After the death of Geiseric in 477, the Vandals lost their central role on the Mediterranean stage. The cessation of widespread raiding after the peace settlement of 476 meant that the Vandals appeared rather less within the written sources. Odoacer’s rise to power in the same year and the final disappearance of the western imperial court closed an important theatre for political intrigue, but Huneric’s apparent distaste for the political posturing which had so served his father was also partly responsible for the eclipse of Vandal power. Shortly after his accession to the throne, Huneric sent an embassy to Constantinople which formally withdrew the last Vandal claims over the patrimony of Valentinian III, and accepted the appointment of a Catholic archbishop in Carthage.95 Embassies continued to shuttle between Constantinople and the Vandal kingdom throughout the 470s and 480s, but the diplomatic brinksman-ship of Geiseric was no more.96 The historian Malchus argues that this diplomatic retreat was evidence of a gradual deterioration in the martial spirit of the Vandals - a concept that was to prove popular among later Byzantine historians.97 But the Vandals had not become cowards overnight. With Geiseric’s death and the political upheaval of the Italian peninsula came a profound reassessment of the Vandal role within the wider world. If the first half of the Vandal century had been marked by attempts to find a place within the collapsing political world of the fading western empire, the 50 years which followed Geiseric’s death were defined by the defence of the Vandal kingdom at home, and the maintenance of the political position abroad.

The African frontier

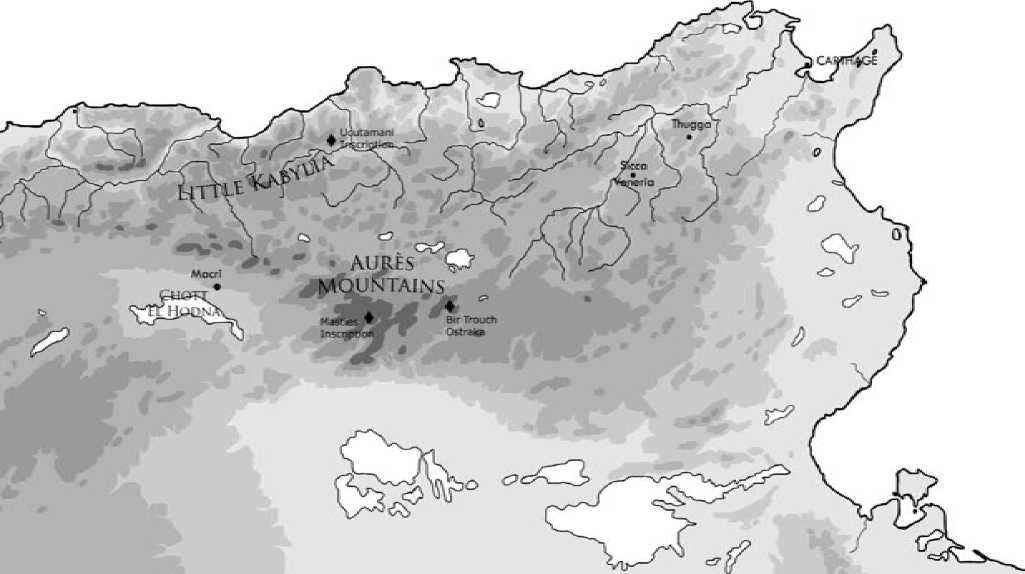

From the 480s, the Vandals had to pursue an active external policy within Africa as well as in the wider world. The ominous emergence of several Moorish power blocs on the southern frontier of the kingdom restricted the freedom of the later Hasding kings to dominate the Mediterranean as Geiseric once had. Crucially, this threat was not created by the sudden appearance of new peoples on the African frontier, nor by the rampages of desert nomads attacking settled communities. Instead, these Moorish polities are best regarded as local responses to the political vacuum left by the gradual disintegration of imperial power in the frontier regions.98 As the Roman empire progressively retreated from the African interior, from the early fourth century to the effective cessation of imperial authority in 455, local elites became increasingly powerful. Very similar processes took place among the local military aristocracies of the Basque country, Brittany or upland Britain, but the sheer size of the African frontier zone meant that the Moorish successor states were both many and varied. In some cases, as with the Garamantes in the Libyan desert, or the Arzuges in the south of Mauretania Caesariensis, these kingdoms developed with relatively little direct contact with the Hasding kingdom of Carthage. In the south of Byzacena and Numidia, however, and in the upland regions of the Aures massif, these local military aristocracies represented a direct challenge to Vandal authority.

