I say, beware of all enterprises that require new clothes, and not rather a wearer of new clothes.

—Henry David Thoreau

In this book, I consider the dress, clothing, and adornment of peoples living in seventeenth - and eighteenth-century North America through the lens of historical archaeology, aided by ethnographic, historical, and visual sources. The archaeological record provides us with a narrow view of clothing and adornment: a button from a cloak or a buckle from a shoe is usually all that remains from an item or garment. We can learn more of the entire item or garment through other sources: paintings, account books, and ethnographic collections. Each of these sources provides a slightly different (and often biased) view of colonial dress. But at their intersection, we have the potential to understand how the tiny button recovered from an eighteenth-century privy was attached to clothing, how the person dressed in that fashion moved through a somewhat unstable colonial world, and, more importantly, how dress in colonial America mattered.

One need only reference the crimson “A” worn by Hester Prynne in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter to imagine the impact of clothing and adornment in the colonies. During the colonial period, clothing was important not only for Puritans living in New England but also for Native Americans, Europeans, Africans, and peoples of multiethnic ancestry occupying settlements and towns throughout North America. Dress was a social medium. The color, fabric, and fit of clothing in combination with adornments, posture, and manners conveyed information about status, occupation, religious beliefs, and even sexual preferences of the clothed and

Adorned person (see Anderson 2005; Entwistle 2000; Richardson 2004). Clothing and adornment is therefore important not only for its utility but also for its expressive properties and the ability of the wearer to manipulate properties embodied through dress (Shannon 1996:17).

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, European production of clothing, cloth, and adornment was blossoming, tied to a growing global economy (Baumgarten 2002). New fabrics, buttons, beads, shoes, and shirts were just some of the items available to peoples living in North America. Clothing, which was still largely constructed by hand, was made both within and outside North America. Quite literally, a new world of clothing (and by extension fashion) was available to communities outside Europe (Breen 1993). During these centuries, English, Spanish, Dutch, French, and Russian colonies in North America were populated by Europeans, Africans, Native Americans, and individuals of multiethnic ancestry. Each of these groups had different dressing traditions. Because of the complex makeup of peoples inhabiting North America and the interest of colonial officials in controlling this population, ideas, rules, and restrictions about the ways that certain people were to dress were abundant. Not everyone could take

1.1. The Bermuda Group (Dean Berkeley and His Entourage), painting by John Smibert, 1729. Courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery.

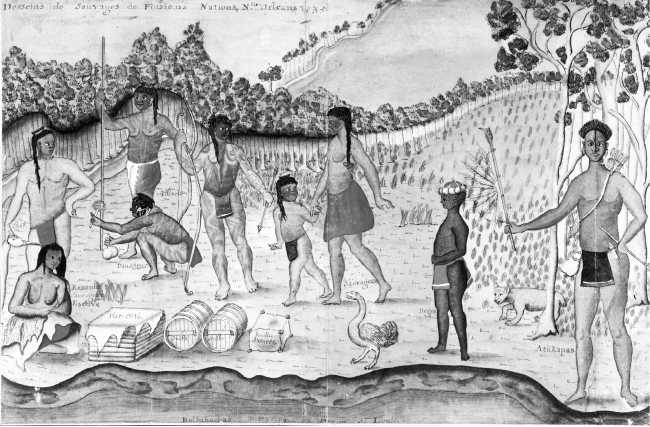

1.2. Desseins de Sauvages de Plusieurs Nations, watercolor by Alexandre de Batz, ca. 1734. Courtesy of President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 41-72-10/20.

Advantage of new fashions or dress in the ways they wished. Despite such limitations (or attempted limitations), colonial peoples dressed in ways that strained against the seams of colonial rule.

