THE ACCESSION OF HENRY II BEGAN ONE OF THE MOST PREGNANT AND decisive reigns in English history. The new sovereign ruled an empire, and, as his subjects boasted, his warrant ran “from the Arctic Ocean to the Pyrenees.” England to him was but one—the most solid though perhaps the least attractive—of his provinces. But he gave to England that effectual element of external control which, as in the days of William of Orange, was indispensable to the growth of national unity. He was accepted by English and Norman as the ruler of both races and the whole country. The memories of Hastings were confounded in his person, and after the hideous anarchy of civil war and robber barons all due attention was paid to his commands. Thus, though a Frenchman, with foreign speech and foreign modes, he shaped our country in a fashion of which the outline remains to the present day.

After a hundred years of being the encampment of an invading army and the battleground of its quarrelsome officers and their descendants England became finally and for all time a coherent kingdom, based upon Christianity and upon that Latin civilisation which recalled the message of ancient Rome. Henry Plantagenet first brought England, Scotland, and Ireland into a certain common relationship; he re-established the system of royal government which his grandfather, Henry I, had prematurely erected. He relaid the foundations of a central power, based upon the exchequer and the judiciary, which was ultimately to supersede the feudal system of William the Conqueror. The King gathered up and cherished the Anglo-Saxon tradition of selfgovernment under royal command in shire and borough; he developed and made permanent “assizes” as they survive to-day. It is to him we owe the enduring fact that the English-speaking race all over the world is governed by the English Common Law rather than by the Roman. By his Constitutions of Clarendon he sought to fix the relationship of Church and State and to force the Church in its temporal character to submit itself to the life and law of the nation. In this endeavour he had, after a deadly struggle, to retreat, and it was left to Henry VIII, though centuries later, to avenge his predecessor by destroying the shrine of St. Thomas at Canterbury.

A vivid picture is painted of this gifted and, for a while, enviable man: square, thick-set, bull-necked, with powerful arms and coarse, rough hands; his legs bandy from endless riding; a large, round head and closely cropped red hair; a freckled face; a voice harsh and cracked. Intense love of the chase; other loves, which the Church deplored and Queen Eleanor resented; frugality in food and dress; days entirely concerned with public business; travel unceasing; moods various. It was said that he was always gentle and calm in times of urgent peril, but became bad-tempered and capricious when the pressure relaxed. “He was more tender to dead soldiers than to the living, and found far more sorrow in the loss of those who were slain than comfort in the love of those who remained.” He journeyed hotfoot around his many dominions, arriving unexpectedly in England when he was thought to be in the South of France. He carried with him in his tours of each province wains loaded with ponderous rolls which represented the office files of to-day. His Court and train gasped and panted behind him. Sometimes, when he had appointed an early start, he was sleeping till noon, with all the wagons and pack-horses awaiting him fully laden. Sometimes he would be off hours before the time he had fixed, leaving everyone to catch up as best they could. Everything was stirred and moulded by him in England, as also in his other much greater estates, which he patrolled with tireless attention.

But this twelfth-century monarch, with his lusts and sports, his hates and his schemes, was no materialist; he was the Lord’s Anointed, he commanded, with the Archbishop of Canterbury —“those two strong steers that drew the plough of England”—the whole allegiance of his subjects. The offices of religion, the fear of eternal damnation, the hope of even greater realms beyond the grave, accompanied him from hour to hour. At times he was smitten with remorse and engulfed in repentance. He drew all possible delights and satisfactions from this world and the next. He is portrayed to us in convulsions both of spiritual exaltation and abasement. This was no secluded monarch: the kings of those days were as accessible to all classes as a modern President of the United States. People broke in upon him at all hours with business, with tidings, with gossip, with visions, with complaints. Talk rang high in the King’s presence and to His Majesty’s face among the nobles and courtiers, and the jester, invaluable monitor, castigated all impartially with unstinted licence.

