Nineteenth Century

Nineteenth-century Mauritania remained a stateless society dominated by nomadic and semisedentary Arabo-Berber pastoralists (Moors), with Black Wolof and Tukolor sedentary cultivator communities located primarily along the Senegal River. Enslaved blacks and descendants of freed slaves bound by clientage to their former masters existed throughout Mauritanian society.

A process of cultural and linguistic Arabization among the Muslim Moors that had begun in the sixteenth century with the first influxes of small groups of Arab immigrants culminated in the nineteenth century. By the end of the century, the Berber Znaga dialect had largely given way to the Arabic dialect known as Hassaniyya, and patrilineal Arab genealogies had largely supplanted older matrilineal Berber genealogies as the basis for constructing social identity.

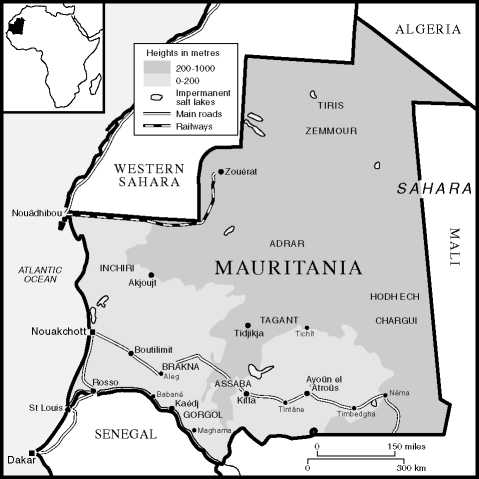

Mauritania.

Important sources from that period suggest a rigid social stratification dominated by Arab warriors called the Banu Hassan and Berber clerics known as the Zawaya. In fact, social identity, both genealogically and occupationally, was considerably more fluid. Groups periodically merged, disbanded or emigrated, acquiring or shedding aspects of their identity in the process. Similarly, groups once engaged in nomadic pastoralism occasionally became sedentary in the transition into trade or scholarly activity, while others adapted to a new pastoralist culture after moving from regions that supported camel husbandry to regions that were better suited to cattle. Warriors who based their livelihood on raiding and the collection of protection tribute were sometimes forced into tributary status themselves by more powerful groups, and in some cases relinquished their arms altogether under threat of punishment or under the influence of religious leaders. At other times, groups whose leaders were revered spiritual figures had recourse to take up arms against one another, as occurred between the Kunta and the Tajakant on numerous occasions throughout the century.

The gum arabic trade, transacted at trading ports established on the Senegal River’s right bank in the southwestern Mauritanian region known as the Gibla, spurred growing European interest in Mauritania throughout the nineteenth century. Europeans used gum arabic, a resin found in the variety of acacia tree prevalent across southern Mauritania, in the production of textiles and pharmaceuticals. Banu Hassan groups initially dominated trade at the ports and required toll payments by Moorish and French traders (or their indigenous representatives) alike. A growing French military presence in Senegal gradually eroded Hassani authority, first by granting French protection to, then by establishing French authority over, agricultural communities formerly under Banu Hassan hegemony on both banks of the Senegal River. By mid-century, the governor of Senegal Louis Faidherbe was able to exact Hassani recognition of French sovereignty even over the right bank ports.

In 1899 the French colonial ministry successfully lobbied to expand French authority throughout West Africa, including Mauritania. Responding to a request by France’s prime minister for a means of achieving this goal at minimal cost in men or materiel, an Algerian-born Corsican in the colonial administration named Xavier Coppolani proposed a method of “peaceful pacification” that was quickly embraced in the foreign office. Coppolani’s plan entailed coopting Moorish religious leaders through promises of protection from the region’s endemic raiding, thereby removing the major obstacle to their religious and commercial endeavors. Early on, Coppolani succeeded in gaining the cooperation of the most influential religious figures in the Gibla, Shaykhs Sidiyya Baba and Sa’d Bu.

Coppolani also attempted to play on rivalries among warrior groups in his efforts to gain a foothold in the region, although early success with this divide and conquer strategy proved ephemeral. Faced with stiffening resistance, Coppolani’s initial strategy quickly gave way to overtly military means of conquest. Moors opposed to the growing French presence turned to Sa’d Bu’s brother Ma’ al-’Aynayn whose close relations with the Moroccan sultan and outspoken opposition to any foreign incursion drew the growing resistance movement to him. The French attributed Coppolani’s assassination in 1905 to Ma’ al-’Aynayn’s machinations though largely on circumstantial evidence. From his compound at Smara, Ma’ al-’Aynayn led the struggle to force the French out, until 1909 when he and his followers were driven from Smara in the face of an advancing French force and were forced to flee to Tiznit in southern Morocco.

The French government incorporated Mauritania into its wider colonial administration of Afrique Occidental Franpaise (AOF). Organized to mirror other AOF civil territories, France divided Mauritania into administrative units known as cercles that remained largely intact even beyond independence. Mauritania was proclaimed a separate colony in 1920, although still under the auspices of the AOF’s governor general. Notwithstanding these administrative changes, French “pacification” of the whole of Mauritania would not be complete until 1934. Even then, many of the colony’s nomadic inhabitants remained either beyond the pale of French rule or subject to only nominal government control. In 1944 a decision to add the eastern region known as the Hodh to Mauritania from the adjoining territory the Soudan (modern Mali), created the borders that exist today.