Geiseric managed this situation well, and effectively precluded any substantial challenge to Vandal authority in the south of his kingdom. He did this in part by establishing his own position as the principal arbiter of imperial authority to the south: where local elites had once relied upon Rome or Ravenna for the ranks and titles that legitimated their authority, they increasingly turned to Carthage.99 In this, Geiseric was doubtless helped by the fact that his own vigorous military policies not only discouraged revolt, but also allowed his neighbours the opportunity for fruitful alliance with the Hasding regime.100 Writers like Victor and Sidonius Apollinaris note the enthusiasm with which the Moors joined in the Vandal plundering expeditions throughout the Mediterranean, and this cannot all be put down to rhetorical embellish-ment.101 The ideological pre-eminence of Carthage within Africa did not disappear entirely with Geiseric’s death, and Procopius refers to formal Hasding patronage of some Moorish polities as late as the reign of Hilderic (and perhaps even Gelimer). But this authority was not what it had been in the early years of the Vandal kingdom. From the 480s onwards, the balance of power had begun to shift. Like the Hasding kingdom, the Moorish states grew and changed over time. When Huneric ascended to the throne in 477, therefore, he was not only acting without his father’s enviable reputation, he was also dealing with

Figure 5.1 The Vandals and the Moors

Moorish polities which had benefited from an additional three or four decades of semi-autonomous development.

Procopius states that the first troubles occurred in the Aures Mountains towards the end of Huneric’s reign. This region had been a keystone of the frontier and like many regions of Africa had become thoroughly Christianized.102 It seems to have passed under Vandal authority with the treaty of 442, but the reasons for its subsequent secession are not immediately clear.103 Procopius simply states that Huneric lost control of the mountains towards the end of his reign, and that the Vandals never recovered them.104 This is likely to have been true - certainly it would have taken a concerted campaign to bring the highlands themselves back into the kingdom, and we know of no such expedition. Nevertheless, the distinctive Vandal system of dating is employed on the Bir Trouch ostraka, which were found in the eastern foothills of the same range, and which date from the reign of Gunthamund. It seems likely, therefore, that while effective control may have been lost over the Aures uplands, Vandal authority remained recognized in the lowlands, and this may have continued down to the Byzantine period.105

A Latin inscription found in the middle of the Aures massif casts some light upon the changing political circumstances of the 470s and 480s. The text was erected in honour of the Moorish leader, Masties, probably in the late fifth century:

I, Masties, duke [dux] for 67 years and emperor [imperator] for 10 years, never perjured myself nor broke faith with either the Romans or the Moors, and was prepared in both war and in peace, and my deeds were such that God supported me well.106

The inscription is undated, but the text does hint at a major political change that took place during Masties’ lifetime.107 Clearly, Masties was a dux for most of his adult life, a term which is best regarded as a Latin rendering of an indigenous political title. Masties, in other words, was the head of a group of Moors for more than half a century. Ten years before his death, however, he assumed the title of imperator, a bold claim of political authority which strongly implies that he recognized no other external power. It has recently been suggested that this sudden claim to power probably coincided with the Aures revolt of ad 483-4. This would imply that Masties was first made dux in around 426 and died in 494, presumably in his eighties. The strong Christian overtones of the inscription hint that Masties’ break from Vandal authority may well have been prompted by the onset of Huneric’s persecution. Faced with these horrors, the formerly loyal lieutenant in the south of Numidia revolted from the Vandals and permanently removed his territory from the control of the Arian Hasdings.

The inscription was presented in the political language of the old empire, in a world where this clearly continued to mean something. Masties’ had been a dux and an imperator, and his successor chose to celebrate this service in the very traditional form of a Latin inscription. But the sentiments of the epitaph are not wholly classical, and declarations of hybrid political authority are found on other Latin inscriptions elsewhere along the African frontier. Around the same time as Masties was honoured for his fidelity to both Romans and Moors (Mauri), an inscription in Altava, to the far west of North Africa, commemorated the construction of a fort in the kingdom of Masuna, the ‘King of the Moors and the Romans’.108 A fragmentary and undated inscription found at the eastern end of the Little Kabylia has obvious similarities. This text refers to the rex gentis ucutaman[orum] (‘King of the Ucutamani Peoples’), and was set up as a Christian epitaph after the king’s death.109 Like the inhabitants of the Aures, the Moors of Kabylie had experienced an uneasy relationship with Roman imperial power. Nevertheless, it is conspicuous that when this unnamed king was commemorated it was in Latin and in a formal inscription. The political and cultural environment in which all of these polities developed was not identical to that which nurtured the Vandals in Carthage, but nor was it so very different. In both cases, military power was celebrated and legitimated through traditional channels.