The image that clothing and adornment in colonial America conjures in the minds of many is the one found at historical reenactment sites such as colonial Williamsburg: men wearing frock coats and knee breeches, their heads covered by powdered wigs and tricorn hats (Figure 1.1). These images of colonial elites are tempered by other depictions of the peoples and fashions that populated colonial North America. A 1734 watercolor by Alexandre de Batz that illustrates different Native and African peoples living in French colonial Louisiana was drawn just five years after John Smibert’s painting of Dean Berkeley and his entourage (Figure 1.2). The style and medium of the two images are quite different, but generally speaking their subject is the same: colonial peoples. The individuals depicted in these images were from different ethnic and racial backgrounds, occupied different physical spaces in the colonial world, and wore different styles of clothing and adornment. These images illustrate that there was no single fashion or preferred style of dressing for the many peoples who lived in North

America; their dress was as diverse as the physical and social spaces they occupied. What these images fail to capture is the ingenuity and creativity of colonial dress—how different groups of people living together in communities throughout North America consciously clothed and adorned their bodies in specific ways to create a sense of self and present that self in their worlds. Jean Comaroff (1996:19) notes that dress was “a privileged means for constructing new forms of value, personhood, and history on the colonial frontier.” Although her writing focuses on colonial South Africa, Comaroff’s words have relevance for colonial North America. While no one fashion typified colonial life, what was integral to the American colonial experience was that people created specific fashions of clothing and adornment appropriate to their context and their daily experiences (see Shannon 1996; St. George 2000).

In colonial North America, individuals from many ethnic groups transformed clothing traditions through processes of cultural exchange. The strategies they used suggest a pattern of dressing in colonial North America that is best characterized as a patchwork, a mixture of local and imported, Native and non-Native, handmade and manufactured. The strategy of combining locally made and imported goods created a new language of appearance that individuals used to communicate self and identity in an often-contentious colonial world (Comaroff 1996; Shannon 1996:19). In this book, I explore the active manipulation of the material culture of clothing and adornment by people in English, Dutch, French, and Spanish colonies. I examine how peoples in these different contexts combined objects of clothing and adornment in unique ways to dress themselves in distinct fashions.

While historical and visual accounts of the colonial past are informative about the ways various peoples dressed (and these sources are used almost exclusively in period reenactments), they provide only one perspective. This perspective is inherently biased toward elite European men and offers little surviving information about the other peoples who occupied colonial landscapes. When we look to historical sources to visually recreate past life, we must take care not to do so at the expense of the women, children, Africans, Native Americans, and servants who lived in the margins of historical narratives. That historical archaeology is best suited to provide detailed information about the daily practices of colonial peoples that takes into account ethnicity, gender, or race is a well-established tenet of the discipline (for just a few examples, see Beaudry 1998; Deagan 1988; Hall 1992, 2000; Orser 2007).

When we focus our gaze on American history, we seek to visualize the characters in that past. While paintings, illustrations, woodcuts, and historical texts provide some description primarily about the dress of elite male individuals, we are left to imagine the dress of others, especially those overlooked in historical documents. This is where historical archaeology can broaden and (at times) challenge popular and academic representations of the clothing and adornment of colonial peoples.

Archaeologists study the residue of people’s lives that has been left behind: the objects lost or discarded in daily activities or purposefully placed with a loved one at the time of burial. As an historical archaeologist, the category of material culture that seems to occupy my time and interest is small finds: those buttons, buckles, jewelry, fabric, and beads found on archaeological sites that are the remnants of pieces of clothing and adornment. The fact that we find these objects in a variety of contexts tells us much about who wore what and how they wore it. During the colonial period, numerous goods manufactured in Europe—items such as textiles, buttons, and glass beads—were shipped to North America in bulk lots. The movement of these goods to colonial communities along with sumptuary laws (official ideals of how colonial peoples were to dress) were meant to set the fashion and tastes for colonial populations. Imperial leaders had a certain vision of dress for their populations and went to great lengths to make sure that those visions were realized (Breen 1993).

Once ships arrived in the colonies, goods were sent to merchants and warehouses from which colonial people could outfit their wardrobes. Because of this global market, some of the same items used in practices of dressing are found at very different types of sites in the French, English, Dutch and Spanish colonies of North America. For example, in the eighteenth century, metal sleeve buttons manufactured in England were shipped across the Atlantic to adorn the clothes of Wampanoag, African, and English peoples living in New England and the mid-Atlantic. As a result, the same style of sleeve buttons found in the basement of the first college building in North America was also found buried with an African man in New York. In this case and many others, while the same item of clothing and adornment may have been found in different contexts, it was mobilized in distinct ways by colonial peoples to create different fashions in the colonies that led to multifaceted and multilayered visions of dress in the American experience.

