English, divided by the Wars of the Roses, were driven out of France, keeping only Calais. The same year saw the Turks taking Constantinople, which provoked consternation, agitation and excitement in the whole Christian world.

In that siege and seizure of the capital of the Eastern Roman empire, cannon and gunpowder achieved spectacular success. To breach the city walls, the Turks utilized heavy cannons which, if we believe the chronicler Critobulos of Imbros, shot projectiles weighing about 500 kg. Even if this is exaggerated, big cannons certainly did exist by that time and were more common in the East than in the West, doubtless because the mighty potentates of the East could better aflford them. Such monsters included the Ghent bombard, called “Dulle Griet”; the large cannon “Mons Berg” which is today in Edinburgh; and the Great Gun of Mohammed II, exhibited today in London. The latter, cast in 1464 by Sultan Munir Ali, weighed 18 tons and could shoot a 300 kg stone ball to a range of one kilometer.

A certain number of technical improvements took place in the 15th century. One major step was the amelioration of powder quality. Invented about 1425, corned powder involved mixing saltpeter, charcoal and sulphur into a soggy paste, then sieving and drying it, so that each individual grain or corn contained the same and correct proportion of ingredients. The process obviated the need for mixing in the field. It also resulted in more efficient combustion, thus improving safety, power, range and accuracy.

Another important step was the development of foundries, allowing cannons to be cast in one piece in iron and bronze (copper alloyed with tin). In spite of its expense, casting was the best method to produce practical and resilient weapons with lighter weight and higher muzzle velocity. In about 1460, guns were fitted with trunnions. These were cast on both sides of the barrel and made sufficiently strong to carry the weight and bear the shock of discharge, and permit the piece to rest on a twowheeled wooden carriage. Trunnions and wheeled mounting not only made for easier transportation and better maneuverability but also allowed the gunners to raise and lower the barrels of their pieces.

One major improvement was the introduction in about 1418 of a very efficient projectile: the solid iron shot. Coming into use gradually, the solid iron cannonball could destroy medieval crenellation, ram castle-gates, and collapse towers and masonry walls. It broke through roofs, made its way through several stories and crushed to pieces all it fell upon. One single well-aimed projectile could mow down a whole row of soldiers or cut down a splendid armored knight.

About 1460, mortars were invented. A mortar is a specific kind of gun whose projectile is shot with a high, curved trajectory, between 45® and 75®, called plunging fire. Allowing gunners to lob projectiles over high walls and reach concealed objectives or targets protected behind fortifications, mortars were particularly useful in sieges. In the Middle Ages they were characterized by a short and fat bore and two big trunnions. They rested on massive timber-framed carriages without wheels, which helped them withstand the shock of firing; the recoil force was passed directly to the ground by means of the carriage. Owing to such ameliorations, artillery progressively gained dominance, particularly in siege warfare.

Individual guns, essentially scaled down artillery pieces fitted with handles for the firer, appeared after the middle of the 14th century. Various models of portable small arms were developed, such as the clopi or scopette, bombardelle, baton-de-feu, handgun, and firestick, to mention just a few.

In purely military terms, these early handguns were more of a hindrance than an asset on the battlefield, for they were expensive to produce, inaccurate, heavy, and time-consuming to load; during loading the firer was virtually defenseless. However, even as rudimentary weapons with poor range, they were effective in their way, as much for attackers as for soldiers defending a fortress.

The harquebus was a portable gun fitted with a hook that absorbed the recoil force when firing from a battlement. It was generally operated by two men, one aiming and the other igniting the propelling charge. This weapon evolved in the Renaissance to become the matchlock-musket in which the fire mechanism consisted of a pivoting S-shaped arm. The upper part of the arm gripped a length of rope impregnated with a combustible substance and kept alight at one end, called the match. The lower end of the arm served as a trigger: When pressed it brought the glowing tip of the match into contact with a small quantity of gunpowder, which lay in a horizontal pan fixed beneath a small vent in the side of the barrel at its breech. When this priming ignited, its flash passed through the vent and ignited the main charge in the barrel, expelling the spherical lead bullet.

The wheel lock pistol was a small harquebus taking its name from the city Pistoia in Tuscany where the weapon was first built in the 15th century. The wheel lock system, working on the principle of a modern cigarette lighter, was reliable and easy to handle, especially for a combatant on horseback. But its mechanism was complicated and therefore expensive, and so its use was reserved for wealthy civilian hunters, rich soldiers and certain mounted troops.

