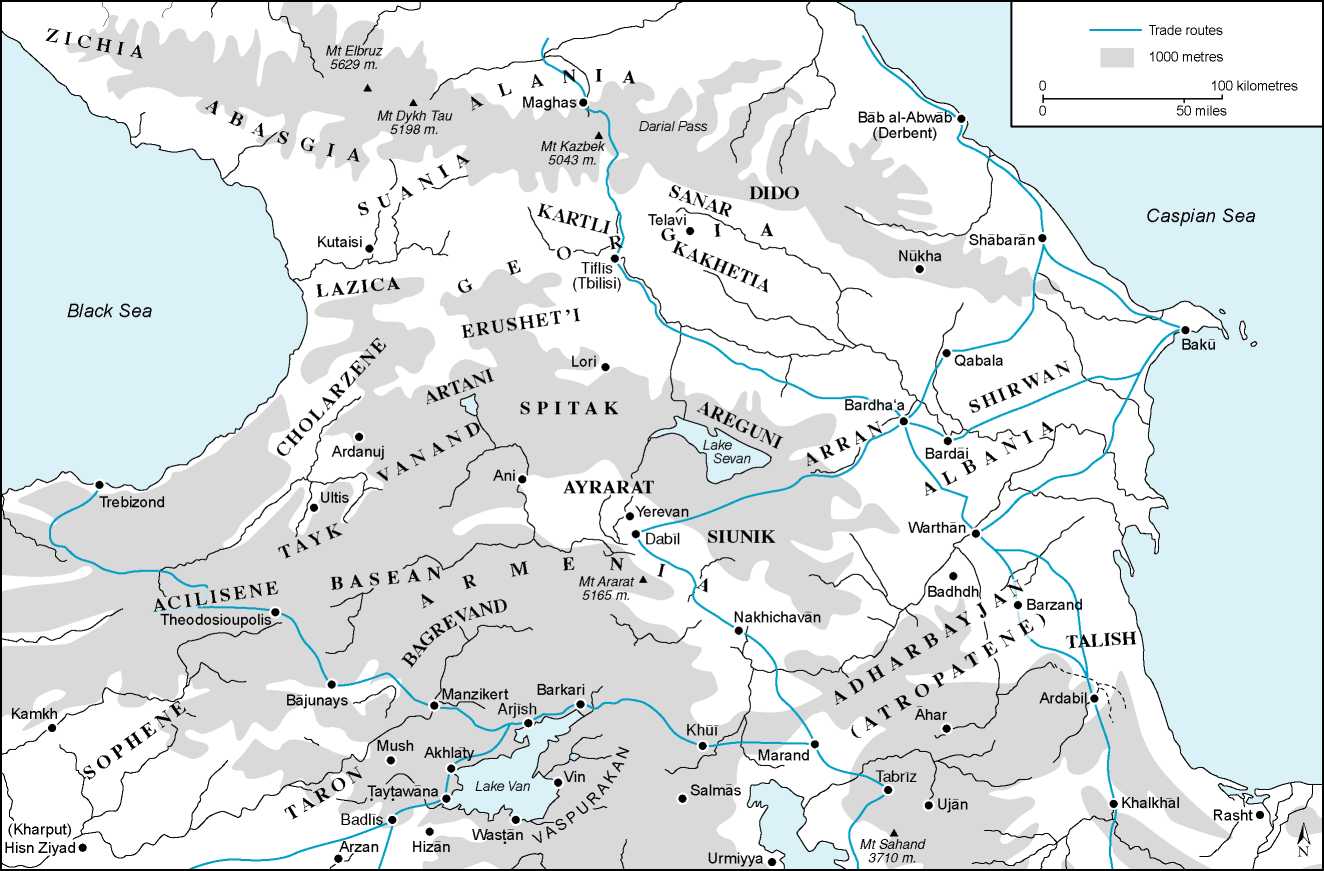

The collapse of the Avar hegemony in the period following the failed siege of Constantinople in 626 resulted within a few decades in their confinement to the plain of Hungary and the emergence of a number of new nomad groups in the west