Few mortals have led so full a life as Henry II or have drunk so deeply of the cups of triumph and sorrow. In later life he fell out

With Eleanor. When she was over fifty and he but forty-two he is said to have fallen in love with “Fair Rosamond,” a damosel of high degree and transcendent beauty, and generations have enjoyed the romantic tragedy of Queen Eleanor penetrating the protecting maze at Woodstock by the clue of a silken thread and offering her hapless supplanter the hard choice between the dagger and the poisoned cup. Tiresome investigators have undermined this excellent tale, but it certainly should find its place in any history worthy of the name.

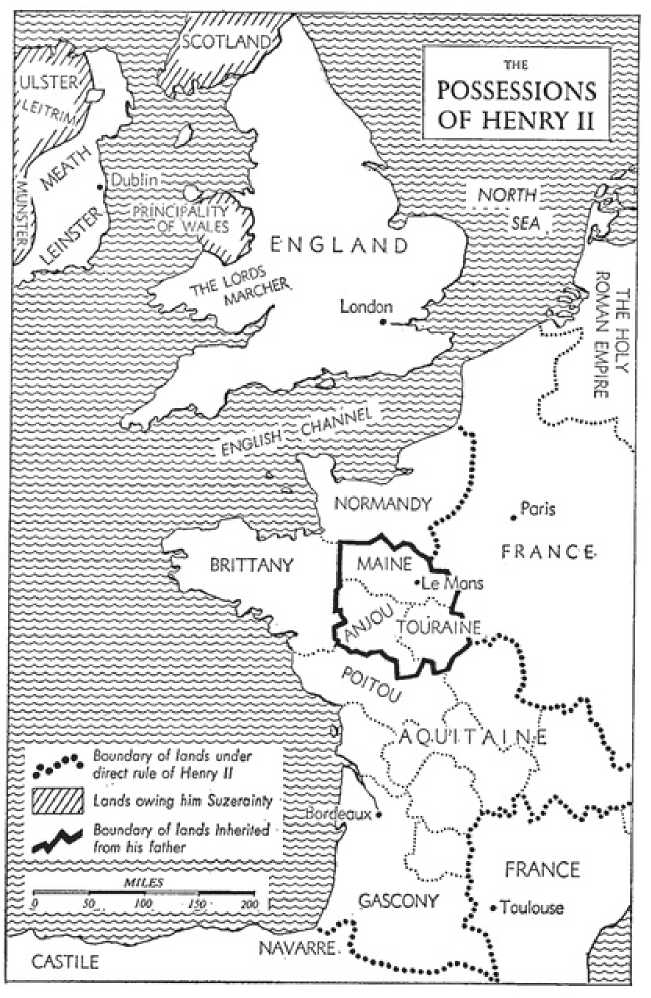

Such was the man who succeeded to the troubled and divided inheritance of Stephen. Already before his accession to the English throne Henry had fought the first of his many wars to defend his Continental inheritance. Ever since the emergence of the strong Norman power in North-West France, a hundred years before, the French monarchy had struggled ceaselessly against the encroachments of great dukedoms and countships upon the central Government. The Dukes of Normandy, of Aquitaine, and of Brittany, the Counts of Anjou, Toulouse, Flanders, and Boulogne, although in form and law vassals of the French Crown, together with a host of other feudal tenants-in-chief, aspired to independent sovereignty, and in the eclipse of the monarchy seemed at times near to achieving their ambition. The Battle of Hastings had made the greatest French subject, the Duke of Normandy, also King of England; but Henry II’s accession to the Island throne in 1154 threatened France with far graver dangers. Hitherto there had always been political relief in playing off over-mighty subjects one against another. The struggle between Anjou and Normandy in the eleventh century had rejoiced the French king, who saw two of his chief enemies at grips. But when in one hour Henry II was King of England, Duke of Normandy, Lord of Aquitaine, Brittany, Poitou, Anjou, Maine, and Guienne, ruler from the Somme to the Pyrenees of more than half France, all balance of power among the feudal lords was destroyed.

