The mortality from the plague was so great in the late 14th and 15th centuries that death became a predominant theme in medieval art. Representations of death, such as the sarcophagus below the horseman, showed the ravages of decayed bodies. The armies of the dead, clothed in their shrouds, are led by Death, one of the four horsemen of the apocalypse. They easily defeat the living army and march toward a prosperous city.

Francesco de Marco Datini, an Italian merchant from Prato, lived through the best and the worst of the late Middle Ages. He was only a chdd when the Black Death raged through Italy in 1348 and killed his parents. He had a small inheritance and was raised by a woman to whom he referred affectionately as a substitute mother; she signed her letters to him as “your mother in love.” Francesco apprenticed himself to a merchant in Florence and learned to trade. Soon after his 15th birthday, he joined other merchants who were going to the rich papal city of Avignon. He prospered by importing Italian art and luxury items for the cardinals and other wealthy people who lived there. When Datini was more than 40, he returned to Prato and married Margherita, who was 25 years his junior. He was often away, and they exchanged letters weekly. AH of these letters and many others are preserved in his house in Prato. Although he was successful in business, he shared the anxieties of many people in the late Middle Ages about visitations of the plague. When plague was raging in Prato, Datini, Margherita, and his illegitimate daughter set out by mule for Bologna

Onjune 17,1400. One ofhis correspondents wrote from Florence, “I have seen two of my children die in my arms in a few hours.” Datini himself lived another 10 years, dying peacefully in Prato in 1411.

People living during the 14th and 15th centuries often alluded to the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse: famine, disease, war, and death or salvation. In northern Europe a prolonged shift in the weather patterns brought colder and wetter weather, which resulted in poor harvests and severe famines in the early 14th century. Disease, the second horseman, brought the Black Death in 1348, killing offa third to half of the population. War, never a stranger to Europe, took on a new and more deadly form in the late 14th and 15th centuries. Europe had settled down to organized warfare under monarchies. Battles were contained on battlefields and did not do much harm to the local populations. During the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453) between England and France, however, battles were infrequent. The real fighting was a war of attrition, in which France preyed on English shipping and invaded England’s southern coast and English troops marauded the French country-

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse Bring Terror to Europe_

Both ancient Hebrew and Christian literature included texts that dealt with the end of the world. In the New Testament, the book of Revelation is often called the Apocalypse, whereas in the Old Testament the world’s end appears in Isaiah, Ezekiel, Daniel, and other books.

The subject inspired texts full of rich imagery and symbols, among them the Four Horsemen of the

Apocalypse. The meaning of these figures has been widely interpreted. One interpretation holds that the rider of the white horse is Christ, the rider of the red horse is war, the rider of the black horse is famine, and the rider of the pale horse is death and disease.

The significance and meaning of the Bible’s apocalyptic prophesies received considerable attention from both Christian and Jewish writers

During the Middle Ages. Apocalypse 1:1-2 introduces the text: “The revelation of Jesus Christ which God gave him, to make known to his servants the things that must shortly come to pass; and he sent and signified them through his angel to his servant John. . . Blessed is he who reads and those who hear the words of this prophecy, and keep the things that are written therein; for the time is at hand.”

Side, where they destroyed vineyards and plundered livestock, valuables, and crops. The pope was stiU at Avignon, but the papacy was by now completely discredited by its continual search for new sources of money. Many people had begun to question the pope’s authority, and new heresies— such as those of university professors John Wychffe andJanHus—drew followers. With so much going wrong, people thought the end of the world was near.

But these two centuries also brought new ideas, new freedom, new piety, and a comfortable life for many who survived the calamities. Vernacular, as opposed to Latin, literature became popular. Dante Alighieri, Francesco Petrarch, Giovanni Boccaccio, Geoffrey Chaucer, and Christine de Pisan all contributed to the new literature. If the papacy was corrupt, the laity was becoming more pious and more intent on building their own parish churches and ensuring their own salvation. Luxuries of fine cloth, foods, larger homes, books, and art became more available as the population shrank. In the midst of death, therefore, new benefits arose for the living.

