When the North Koreans attacked South Korea at the end of June 1950, Truman and Acheson immediately deployed US troops to defeat the aggression and asked the United Nations for its support. US officials were surprised by the invasion, but had no doubt that it was orchestrated in the Kremlin. Truman and Acheson believed that it was a test case of their will. If the United States did not respond, American credibility would be shattered and more important friends and prospective allies, such as the Japanese and West Germans, would lose faith in US power. Certainly, if they did not respond, Republican critics at home would condemn them for their timidity in the face of aggression.

The North Korean attack confirmed the suspicions of Truman, Acheson, and Nitze that the Soviets were becoming bolder as they gained strategic might.96 The United States, therefore, not only had to thwart the attack, but also needed to reestablish the aura of military superiority that was deemed critical for the success of their diplomacy and their strategic vision. Truman asked Congress for funds not simply to wage the war in Korea but to support the concepts enumerated in NSC 68. The aim was to contain and roll back Soviet power without risking all-out war.

Truman, Acheson, and their advisers were convinced that the Kremlin, while bolder, still did not seek conflict with the United States. Hence when General Douglas MacArthur launched a successful invasion at Inchon and drove North Korean troops back to the thirty-eighth parallel that had divided

North and South Korea, Truman decided that the United States and its allies should cross the prewar border, liberate North Korea, and unite the peninsula as part of the free world. Betting that the Chinese and the Soviets would not intervene because they would not risk hostilities with the United States, they allowed MacArthur to move to the Yalu River on the Chinese-Korean border. The impending defeat of their North Korean friends and the specter of a hostile United States on their very border triggered the intervention of the Chinese Communists in November 1950.

The escalatory spiral profoundly worried officials in Washington. They still did not think Stalin would intervene directly, but their confidence was shaken. They wanted to dissuade Stalin from even thinking about initiating hostilities in Europe. They were determined to build superior power and capitalize upon it. Truman deployed four US Army divisions to Western Europe and helped transform the North Atlantic Treaty into a viable defensive organization. The president also approved gigantic new defense expenditures. During fiscal years 1951 and 1952, Truman planned to spend the staggering sum of about $140 billion to pay for national security programs. Compared to June 1950, by mid-1952, the US Army would have 1,353,000 troops rather than 655,000; the navy would have 397 major combatant vessels rather than 238; the air force would have 95 wings rather than 48. Since only $3-$5 billion per year was being spent in Korea, the vast majority of the money was allocated to cast the shadows necessary to support US diplomacy.

Now was the time, Acheson and Nitze were convinced, to take the initiatives that were fraught with risk, but that were essential to preserve long-term strategic predominance. They authorized plans to rearm and link West Germany to NATO. When the French reacted with consternation, US officials embraced a French plan to establish a European Defense Community that would include German troops, but no German general staff. The overarching design of the Truman administration was to lock West Germany and Japan into permanent association with a Western alliance system spearheaded by the United States. To do this, additional risks had to be taken to cede more sovereignty to the West Germans and the Japanese in return for their promises to stay aligned with the West and to allow the United States to use their territories to enhance its strategic reach. The Kremlin remonstrated against these actions, but Truman, Acheson, and Nitze gambled that Stalin would avert war. "It was felt," said Nitze, "that the risk of provocation had to be taken, otherwise we were deterred before we started."97

At the same time, Truman, Acheson, Nitze, and their associates did not forget the importance of the periphery in relation to the industrial core areas of Eurasia. The United States increased its strategic reach in the eastern Mediterranean and Southeast Asia. The United States championed the incorporation of Greece and Turkey into NATO. It established the ANZUS alliance with Australia and New Zealand. It worked with Britain, Turkey, Egypt, and others to design a Middle East Command. It provided vast sums of money to support French efforts to defeat Ho Chi Minh’s Communist forces in Indochina. Acheson and Nitze did not want US policymakers to be self-deterred in the future as they felt themselves to have been in Korea when they hesitated to attack China directly lest they trigger the intervention of the Soviet Union. In the future, Nitze emphasized, the United States "must be willing to face the danger of war with the Soviet Union." In the future, Acheson emphasized, freedom of choice must remain "with us, not the Russians."98