Louis VII found instead of a dozen principalities, divided and jealous, one single imperial Power, whose resources far surpassed his own. He was scarcely the man to face such a combination. He had already suffered the irreparable misfortune of Eleanor’s divorce, and of her joining forces and blood with his rival. By him she bore sons; by Louis only daughters. Still, some advantages remained to the French king. He managed to hold out for his lifetime against the Plantagenets; and after nearly four centuries of struggle and devastation the final victory in Europe rested with France. The Angevin Empire was indeed more impressive on the map than in reality. It was a motley, ill-knit collection of states, flung together by the chance of a single marriage, and lacked unity both of purpose and strength. The only tie between England and her Continental empire was the fact that Henry himself and some of his magnates held lands on either side of the Channel. There was no pretence of a single, central Government; no uniformity of administration or custom; no common interests or feelings of loyalty. Weak as Louis VII appeared in his struggle with the enterprising and active Henry, the tide of events flowed with the compact French monarchy, and even Louis left it more firmly established than he found it.

The main method of the French was simple. Henry had inherited vast estates; but with them also all their local and feudal discontents. Louis could no longer set the Count of Anjou against the Duke of Normandy, but he could still encourage both in Anjou and in Normandy those local feuds and petty wars which sapped the strength of the feudal potentates, in principle his vassals. Nor was the exploiting of family quarrels an unfruitful device. In the later years of his reign, the sons of Henry II, eager, turbulent, and proud, allowed themselves to be used by Louis VII and by his successor, the wily and gifted Philip Augustus, against their father.

How, we may ask, did all this affect the daily life of England and her history? A series of personal feudal struggles fought in distant lands, the quarrels of an alien ruling class, were little understood and less liked by the common folk. Yet these things long burdened their pilgrimage. For many generations their bravest and best were to fight and die by the marshes of the Loire or under the sun-baked hills of Southern France in pursuit of the dream of English dominion over French soil. For this two centuries later Englishmen triumphed at Crecy, Poitiers, and Agincourt, or starved in the terrible Limoges march of the Black Prince. For this they turned fertile France into a desert where even the most needed beasts died of thirst and hunger. Throughout the medieval history of England war with France is the interminable and often the dominant theme. It groped and scraped into every reach of English life, moulding and fretting the shape of English society and institutions.

No episode opens to us a wider window upon the politics of the twelfth century in England than the quarrel of Henry II with his great subject and former friend, Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury. We have to realise the gravity of this conflict. The military State in feudal Christendom bowed to the Church in things spiritual; it never accepted the idea of the transference of secular power to priestly authority. But the Church, enriched continually by the bequests of hardy barons, anxious in the death agony about their life beyond the grave, became the greatest landlord and capitalist in the community. Rome used its ghostly arts upon the superstitions of almost all the actors in the drama. The power of the State was held in constant challenge by this potent interest. Questions of doctrine might well have been resolved, but how was the government of the country to be carried on under two conflicting powers, each possessed of immense claims upon limited national resources? This conflict was not confined to England. It was the root question of the European world, as it then existed.

Under William the Conqueror schism had been avoided in England by tact and compromise. Under Lanfranc the Church worked with the Crown, and each power reinforced the other against the turbulent barons or the oppressed commonalty. But now a great personality stood at the summit of the religious hierarchy, Thomas Becket, who had been the King’s friend. He had been his Chancellor, or, as Ranke first remarked, “to use a somewhat equivalent expression, his most trusted Cabinet Minister.” He had in both home and foreign affairs loyally served his master. He had re-organised the imposition of scutage, a tax that allowed money to commute personal service in arms and thus eventually pierced the feudal system to its core. He had played his part in the acquisition of Brittany. The King felt sure that in Becket he had his own man—no mere servant, but a faithful comrade and colleague in the common endeavour. It was by the King’s direct influence and personal effort that Becket was elected Archbishop.