Eurasian steppe. The most important were the Bulgars and the Khazars. The former included the Onogurs who had been under Avar dominion until they split away and made a treaty with the Emperor Heraclius; and the two groups of Kutrigur and Utigur ‘Huns’, along with several other minor clans, who had been involved with the break-up of the Blue Turk confederacy (ca. 630s). They were in conflict with the Khazars, another faction in this fighting. Khazar victory in the 670s led to the expulsion of several Bulgar groups. Some migrated northwards (to form the later Volga Bulgar group) or westwards (as far as the Pentapolis in north-east Italy, or into Avar territory in Pannonia), and one group moved down to the Danube delta. Under their leader, Asparuch, their request to enter east Roman territory was refused. When they crossed into what was seen as Roman territory in 679/680, the Emperor Constantine IV marched to meet them, but tactical confusion led to a Roman defeat, which

Made possible the foundation of the Balkan Bulgar state (see pages 31-32 and 58). By the early eighth century the Bulgar khans were able to interfere in internal Byzantine politics, and during the eighth century they presented almost as grave a threat to the empire as did the Arabs in the east.

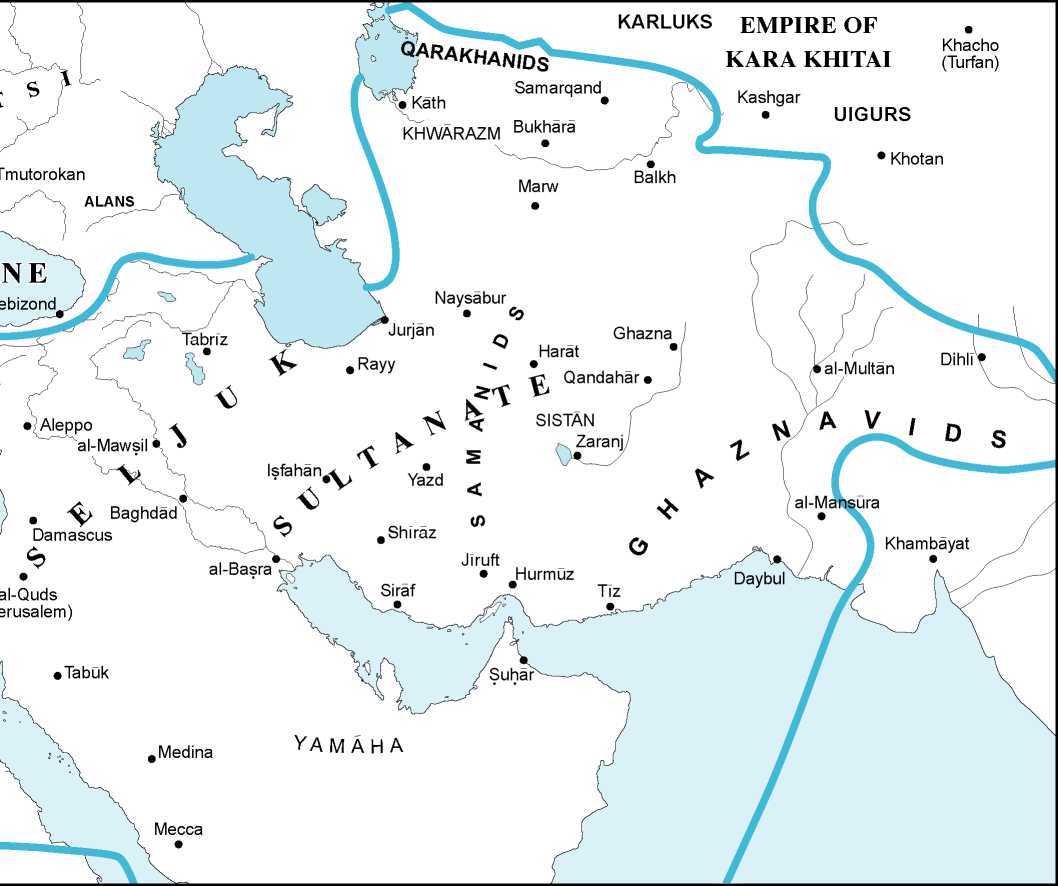

By 680 the Khazars controlled much of the western Eurasian steppe, their leading clan claiming the lineage and rights of the senior clan of the western Blue Turks. They were for Constantinople an important ally against Islam, and mounted several raids into Islamic Caucasian territories, although temporarily checked by a successful Arab offensive in 737. They were also a counterweight to the Bulgars in the Balkans. Two emperors arranged marriage alliances with the Khazars (Justinian II married the Khagan’s sister; Constantine V married a Khazar princess) and other contacts flourished. Tensions over conflicting claims in the Crimea did not hinder

Map 8.7 Armenia, Georgia and Transcaucasia 550-1000.