This book in not intended as a sourcebook for identifying objects of clothing and adornment in the archaeological record. Several excellent sourcebooks of this kind have already been published (e. g., Deagan 2002; Noel Hume 1969; White 2005). My intent in this book is to problematize and unpack notions of colonial clothing and adornment by examining a variety of classes of data that are available to the historical archaeologist: archaeological, ethnographic, historical, and visual.

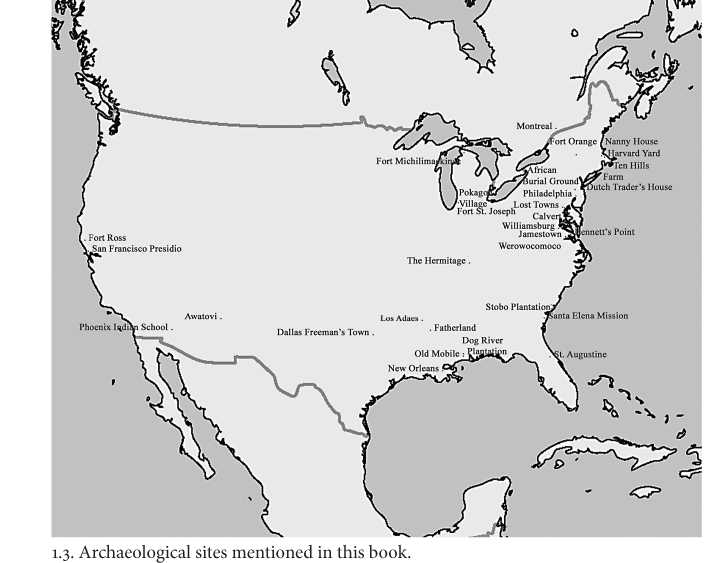

The examples of clothing and adornment discussed in this book focus on how people manipulated and combined objects that were manufactured both locally and abroad. I draw from the sources I just mentioned— archaeological, ethnographic, historical, and visual—to illustrate some of the unique combinations of clothing and adornment found throughout colonial North America. I rely heavily on collections of colonial material housed within the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University. As the oldest museum of archaeology and ethnology in the western hemisphere, the museum is steward to very early ethnographic collections from North America as well as collections from numerous archaeological investigations. In addition to these museum collections, I compare similar material culture from other colonial contexts, relying on anthropological and archaeological scholarship (Figure 1.3).

One of the great advantages of interdisciplinary research is that scholars can discover disjunctures between sources and silences that illuminate points of contention and anxiety about colonial policies and practices (Hall 1992, 2004; Loren and Baram 2007; Stahl 1993). For example, when we direct our attention to material culture alone, we must be aware of biases in categorization and interpretation. Emphasizing one category in iso-lation—for example, the glass bead over the beaded garment—may limit what we can say about how identity was constituted using material culture. What can we know of the lives and struggles of people from an investigation of artifact assemblages that at first glance seem to contain unlikely and dissonant combinations of different categories of material culture? The answer lies in comparison—not only comparing the artifacts present in the assemblage but also comparing the artifacts we have with those that are not present. We must also look at the ways that the remnants of daily practices are or are not represented in historical, visual, and ethnographic material.

Not every example of clothing and adornment found in colonial contexts is examined in this book. Rather, I spotlight a few examples of specific kinds of clothing and adornment that have been recovered from multiple colonial contexts, lingering on those that best illustrate how a simple button, for example, can take on a multitude of meanings when worn by different colonial peoples. The purpose of my approach is to stimulate ideas about the ways that small things that have been forgotten about clothing and adornment provide an entry point into the thought worlds and practices of colonial men, women, and children of varying ethnic backgrounds. These clothing styles comprise the fabric of the American experience.