From that moment all his gifts and impulses ran in another channel. Something like the transformation which carried Henry V from a rollicking prince to the august hero-King overnight was now witnessed in Becket. His private life had always been both pious and correct. He had of course been immersed in political affairs; nor was it as a sombre figure behind the throne. But whereas hitherto as a courtier and a prince he had rivalled all in magnificence and pomp, taking his part in the vivid pageant of the times, he now sought by extreme austerities to gather around himself the fame and honour of a saint. Becket pursued the same methods and ambitions in the ecclesiastical as previously he had done in the political sphere; and in both he excelled. He now championed the Church against the Crown in every aspect of their innumerable interleaving functions. He clothed this aggressive process with those universal ideas of the Catholic Church and the Papal authority which far transcended the bounds of our Island, covering Europe and reaching out into the mysterious and the sublime. After a tour upon the Continent and a conclave with the religious dignitaries of France and Italy he returned to England imbued with the resolve to establish the independence of the Church hierarchy on the State as represented by the King. Thus he opened the conflict which the wise Lanfranc had throughout his life striven to avoid. At this time the mood in England was ripe for strife upon this issue.

In a loose and undefined way Saxon England had foreshadowed the theory to which the Elizabethan reformers long afterwards returned. Both thought of the monarch as appointed by God, not only to rule the State, but to protect and guide the Church. In the eleventh century however the Papacy had been reinvigorated under Hildebrand, who became Pope Gregory VII in 1073, and his successors. Rome now began to make claims which were hardly compatible with the traditional notions of the mixed sovereignty of the King in all matters temporal and spiritual. The Gregorian movement held that the government of the Church ought to be in the hands of the clergy, under the supervision of the Pope. According to this view, the King was a mere layman whose one religious function was obedience to the hierarchy. The Church was a body apart, with its own allegiance and its own laws. By the reign of Henry II the bishop was not only a spiritual officer; he was a great landowner, the secular equal of earls; he could put forces in the field; he could excommunicate his enemies, who might be the King’s friends. Who, then, was to appoint the bishop? And, when once appointed, to whom, if the Pope commanded one thing and the King another, did he owe his duty? If the King and his counsellors agreed upon a law contrary to the law of the Church, to which authority was obedience due? Thus there came about the great conflict between Empire and Papacy symbolised in the question of Investiture, of which the dispute between Henry II and Becket is the insular counterpart.

The struggle between Henry II and Becket is confused by the technical details over which it was fought. There was however good reason why the quarrel should have been engaged upon incidents of administration rather than upon the main principles which were at stake. The Crown resented the claim of the Church to interfere in the State; but in the Middle Ages no king dared to challenge the Church outright, or, much as he might hope to limit its influence, thought of a decisive breach. It was not till the sixteenth century that an English king in conflict with the Papacy dared to repudiate the authority of Rome and nakedly declare the State supreme, even in spiritual matters. In the twelfth century the only practicable course was compromise. But the Church at this time was in no mood for a bargain. In every country the secular power took up the challenge; but it was hard to meet, and in Central Europe at least the struggle ended only in the exhaustion of both Empire and Papacy.

The Church in England, like the baronage, had gained greatly in power since the days of William the Conqueror and his faithful Archbishop Lanfranc. Stephen in his straits had made sweeping concessions to the Church, whose political influence then reached its zenith. These concessions, Henry felt, compromised his royal rights. He schemed to regain what had been lost, and as the first step in 1162 appointed his trusted servant Becket to be Archbishop of Canterbury, believing he would thus secure the acquiescence of the Episcopacy. In fact he provided the Church with a leader of unequalled vigour and obstinacy. He ignored or missed the ominous signs of the change in Becket’s attitude, and proceeded to his second step, the publication in 1164 of the Constitutions of Clarendon. In these Henry claimed, not without considerable truth, to be re-stating the customs of the kingdom as they had been before the anarchy of Stephen’s reign. He sought to retrace thirty years and to annul the effects of Stephen’s surrender. But Becket resisted. He regarded Stephen’s yieldings as irrevocable gains by the Church. He refused to let them lapse. He declared that the Constitutions of Clarendon did not represent the relations between Church and Crown. When, in October 1164, he was summoned to appear before the Great Council and explain his conduct he haughtily denied the King’s authority and placed himself under the protection of the Pope and God.

