Mr Sukkumvit

Our walk takes us from what was a century ago swampland on the bank of the Saen Saeb canal, down through the embassy district to the site of Bangkok’s first radio station, and then back up to the beginning of modern Bangkok.

Duration: 2 hours

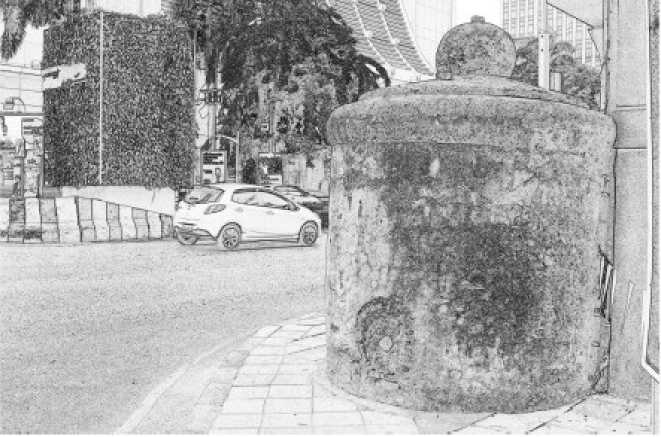

On the corner of Ploenchit and Wireless roads stands a curious object. About three metres (10 ft) high and cylindrical in shape, it is made of concrete and is entirely blank. No door, no window, nothing. From time to time it has provoked lively comment in the letters page of the English-language newspapers, where it has generally been referred to as The Thing. Is it a wartime pillbox, part of the pumping apparatus for the nearby Saen Saeb canal, a toilet, or something to do with the sewers? For the answer we have to go back many years, to a remarkable man.

Lert Sreshthaputra was born in 1872 to a well-respected Bangkok family that lived near the southern end of the second moat. Young Lert showed early signs of being a very enterprising person, having his birthdate changed by a venerated monk to give himself a more auspicious astrological sign. When his schooling was finished he worked as a clerk for the soda water and soft drinks section of the Singapore Straits Company, which later became known as Fraser & Neave. By the age of 22 he had risen to be a partner in the business, but his ambitions went far beyond this: he had saved enough money to set up on his own, and he opened a store on Charoen Krung Road, near to where it crosses the Padung Krung Kasem Canal. By now he was called Nai Lert, or Master Lert, and this is the name that appears above the shopfront in old photographs. Nai Lert’s store began by selling sewing machines, canned foods, carbonated lemonade, and other imported goods, and it prospered. Nai Lert gained more fame when in about 1910 he imported the new ice-making equipment, being the first person in Siam to be able to solidify water, an art that drew astonished crowds to such an extent that an exhibition was staged in the Sala Sahathai building, next to the Temple of the Emerald Buddha.

Around the time Nai Lert opened his store, the tram service along Charoen Krung Road had been electrified, and the street was evolving as the most fashionable shopping district in town. And then something else happened. Around 1900 the first motorcar appeared in Siam. Owned by Chao Phraya Surasak Montri, the vehicle was of an unknown make and was described by an envious noble as looking like a steamroller set on solid rubber tyres and topped off by a flat roof. Possessing a feeble engine sufficient to propel the vehicle along level ground but without the power to climb humped bridges, it nonetheless required fuel. When in 1904 a son of Rama V, travelling in Europe, ordered a Daimler-Benz to be delivered to Siam, which he then presented to his father, a motorcar was something every wealthy Siamese wanted to own. This proved a decisive time for Nai Lert, who took on the concession for Shell motor spirit. His store became one of Bangkok’s few filling stations, and he expanded the premises. Motorcars did not remain a novelty for long. Nai Lert had started a horse-drawn carriage service for hire to the affluent to tour the city’s new roads, and in 1910 this evolved into a bus service using engine-driven vehicles, importing the motors from England and appointing a team of local carpenters to build the bus bodies, following a design that Nai Lert himself sketched out with chalk on the cement floor of his shop. A distinctive white colour, the first White Bus route ran from

Pratunam to Siphraya Road, and this was followed by the White Boat service that ran along the Saen Saeb canal, bringing people in from as far afield as Nongchock and Minburi, where they disembarked at Pratunam. He imported Fiat motorcars and rented them out with drivers by the hour, starting Bangkok’s first taxi service. He built pleasure boats and sea-going vessels that fished the Gulf of Siam and transported goods to and from provincial towns along the coast. He built the Hotel de la Paix, in the Saphan Lek Bridge area, which offered English beer, Scotch whisky, and tasty sausages made by his wife. King Rama VI came to lunch shortly after it opened.

