The composition of the nation’s currency was a major political issue of the late 19th century. bimetallism (currency based on gold and silver) was federal monetary policy until 1873. The government coined silver at the ratio of 16-to-one; the silver dollar contained 16 times more silver than there was gold in a gold dollar. During the Civil War, however, the government printed $450 million in paper currency called “greenbacks,” a fiat currency that was not backed by any specie. Greenbacks could not be redeemed in gold, and as their value declined they drove gold and silver out of circulation. In addition, national banks were allowed by the National Banking Act of 1863 to issue $300 million in notes redeemable in greenbacks, thus making these notes, in effect, equal to greenbacks.

The suspension of specie payments did not sit well with bankers and other creditors. Following the war, they called for the retirement of greenbacks and a resumption of specie payments. Such a policy would lead to deflation by keeping the value of the dollar—and thus interest rates and the value of debts owed to creditors—high. Debtor groups, especially in the cash-strapped South and West, pressured the government to further inflate the currency supply by placing more greenbacks into circulation. They believed the ensuing inflation (rise in prices and lowered interest rates) would make it easier to pay off their debts.

A major issue tied to the currency question was the constitutionality of the Legal Tender Act of 1862, which authorized the Treasury to issue the greenbacks. At the time it was argued that this measure was necessary to finance the Union war effort. Following the war, proponents of sound, or hard, money—a currency based on the gold standard—called for the resumption of specie payments. In 1866 Congress passed the Contraction Act, which initiated a policy of gradual reduction of the greenbacks in circulation. Debtors immediately attacked the law because it made their debts harder to pay off. Others blamed it for the worsening economic conditions of 1867. The constitutionality of the Legal Tender Act was finally taken up by the Supreme Court in a set of cases known collectively as the LEGAL-TENDER CASES (1870-71). In Hepburn v. Griswold (1870), the Court decided that the greenbacks issued during the Civil War were not legal tender for debts incurred prior to the act’s passage in 1862, but the Court quickly reversed the Hepburn decision in Knox v. Lee (1871), holding that greenbacks were valid legal tender for pre-as well as post-1862 debts. Although the Knox decision dealt hard-money advocates a serious setback, they would not allow themselves to be defeated.

In 1873 Congress enacted the Coinage Act, which effectively demonetized silver, making the gold dollar the monetary standard for the nation. The 16-to-one ratio had undervalued silver ever since the 1849 California gold rush lowered the price of gold. As a result, silver-mine operators sold their product commercially rather than to the government at a loss, virtually taking the silver dollar out of circulation. Since silver was being used for purposes other than coinage and the silver dollar had almost disappeared from circulation anyway, experts urged Congress to demonetize it. Two years after Congress demonetized silver, it enacted the Specie Resumption Act, authorizing the Treasury to resume, by January 1, 1879, the redemption of greenbacks in gold. As of that date the United States was back on the gold standard.

Reacting to the Specie Resumption Act, the advocates of “soft money” (greenbacks) conferred in Cleveland and Cincinnati, Ohio; held a convention in May 1876 in Indianapolis, Indiana; and organized a National Independent (Greenback) Party. These Greenbackers—farmers, labor reformers, and businessmen—called for the repeal of the Specie Resumption Act and nominated the 85-year-old philanthropist Peter Cooper for president. Cooper received only 80,000 votes, but the Greenback-Labor Party was far more successful in the congressional elections of 1878, polling more than 1 million votes. In 1880 the party’s presidential candidate General James B. Weaver of Iowa polled 300,000 votes. However, by the mid-1880s the Greenback Party began to disintegrate. As a consequence, Greenback-ers joined with another group of currency inflationists, the advocates of Free Silver, to create a powerful political movement in late-19th-century America.

