The Sarajevo cri. sis was greeted in Berlin with conflicting counsels. Many Foreign Ministry-personnel, seeing a potential chain of disaster, took a more moderate line than the military. However, on 5 July the Kaiser, seconded by Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg, gave N'ienna a ‘blank cheque’ for action against Serbia. .As Szogyeny, the •Austro-Hungarian ambassador in Berlin, reported: ‘Action against Serbia should not be delayed. . . Even if it should come to a war between. Austria and Russia, we could be convinced that Germany would stand by our side. . .’ Germany would be sorry to see Austria miss ‘the present favourable moment' for strong measures.

Those who spoke thus in Berlin apparently felt that Austrian inaction, vaccillation, or delay would so reduce the prestige of the Dual Monarchy as to lead to severe repercussions, even the break up of the empire. The Kaiser himself was outraged at the shedding of royal blood, particularly that of the Archduke, a personal friend. He may hav-e thought that Tsar Nicholas, similarly indignant, would keep Russia aloof from the crisis. Nevertheless, at the beginning of July the Kaiser had commented, ‘The Serbs must be disposed of, and soon.’ The German historian Fritz Fischer has suggested that the actions of the German government in early July perhaps show that Germany was using Sarajevo as an excuse to launch a preventive war against Russia; but this interpretation is highly controv'ersial, and one can argue with equal success that Germany, feeling herself and Austria surrounded by hostility, saw Sarajevo as a fortunate chance to reassert her support for her ally. For even though. Austria was a partner of dubious strength, Germany wanted to keep her away from the Franco-Russian alliance system.

Many historians have argued that the Germans, either naively or disingenuously, thought that the approaching conflict might be confined to. Austria and Serbia. Russia, Berlin reasoned, might be in a position to do little more than bluff ineffectively, though her strength was growing daily. It was widely felt that Russian ambitions in the Balkans and elsewhere made war with Germany inevitable sooner or later. The question was: could Germany wait until the Russian colossus turned on her?

By 14 July Tisza had substantially agreed to Conrad’s arguments for a forward policy. Discussions in Vienna on 7 July showed that there was considerable fear on the part of Austria that if she did not now settle accounts with Serbia, German support in future was problematical. Some even feared a German-Russian settlement at. Austria’s expense. From Berlin Szogyeny emphasized that Russia was preparing for eventual war and, as the German Foreign Secretary, Jagow, reiterated, that in a few years Rus. sia would ‘overwhelm us if she is not forestalled’.

If. Austria allowed herself to become enmeshed in diplomatic negotiations over the assassinations, her enemies would have time to out-manocu re

Riie Austrian cavalry was an extras again cchool'a glorious past.

Her. Thus it was decided to send Serbia an extremely stiniv-worded memorandum. If, as Austria expected, Serbia were uncoo|)erative, an excuse for war would be provided. Despite Berlin’s impatience toward the leisurely pace of Austrian preparations against Serbia, it was decided to lull foreign suspicions by allowing the usual annual holidays to be taken: Moltke, tbe German Chief of Stalf, remained at Karlsbad until 25 July, and the Kaiser enjoyed his customary summer cruise.

'I'he.ustrians elected to delay their memorandum to. Serbia until the completion of the state

Visit to Russia of the I’rench President and Prime Minister, lest their presence in Saint Petersburg be used to stiffen the Russian position at the moment of crisis. On 22july. ])erhaps acting under the influence of the French, the Russians had warned. Austria not (o present Serbia with un-acce]rtable demands.

On 23 July the French state visit to Russia was completed. Immediately A'ienna sent a strong memorandum to the Serbs. I'he note contained ten demands; the most important rec|uired that Serbia allow. Austria to suppress local agitation against. Austria-Hungary and take action bersell

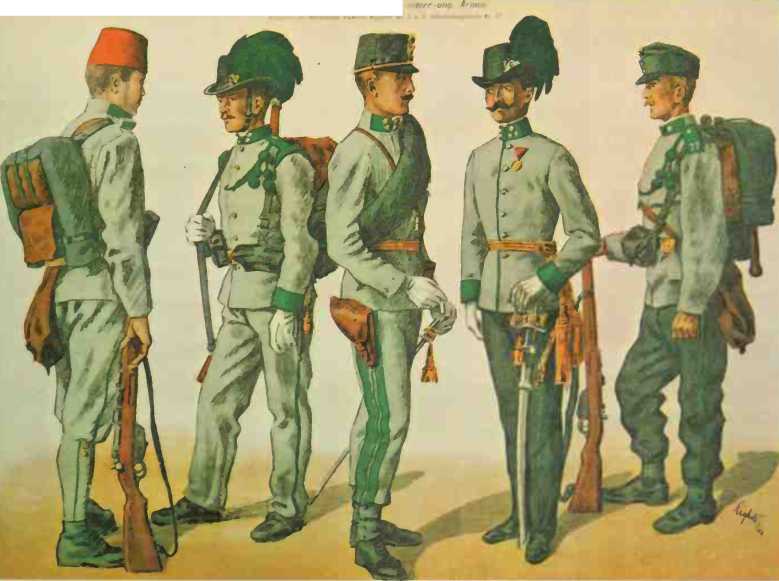

Jlfffu*rierungtn'oniftafefn der

.usirian army unilbrms were romanlir, ukI splendid.