Huneric enjoyed rather better relations with the Moorish leaders who ruled along other stretches of his frontier. Victor of Vita describes how the first Nicene exiles of his reign were sent out from Carthage and were handed over to Moorish soldiers on the main road into Numidia, and were escorted into the distant reaches of that province.110 These may well be the same exiles whom Victor of Tunnuna places in Tubunae, Macri and Nippis in the area around Chott El-Hodna.111 Geiseric had adopted a similar policy in concert with the Moorish king Capsur, whose kingdom ‘Caprapicta’ has been variously located by scholars in the far south of Byzacena or on the southern frontier of Numidia and Mauretania Sitifiensis.112 In each case, the involvement of the Moorish rulers in the punishment of the enemies of the Vandals testifies to the close relations between the different powers. The fact that this continued under Huneric highlights the complexity and delicacy of diplomacy at the frontier.

As the authority of the different Moorish rulers rose along the frontiers, so that of the Hasding kings fell. It is difficult to chart this process in detail, but occasional references in the textual sources testify to a level of unrest in the countryside. Procopius states that Gunthamund fought numerous campaigns against the Moors but does not elaborate.113 The same writer provides a rather fuller narrative of Thrasamund’s campaign against the Moorish ruler Cabaon in Tripolitana. Procopius’ account suggests that the Moors went out of their way to win the support of the provincial Romans, which may testify to expansionist ambitions on the part of Cabaon, but the causes of the conflict are not made clear.114 A general atmosphere of instability is further suggested by allusions to ‘barbarian’ violence in the Life of Fulgentius, although it is never clear where references to general rural banditry stop and where those to genuine political conflict begin.115 Certainly, this conflict does not seem to have been sufficiently serious to interrupt production, and left little mark on the archaeological record before the third decade of the sixth century.

By the reign of Hilderic, however, this conflict escalated substantially. Procopius refers to extensive campaigning in Byzacena during the 520s, and Corippus alludes to a series of Moorish uprisings all along the frontier.116 Certainly, the Hasding princes Hoamer and Gelimer both won their spurs in fighting against the Moors, and the Byzantine writers commonly assumed that the Vandal military resented Hilderic’s poor performance on the battlefield.117 Precisely what caused these new tensions is unclear. It is only following the Byzantine conquest - when the empire of the east found that the Moorish polities would not be so easily overcome as they had originally imagined - that the military history of this region can be written in any detail. Nevertheless, it seems clear that by the reigns of Hilderic and Gelimer, the African frontier had grown to dominate the external policies of the kings of Carthage.

Sicily

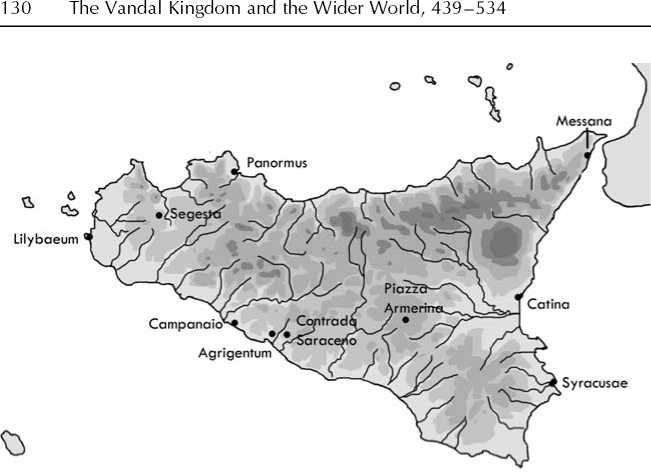

Sicily was the most important of the Vandal overseas territories, for economic and strategic reasons, and came to dominate Hasding Mediterranean policy in the last half-century of the kingdom. As with many other regions in the Mediterranean, Sicily changed dramatically in the fourth, fifth and sixth centuries, both in the towns and in the countryside. For much of the early imperial period, the island had been celebrated for its extraordinary fertility, but the comparable wealth of Africa and Egypt meant that it had rarely been intensively exploited.118 The great senatorial landholders of Rome maintained villas there, but chiefly seem to have used them as places for retreat and pleasure, rather than as centres of production. With the foundation of Constantinople in the early fourth century, however, and the redirection of Egyptian grain to the new eastern

Figure 5.2 Vandal Sicily

Capital, Sicily once more took up the burden of feeding Rome. As the rebellions of the fourth century made African supply routes less reliable than they had been previously, and particularly after the events of 439 took Carthage and its rich hinterlands permanently out of the hands of the western empire, Sicily became a crucial mainstay of the imperial economy.

