained always unconsumed’ (Dunn 1969: 489). These are but two examples of the occurrence in early Irish of magical apples, and their connection with a god or a druid or both. In his choice of the apple branch in order to work his spells against Mochuda, the druid must have felt himself to be on fairly safe ground; his dismay at the superior magic of his enemy must have been considerable. Here, at the very beginning of our Investigation, we witness a scene which would doubtless have been familiar to a much earlier Celtic world (Figure 23.1).

The passage from the Life of Saint Mochuda is of especial interest in that it demonstrates the survival of an active paganism in Ireland in the late sixth century, some one and a half centuries after the Patrician mission, and several centuries after Tiberius issued a decree against the druids and learned classes in Gaul in the first century AD. Even at this late date Irish druldism offered an alternative-belief-system. While the origins of druidlsm and the earliest religious rites of the druids remain obscure, the survival of druidic Influence and the continuing role in some form of the druid immediately after the introduction of Christianity in Ireland Is not in question. Druids figure in early Irish hagiographies, in certain of the Penltentials, and in prayers for protection known as loricae (Bieler 1953; Mac Eoin 1962; O’Lochlainn 1961). The constant druidic presence in the orally transmitted sagas demonstrates the original integral role of this order in pagan Irish society; and the huge corpus of native learning and tradition was dependent in its written form upon the early churchmen, who tried to record it as faithfully as possible.

The complex laws of medieval Ireland likewise testify to the continuing presence In some form of the druids and druidic beliefs, until the eighth century. At the same time, their elevated place In society would seem to have been usurped by the filid, the vdtis of Gaul, the scholarly poets with certain original powers of a priestly and prophetic nature. These powers were shared by another class of learned men stemming from the pre-Ghristlan druidic order, the so-called brehons (from Old Irish brithemain, ‘judges’). In these two learned orders a great deal of the ancient teachings of the druids must have survived. Later still, the blacksmith In Geltic society, with his alleged powers of healing, his spells, and his mastery of iron, the magical metal, and the itinerant soothsayers replaced the influence of the old learned orders to some extent. For example, this is reflected In the great corpus of spells.

Figure 23.1 Part of the cult tree, 2 ft in (70 cm) high, of wood, bronze and gold leaf, found in 1984 in Manching, Bavaria, on a wooden platter plated with richly decorated gold plating.

(V. Kruta et al. (eds) The Celts, London 1991: 530-1.)

Prayers for protection, incantations and charms in Scottish Gaelic current until early in the twentieth century and known as Carmina Gadelica, as collected and recorded by Alexander Carmichael. This remarkable compilation of material from the rich oral tradition of Gaelic Scotland further testifies to the longevity of the ancient beliefs which were once under the aegis of the druidic orders.

Tradition preserved in the hagiographies, in sagas and poems and early historical tales, reveals unequivocally the high status of the pre-Christian druids of Ireland which equalled that enjoyed by the druids in Britain and on the Continent, according to the classics. In addition to the pre-eminent priestly functions, the druid deployed magical powers, as attested by his incantations, and the ability to foresee the future and to predict the outcome of events. His knowledge of astrology must have been considerable, as was his skdl in calendncal computation. He was believed to have powers of shape-shifting, and to be able to change the shapes of others, turning humans into animals or birds at will. Thus he must have been a master of illusion. He was also a skilled healer, with a wide knowledge of the therapeutic properties of herbs and substances. Most importantly, perhaps, he was a teacher of the sons of noblemen, guardian of the hereditary learning and oral tradition.

By the time the Irish law books were compiled in the seventh and eighth centuries the druid still had a place in the legal codices, but under the increasing influence of Christianity he had come to be regarded as a sort of witch-doctor or sorcerer. But while he was discriminated against in the medieval Irish laws, he was not ignored. An impressive example of this discrimination occurs in the Old Irish law text entitled Bretha Crolige (Kelly 1988:60). The druid, together with the satirist (cdinte) and the brigand {diberg) is entitled to sick-maintenance (othrus) only at the level of the boaire, ‘cow-noble, owner of stock’, ‘no matter how great his rank, privilege or other rights’ (ibid.). He did, however, still have sufficient influence to be included among the doernemeds, dependent or privileged people, of the legal tract known as Uraicecht Becc, ‘Small Primer’. The druids then had a definite if elusive role in Irish society at this period. Just as the satirist’s words were feared, so were the spells of the druids a continuing source of unease. The druids still seem to have practised sorcery, adopting a position reminiscent of a crane’s, standing on one leg with one arm outstretched and one eye closed. This was called corrguinecht, which may mean something like ‘crane-wounding’ (ibid.). The crane played a sinister role in Celtic mythology and religion.

This mode of sorcery seems to have included the chanting of a satire. An eighth-century hymn asks for God’s protection against the spells of women and blacksmiths and druids. This same word for spells - brichtu is used on the Chamalieres tablet in the form bricti.

It also seems likely that the druids continued to concoct love-potions, which are referred to In legal texts. In the early Irish saga Serglige Con Culainn, ‘The Wasting Sickness of Cu Chulainn’, the druids come to the assistance of the hero Cu Chulainn and his mistress the goddess Fand by giving them draughts of a potion which would make them totally forget their passion. Then the god Manannan, Fand’s husband, ‘shook his cloak between them so that they might never meet together again throughout eternity’ (Dunn 1969: 198).

The undoubted magical powers of the druids could also be employed in war. The classics tell us that this was the case In Gaul. Diodorus Siculus, writing In the late first century BC, says that druids and chanting bards would come between armies lined up for battle, charming them and so averting combat (Kendrick 1927: 83). The Annals of Ulster of 561 note the use of a druid fence {erbe ndruad) in the battle of Cull Dremne. Any warrior leaping over it was killed. Druids could also ensure victory in battle for the weaker side, according to the law Bretha Nemed toi'sech. This states: ‘a defeat against odds... and setting territories at war confer status on a Druid’ (Kelly 1988:61) (Figure 23.2).

World History

World History