Against those involved in the Sarajevo crime. Emperor Franz Josef said on reading the terms; ‘Russia cannot accept this. . . this means a general war.’ He spoke prophetically, but no one listened. Sazonov, the volatile Russian F'oreign Minister, echoed these sentiments when he learned of the contents of the Austrian note. The note was to be answered within forty-eight hours, although the Russians tried unsuccessfully to get the limit extended by another two days. But on 25 July, just before the time limit expired, Belgrade accepted most of the Austrian demands and offered to submit to arbitration those which infringed her sovereignty. Thus the Serbs had very cleverly put Vienna in the wrong by appearing in the guise of sweet reasonableness. As Lafore drily put it, ‘Butter remained visibly unmelted in their mouths.’ Yet they did not expect their reply to satisfy Vienna, for three hours before the reply was given, they had ordered mobilization.

Mobilization

On receiving the Serbian response, Austria-Hungary immediately broke diplomatic relations, and planned tocommence war on 10 August, when mobilization would be completed. The Kaiser, however, returned from his cruise, and on 28 July learned the full story of events during his absence. Whether from sober second thoughts, or merely panic, his reaction was that Belgrade’s compliance with most of the demands meant ‘every reason for war disappears’. He suggested that in order to satisfy her honour, Austria should occupy the Serbian capital and then negotiate. However, his attempt to restrain Vienna was negated by the officials in Berlin. Bethmann-Hollweg did not relay the message until the evening of 28 July, and he omitted the crucial sentence that war was no longer necessary. By this time, Austria had already declared war on Serbia.

After the Serbian reply of 25 July, Ambassador Szogyeny had telegraphed to Berchthold that Bethmann-Hollweg and Jagow were still advising the Austrians to act immediately and confront the world with an accomplished fact. .Later, as British intervention in the dispute became more likely, Bethmann panicked and sent a series of telegrams to Vienna urging restraint. But Moltke was urging Vienna to push forward! Divided authority in Berlin assured recklessness in Austria, her junior partner.

The Serbian mobilization strengthened the hands of extremists everywhere. Only a few hours later, on 25 July, Austria ordered partial mobilization on the Serbian front, to begin on 28 July. On 25 July both Germany and Russia themselves began to prepare for mobilization. When her mobilization began on schedule on 28 July, Austria declared war on Serbia. War had come at that moment because Vienna felt in danger of being diverted into unwanted negotiations with Serbia.

Meanwhile, a double miscalculation had been made. Just as Austria expected Germany to neutralize a threat from Russia, the Russians hoped that their alliance with France, and British diplomatic pressure, would isolate Vienna. In fact, though Serbia was sometimes a nuisance and an embarrassment, Russia could not see her

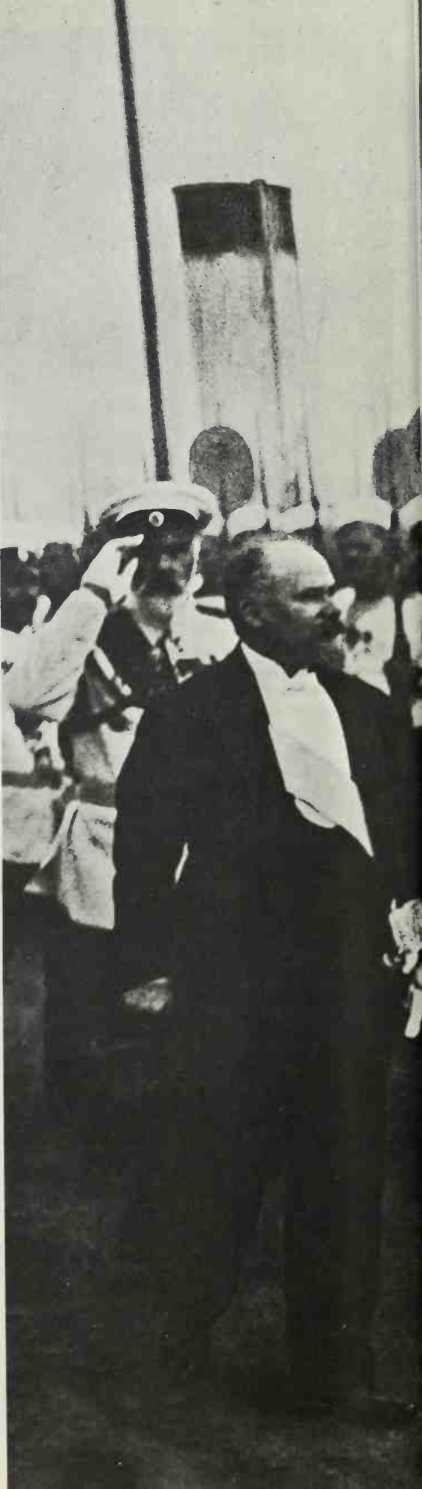

President Poincare visits Tsar Nicholas II and the Russian fleet; 25 July 1914

Protege eliminated without in effect alxlieating ;ts a great power. 1 fowe er, tlie Russians had ad ised Belgrade to eonciliale the. strians and rely on the justice ofthc gre;it powers, but little notice was taken ol this counsel. I'hc Serbians were aware of their influence on Russian altitudes; and indeed, Sazonov warned Pourtales, the German ambassador in Saint Petersburg, that ‘if Austria swallows Serbia we will make wai on her’.

Frtmce was prepared to fulfill her treaty commitments to Russia, but on the whole she |)layed a moderating inlluence thronghonl the crisis. In a sense, she could do liltle else, for although the French state isit to Russia lasted only from ¦20 23 July, the I'rench leaders, Poincare and ’iviani, were away from I’aris from 15 28 July, during w hich time policy-making machiner was paralyzed.

World History

World History