The presence of this rich island so close to Africa inevitably drew the attention of the Vandal kings. As early as 437, barbarian pirates had harassed the coast of Sicily, and it was no surprise that one of Geiseric’s first actions after the capture of Carthage was to attack Lilybaeum and Panormus.119 But the Hasdings struggled to establish their authority over the island. In the treaty of 442, Sicily remained in imperial hands and, even after the invasion of 455, the Vandals were far from secure.120 Ricimer defeated a Vandal fleet at Agrigentum in 456, and in 460 and 468 Count Marcellinus twice re-established Roman power in concert with the grand imperial campaigns against Carthage.

This period of conflict left less of a mark on the archaeology of Sicily than might be expected. The relative scarcity of well-excavated urban sites within Sicily makes generalization about the state of the island’s towns difficult, but the fragmented image which does emerge is scarcely one of crisis, and was certainly not one of panic.121 Few towns in the

Island seem to have been fortified, in striking contrast to southern Italy, and imperial investment in the defence of the island would appear to have been sparing. In Marsala, the ancient defences, erected during the Hellenistic period, never seem to have been repaired, despite abundant evidence for Vandal attacks between 440 and 475. At Agrigentum, such defences that were put up were only ever temporary. It is possible - even probable - that traces of ‘Byzantine’ defences in the other cities of the island have been misdated, and may have been erected in the fourth or fifth century, but it seems unlikely that there was a concerted programme of fortification in response to the Vandal threat.122 At Catania, for example, the wall circuit was only restored during the Ostrogothic period, and even then as a local operation.123 Yet despite this, Sicily seems to have survived this prolonged period of conflict relatively well. An imperial tax remission from the mid-440s suggests that productivity was interrupted by the earliest Vandal attacks, and several small settlements were destroyed or abandoned in the middle of the fifth century, but in the medium term Sicily seems to have remained surprisingly healthy.124 The preserved estate records of one Lauricius from ad 445/6 attest to continuity of landholding even during a period of particular difficulty, and the literary sources all attest to the wealth of Sicily in this period, even after the Vandal attacks.125

We hear nothing else of Sicily in the historical record until 476, when the Vandals formally ceded their authority over the island. According to Victor, Geiseric reached an agreement with Odoacer in that year, which surrendered the island in return for an annual tribute:

One of these islands, namely Sicily, [Geiseric] later conceded to Odovacer, the king of Italy, by tributary right. At fixed times, Odovacer paid tribute to the Vandals, as to his lords; nevertheless, they kept back some part of the island for themselves.126

The most convincing explanation for this peculiar agreement is that Geiseric sought to consolidate the position of the Vandal kingdom in the months before his death.127 Sicily had long been a bone of contention between Carthage and the ruling powers in Italy, and the Vandal king may have wished to spare his successor such difficulties. Realising that Odoacer might later have been in a position to take the island by force, Geiseric may simply have decided to gain the best possible deal for a territory which the Vandals could not hope to hold in perpetuity. The treaty with Zeno would have reassured the Hasdings that the period of the great imperial expeditions against Carthage was probably in the past, but by retaining his claim over a part of the island Geiseric retained a strategic foothold. Victor does not state precisely where the Vandal pars of Sicily was located, but it can only have been the promontory of Lilybaeum - the closest point to the African mainland and a long-standing strategic objective of the Vandal state.128

The treaty of 476 did not end Vandal interest in Sicily. In 489, the magister militum Theoderic began his conquest of Italy and founded the Ostrogothic kingdom. While Theoderic and Odoacer were occupied in the north, Gunthamund turned his attention to Sicily. The only source for this campaign is an allusion in a contemporary African poem to recent Vandal ‘triumphs of land and sea’. The poem names one ‘Ansila’ as among those present at the victory celebrations, and it is commonly assumed that he was an Ostrogothic general, defeated in an otherwise forgotten Sicilian campaign.129 Cassiodorus’ Chronicle states that the Vandals stopped their attacks on Sicily in ad 491, which implies both that attacks had been taking place before this date, and that a peace treaty was reached in that year.130 The details of this treaty are unknown, but a fragmentary inscription (which has been lost) alludes to the boundary between the Vandals and the Goths and may indicate that a formal territorial division was invoked at this time.131 Regardless of its form, the peace seems to have held until the end of the century.

