A Pew poll in 2008 unearthed another major attitudi-nal difference between Boomers and Millennials. When asked whether immigrants strengthened the country with their hard work and talent, or burdened it because they took jobs, housing, and healthcare, the Boomers overwhelmingly (50 percent to 30 percent) regarded immigrants as a burden, while Millennials overwhelmingly (58 percent to 32 percent) thought immigrants strengthened the country. One reason for the attitudinal change is that a far higher proportion of Millennials are themselves immigrants or the children of immigrants.

Immigration is a global phenomenon that has transformed the United States in the past forty years. But while it is possible—and even necessary—to consider the subject in terms of large statistical trends,

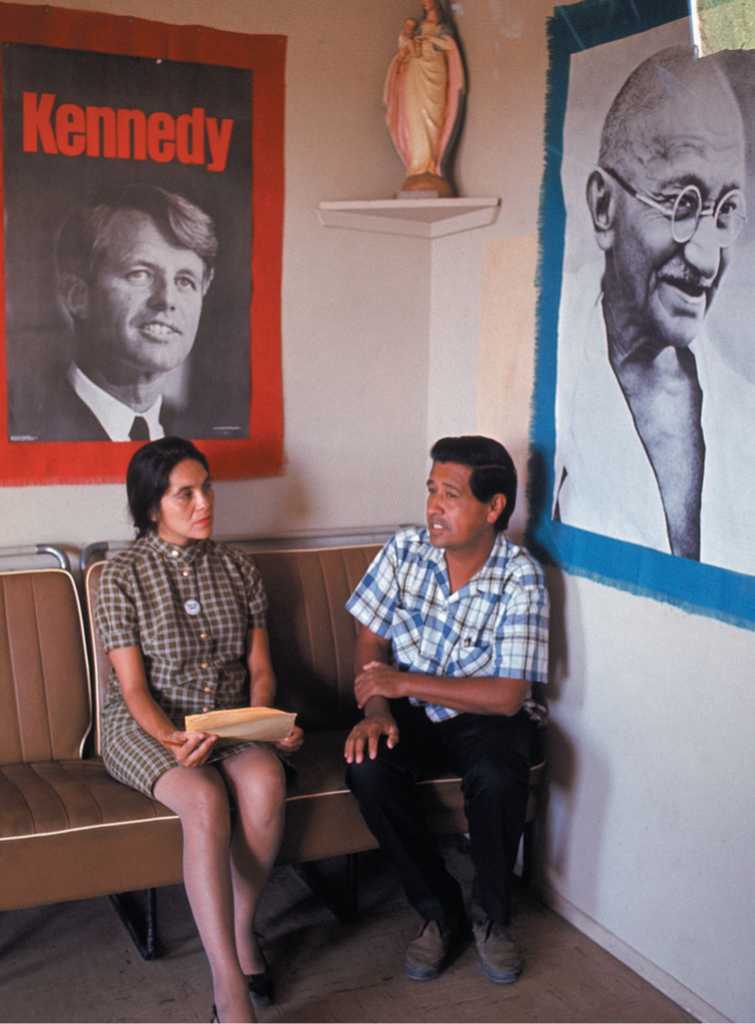

Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez, leaders of the United Farm Workers, discuss their 1968 strike of grape pickers. They are framed by photographs of Robert Kennedy, campaigning for the Democratic nomination for president, and Mohandas Gandhi, leader of the non-violent protest movement that won independence for India in 1947.

Every county and city has its particular immigration narrative. Indeed, as countless population streams have for centuries flowed into that heaving ocean of peoples that is the United States, every family’s immigrant history is irreducibly unique, as the American Lives essay about “Barack Obama” demonstrates (see pp. 824-825).