Map 8.9 The steppes and the Rus’ c. 680-1000.

Otherwise good relations, even after the leading clan converted to Judaism in the eighth century. The kingdom of Abasgia was under Khazar rather than Byzantine protection from 786; and the semi-autonomous Iranian Alans, in the northern Caucasus region, were also tributary. But the Khazar rulers slowly moved away from their steppe nomad roots to derive most of their wealth from commerce, for they controlled the major trade routes across the southern steppe zone and between the northern forests and the south. When a new threat in the form of the Pecheneg and Oguz Turks appeared on their eastern borders, they were able to offer only limited resistance.

The Pechenegs were a Turkic group subject to the rump of the former Blue Turk Khaganate and living in Turkestan. With the dissolution of the Turkic Khaganate, another group, the Oguz, under pressure from the expanding Uighurs, moved westwards. Some Pechenegs remained and joined with the newcomers; others moved away towards Khazaria, dislodging the Magyars, an Ugric-speaking people tributary to the Khazars, who were also pushed westwards. By the 880s effective Khazar control was confined to the steppe north of the Caucasus. The Pechenegs dominated the south Russian steppe, with the advancing Oguz to the east and the Magyars to the west.

Byzantine encouragement to the Magyars to attack the Bulgars in 894-896, combined with Pecheneg pressure, finally pushed the Magyars into the Hungarian plain, where they founded the kingdom of Hungary during the tenth century and adopted western Christianity. Khazar power was further reduced by Russian attacks in the 960s (Itil, the capital, fell in 965), and by the emergence of an independent Alan kingdom, which by the 1030s had swallowed up the western half of Khazaria and, with the attacks of the Oguz (or Cumans as the Byzantines also called them) driving the Pechenegs west. By the 1060s the kingdom of the Alans had absorbed also the eastern half. Independent Khazaria disappeared.

The Rus’ first appear in the 830s. Scandinavian raiders and traders, they colonised the Baltic coastline in the mideighth century, before moving inland along the great rivers from the Baltic and down to the Black and Caspian seas. They established a series of riverine principalities at Novgorod, along the Volga, Kiev and, a little later, at Tmutorokan on the Black Sea. Asserting their control over the scattered Slav populations, raiding Byzantine territory in the 830s and 840s, one group - probably from the Volga region - launched a surprise attack on Constantinople in 860. They were brought under a single rule by Oleg of Kiev, successor to the Rurik who had first established a lordship over the Novgorod district, but were initially client tributaries of the Khazars.

Kiev increased in importance partly through the support of the Byzantine empire, which needed a reliable ally in the region to prevent a recurrence of the attack of 860. Trade agreements in the early tenth century, and the baptism of the Russian princess Olga in 960, cemented this alliance. But there were tensions. Olga’s son Svyatoslav remained a pagan, and in a joint attack with the Oguz in 965 destroyed the Khazar Khaganate and brought the Volga Bulgars and Rus’ under his sway. An uneasy modus vivendi existed between Kiev and the Pechenegs. At Roman request, Svyatoslav attacked Bulgaria in 967, but then occupied the whole country. The Byzantine counter-attack forced the Rus’ leader to terms, but he was killed on his return journey to Kiev in a Pecheneg attack. The Byzantines were able to occupy eastern Bulgaria; in Kiev there followed ten years of conflict until the prince Vladimir seized power in 980. Treaties with the empire eventually brought about the conversion of Vladimir and his circle to Byzantine Christianity (in 988: Kiev became an ecclesiastical province of Constantinople, with a metropolitan bishop at Kiev) and the establishment of the Varangian guard, a consequence of the Rus’ promise to furnish troops to the Byzantine emperor when asked to do so. With the increasing threat from the Pechenegs the Rus’ now became key allies of the empire in the south Russian steppe.

This page intentionally left blank

Part Three:

The Later Period (c. 11th-15th Century)

This page intentionally left blank

World History

World History