The beginning of the New Kingdom presented challenges of every type to the new Ahmosid dynastic family following the expulsion of the Hyksos. Probably among the more pleasant demands on the kings was the revival of temples installed with statues of Ahmose, Amenhotep I, and Thutmose I. At the beginning of any new era large-scale art production surely strained the resources of trained artisans to carry out the work, and the early Eighteenth Dynasty was likely no exception. The limited remains from the reign of Ahmose indicate that his efforts were significant in Abydos and Karnak where artisan workshops existed already, but elsewhere production appears to have been of inconsistent style and quality. For example, Vivian Davies observed that statues of Ahmose and Amenhotep I dedicated on Sai Island in northern Sudan were likely the work of local artisans betraying Nubian stylistic preference. (Davies 2004) At the Buhen Temple the king’s additions were added in crudely incised relief, suggesting an absence of highly trained Egyptian craftsmen. Edna Russmann recently pointed out that Ahmose’s style at Abydos differed from that at Karnak due to the archaistic tendency at the latter temple, where the early Twelfth Dynasty style remained the standard model (Russmann 2005). At Abydos Ahmose’s monuments owed more to the late Second Intermediate Period, whose style was visible on the numerous stelae produced there during that era. Yet, the fragments of Ahmose’s relief, as retrieved by Stephen Harvey, suggest that the Abydos monuments required a crew of artisans with a high level of training, and it is possible that the existing craftsmen were supplemented by others (Harvey 2004).

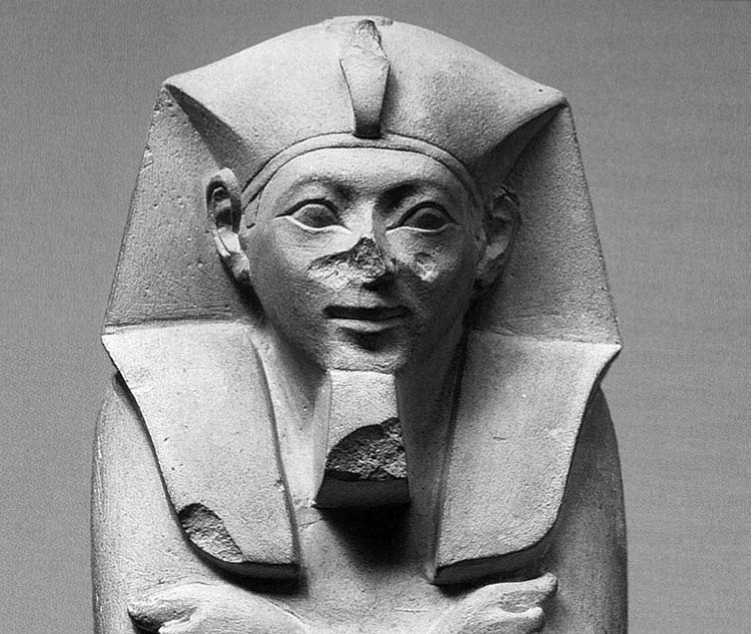

Ahmose’s face from a limestone life-sized statue with the white crown (private collection) has extremely large very slightly oblique bulging eyes set in a broad rounded face (Romano 1976). The brows are plastic and highly stylized. The damaged mouth is clearly smiling and not ungenerous. The face on a shabti (British Museum EA 32191; figure 40.1) is more heart-shaped, but the finely incised features are similar, and the mouth is carefully defined with the shape seen on later Thutmosid faces. Russmann identified the origins of the highly idealized Thutmosid style in the shabti face of Ahmose and in some of the non-royal Theban statues from the late Seventeenth and early Eighteenth Dynasties, and she noted their correspondence with royal and nonroyal Theban coffins of the same era. (Russmann 2005) Yet, as she also commented, other styles surfaced during this period until the Thutmosid type was well developed, perhaps by the reign of Thutmose II, but certainly in that of Hatshepsut. Alongside the delicate idealized face of Amenhotep I on his Karnak reliefs, an individualizing style

Figure 40.1 Shabti of Ahmose. Limestone. British Museum EA 32191. Courtesy Trustees of the British Museum.