In ad 500 the wedding of Thrasamund with the Ostrogothic princess Amalafrida formalized the diplomatic relations between the Vandals and the new rulers of Italy. Procopius is our principal source on the wedding, which was the second great dynastic union in Vandal history:

Wishing to establish his kingdom as securely as possible, he [Thrasamund] sent to Theoderic king of the Goths, asking him to give him his sister Amalafrida to wife, for her husband had just died. And Theoderic sent him not only his sister but also a thousand of the notable Goths as a bodyguard, who were followed by a host of attendants amounting to about five thousand fighting men. And Theoderic presented his sister with one of the promontories of Sicily, which are three in number - the one which they call Lilybaeum - and as a result of this Thrasamund was accounted the strongest and most powerful of all those who had ruled over the Vandals.132

The marriage was a momentous political event. In Ravenna, poets and courtiers boasted of the new Ostrogothic ascendancy. Ennodius celebrated the ‘obedience’ of the Vandals to Theoderic’s rule in his famous panegyric of ad 507, and in the same year Cassiodorus implied that the great enemy of Italy had been brought to heel by Gothic diplomacy.133

Nor can the Vandals have missed the political posturing that accompanied the wedding. The granting of Lilybaeum as a wedding gift, in particular, offered a concession to the Vandals, but also asserted Ostro-gothic suzerainty over the island as a whole: Lilybaeum, it was implied, was theirs to give.

The marriage of ad 500 was probably more of an alliance between equals than an assertion of Ostrogothic hegemony. Jordanes did not see the wedding as a triumph of Gothic power, despite his long-standing disdain for the Vandals, and Procopius states explicitly that Thrasamund’s wedding made him the most powerful of all the Hasding kings.134 In normal circumstances Amalafrida’s huge Gothic escort might well have represented a pointed show of force, but Thrasamund was at war with several Moorish kingdoms at the time of the wedding, and Theoderic’s troops may simply have been military aid for a fellow monarch - and now brother-in-law - who was in difficulty.135 This is not to suggest that the provision of military support was entirely without political overtones, but Thrasamund, as an ally of the eastern court and the possessor of a large navy, was not quite ready to adopt the position of vassal king to the new ruler of Italy.136

For the remainder of his reign, Thrasamund proved inconsistent in his dealings with the Ostrogoths. The extant sources have rather more to say about Ostrogothic activities in this period than they do about the kingdom of Carthage. When the Vandals do drift into focus, it can be seen that Thrasamund clearly acted in his own self interest, rather than as a vassal or even as a warmly supportive ally. In ad 507 or 508, the Byzantine fleet attacked Italy by sea, just as the Vandals had once done.137 If the Ostrogoths expected their allies to help, they were to be sorely disappointed, and the Hasding fleet remained in Carthage. In 510, Theoderic’s interventionism in the Visigothic kingdom of Toulouse led to the disgrace and expulsion of the pretender Gesalic. In defiance of Theoderic’s policies, Thrasamund offered sanctuary to the exile, and eventually surrendered him only after some delicate diplomatic negotiation from Ravenna and then only to prevent the escalation of the situation into a major incident.138

This uneasy peace was not to last. After the accession of Hilderic in 523, the Vandal kingdom was strongly linked to Constantinople, and the relationship with the Ostrogoths deteriorated seriously. Amalafrida survived her husband, but was imprisoned shortly after Thrasamund’s death on suspicion of treason, along with the remaining Goths in her retinue.139 By 526, she had been put to death.140 In all likelihood, this provocative act simply reflected the general shift in Vandal diplomacy, away from the Gothic court at Ravenna and towards the Constantinople of Justin and Justinian. Indeed, from 523, the court atmosphere at both Carthage and Ravenna seems to have changed. In Carthage, the homecoming of prominent Catholics brought to prominence men like Fulgentius, who had spent their years in exile fostering valuable links with the clerics of Rome and Italy.141 In Ravenna, Theoderic’s domestic policy became increasingly intransigent towards Byzantine sympathizers, a trend which resulted most famously in the imprisonment and later execution of Symmachus and Boethius, but which also led to the increased marginalization of prominent Roman Catholics.142 As Theoderic distanced himself from the imperial capital, Hilderic found himself forced into choosing sides between the Ostrogoths to the north and his own particular sympathizers in the eastern empire. If Amalafrida had kept Thrasamund more or less in the Ostrogothic party, no such ties bound his successor; Hilderic turned to Constantinople.

