As we have seen, the economic setbacks experienced by the United States throughout the late 1770s and most of the 1780s were followed by years of halting progress and incomplete recovery. Then, in 1793, only four years after the beginning of the French Revolution, the French and English began a series of wars that lasted until 1815.34 During this long struggle, both British and French cargo vessels were drafted into military service, and both nations relaxed their restrictive mercantilist policies. Of all nations most capable of filling the shipping void created by the Napoleonic Wars, the new United States stood at the forefront.

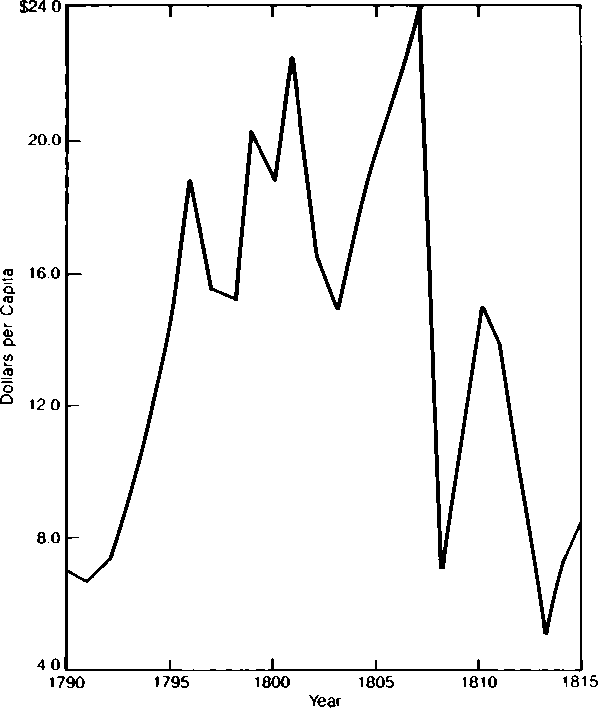

Because of these developments, the nation’s economy briskly rebounded from the doldrums of the preceding years. The stimulus in U. S. overseas commerce is graphed statistically in Figure 7.1. As indicated, per capita credits in the balance of payments (exports plus other sources of foreign exchange earnings) more than tripled between 1790 and the height of war between the French and English. Overseas trade as a proportion of national income during these years is discussed in Economic Insight 7.1. These were

FIGURE 7.1 Per

Capita Credits in the U. S. Balance of Payments, 1790-1815

Source: North, Douglass Cecil. “Early National Income Estimates for the United States.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 9(3), April 1961. Reprinted by permission of the University of Chicago Press.

Extraordinary years for America—a time of unusual prosperity and intense economic activity, especially in the eastern port cities. It was a time characterized by full employment and sharply rising urbanization, at least until 1808. Famed entrepreneurs of New England and the Middle Atlantic region, such as Stephen Girard, Archibald Gracie, E. H. Derby, and John Jacob Astor, amassed vast personal fortunes during this period. These and other capital accumulations added to the development of a well-established commercial sector and eventually contributed to the incipient manufacturing sector.

It is important to recognize the significance of the commercial sector of the economy as well as the role of the merchant class during these decades. The growing merchant class, of course, had played an active role spearheading the move for national independence. Now the merchant class supplied the entrepreneurial talents required to take full advantage of the new economic circumstances. As the spreading European war opened up exceptional trade opportunities, America’s well-developed commercial sector provided the needed buildings and ships as well as know-how. In short, both the physical and human capital were already available, and in many ways, the success of the period stemmed from developments that reached back to colonial times. It was exactly that prior development that singled out the United States as the leading neutral nation in time of war. Rather than the ports of the Caribbean, Latin America, or Canada, those of the United States emerged as the entrepots of trade in the western Atlantic.

OVERSEAS TRADE AND TOTAL INCOME

How big was overseas trade as a proportion of national income? Was overseas trade large enough to merit the emphasis it has been given here? To answer these crucial questions, some calculations are in order.

Taking 1774 as a benchmark year, we see from Table 2.1 (page 37) that about 2.4 million people lived in the colonies. From Table 5.4 (page 91), we determine that average yearly incomes were about ?10.7 (using the 3.5-to-1 capital output ratio). Total income was therefore ?25.7 million (?10.7 x 2.4 million).

From Table 4.5 (page 73), we can sum commodity exports, plus ship sales, plus invisible earnings (but excluding British expenditures on military personnel) to show the average yearly values (1768-1772) of incomes from overseas trade and shipping activities. These were probably slightly below 1774’s earnings, so we have a lower bound of ?2,800,000 (exports) + ?140,000 (ship sales) + ?880,000 (invisible earnings) equaling ?3.82 million. We can conclude, therefore, that income from overseas trade and shipping was nearly 15 percent of total incomes.