Famine devastated the poor of northern Europe during the Great Famine from 1315 to 1317 and again in the early 1320s. Contemporary accounts note that it rained so much in the summer of 1315 that the crops were ruined by the wet weather. The rain continued, making the fields too muddy for planting the winter wheat in the fall and the summer crops in the spring. The harvest was pitiful, and the grain that could be harvested had to be dried in ovens. And the rain continued into 1317. The cattle developed diseases due to the wet weather and lack of grain and died. The poor died of starvation in lanes and fields in the country and in alleys in the cities. Prisoners tore apart and ate new inmates who were put into their jails. At a distribution of alms in London, 60 men, women, and children were crushed to death as the crowd pushed forward to get pennies for food. Charities had no surplus food to distribute because crops grown at monasteries were also mined. Importation offood in large quantities from southern Europe was not feasible. When the king of England sought such relief, pirates boarded the ships before they could reach port. The population had no sooner recovered than another famine hit m 1323.

The pope, comfortably resident in Avignon, suffered none of the deprivation of the faithful of northern Europe. Rome was in the hands of hostile families who engaged in fighting each other and opposing any candidate for pope that the other side proposed. Over time the popes purchased the town of Avignon (located in what is now southern France), which was surrounded by vineyards, orchards, and grain fields. They built a magnificent palace that still stands, and the cardinals built palaces for themselves in the town and surrounding countryside. The churchmen became patrons of artisans, artists, and writers, who were flourishing in the late 14th and 15th centuries. But the Avignon popes had some serious problems. They had the difficult task of defending their position as successors ofSt. Peter, founder ofthe Church of Rome, while Hving outside that city and never visiting it. They also had financial woes. AH of the estates that Pope Gregory the Great had spent so much time organizing and administering and that subsequent

Popes had defended against such powerful monarchs as Frederick I and II were now in the hands of various factions, none ofwhich wanted to contribute the usual amount to support the papacy. The papacy therefore had to look elsewhere for money. The pope had lost much of his power to tax the clergy because of fights with Edward I and Philip IV, so the papal courts became even more rapacious in collecting fines for divorces and annulments of marriages, and the popes sold bishoprics to the highest bidder. They also began an aggressive policy of selling indulgences, or the forgiveness of particular sins. Finally, they began to sell a plenary indulgence, which would forgive sins not yet committed. The theological presumption was that the sacrifice o0esus at his crucifixion and the suffering of martyred saints had created a reservoir of goodness, similar to a bank deposit, that the faithful could draw upon for a price and avoid the torments of heU. The Franciscans and Dominicans participated in selling indulgences, thus alienating themselves from the inspiration of their founders. The orders had become so corrupt that they were little more than fimd-raisers for themselves and the papacy. Other clergy were also willing to enter into money-making schemes for personal enrichment.

The lay response to churchmen using the money they raised to fund their own opulent lifestyles was twofold. Criticism of the lavish living mounted among the faithful, but some flocked to the papal court as purveyors of fine merchandise or as suitors for papal patronage. The correspondence of Francesco de Marco Datini provides an accurate picture of the luxury market and the opportunities it presented to shrewd businessmen. His orders to his partners in Italy included “a panel of Our Lady on a background of fine gold with two doors, and a pedestal with ornaments and leaves, handsome and the wood well carved, making a fine show, with good and handsome figures by the best painter, with many figures.” He was more of a merchant than an art critic, for he added, “Let there be in the center Our Lord on the Cross, or Our Lady, whomsoever you find—I care not, so that the figures be handsome and large, and best and finest you can purvey.”

Others, such as Francesco Petrarch (1304—1374), came to sell their poetry and writing rather than goods. The son of a Florentine notary, Petrarch studied law at Montpellier and Bologna and then took holy orders, moving to Avignon. Putting aside his vocation as a priest, he wrote a series of love sonnets in Italian to a woman named Laura, who died in 1348, the plague year. Denied the patronage that he sought from Avignon, he became a severe critic of the town. He wrote that Avignon was a “fountain of anguish, the dwelling-place of

The Burgundian court played a leading role in politics and in setting aristocratic style in the 13th century. The marriage of Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy to Isabel of Portugal in 1430 was an occasion to display beautiful dress and fine foods. The wedding party was held outdoors and men and women even brought their falcons with them.