One peculiar result of this change in diplomatic allegiances was Theoderic’s ambitious decision to assemble his own fleet in 525/6 ad, a project that may be traced through the various letters of Cassiodorus’ Variae.143 This represented a direct challenge to the naval mastery of Carthage and Constantinople, and a symbolic defence of Gothic interests at sea and along the coasts. As Theoderic himself put it: ‘there is no reason for the Greek to fasten a quarrel upon us, or the African to insult us.’144 Quite whether the assembly of the fleet was the prelude for a still bolder military operation is unclear, but Cassiodorus’ letters do testify both to the enormous logistical capacity of the Gothic state, and to the king’s anxiety that the fleet be ready, manned and paid for at Ravenna in June 526.145 Quite what Theoderic might have accomplished with this fleet can only be speculated; he died on August 30 of the same year. Despite the late tensions between Theoderic and Hilderic, and Athalaric’s later protests over the execution of Amalafrida, however, relations between the Ostrogoths and the Vandals were generally good. Sicily was at the heart of this detente.

Sardinia

Sardinia provides a different image of Vandal imperialism, but during the first 20 years of this period, its history closely paralleled that of Sicily.146 Like Sicily, Sardinia only passed under the full authority of the Vandal crown towards the end of Geiseric’s reign. Raids in the early 440s did not last, and the island remained an imperial possession after 442. The island was among the regions which were occupied in 455, but a defeat of the Vandal fleet off Corsica in the following year suggests that

Figure 5.3 Vandal Corsica and Sardinia the western empire did its best to resist this expansion. Sardinia was recaptured by Marcellinus at some time between 466 and 468, but came back under Vandal control during the following decade, and must have been among the territories permanently ceded to Geiseric in the treaty of 476.

Like Sicily, Sardinia was celebrated in antiquity for its fertility. Palladius is emphatic in his praise of the island, and the rich plains in the hinterland of Neapolis are among the most fertile regions in the Mediterranean.147 Documentary and archaeological evidence for the exploitation of the landscape is more sparing for Sardinia than it is for Sicily, but once again broad patterns of continuity throughout the Vandal period are evident. The towns of Caralis, Cornus, Turris Lisbonis and Neapolis all changed over the course of the fifth century, but these developments - typically the abandonment of some areas of occupation and the evolution of new centres of urban life - may be witnessed throughout the western Mediterranean in this period.148 The material record also testifies to intensive mercantile contact between Sicily, Sardinia and North Africa, and if textual evidence occasionally hints at interruptions in shipping, these seem to have been the exception, rather than the rule.149

Where Sardinia differed from Sicily, however, was in its position as a more or less permanent Vandal territory.150 Less politically contested than Sicily, Sardinia remained under the nominal rule of Carthage until the Byzantine reconquest of 533. Vandal rule of the island probably followed imperial precedent; certainly there is little evident that the Hasdings introduced substantial administrative changes. Late imperial power in Sardinia had been entrusted to a praeses, an official who combined military, judicial and civil governmental functions. The Vandals may have granted some degree of effective autonomy to the governors of Sardinia, if only for practical reasons, and it is not impossible that the ruler of the island was largely left to his own devices in return for an annual tribute to Carthage.151 Whatever the arrangement, it seems likely that the praeses of the fifth century issued coins on his own authority.

The only Vandal governor about whom any information survives is Godas, a Gothic soldier and the last representative of Hasding rule within Sardinia, and his administration was exceptional.152 Sent there by Gelimer following his usurpation in 531, Godas was charged with securing the loyalty of Sardinia and its troops, a responsibility that he shirked in spectacular fashion. Recognizing the imminent danger of Justinian’s reconquest, Godas declared his intention to break from Vandal authority and requested military support for this coup from the eastern emperor. Justinian received this embassy warmly and offered military support, but rejected Godas’ demand to be afforded royal status as the ruler of Sardinia in his own right. The emperor promised troops to the rebel, but proposed to send them under the command of a general loyal to Constantinople. In Carthage, Gelimer got wind of this plot and crushed the rebellion at source, sending Stotzas - a rather more trustworthy ally - to put down the revolt. In the event, Stotzas was successful, but the large expeditionary force within Sardinia critically weakened the defences of Africa itself.