An added argument for stressing overseas economic activities is that these were market activities, ones that led the way in moving resources from lesser - to highervalued uses. It was this commercial sector—not subsistence farming, hunting, woodcutting, and the like— that provided the chief stimulus to market expansion, economic specialization, technology transfer, capital accumulation, and advancing productivity and standards of living. Finally, if the coastal intercolonial trades are added to the overseas trade and shipping earnings (15 percent of total income), the combined proportion approaches one-fifth of total income.

The result of this quantitative analysis of the magnitudes of overseas (and coastal) trade, along with the arguments advanced here based on economic growth theory, urges our emphasis on this sector as a leading one for the economic progress of the colonies.

The western movement and the persistence of selfsufficient activities cushioned the downfall of incomes per capita. Undoubtedly, per capita internal trade did not decline to the same extent as per capita exports. (Unfortunately, we have no statistics on domestic trade during that hectic period.) Thus, the external relations probably exaggerated the overall setbacks of the period. It is safe to conclude, however, that the political chaos of the early national era was accompanied by severe economic conditions. Indeed, the problems of government contributed to the weakness of the economy, and economic events in turn clarified government failings under the Articles of Confederation.

These were the circumstances entering 1793, the year in which the Napoleonic Wars erupted and Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin. The sweeping consequences of those events could never have been foreseen in colonial times. The colonies, however, had already developed a commercial base that now would prove crucial to further development. Because of its early efforts at overseas trade, the new nation was ready to take quick advantage of the economic opportunities available to a neutral nation in a world at war.

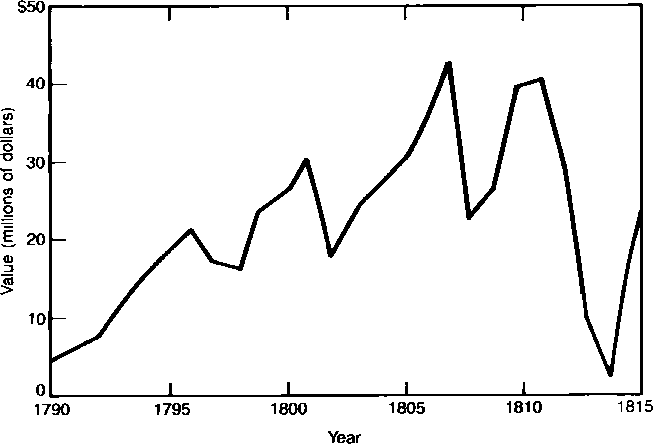

The effects of war and neutrality on U. S. shipping earnings are shown in Figure 7.2. In general, these statistics convey the same picture illustrated in Figure 7.1, namely, that these were exceptionally prosperous times for the commercial sector.

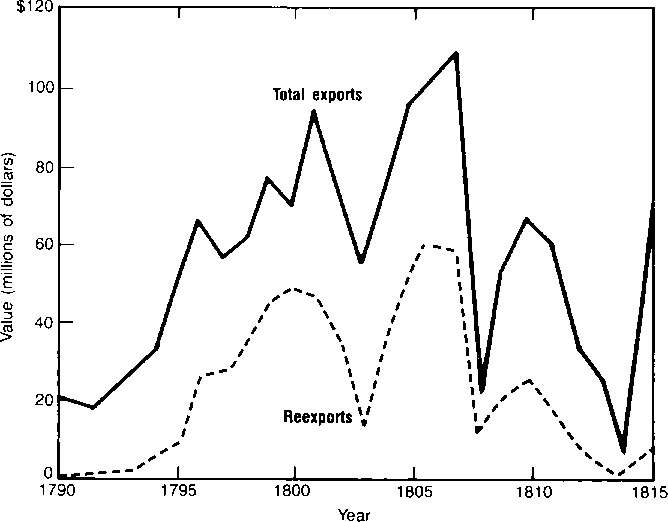

Although the invention of the cotton gin stimulated cotton production and U. S. cotton supplies grew in response to the growth of demand for raw cotton in English textile mills, commercial growth was by no means limited to products produced in the United States. As Figure 7.3 shows, a major portion of the total exports from U. S. ports included re-exports, especially in such tropical items as sugar, coffee, cocoa, pepper, and spices. Because their commercial sectors were relatively underdeveloped, the Caribbean islands and Latin America depended primarily on American shipping and merchandising services rather than on their own.