In 1915 Nai Lert did something that really made people shake their heads in disbelief. He purchased, from the royal family, twenty-five acres of swampy land alongside the Saen Saeb canal. Bounded by what are now the top part of Wireless Road, Ploenchit Road, and Soi Chit Lom, the investment seemed a whimsical one. The city was spreading outwards in the southeast, the Bangkok Sports Club was not that far away, and there were several big houses a little liorther to the south of Nai Lert’s land. But in the area of the canal the ground was soggy, and best used for growing rice. In fact rather than attempt to cross the rough and marshy ground by vehicle, Nai Lert himself travelled by canal to inspect his new acquisition. To ensure there was no mistake as to the ownership of the land in this wilderness, Nai Lert set up a series of massive stone boundary markers in the shape of upended cannon barrels and various forms of ordnance. There were six of them, and only The Thing remains. Another Thing, in the form of a bullet, existed outside the Swissotel Nai Lert Park until 2003, when it was hit by a car and destroyed.

In 1922 the British finally made up their minds to leave the riverside compound on Charoen Krung Road, having been offered almost half of Nai Lert’s plot of land, some twelve acres, at an advantageous price that allowed them to both buy the land and erect the new embassy buildings from the proceeds of the sale of their original site. The misgivings of the British minister, Sir Robert Hyde Greg, who was something of a traditionalist, were mollified by the designs for the new Residence. The first structure to be erected was the war memorial, paid for by British subjects in Siam and unveiled in 1923. The statue of Queen Victoria was transported to the site (the statue was boarded up by the Japanese in World War ii., but they thoughtfully provided a peephole so that Her Majesty would not be left in complete darkness), and Sir Robert took up residence in the completed compound in 1926. The embassy has in recent years sold of the section of land facing onto Ploenchit Road, which is being developed by Central Group as a hotel and other commercial property. Not a bad move, all in all, as this has always been a rather glum corner, with its high, grey wall. But I do worry about the future of The Thing, which is looking rather decrepit these days and could well fall victim to any official who decided it was an unsafe structure. Losing this humble but significant landmark would be a great pity.

Soon after he had bought the land, Nai Lert had built a teak house next to the canal where he would take his family fiom time to time to escape the turmoil of Charoen Krung, where they had their main residence and where the company offices were located. Towards the latter part of the 1920s he decided to move his family full-time to the peace and quiet of his canal-side property, and a second house was built there, a small canal and a pond dug, and spacious gardens laid out. Today the property is known as Nai Lert Park and lies directly behind the Swissotel, which is owned by his descendants. Standing on eight-a-half acres it had opened as the Hilton International in 1983, and occupies the land on which Nai Lert built a depot for his White Bus Company A bronze statue of Nai Lert is seated near the entrance, although the beautiful white automobile that had belonged to him and was parked alongside the statue was moved to the house after the destruction of the boundary marker, on the perfectly reasonable assumption that if a Bangkok driver can destroy a ten-foot high stone bullet with a single blow, a vintage motorcar would not

Stand a chance.

Descend the flight of steps that leads down from the hotel main entrance, follow the pathway to the bank of the canal, and you will find one of the city’s most curious shrines. Chao Mae Tuptim is a female spirit, tuptim being the Thai word for both ruby and pomegranate. No one knows quite how long this shrine has been here, or why. Very possibly it dates back to the early days of the canal, with scattered villages along the banks and passing boats stopping to make offerings. A large fichus tree stands here, and these trees, with their twisting aerial roots, are traditionally regarded as an abode for spirits. Why it was decided the tree was the home of the goddess Tuptim is a mystery, as is the goddess herself, and her reputation for fertility. It only takes a few wishes to come true, and a shrine can achieve a reputation. Whatever the history is, the tree and its spirit house has drawn generations of supplicants bearing the offerings of phalluses, and hundreds of them have been left here. Some are tiny and placed in the branches, some are baked like cakes and left to dissolve into the elements, and some are real whoppers, elaborately carved from wood and painted in varying shades of red and pink.

Although Ploenchit Road may have looked remote to the British legation staff gloomily contemplating a long trudge from their comfortable homes in Bangrak or Bang Kolaem, to the British sea captains who had previously only to step of the deck of their ship and into the embassy garden to get their paperwork sorted, and to the servants who quite possibly had fears of crocodiles and tigers, the new British Embassy by 1926 was not really that remote. The tram rattled up Silom Road as far as Pratunam, the roads were good enough for the motorcars that were becoming commonplace, and there was always a boat ride along the canal that was eventually to become Wireless Road. Civilisation ended in fields and pathways where Sukhumvit now runs, true enough, but on the immediate south side of Ploenchit Road, or the trail that passed for Ploenchit Road, were

Some very desirable residences.

