Concessionary companies were an important component of economic development in much of colonial Africa, particularly during the early consolidation phase from 1885 to 1920. Most typically, these were private European businesses lured to make investments of capital and manpower in Africa in return for a grant (or concession) of land, over which it gained privileged rights of exploitation. While specific features varied from colony to colony, as well as over time, the widespread use of this policy highlights two crucial features of African colonialism. First, it reflects the prevailing philosophy that economic development should be led by private enterprise, much as it had been done in European history. As a consequence, most colonial administrations lacked the financial resources and the personnel to undertake development alone. Second, the concessionary policy embodied a pervasively negative European perception of Africans and their culture. The promotion of European enterprise in Africa was in part based on the belief that Africans were too backward and lazy to make a meaningful contribution beyond the role of common laborer. Together, these constraints and beliefs forged a colonial policy that favored European interests over those of Africans, and helped to lay the foundations for African economic underdevelopment.

The concessionary policy in colonial Africa evolved out of the European tradition of chartered companies, which had successfully enlarged imperial possessions and trade in Asia and North America in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. When Europeans became interested in Africa in the mid-nineteenth century, private companies again expanded the territorial and commercial domain of European powers. The United African Company (later renamed the Royal Niger Company), the Imperial British East Africa Company, and Cecil Rhodes’s British South Africa Company, for example, secured for Britain future colonies in eastern, western, and southern Africa. Following the partition of Africa at the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, concessionary companies played a crucial role in consolidating European rule. In many colonies, companies took the lead in expanding Western influence, improving transportation, and introducing Africans to export-commodity production. To attract private investment, colonial administrations commonly offered large land concessions and varying amounts of administrative power. A general exception was found in the colonies of West Africa, where a longer tradition of European-African trade encouraged the colonists to rely more heavily on African household production.

From 1885 to 1920 in some areas of colonial Africa, concessionary companies dwarfed all other forms of economic activity. In King Leopold’s Congo Free State, one large mining consortium, the Katanga Company, gained administrative and commercial control over a huge tract covering more than 100 million acres. In the neighboring French Congo, forty companies were granted concessions totaling nearly 70 per cent of the entire colony. Additional huge portions of equatorial forest were ceded to businesses interested in the ivory and rubber trade. In return, colonial administrations frequently took a substantial share of the profits, as well as company commitments for investments in railways and other expensive projects. As a result, the success and well-being of many colonial governments became firmly intertwined with company profits, resulting in a close collusion of interests, policies, and personnel.

The early reign of concessionary companies was generally abusive, unprofitable, and ultimately untenable. Granted sweeping administrative powers, private companies ruled their territories absolutely, erecting economies oriented toward short-term profits over long-term investment. In the forest regions of central Africa, the rubber and ivory trade quickly degenerated into a brutal and violent system. Company agents and administrative personnel were typically rewarded or promoted in proportion to the amount of exportable commodities produced in their territories, resulting in widespread atrocities and a reign of terror. African workers who failed to meet their ever-increasing quotas of rubber or ivory were beaten, whipped, and tortured. In some regions, forced labor dramatically undermined normal subsistence activities, causing famine, illness, and early death. But such wholesale exploitation of people and resources ultimately proved counterproductive. African armed resistance required costly military interventions and diminished production, causing several companies to declare bankruptcy. Excessive harvesting of rubber and ivory also destroyed natural resources, causing a steady decline in production and profits by 1900. Finally, when missionary reports of the atrocities reached Europe, an outraged public demanded reform. In the most dramatic case, King Leopold was forced to cede his Congo Free State to Belgium in 1908.