Godas’ period of office was unusual, but the episode does cast some light upon the nature of the Vandal administration of Sardinia. First, and most obvious, is the fact that the island was an important part of the kingdom, and yet apparently enjoyed some autonomy from Carthage by virtue of its geographical position. Gelimer felt it important enough to send Godas to establish his authority there, presumably in order to prevent rebellion. When Godas revolted in turn, Gelimer suppressed the rising with considerable force, even at the cost of losing the city of Tripolis, which was also in revolt, and ultimately Africa itself. Sardinia, then, was an important component of the Vandal ‘empire’.

Godas’ appointment and later rebellion also highlight the military nature of the Vandal presence in Sardinia. Although Godas’ appeal to Constantinople suggests that the garrison in the island was relatively small, there clearly was a permanent military presence on the island. This might have been intended to defend Sardinia from other colonizing powers, but the island was rarely contested after the departure of Marcellinus in 468, and intensive Vandal occupation probably only took place after the major treaties with Zeno and Odoacer secured a lasting peace within the western Mediterranean. The garrison was probably intended to provide security from occasional banditry and unrest in the central highlands. The Roman occupation of the island had proved similarly troubled, and the Byzantines were later to suffer from the bandits and rebels they termed barbaricini. The Vandals probably faced very similar problems.153

Among the barbaricini who resisted Byzantine occupation in the 530s and 540s were a group of Moors, probably hidden in the mountains to the south-west of the island.154 According to Procopius, these Moors had been sent into exile in Sardinia following a rebellion against the Vandals in Africa, but this scarcely seems credible. The Moors had been sent to settle Sardinia with their families, and apparently as a coherent group, both factors which suggest a conscious policy of garrisoning, rather than an ad hoc process of exile. Other Byzantine sources of the period confirm that the Moors were included among the Vandal army which occupied the island.155 Given this, it seems likely that the rebels who resisted the Byzantine occupation had originally settled peacefully in the island, either as colonizers or as a military garrison, and had revolted, probably at the time of the invasion from Constantinople. It is impossible to say whether the Moors and Vandals had been settled as distinct groups within the island. One coin minted in the later fifth century bears a monogram that has been read as the mark of a presidia Maurorum Sardiniae, which would suggest both that the Moors were a consciously established part of the Sardinian garrison and that they may have been organized independently from their Vandal allies.156

The Vandal occupation of Sardinia had a dramatic effect upon the development of the church within the island. From around ad 482,

Sardinia became the principal place of exile for Catholic bishops and clerics, and thereafter the islands of the Mediterranean supplanted the Moorish kingdoms as the preferred destination for the turbulent priests of Africa.157 From the early years of Thrasamund’s reign, when the Catholic clergy were expelled from dioceses and parishes even beyond Zeugitana, the Sardinian capital of Cagliari became the focal point of the African Church in exile. Through the extensive correspondence, sermons and scriptural commentaries of Fulgentius of Ruspe, Ferrandus’ Life of the Saint and the constantly expanding corpus of archaeological material, it is possible to appreciate the vibrancy of Christian life in the island at that time.158

The years of African exile represented the first great period of Christian evangelism within the Sardinia. The island had, of course, received missionaries before: bishops from Cagliari, Cornus, Forum Traiani, Sulci and Turris Libisonis had attended the African Church council convened by Huneric in February 484, and Sardinia retained metropolitan jurisdiction over the three dioceses in the Balearic Islands which were also represented in Carthage. Church foundations and Christian catacombs are also known from Sardinia from the fourth century. But the number, wealth and cosmopolitan connections of the African churchmen witnessed an extraordinary expansion in Christian building and had a galvanizing effect upon the church.159 The monastic foundations of Fulgentius, the widespread adoption of Augustinian theology, the popularity of African martyr cults and liturgy and the systematic and precocious expansion of the church into the interior were all brought about by the religious refugees.160 Sardinia created two popes during the Vandal period. Of these Hilarius, who held office from ad 461-468, largely succeeded in spite of the barbarian presence around his island, but his successor, Symmachus (ad 496-514), was doubtless helped by the sudden prominence of the Christian life in Sardinia.