Take, for example, the house of an Englishman named Henry Victor Bailey, a wealthy adventurer who settled in Siam and ran an architectural practice, along with importing motorcars and blue-and-white porcelain from China. Bailey designed and built a house for himself here in 1914. A large timber residence, large enough to house himself and his three Siamese wives, it stood on stilts and had a broad veranda and a billiards room. Bailey died in 1920, and the house was sold to the Siamese Treasury. In 1947, after the conclusion of World War II., Thailand, in a gesture of appreciation to the United States, handed over the property and ten acres of manicured gardens for use as the official residence of the American ambassador, which it remains to this day. Then there was Wittayu Palace, built for Prince Rangsit in 1925. The prince had studied in Germany, and he was also an avid collector of Asian and European antiques. When his collection became too large for his palace at Pomprabsatrupai, the prince had bought land here and commissioned Swiss architect Charles Berger Lang to design a new palace in a Swiss-German style. The prince designed the interiors himself, and asked the architect to specify a thick wall so that he could maintain a constant temperature for his fragile collection. Prince Rangsit died of a heart attack in this house in 1951, and it passed to his descendants, who maintain the house and its collection in its original form. Then there was the residence of Dr Alphonse Poix, a French doctor who was a physician to Rama V. A white-painted two-storey structure with a three-storey tower and beautifully carved gables, the house was built in the last years of the nineteenth century and in 1948 was purchased by the Dutch government to be used as a residence for their ambassador.

The coming of the British Embassy to this part of the city had a profound influence on what was to become known as Wireless Road, because most of the embassies of the world’s leading nations had moved here within twenty or so years. Those that couldn’t find premises in Wireless Road moved into the nearest places they could find, such as Soi Thonson, Soi Ruam Rudee, and the upper part of Sathorn Road. This in turn led to a large population of expatriates in this area, and this led to the establishment of Western schools and kindergartens, of which Ruam Rudee, a quiet thoroughfare whose name translates roughly as “love lane”, became the epicentre. It also led to the founding of one of the world’s oddest Catholic churches, the Holy Redeemer Church on Soi Ruam Rudee, which at first glance and even at subsequent close examination looks like a Thai Buddhist temple. In 1948 the Bishop of Bangkok had asked the Redemptorists to establish a foundation and parish in Bangkok to serve the growing English-speaking population. Four American Redemptorists duly arrived and began searching for a suitable plot of land to build a church. They rented accommodation not far from the site of the subsequent church, and they established a temporary chapel: the chapel appears to have been distinctly makeshift, because with admirable brio they dubbed it Our Lady of the Garage. They eventually found a suitable piece of land, tucked into the L-shape of the lane, and a suggestion by Bishop Fulton J Sheen that the traditional style of architecture be used, was followed. It was an inspired decision. The church, completed in 1954, holds services in Thai and English, and plays, as they say, to packed houses. Holy Redeemer also founded two schools, a local parish school for Thai students and an international school, the latter now located outside the city and one of the most successlial and prestigious of Thailand’s international schools.

So, why is this leafy thoroughfare called Wireless Road? Travel on down to the end of the road and you will find, opposite Lumpini Park, a scene of most awful desolation, at least, at the time of writing. One doesn’t need to be an old-timer to remember when this huge area, fifty-one acres of royal land, was the Armed Forces Preparatory School. Founded here in 1958, it was a parade ground and playing field where cadets drilled and worked out, attended classes in the buildings facing Rama IV Road, and lived in the warren of barracks behind the buildings. In 2000 the school moved out to Nakhon Nayok, and the Suan Lum Night Market moved in. The market always seemed a dodgy venture, with very little security of tenure for the vendors and investors, and a rather strange location for a market that didn’t open until 9 p. m. and had little walk-past trade. It closed in 2011 and the developers bought a large piece of land on Ratchadaphisek Road. Some of the vendors moved there, and some went to Asiatique, on Charoen Krung Road. Suan Lum was bulldozed, and remains to the present as a flat area of rubble and weeds. Except, that is, for a very high radio mast that has a small building at the base, and appears to be a functioning island in a sea of desolation.