Since 1924, immigration to the United States had been governed by a quota system that ensured that the distribution of new immigrants mirrored the nation’s existing ethnic patterns (see Chapter 24, p. 640). But the Immigration Act of 1965 eliminated the old system. It instead gave preference to immigrants with specialized job skills and education, and it allowed family members to rejoin those who had immigrated earlier. In 1986, Congress offered amnesty to illegal immigrants who had long lived in the United States and penalized employers who hired illegal immigrants in the future. Many persons legalized their status under the new law, but the influx of illegal immigrants continued. Together, these laws enabled more than 25 million to immigrate to the United States from 1970 to 2000.

Asians, many of whom possessed skills in high-tech fields, benefited most from the abandonment of the “national origins” system. Of the 9 million Asians who immigrated to the United States during these years, most were from China, South Korea, India, Pakistan, and the Philippines. Following the defeat of South Vietnam and the Khmer Rouge takeover over Cambodia, some 700,000 South Vietnamese and Cambodians received refugee status.

From 1970 to 2000 the largest number of immigrants were Latinos, sometimes called Hispanics (16 million). By 2000, the Latino population of the United States (35 million) for the first time exceeded African Americans (34 million). The overwhelming majority of these Spanish-speaking immigrants were Chicanos—Mexican Americans who settled in the Southwest. (Of the nation’s 35 million Hispanics, 11 million lived in California, and nearly 7 million in Texas; over 42 percent of the population of New Mexico was Latino.) In addition, several million Puerto Ricans came to the mainland United States, most of whom settled in well-established Puerto Rican neighborhoods in northeastern cities. About a million Cuban immigrants arrived in Florida during these years.

But immigration was far more complex than the aggregate data suggest. Dearborn, Michigan, headquarters of the Ford Motor Company, is in many ways the prototypical American city. Yet nearly a third of its 100,000 residents are Arab-speaking immigrants from Lebanon, Iraq, Yemen, and Palestine.

Lowell, Massachusetts, whose textile mills employed young women from New England farms during the 1820s and 1830s, is now home to some

20,000 Cambodians, refugees from the regime of Pol Pot, a communist dictator who killed some 2 million of his own people.

About 10,000 Sudanese, refugees from a genoci-dal war in Africa, have flocked to Omaha, Nebraska, to work in its meatpacking plants. Nearly as many Bosnians, refugees from a civil war in the Balkans, have settled in Boise, Idaho.

Nearly every community had its own immigrant narrative, but some patterns were broadly applicable. As whites left for the suburbs and businesses relocated to the malls, immigrants moved into vacated city housing and established businesses downtown. In Los Angeles, for example, Korea Town, Japan Town, the Latino barrio, and South Central districts sprouted almost overnight.

In many communities, the new immigrants became a significant political force. Latinos elected mayors in Los Angeles, Miami, Denver, and San Antonio. Cesar Chavez, a pivotal figure in the history of Mexican Americans (Chicanos), succeeded in bringing tens of thousands of Mexicans into his United Farm Workers union. In a series of well-publicized strikes and boycotts, Chavez and the UFW forced wage concessions from hundreds of growers in California, Texas, and the Southwest.

But the infusion of immigrants generated concern. In 1992 Patrick Buchanan, campaigning for the Republican nomination for president, warned that the migration of “millions of illegal aliens a year” from Mexico constituted “the greatest invasion” the nation had ever witnessed. By then, about one-third of the Chicanos in the United States had arrived without valid visas, usually by slipping across the long U. S. border with Mexico. Of particular concern was the fact that the Latino poverty rate—which hovered around 10 percent—was twice the national average. In 1994 California passed Proposition 187, which made illegal immigrants (“undocumented aliens”) ineligible for social services, public education, and nonemergency medical services. (The U. S. Supreme Court struck the law down as an infringement of federal powers. In 2001 the Supreme Court ruled that immigrants were entitled to all the protections the Constitution afforded citizens.)

Conservatives were not alone in opposing illegal immigration. Loose immigration policies suppressed wage rates; often illegal immigrants were recruited as strike breakers. Many labor leaders blamed the post-1965 influx of immigrants for the decline in union memberships. Chavez argued that illegal immigration

World History

World History