Depicting Amenhotep I appeared in his Osirid statuary from Deir el-Bahri, where a large and fleshy nose protruded from a heavy face with a thin horizontal mouth (British Museum EA 683). The Osirid type may have offered a nod toward Mentuhotep II’s Deir el-Bahri sculptures, yet faces on earlier rishi coffins and late Seventeenth Dynasty royal coffins, such as the gilded one of Queen Ahhotep (CG 28501), may have been another source of the alternative facial type (Roth 2002). Those features were more summary, but the broad prognathous facial shapes, large noses, and thin mouths are very evocative of the more carefully modeled features of Amenhotep I. The colossal statues ofThutmose I came close to the Thutmosid idealized facial type and wander far from the Deir el-Bahri faces of Amenhotep I. Thutmose I has a long nose that broadens at the its base with a thicker and broader mouth than his predecessor - whether in statuary or relief - and is slightly smiling. The eyes are naturally arched and very wide open, as seen on the one well preserved example, CG 42051 (Bryan 2002; Russmann 2005; figure 40.2). The breadth of the face beneath the eyes is similar to the Ahmose statues but with the more prominent cheek bones so typical of the Thutmosid faces. The statues of Thutmose II are either fragmentary or dedicated by Hatshepsut and cannot be properly evaluated for distinctive features (Dreyer 1984), yet by the time of Hatshepsut’s regency the tentative elements of portrayal had given way to a strongly

Figure 40.2 Facial detail from an Osiride of Thutmose I. Sandstone. Temple of Karnak. CG 42051. Courtesy Supreme Council of Antiquities.

Identifiable model that was only subtly tweaked during her kingship and that of Thutmose III up to the reign of Thutmose IV.

Russmann pointed to new royal facial features and additional statue poses and attributes for female images as innovations of the early New Kingdom (Russmann 2005). The relationship between faces on funerary statues and coffins may have resulted from the deployment of readily available artisans from Western Thebes to work on a broad range of monuments, perhaps crossing artistic forms as a result. For example, female figures shown with the left leg advanced were not uncommon in two dimensional representations of the late Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period, but, other than as wooden statuettes (CG 495 and 797) (Borchardt 1930), were not commonly produced in statuary until the beginning of Dynasty Eighteen. The artisans of such wooden funerary statuettes may have been well positioned to craft these early New Kingdom striding sculptures. As Russmann noted, however, the new poses suited the newly expanded visibility of women in Egyptian elite culture and soon were made in every size and material.

During the reigns of Ahmose, Amenhotep I, and Thutmose I and II, the following royal statue types are attested: seated wearing white crown and Sed-festival robe: Ahmose, Amenhotep I, and Thutmose II (inscription posthumous); Osirid: Amenhotep I, Thutmose I; seated wearing the nemes: Thutmose I (fragmentary); Thutmose II (fragmentary); group with deities: Thutmose I (upper half restored post-Amarna); kneeling: Thutmose II (inscribed and attributed). Sphinxes (one with human hands) are attributed to Amenhotep I. This brief list of statue types is almost certainly under-representative, since Hatshepsut and Thutmose III dismantled and altered so many early Eighteenth Dynasty monuments at Karnak and Deir el-Bahri. The life-sized examples from Egypt and Nubia (Ahmose, Amenhotep I, Thutmose II) depict the king in the most ancient royal portrait type - that of the king in jubilee or coronation robe wearing the white crown (Davies 2004; Dreyer 1984). This combination, seen also on the Second Intermediate period Karnak statue of Merhotepre Sobekhotep (Davies 1981), recalls the Nekhen statues of Khasekhem that underlined his Upper Egyptian association. Perhaps, then, not only the divine legitimation of the ruler but perhaps also his domination over the southern regions was implied in the placement at Elephantine and Sai Island of the early New Kingdom statues. The Osirid statues of Amenhotep I and Thutmose I are very different in form and size, but the architectural use of all the examples was fundamental. In adorning the mud-brick works at Deir el-Bahri, Amenhotep I used statues attached to broad pillars, while Thutmose I added his thirty-six colossal images in the Hall behind the Fourth Pylon and created a peristyle court with them (Lindblad 1984). Both rulers emphasized their association with the great god Osiris by means of these mummiform statues, but Amenhotep I’s representation in the double crown combined the power of the dual king with the image. At Karnak Thutmose I may have been shown in the red crown as well as the white, like Senwosret I on his Osirids from Lisht (CG 399 and 401), but at Karnak the focus on veneration of deceased kings would have underlain the use of the statue type. The other statue types are so poorly attested as to provide little to our understanding of their use, but there are no new forms among them. Rather it is in the non-royal sculpture that indications of new demands on the role of statuary are evident. As Russmann noted, elite females played a more active role after the late Second Intermediate Period. (Russmann 2005) On the so-called ‘‘Donation Stela’’ of Ahmose from Karnak Queen Ahmose-Nefertari is shown striding behind her husband, clearly an active participant in the scene. Although no known temple statue illustrates this pose in the early Eighteenth Dynasty, small non-royal funerary sculptures did so, and by the reign of Amenhotep III had become a statue type used for large-scale images of queen and elites alike (Bryan 2008). The inclusion of hand-held attributes, such as lotuses, may also have been an early signal of the increased communicativeness of sculpture seen so plainly in the statuary of Hatshepsut and her contemporaries.

World History

World History