Byzantine literature is remembered for two opposing tendencies. On the one hand, there was the literature of hagiography (hay-jee-AHG-ruh-fee), official biographies of the Eastern Orthodox saints. These were a mixture of truth and legend, designed to provide readers both with entertainment and a moral lesson. Hagiography exaggerated the best qualities of the subject. On the other hand, Byzantium's gossipy historians (who also sometimes presented tall tales as fact) often tried to make people seem worse than they were, not better.

Such was the case with Procopius (pruh-KOH-pee-us), a historian of the 500s. Though he wrote a highly acclaimed account of Justinian's wars of conquest, Procopius secretly held deep grudges against the emperor, the empress Theodora, and others. Therefore he wrote a work in which he told what he really thought. Procopius's Secret History was not published until many centuries after his death, and no wonder: had it been discovered, he would undoubtedly have been executed. Its chapters have titles such as "Proving That Justinian and Theodora Were Actually Fiends [i. e., demons] in Human Form."

The empress had been a prostitute in her younger days, and Procopius spared no detail regarding her shady past, his account at times verging on pornography. Other historians, by contrast, offer positive accounts of Theodora, and indeed it is hard to trust Procopius. He was a member of the Green faction, whereas Theodora supported the Blues, and this may explain some of his ill will.

Cism. Instead of the Cyrillic alphabet, they adopted the Roman alphabet, used in virtually all Western nations (including the United States) today. Just to the north of Serbia was Croatia, whose people became a part of Charlemagne's empire, as did neighboring Slovenia. To the northeast was Hungary, one of the few nations in Eastern Europe that is neither Slavic nor Orthodox: its dominant Magyar population became Catholic after their defeat by Otto the Great in 955.

North of Hungary was Moravia, converted to Orthodoxy by Cyril and

Methodius. Later it would become Catholic after its conquest by Bohemia, itself converted during the 800s by German missionaries. Bohemia and Moravia, today part of the Czech Republic, would enjoy periods of great influence during the Middle Ages. Moravia briefly conquered a large area, including Slovakia to the east, in the late 800s; and during the 1200s Bohemia emerged as a great power.

Finally, there was the northernmost and most influential of the Slavic Catholic nations: Poland, whose king adopted Christianity in

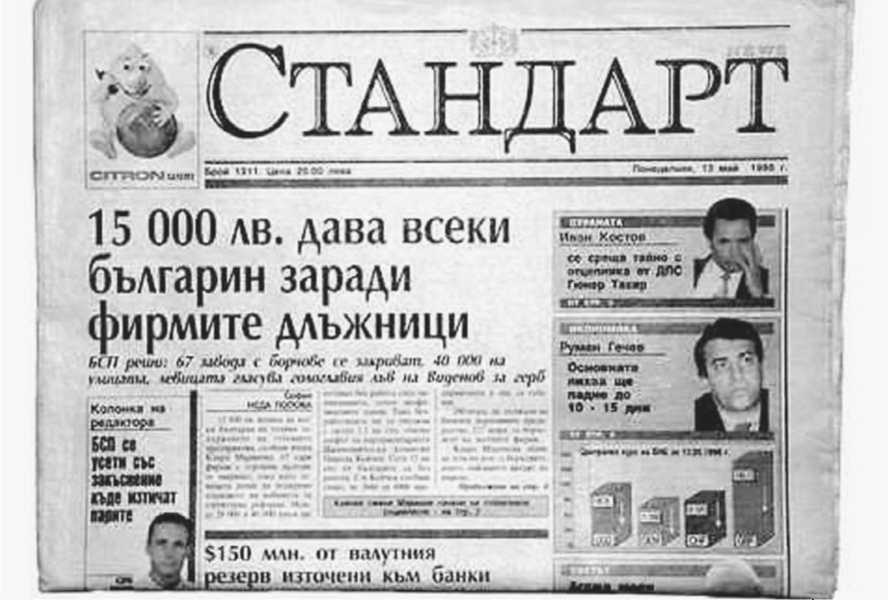

This Bulgarian newspaper shows an example of the Cyrillic alphabet, which was developed by St. Cyril (c. 827-869). Reproduced by permission of EPD Photos.

966. Thus a large part of Slavic Eastern Europe was Catholic, yet to the east was a single Orthodox nation that became larger than all of Eastern Europe combined: Russia.

World History

World History