By 1920, the concessionary policy in much of colonial Africa was significantly reduced or revised. European private enterprise was still widely encouraged, but under stricter supervision and tighter control. An illustrative example is seen in the Belgian Congo’s agreement with Lever Brothers, the British soapmaker. In 1919, the company received five concessionary zones (much smaller than those awarded earlier by the Congo Free State), in which to establish palm plantations and processing facilities. In addition, Lever Brothers was required to improve and invest in the welfare of its workers by instituting labor contracts and by building schools and clinics. In the Belgian Congo, as in other colonies, such reforms were heralded as promoting long-term economic development for the benefit of Europeans and Africans alike. But in reality, the basic Eurocentric structure and orientation of the colonial economy remain unchanged. While the concessions were smaller, they were often more numerous, resulting in even greater European control of the economy. Company investments in African welfare were generally minimal and rarely enforced. Instead, the state actively ensured the success of private European capital, enacting taxation and other policies to create a large, compliant, and cheap labor force. To protect company interests, African economic competition was stifled or prohibited, under the pretext that such production would yield inferior quality exports. Lacking viable alternatives, African participation in the colonial economy remained largely limited to the role of unskilled laborer. Despite the reforms, the enduring concessionary policy shows that European profits and interests remained preeminent over African needs and concerns.

Colonial concessionary companies have left a lasting legacy to postcolonial Africa. At independence, African governments inherited economies dominated by European capital and oriented toward European markets. Prohibitions placed on African competition had successfully hindered the rise of an African entrepreneurial class, which might have served as the catalyst for new economic growth and opportunities. Instead, the vast majority of the population remained underskilled and underfinanced. In some former colonies, the lingering economic power of European companies has promoted neocolonialism, whereby

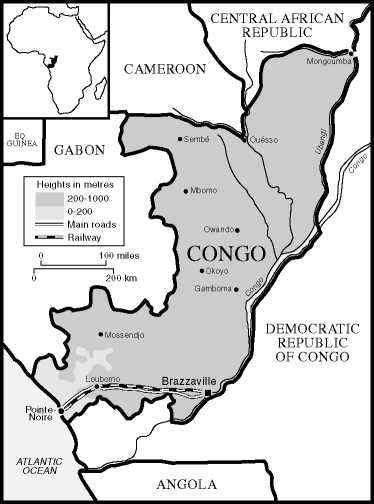

Congo.

Foreign interests have exerted considerable influence over the policy decisions of African leaders, often at the expense of its citizens. Moreover, lacking the capital and resources to restructure their economies, many African nations have been forced to maintain the same cash crop, export-oriented economies created by the concessionary companies, reinforcing a continuous cycle of underdevelopment that has proved exceedingly difficult to overcome.

Samuel Nelson

See also: Colonial European Administrations: Comparative Survey; Colonialism: Impact on African Societies.

Further Reading

Boahen, A. Adu (ed.). Africa under Colonial Domination, 1880-1935. London: John Curry, 1990.

Coquery-Vidrovitch, C. Le Congo au temps des grandes com-pagnies concessionnaires, 1898-1930. Paris: Mouton, 1972.

Depelchin, J. From the Congo Free State to Zaire: How Belgium Privatized the Economy. A History of Belgian Stock Companies in Congo-Zaire from 1885 to 1974. Oxford: Codresria, 1992.

Duignan, P., and L. H. Gann (eds.). Colonialism in Africa, 1870-1960, vol. 4, The Economics of Colonialism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975.

Fieldhouse, D. K. Unilever Overseas: The Anatomy of a Multinational, 1895-1965. London: Croom Helm/Stanford, Calif.: Hoover Institute Press, 1978.

Harms, R. “The World ABIR Made: The Maringa-Lopari Basin, 1885-1903.” African Economic History, no. 22 (1983): 125-139.

Hopkins, A. G. An Economic History of West Africa. New York: Columbia University Press, 1973.

Nelson, S. Colonialism in the Congo Basin, 1880-1940. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Center for International Studies, 1994.

Confederation: See South Africa: Confederation, Disarmament, and the First Anglo-Boer War, 1871-1881.

World History

World History

![The General Who Never Lost a Battle [History of the Second World War 29]](/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432581983_1425486253_part-29.jpeg)