Following the end of World War II, France responded to growing criticism both at home and abroad of its continued role as colonizer by initiating steps to grant its colonial subjects greater autonomy. In accordance with the 1946 constitution of the Fourth Republic, Mauritania formally became part of the French Union as an overseas territory. The election of Mauritania’s first representative to the French National Assembly in 1946 underscored considerable political divisions among Mauritanians. The more progressive elements were predominantly socialist, avowedly nationalistic, and hostile to the region’s traditional chieftaincies, while more conservative elements drawn primarily from the traditional power structure sought to maintain the status quo including retaining close ties with France. The progressives, with the backing of the French Socialist Party, carried the day, electing the young nationalist and political neophyte Horma Wuld Babana.

Wuld Babana ultimately alienated his core constituencies by remaining in Paris throughout his tenure as representative in order to pursue his own personal political ambitions, and when he launched a new political party in 1948, the Entente Mauritanienne, it failed to secure a solid base in Mauritania’s developing political arena. A rival party formed that same year with the backing of the traditional chieftains, the Union Progressiste Mauritanienne (UPM), filled the political vacuum; its candidate, Sidi al-Mukhtar N’Diaye, succeeded in unseating Wuld Babana in his 1951 reelection bid. Wuld Babana remained a controversial figure on the Mauritanian political scene for several more years, but his support of Moroccan claims of a Greater Morocco that included Mauritania finally doomed his political future.

The following year the UPM won all but two of the twenty-four seats in the General Council, which France had established as a consultative body and a first stage in granting greater future legislative autonomy to the territory. Not long after its formation, leadership of the UPM passed to Mukhtar Wuld Daddah, a member of Sidiyya Baba’s important Gibla tribe the Awlad Ibiri. Wuld Daddah attended school in Saint Louis, Senegal, before serving the colonial administration as an interpreter during World War II. After the war, he studied in France where he attained a law degree, becoming the first Mauritanian trained in French law. Despite the UPM’s continued success under Wuld Daddah’s guidance, the party failed to represent all segments of Mauritanian society’s interests.

In the mid-1950s, a generational divide among party members resulted in the formation of the Association de la Jeunesse Mauritanienne (AJM) whose members were impatient with the older UPM leadership. The AJM sought to push harder for Mauritania’s independence and democratization, but its pan-Arab inclinations alienated many non-Moors. The Bloc Democratique du Gorgol (BDG) arose among Mauritania’s Halpulaar population largely in response to fears of closer ties with the Arab north, and in particular, of calls for political unity with newly independent Morocco. On the other end of the political spectrum, the Nahda al-Wataniyya al-Muritaniyya Party represented Moors in the north of the territory who sought a rapprochement with Morocco while opposing federation with Mali and Senegal.

In April 1957 the French government moved a step closer to granting its West African colonies independence by reorganizing the AOF into distinct governing councils. Wuld Daddah was selected to form a Mauritanian government, and in an effort to achieve national unity, he drew from opposition and allies alike to form a cabinet. In May 1958 Wuld Daddah formed a new party the Parti du Regroupement Mauritanien (PRM) that fused the UPM, remnants of Entente Mauritanienne, and moderates in the AJM. Nahda remained as the only opposition party capable of challenging the PRM until a corruption scandal and internal dissent destroyed its viability as a mainstream political force. In response to Nahda’s increasingly militant posture, Wuld Daddah’s government banned the party and arrested its leaders. This left the PRM unchallenged on the eve of Mauritanian independence.

France granted Mauritania autonomy as a member of the French Community in October 1958, and on March 2, 1959, the Islamic Republic of Mauritania adopted its first constitution. Over the course of the next eighteen months France transferred power to Wuld Daddah’s government culminating on November 28,1960, with a proclamation of Mauritanian independence.

Glen W. McLaughlin

Further Reading

Cleaveland, T. “Islam and the Construction of Social Identity in the Nineteenth Century Sahara.” Journal of African History. 39 (1998): 365-388.

Desire-Vuillemin, G. Histoire de la Mauritanie: Des origines a l’Independance. Paris: Editions Karthala, 1997.

Ould Cheikh, A. W. Elements d’histoire de la Mauritanie. Nouakchott: Centre Culturel Francais, 1988.

-. “Herders, Traders, and Clerics: The Impact of Trade,

Religion and Warfare on the Evolution of Moorish Society.” In Herders, Warriors, and Traders: Pastoralism in Africa, edited by J. G. Galaty and P. Bonter. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1991.

Taylor, R. M. “Warriors, Tributaries, Blood Money and Political Transformations in Nineteenth Century Mauritania.” Journal of African History. (1995): 419-441.

Webb, J. L. A., Jr. Desert Frontier: Ecological and Economic Change along the Western Sahel 1600-1850. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995.

World History

World History