This is a paradox that deserves some attention. As Huneric and Thrasamund sent Catholic bishops to Sardinia, so the church in the island flourished. No less importantly, a province of the Vandal realm chosen for its very isolation as a place of exile was drawn into the cultural and intellectual orbit of the wider Mediterranean world by this very programme of expulsion. There was constant communication between Cagliari and Carthage generated through the passage of secular and clerical exiles.161 Fulgentius himself had made religious journeys to both Sicily and Sardinia long before his own exile from Byzacena, and such pilgrimages may not have been unusual.162 The same bishop’s correspondence testifies to the extensive contact between the bishops and their compatriots, both for spiritual and secular reasons. Simultaneously, the Sardinian exiles fostered increasingly close links with the papacy and the Catholic aristocracy of Rome, a cultural bond that may well have had fundamental implications for the balance of power in the Mediterranean when the clerics were eventually recalled.163 Content as Fulgentius might have been to bewail his isolation in a forgotten corner of the Vandal kingdom, the bishop could make his voice heard by both the pope and the Vandal king when it was necessary.

Corsica and the Balearics

Like Sicily and Sardinia, Corsica and the Balearic Islands only came under Vandal control after 455. Frustratingly, these smaller islands are mentioned only very briefly in the textual sources. It may be that the Balearics were only occupied in 460, as a result of the Vandal expedition against Majorian, but this cannot be stated definitively. The scale of the Vandal occupation throughout the islands is entirely unknown, but in the absence of evidence to the contrary it seems likely that there was some level of administrative continuity in Corsica and the Balearics just as there was in Sardinia.164 Where archaeology of secular settlement patterns exists - it is virtually absent in the Balearics and limited in this period of Corsican history to the inland rural site at Castellu in Haute Corse - there is strong evidence for continuity throughout the Vandal period and even down to the Lombard occupation of the later sixth century.165 As was the case in Sardinia, the expansion of imperial authority over these islands had been slow. In Corsica, the Byzantine forces under Cyril met some resistance, although little is known of the form that this took.166 Belisarius took no such chances with the Balearics and entrusted their control to Apollinarius, an Italian who had been a trusted functionary of Hilderic before Gelimer’s coup led him to lend his support to the imperial reconquest. This precaution proved wise, and the islands were retaken by the empire without difficulty.167

Corsica comes into better focus when viewed through its Christian past. The island did not send any representatives to the Council of Carthage in 484, but some exiles are known to have been sent to the island before that date, and in the wake of the conference 46 more bishops joined them.168 Where Fulgentius provides a positive voice for the exiles of Sardinia, however, the exiles of Corsica are represented only by two mournful poems of exile in the Latin Anthology:

No bread, no drawn water, no distant flame;

These two things alone: the exiled one and his exile.169

Yet the conventions of poetic lamentation should not disguise the vibrant Christian culture that the exiles brought to the island. Those who died in exile, including Appianu of Sagona and Firenzu, were venerated in the island.170 Those who survived left their mark in other ways: the cults of the third-century African martyrs Julia and Restituta were introduced by those sent into exile by the Vandals, and remained even after their departure.

The impact of the Christian exiles is most visible in the Christian architecture of Corsica. The whole early Christian complex at Mariana, the church of S. Appianu at Sagona and that of S. Amanza at Bonifaziu all date from the late fifth or early sixth century, and the early Christian cult site of Pianottoli-Caldarellu was substantially reworked in the same period.171 Christianity also appears for the first time in rural contexts during the Vandal occupation.172 As was the case in Sardinia, the Vandal exiles drew Corsica back into the deeper currents of Mediterranean cultural life. And here too, the departure of the exiles in the early 520s seems to have led to an ossification of the local church. Gregory the Great found much to lament when he gazed upon the poorly Christianized towns and landscapes of Corsica, but it was to Africa that he turned in the hope of a solution.173 The close ties that had been forged in the later fifth century still remained long after Vandal power itself had disappeared.

The Balearics - the islands of Mallorca, Minorca and Ibiza - offer little to compare. As has been discussed, the Vandals made raids on the islands as early as 425, but these were probably attacks in search of plunder, and by 449 the islands were back in imperial hands. Victor’s account includes the archipelago among the regions which were occupied by the Vandals in 455, but most modern scholars have assumed that the effective occupation only occurred in 460, during the attack on Majorian’s fleet at Cartagena.174 Most have been content to assume that the islands were occupied for purely strategic reasons. The Balearics offered the Vandals a military foothold in the western Mediterranean, which would have seemed valuable in the light of imperial and Visigothic activity along the coast of Spain. Thereafter, the islands probably remained safely Vandal, and sent three bishops to the Council of 484. It is not clear, however, when the occupation ended.

World History

World History