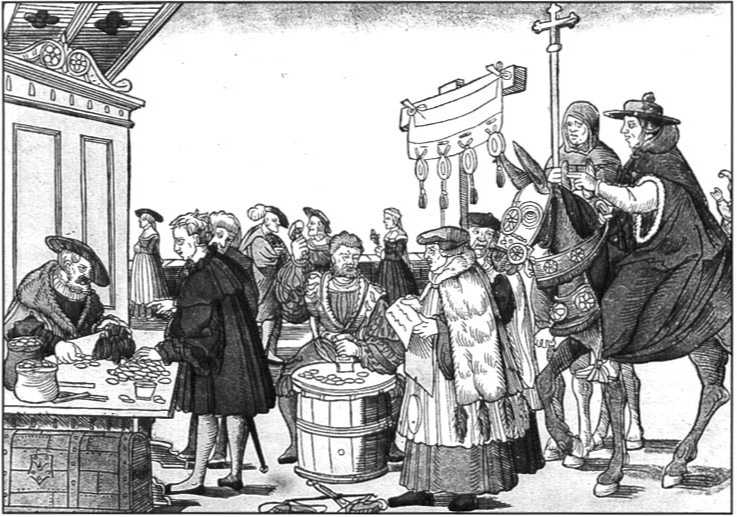

Separated from Rome and its regular income, the Avignon papacy began to sell indulgences, or forgiveness of sins. The assumption was that the sacrifice of Christ and the saints had built up a reservoir of salvation which the Church could dispense by selling it to the laity. One could buy forgiveness for a specific sin or get a plenary indulgence that would cover all possible sins. Even when the Church returned to Rome, it continued to sell indulgences, as this woodcut from the early 16th century indicates.

Wrath, the school of errors, the temple of heresy, once Rome, now the false guilt-laden Babylon, the forge of lies, the horrible prison, the hell on earth.”

Edward I of England and Philip IV of France had challenged the pope and taxed the clergy in order to carry on their political stmggles against each other. Edward, of course, wanted to get back the French territory that John I had lost a century earlier, and Philip wanted to take from Edward the territory he stiU held in southern France. The two monarchs, however, did not engage in active warfare and, finally, Edward married his son, the future Edward II, to Isabelle, daughter of Philip.

War between the two countries did not break out until the reign of their son, Edward III (1327—1377). Edward Ill’s ascent to the ¦ throne was surrounded by drama. Flis mother had taken him to France to pay homage to the French king for the English territory in France. Traveling with young Edward and his mother was the English baron Roger Mortimer. The three of them made a plan to overthrow Edward II. Young Edward married the daughter of the count of Fiainault, and, as a dowry, she brought military help for the invasion of England. Isabelle and Mortimer returned to England and had Edward II killed after a humiliating captivity. With the support of Parliament, they declared Edward III king and themselves as his regents. But Edward III was an energetic young man. Collecting a band of knights, he seized Isabelle and hunted down her lover in their bedchamber. Fie had Mortimer executed, but confined his mother to a comfortable royal castle far from the political scene.

Edward III embodied the ideals of medieval kingship. He was young, chivalrous, intelligent, and an excellent warrior. He fought in tournaments, sometimes anonymously, and he reestablished King Arthur’s Round Table and a chivalric order, a group of nobles and knights selected by the king, called the Knights of the Garter. His love of warfare led him to pursue aggressive relations with France. The excuse for beginning what became known as the Hundred Years’ War was that the Capetian line had failed to produce a male heir. Philip IV’s sons inherited in succession, but they did not have male children. This meant that Edward, as the grandson of Philip through his mother, had a claim to the French throne. The French could not allow their ancient rival to take over the throne of France, so they selected another branch of the Capetian family, the

As a younjj man, Edward III of England paid homage to Philip IV of France for fiefs he held in France as a vassal of the French King. Edward wears a robe with the rampant lions symbolic of the English king, and Philip wears a robe with the fleur-de-lis that was the symbol of France.

Valois. Nonetheless, Edward made himself a new coat of arms by combining his arms (the rampant lions) with the lilies of France (fleurs de lys) and declared himself king of France as well as England.

Another dispute that led to the war involved the county of Flanders (part of modem Belgium), which the French kings claimed belonged to France. Flanders was one of the wealthiest cloth-manufacturing centers of Europe. Fine woolen cloth and tapestries were woven and dyed there by wage laborers who worked on heavy looms. The wool for the cloth came mainly from England, so the Flemish economy was dependent on English wool. Edward saw a way to get at the French by stirring up trouble in Flanders. He encouraged the Flemish weavers to revolt by withholding the EngHsh wool from their markets. The embargo worked, and the Flemish weavers sided with the English against the French. With trouble brewing in Flanders, Edward launched his first campaigns.

World History

World History