Radio, as with so many other technological developments, came early to Siam. Two experimental transmitters were installed in the early years of the twentieth century, one at Golden Mount, high above the city, and the other at Si Chang Island, of the coast of Chonburi. Both were used by the Royal Thai Navy for ship-to-shore communications. In 1919 Rama VI used both these transmitters to proclaim the birth of radio broadcasting in Siam, but the technology was primitive and local resistance to something so unnatural was strong. In the early 1920s Prince Purachatra Jayagara, the Prince of Kamphaengphet, was appointed Minister of Commerce and Communications. He had a natural interest in technology, and installed a small transmitter in his palace at Luang Road, near to the second moat. The test broadcasts proved encouraging, and on 31st May 1928, Station 4PJ, carrying the prince’s initials and broadcast from the Post and Telegraph Office at Wat Liab, went on air. In 1930 the Telegraph Act was amended to allow the public to own radio receivers. To cater for the new demand, a radio station was established at Phayathai Palace.

Nai Left’s cannon-shaped boundary marker outside the British Embassy.

Following the coup in 1932, the national radio station was moved to Sala Daeng, next to the Paknam Railway station. Renamed Radio Bangkok, it had a new call sign, 7PJ, and a 2.5kW transmitter. Tests were also carried out here on a shortwave transmitter, 8PJ, to reach overseas. After World War ii the government, which retained a monopoly on radio broadcasting for many years, built larger and more powerful transmitters elsewhere. But that radio mast poking up from the rubble on the corner of Wireless Road marks one of the starting points.

Visitors staying in the Sukhumvit Road area, or travelling on main roads in other parts of the eastern side of Bangkok, are bewildered by the fact that a railway line runs at ground level through the city. The already clogged traffic comes to a complete standstill at the clanging of a warning bell, the barrier is lowered, and a couple of minutes later a train of seemingly several miles in length clanks its way between the waiting lines of traffic. The railway line is for freight, and links the marshalling yards of Bang Sue, in the north of the city, with the port and oil refinery at Klong Toei. It also marks very clearly, and as effectively as a moat, where the old city ends and the new one begins: for Sukhumvit Road, visible beyond the railway barrier, is an exuberant arterial highway that forms the main hotel, shopping and tourism district, and which beyond the suburbs runs along the eastern seaboard to eventually end 400 kilometres (248 miles) away in the province of Trat, on the Cambodian border.

The Saen Saeb and Bang Kapi canals were dug to the east of the city in the time of Rama III, with the former being the main waterway for agricultural produce and military use, while the latter flowed along what are now Ploenchit and Sukhumvit roads and connected a network of small canals, creeks and drainage ditches that stretched all the way to Klong Toei. In the time of Rama iv, at the request of the newly-arrived Western traders, the Hua Lampong canal was cut eastwards along what is now Rama IV Road to connect the third moat to the river. The land through which these waterways passed represented a rural idyll, with fields, orchards, rice paddies and villages threaded by the waterways.

With the building by Rama IV of Sra Pathum Palace, the eastern part of the city became a popular residential area for nobility and high-ranking officials, with plots of land being used to build country estates. When the Westerners arrived they pushed the city further to the east by opening their embassies in the Wireless Road district, and setting up home there. Nai Lert and an enterprising Indian Muslim named Lek Nana bought large plots of land between the Saen Saeb and Bang Kapi canals, and began to develop them. The trail that ran alongside the Bang Kapi canal was paved as a two-lane road in 1940, as far down as Soi 19. Beyond that, the way remained little more than a track. A large number of Indians began arriving in Bangkok in the 1940s, and they bought up plots of land along the paved road and beyond, where they were able to erect inexpensive housing for

Themselves. With Klong Toei now a modern port, road traffic increased.

Businesses began to move into the area, and the road that was known as the Paknam Trail, as it led towards Paknam, at the mouth of the river, needed to be developed systematically. Canals were filled in, and new roads made. The patchwork of roads and trails grew, evolving into an arterial highway that needed a name. Prasop Sukhum had been the first Thai to study at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, travelling to the United States in the early 1930s, and had been greatly influenced by the American style of highway building. Returning to Bangkok, he started as an assistant engineer with the Department of Sanitation and progressed to the position of chief engineer of the Highways Department. He was responsible for much of the new infrastructure that underpinned Bangkok, as the city developed and grew with astonishing rapidity after World War ii., becoming a megacity whose continuing expansion seems to have no end. So successful was Prasop Sukhum’s career that the king bestowed upon him the formal title of Phra Pisan Sukhumvit. There was an initial suggestion that the highway be named after Lek Nana, who modestly declined, and so Mr Sukhumvit, in 1950, by a casual flip of history’s coin, became world famous for the road that leads eastwards out of the Sea of Mud, absorbing the little farming and fishing villages and leaving the historic districts far behind to create a different kind of Bangkok.

World History

World History