Thus he ruptured that unity which had hitherto been deemed vital in the English realm, and in fact declared war with ghostly weapons upon the King. Stiff in defiance, Becket took refuge on the Continent, where the same conflict was already distracting both Germany and Italy. The whole thought of the ruling classes in England was shaken by this grievous dispute. It endured for six years, during which the Archbishop of Canterbury remained in his French exile. Only in 1170 was an apparent reconciliation brought about between him and the King at Freteval, in Touraine. Each side appeared to waive its claims in principle. The King did not mention his rights and customs. The Archbishop was not called upon to give an oath. He was promised a safe return and full possession of his see. King and Primate met for the last time in the summer of 1170 at Chaumont. “My lord,” said Thomas at the end, “my heart tells me that I part from you as one whom you shall see no more in this life.” “Do you hold me as a traitor?” asked the King. “That be far from thee, my lord,” replied the Archbishop; but he returned to Canterbury resolved to seek from the Pope unlimited powers of excommunication wherewith to discipline his ecclesiastical forces. “The more potent and fierce the prince is,” he wrote, “the stronger stick and harder chain is needed to bind him and keep him in order.” “I go to England,” he said, “whether to peace or to destruction I know not; but God has decreed what fate awaits me.”

Meanwhile, in Becket’s absence, Henry had resolved to secure the peaceful accession of his son, the young Henry, by having him crowned in his own lifetime. The ceremony had been performed by the Archbishop of York, assisted by a number of other clerics. This action was bitterly resented by Becket as an infringement of a cherished right of his see. After the Freteval agreement Henry supposed that bygones were to be bygones. But Becket had other views.

His welcome home after the years of exile was astonishing. At Canterbury the monks received him as an angel of God. “I am come to die among you,” he said in his sermon, and again, “In this church there are martyrs, and God will soon increase their number.” He made a triumphal progress through London, scattering alms to the beseeching and exalted people. Then hotfoot he proceeded to renew his excommunication of the clergy who had taken part in the crowning of young Henry. These unfortunate priests and prelates traveled in a bunch to the King, who was in Normandy. They told a tale not only of an ecclesiastical challenge, but of actual revolt and usurpation. They said that the Archbishop was ready “to tear the crown from the young King’s head.”

Henry Plantagenet, first of all his line, with all the fire of his nature, received these tidings when surrounded by his knights and nobles. He was transported with passion. “What a pack of fools and cowards,” he cried, “I have nourished in my house, that not one of them will avenge me of this turbulent priest!” Another version says “of this upstart clerk.” A council was immediately summoned to devise measures for reasserting the royal authority. In the main they shared the King’s anger. Second thoughts prevailed. With all the stresses that existed in that fierce and ardent society, it was not possible that the realm could support a fearful conflict between the two sides of life

Represented by Church and State.

But meanwhile another train of action was in process. Four knight had heard the King’s bitter words spoken in the full circle. They travelled fast to the coast. They crossed the Channel. They called for horses and rode to Canterbury. There on December 29, 1170, they found the Archbishop in the cathedral. The scene and the tragedy are famous. He confronted them with Cross and mitre, fearless and resolute in warlike action, a master of the histrionic arts. After haggard parleys they fell upon him, cut him down with their swords, and left him bleeding like Julius Casar, with a score of wounds to cry for vengeance.

This tragedy was fatal to the King. The murder of one of the foremost of God’s servants, like the breaking of a feudal oath, struck at the heart of the age. All England was filled with terror. They acclaimed the dead Archbishop as a martyr; and immediately it appeared that his relics healed incurable diseases, and robes that he had worn by their mere touch relieved minor ailments. Here indeed was a crime, vast and inexpiable. When Henry heard the appalling news he was prostrated with grief and fear. All the elaborate process of law which he had sought to set on foot against this rival power was brushed aside by a brutal, bloody act; and though he had never dreamed that such a deed would be done there were his own hot words, spoken before so many witnesses, to fasten on him, for that age at least, the guilt of murder, and, still worse, sacrilege.