Of course, such unique conditions did not provide the basis for long-term development, and (as Figures 7.1, 7.2, and 7.3 all show) when temporary peace came between late 1801 and 1803, the U. S. commercial boom quickly evaporated. When hostilities erupted again, the United States experienced another sharp upswing in commercial activity. This time, however, new and serious problems arose with expansion. In 1805, the British imposed an antiquated ruling, the Rule of 1756, permitting neutrals in wartime

FIGURE 7.2 Net

Freight Earnings of U. S. Carrying Trade, 1790-1815

Source: North, Douglass Cecil, Economic Growth of United States 1790-1860, 1st Edition, © 1961, pp. 26, 28. Reprinted by permission of Pearson Education, Inc., Upper Saddle River, NJ.

FIGURE 7.3 Values of Exports and Reexports from the United States, 1790-1815

Source: North, Douglass Cecil, Economic Growth of United States 1790-1860, 1st Edition, © 1961, pp. 26, 28. Reprinted by permission ofPearson Education, Inc., Upper Saddle River, NJ.

To carry only those goods that they normally carried in peacetime. This ruling, known as the Essex Decision, was matched by Napoleon’s Berlin Decree, which banned trade to Britain. As a result, nearly 1,500 American ships and many American sailors were seized, and some were forcefully drafted into the British Royal Navy. The Congress and President Thomas Jefferson, fearful of entangling the United States in war, declared the Embargo Act of 1807, which prohibited U. S. ships from trading with all foreign ports.

Basically, this attempt to gain respect for American neutrality backfired, and as the drastic declines in Figures 7.1, 7.2, and 7.3 convey, the cure was almost worse than the disease. As pressures in the port cities mounted, political action led to the NonImportation Act of 1809. This act partially opened up trade, with specific prohibitions against Great Britain, France, and their possessions.

Nevertheless, continuing seizures and other complications between the United States and Britain along the Canadian border finally led to war—the second with England within 30 years. The War of 1812 was largely a naval war, during which the British seized more than 1,000 additional ships and blockaded almost the entire U. S. coast.

As exports declined to practically nothing, new boosts were given to the tiny manufacturing sector. Actually, stirrings there had begun with the 1807 embargo, which quickly altered the possibilities for profits in commerce relative to manufactures. As prices on manufactures rose, increasing possibilities for profits encouraged capital to flow into manufacturing. From 15 textile mills in 1808, the number rose to almost 90 by 1809. Similar additions continued throughout the war period, but when the Treaty of Ghent in 1814 brought the war to a close, the textile industry faltered badly. Once again, British imports arrived in massive amounts and undercut prices, which had been temporarily inflated by supply shortages resulting from the embargo and the war. Only large-scale U. S. concerns weathered the competitive storm, and there were few of these—most notably the Lowell shops using the Waltham system of cloth weaving (see Chapters 10 and 11). Nevertheless, the war-related spurts in manufacturing provided an important basis for further industrial expansion, not only in textiles—the main manufacturing activity of the time—but also in other areas. This marked a time when the relative roles of the various sectors of the economy began to shift. Agriculture was to dominate the economy for most of the century, but to a lesser and lesser degree as economic growth continued.

The economic surge of the early Napoleonic War period (1793-1807) was unique, not so much by comparison with later years as by its striking reversal and advance from the two decades following 1772. Work by Claudia Goldin and Frank Lewis shows that during the decade and a half after the beginning of the Napoleonic Wars, the growth rate of per capita income averaged almost 1 percent per year, with the foreign sector accounting for more than 25 percent of the underlying sources of growth (Goldin and Lewis 1980, 6-25, and especially page 22).35

In contrast, during the two decades preceding 1793, per capita exports fell (see Table 7.2). Goldin and Lewis estimate that per capita income declined by a rate of 0.34 percent annually from 1774 to 1793 (Goldin and Lewis 1980, 22-23). Wealth holdings per capita also declined substantially over this period (Jones 1980, 82).

Finally, recent research by Lindert and Williamson (2011) provides benchmark estimates of income per capita for 1774 and 1800 suggesting a 27 percentage decline. The sharp and severe declines from the war destructions and independence up to 1793 had not yet been fully countered by 1800, despite the 1793 upturn.

Several decades following independence were exceptionally unstable, not merely two decades of bust and then one and a half of boom. There were ups and downs within these longer bust-and-boom periods. Because of the importance of foreign trade at the time, export instability had strong leverage effects throughout the economy. Although external forces were always an important factor in determining economic fluctuations, as the influence of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) reminded U. S. consumers, workers, and businesses in the 1970s, their almost total dominance was now beginning to wane. By the turn of the century, internal developments— especially those in the banking sector—had assumed a more pivotal role in causing

This bustling dockside scene in the late-1800s shows the emergence of New York City as a center of world trade.

Economic fluctuations. As we shall see in Chapter 12, both external forces (acting through credit flows from and to overseas areas) and internal forces (acting through changes in credit availability and the money stock) came to bear on the economy during the early nineteenth century. And some of the biggest challenges and opportunities for young Americans were settling and working new lands in the West.

World History

World History