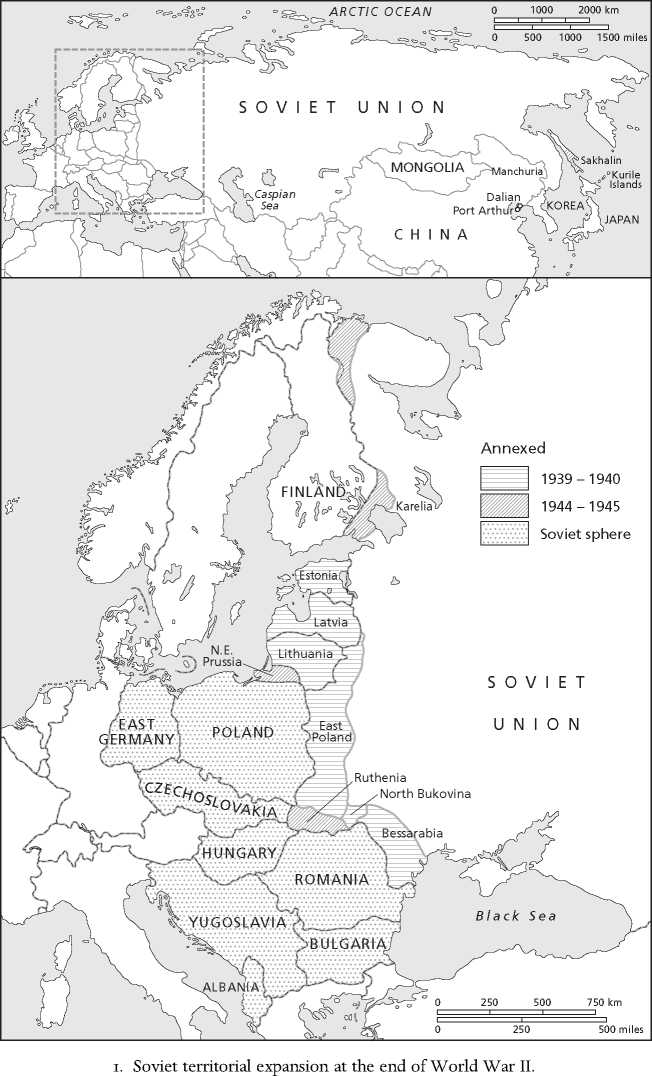

From an inchoate beginning, Harry Truman and his advisers had transformed the strategic posture of the United States in the postwar world. Their overriding priority was to prevent a totalitarian adversary from conquering or assimilating the resources of Europe and Asia and using them to wage war against the United States, as the Axis powers had done during World War II. Even if the United States were not attacked, as it had been at Pearl Harbor, the United States could not be indifferent to Soviet aggression or Communist subversion. "If communism is allowed to absorb the free nations," President Truman explained, "we would be isolated fTom our sources of supply and detached from our friends. Then we would have to take defense measures which might really bankrupt our economy, and change our way of life so that we wouldn’t recognize it as American any longer. That’s the very thing we’re trying to keep from happening."99

The strategy evolved from vague talk about an open world and an international organization to more concrete ideas about the need to rebuild western Germany, reconstruct Western Europe, and rejuvenate Japan. Reviving former enemies, however, posed dangers. Although the Truman administration accepted unprecedented strategic commitments, these military guarantees could not assure success. West Germany, Western Europe, and Japan could not prosper and could not be secure if the periphery gravitated into the hands of revolutionary nationalists and Communists. Risk-taking in the Third World in places such as Indochina, Iran, and the Middle East was the price US officials felt they had to pay for the successful rehabilitation and integration of Northeast Asia, Northwest Europe, and North America into a thriving capitalist community based on democratic values.

The strategy of the Truman administration was never limited to deterrence and containment. The strategy was to wage a cold war and win it. "I suppose," said Truman in his "farewell address" on January 15, 1953, "that history will remember my term in office as the years when the 'cold war’ began to overshadow our lives. I have had hardly a day in office that has not been dominated by this all-embracing struggle - this conflict between those who love freedom and those who would lead the world back into slavery and darkness. And always in the background there has been the atomic bomb. But when history says that my term of office saw the beginning of the cold war, it will also say that in those 8 years we have set the course that we can win it."100

Victory was Kennan’s goal from the outset. Both in the "Long Telegram” and in his even more famous X article in Foreign Affairs, he stressed that prudence, perseverance, and determination would allow the West to triumph, provided it successfully nurtured its own institutions and values. In the strategy papers that he authored and that his successors wrote, the overall objective ofUS policy was more than containment. The aim was to reduce the influence of the Soviet Union and induce a basic change in the Kremlin’s approach to international affairs. Truman articulated this notion well in his last "state of the union” message. If "the communist rulers understand they cannot win by war, and if we frustrate their attempts to win by subversion, it is not too much to expect” that they might change their "character, moderate [their] aims, become more realistic and less implacable, and recede from the cold war they began.”101 The strategy, as it evolved over the decades, had its strengths and weaknesses, but it prevailed.

World History

World History