The immediately following years were spent in trying to recover what he had lost by a great parade of atonement for his guilt. He made pilgrimages to the shrine of the murdered Archbishop. He subjected himself to public penances. On several anniversaries, stripped to the waist and kneeling humbly, he submitted to be scourged by the triumphant monks. We may however suppose that the corporal chastisement, which apparently from the contemporary pictures was administered with birch rods, was mainly symbolic. Under this display of contrition and submission the King laboured perseveringly to regain the rights of State. By the Compromise of Avranches in 1172 he made his peace with the Papacy on comparatively easy terms. To many deep-delving historians it seems that in fact, though not in form, he had by the end of his life re-established the main principles of the Constitutions of Clarendon, which are after all in harmony with what the English nation or any virile and rational race would mean to have as their law. Certainly the Papacy supported him in his troubles with his sons. The knights, it is affirmed, regained their salvation in the holy wars. But Becket’s sombre sacrifice had not been in vain. UntH the Reformation the Church retained the system of ecclesiastical courts independent of the royal authority, and the right of appeal to Rome, two of the major points upon which Becket had defied the King.

It is a proof of the quality of the age that these fierce contentions, shaking the souls of men, should have been so rigourously and yet so evenly fought out. In modern conflicts and revolutions in some great states bishops and archbishops have been sent by droves to concentration camps, or pistolled in the nape of the neck in the well-warmed, brilliantly lighted corridor of a prison. What claim have we to vaunt a superior civilisation to Henry Il’s times? We are sunk in a barbarism all the deeper because it is tolerated by moral lethargy and covered with a veneer of scientific conveniences.1

Eighteen years of life lay before the King after Becket’s death. In a sense, they were years of glory. All Europe marvelled at the extent of Henry’s domains, to which in 1171 he had added the Lordship of Ireland. Through the marriages of his daughters he was linked with the Norman King of Sicily, the King of Castile, and Henry the Lion of Saxony, who was a most powerful prince in Germany. Diplomatic agents spread his influence in the Lombard cities of northern Italy. Both Emperor and Pope invited him in the name of Christ and all Europe to lead a new Crusade and to be King of Jerusalem. Indeed, after the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick Barbarossa, Henry stood next in Christendom. It was suspected by his contemporaries that his aim was to win for himself a kingdom in Italy and even to wear the imperial crown.

Yet Henry knew well that his splendour was personal in origin, tenuous and transient in quality; and he had also deep clouding family sorrows. During these years he was confronted with no less than four rebellions by his sons. For the three eldest he had provided glittering titles; Henry held Normandy, Maine and Anjou; Richard was given Aquitaine, and to Geoffrey went Brittany. These boys were typical sprigs of the Angevin stock. They wanted power as well as titles, and they bore their father no respect. Urged on by their mother, Queen Eleanor, who now lived in Poitiers apart from her husband, between 1173 and 1186 they rose in revolt in various combinations. On each occasion they could count on the active support of the watchful King of France. Henry treated his ungrateful children with generosity, but he had no illusions. The royal chamber at Westminster at this time was adorned with paintings done at the King’s command. One represented four eaglets preying upon the parent bird, the fourth one poised at the parent’s neck, ready to pick out the eyes. “The four eaglets,” the King is reported to have said, “are my four sons who cease not to persecute me even unto death. The youngest of them, whom I now embrace with so much affection will sometime in the end insult me more grievously and more dangerously than any of the others.”

So it was to be. John, whom he had striven to provide with an inheritance equal to that of his brothers, joined the final plot against him. In 1188 Richard, his eldest surviving son, after the death of young Henry, was making war upon him in conjunction with King Philip of France. Already desperately ill, Henry was defeated at Le Mans and recoiled to Normandy. When he saw in the list of conspirators against him the name of his son John, upon whom his affection had strangely rested, he abandoned the struggle with life. “Let things go as they will,” he gasped. “Shame, shame on a conquered King.” So saying, this hard, violent, brilliant and lonely man expired at Chinon on July 6, 1189. The pious were taught to regard this melancholy end as the further chastisement of God upon the murderer of Thomas Becket. Such is the bitter taste of worldly power. Such are the correctives of glory.

World History

World History