Portable cannons, handguns, harquebuses and pistols were muzzle-loading and shot projectiles that could easily penetrate any armor. Because of the power of firearms, traditional Middle Age weaponry become obsolete; gradually, lances, shields and armor for both men and horses were abandoned.

The destructive power of gunpowder allowed the use of mines in siege warfare. The role of artillery and small firearms become progressively larger; the new weapons changed the nature of naval and siege warfare and transformed the physiognomy of the battlefield. This change was not a sudden revolution, however, but a slow process. Many years elapsed before firearms became widespread, and many traditional medieval weapons were still used in the 16th century.

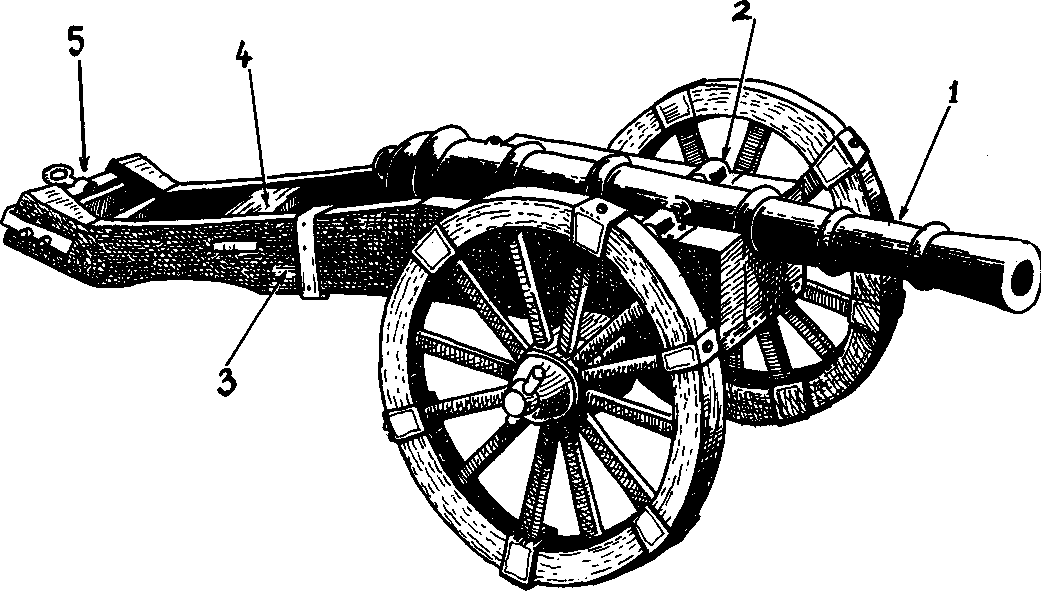

View of a gun. A piece of artillery is composed of two main parts. The gun (1) is fitted with trunnions (2) allowing it to be fixed firmly on a strong timber carriage composed of two cheeks (3) linked by cross-bars (4), fitted with a cross (5) and a hook, and two heavy wheels with axle-tree for transport. This kind of field gun did not undergo major change until the second half of the 19th century.

One factor militating against artillery’s advancement in the 15th century was the amount of expensive material necessary to equip an army. Cannons and powder were very costly items and also demanded a retinue of expensive attendant specialists for design, transport and operation. Consequently firearms had to be produced in peacetime, and since the Middle Ages

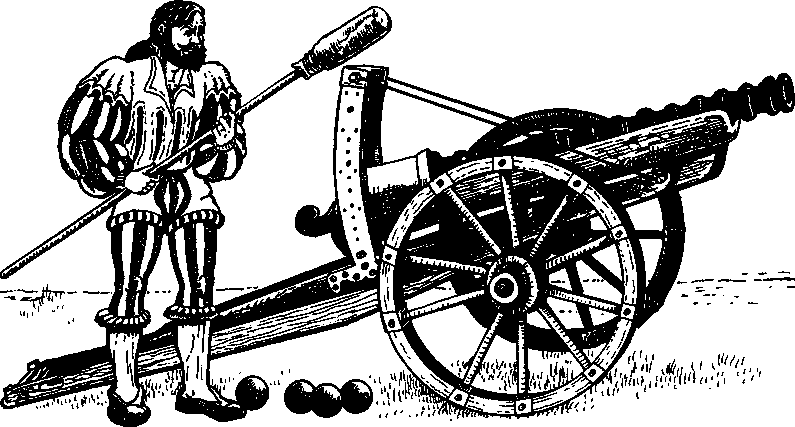

Italian culverin. Dating from the latter half of the 15th century, this gun displayed an interesting mounting, complete with a system of regulating elevation.

World History

World History