Shortly after Congress enacted the Coinage Act, new mines in Nevada and other parts of the Far West increased the production of silver and thus lowered its value. If the government had kept silver in circulation, the subsequent deflationary price spiral might not have occurred. Instead, the nation entered a period of economic depression, with

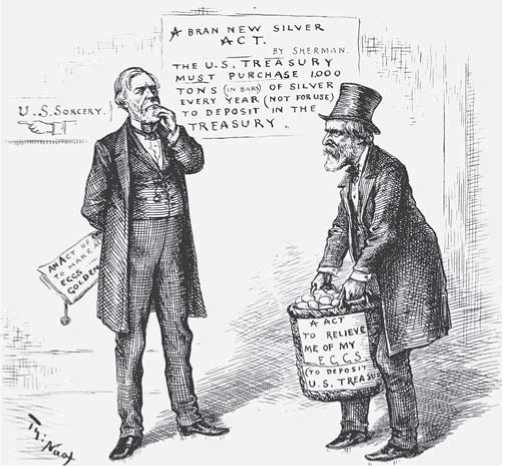

This cartoon depicts Senator John Sherman delivering silver "eggs" to Secretary of the Treasury John G. Carlisle, who will turn them into gold. (New York Public Library)

American farmers struck the hardest as agricultural prices declined. Because of falling farm prices and the desire of western silver producers to see demand for their product increase, debtor farmers and western silver-mining interests began to call for the remonetization of silver at the old ratio of 16-to-one. The removal of the silver dollar from circulation and the redemption of greenbacks were viewed as part of a larger scheme orchestrated by bankers and other financiers (chief supporters of the hard-money philosophy) to control the money supply and prevent price recovery.

In 1878 silverites won a partial victory when Congress passed the Bland-Allison Act authorizing a limited, but not free, coinage of silver. The law required the government to buy no less than $2 million or more than $4 million worth of silver monthly and then to mint it into silver dollars. The Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890 increased the amount of silver coinage in circulation by obligating the government to purchase 4.5 million ounces of silver monthly. The silver was to be paid for in Treasury notes of full legal-tender value that could be redeemed in “coin” at the discretion of the government. Treasury officials interpreted this provision as meaning redemption in gold, placing a great strain on the nation’s gold reserve.

When the economic depression following the panic of 1893 set in, hard-money advocates blamed the downturn on the Sherman Silver Purchase Act. President Grover Cleveland, a hard-money advocate, called for and secured its repeal in 1893 with the support of several congressional Republicans and Democrats (mostly from the

Northeast), thereby alienating the southern and western factions of both parties.

The calls for the free coinage of silver became more strident following the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act and set the stage for one of the most bitter and emotionally charged political contests in American history. Between 1894 and 1900 pro-silver literature flooded the nation. From William H. Harvey’s Coin’s Financial School (1894) and Ignatius Donnelly’s The American People’s Money (1895) to L. Frank Baum’s classic The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), authors argued the virtues and merits of silver. In 1896 both the Democratic Party and the People’s Party (Populists) adopted Free Silver as their main campaign theme and nominated William Jennings Bryan for president. However, Bryan was defeated that year by the Republican presidential candidate William McKinley, who ran on a platform supporting the gold standard. Bryan’s defeat was a major setback for the Free Silver movement from which it never recovered. In 1900 Congress passed the Gold Standard Act, which declared gold the nation’s monetary standard of value and ended the silver controversy.

See also Crime of ’73; earmers’ alliances; Omaha plateorm; political parties, third; Simpson, Jerry.

Further reading: Walter T. K. Nugent, Money and American Society, 1865-1880 (New York: Free Press, 1968); Robert P Sharkey, Money, Class, and Party: An Economic Study of the Civil War and Reconstruction (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1959); Irwin Unger, The Greenback Era: A Social and Political History of American Finance, 1865-1879 (Princeton, N. J.: Princeton University Press, 1964).

—Phillip Papas

Currier and Ives See illustration, photography, and the graphic arts.

Curtis, George William See civil service reeorm.

World History

World History