Interpreting the Clothed and Adorned Colonial Body

Theoretical approaches to dress, clothing, and fashion have long been discussed within the fields of history, art history, and visual studies. These approaches garnered attention within anthropology in the 1950s and 1960s, becoming popular in the 1990s through the work of Joanne B. Eicher and

Mary Ellen Roach-Higgins (Barnes and Eicher 1993; Eicher 1999; Eicher and Roach-Higgins 1992; Roach and Eicher 1965, 1973). Such works amplify the notion that clothing and adornment are a means of communication: a visual statement about status, prestige, gender, society, politics, and religion (see Anderson 2005; Entwistle 2000; Richardson 2004). Clothing faces both inward and outward, a notion Terence Turner (1993 [1980]) evoked when he coined the term “social skin.” Culture, the individual, and clothing are inextricably linked, as there is often no more powerful, individualized statement of and about society than the way that someone dresses. Just a single button can provide insight into social identities and networks of trade, power, and production. Cross-cultural analysis reveals that in all societies bodies are “dressed” in some way and that everywhere clothing and adornment play “symbolic, communicative and aesthetic roles” (Wilson 1995:3). For these reasons, clothing has been a powerful topic for anthropologists, archaeologists, and scholars of material culture studying a variety of cultures and time periods (see, for example, Anderson 2005; Eicher and Roach-Higgins 1992; Eicher 1995; Goodwin 1999; Greenblatt 1984; Neill 2000; Richardson and Kroeber 1952; Schneider 2006; Shannon 1996; Stoler 2001; Weiner 1985; Weiner and Schneider 1989).

Historical archaeologists have long been mindful of the need to identify and categorize artifacts of clothing and adornment. There are deep traditions of interpreting objects of clothing and adornment at colonial sites such as Williamsburg, Fort Ross, Old Mobile, and the Spanish mission settlements of Florida (Baumgarten 2002; Deagan 2002; Lightfoot 1995; Quimby 1966; Waselkov 1992). Classic volumes within the discipline, such as Ivor Noel Hume’s A Guide to the Artifacts of Colonial America (1969), are devoted to processes for identifying, classifying, and dating historical artifacts that are crucial to interpretive strategies (see also Emery and Fiske 1985). Scholars have also examined the manufacture, consumption patterns, and trade patterns related to the material culture of clothing and adornment (see, for example, Claassen 1994; Hamell 1983).

This material culture is commonly analyzed through the lenses of ethnicity, gender, and sexuality, with increasing emphasis being placed on the intersection of issues of materiality and embodiment (e. g., Comaroff 1996; Eicher 1999; Eicher and Roach-Higgins 1992:12; Greenblatt 1984; Voss 2008b; Weiner 1985; Weiner and Schneider 1989; see also Schneider 2006). Hansen (2003) outlines the growing interest in clothing within anthropology over the past two decades, pointing to book series such as Berg

Publishers’ Dress, Body, and Culture series as examples of this trend. Yet in the absence of information related to gender, age, or ethnicity, a single article of clothing is usually interpreted along rather conservative lines, influenced by existing stereotypes or knowledge claims.

Dress is more than a surface phenomenon. Clothing and adornment do not just live on the exterior of one’s body. How a person dresses, the sense of self that a person wishes to embody, is part of his or her bodily experience. Social archaeology—an exploration of the intersection of people and material culture—is necessary if we are to understand an individual’s bodily experience with and in the colonial world (see Goodwin 1999; Gosden and Knowles 2001; Joyce 1998, 2005; Loren 2001a, 2001b, 2007a; Meskell 2002, 2004; Nassaney 2004). Broadly stated, social archaeology “conceptualized as an archaeology of social being can be located at the intersections of temporality, spatiality and materiality” (Pruecel and Meskell 2004:3). Within social archaeology, the body as a social and physical being has become more prominent. At the intersection of time, space, and the material, it is through the body that a person experiences the world, forms a sense of self and identity, and mediates social exchanges and social constructions of race, gender, power, and age (Butler 1990; Merleau-Ponty 1989; for further discussion of these concepts see Calefato 2004; Colchester 2003; DeMarrais et al. 2004; Entwistle and Wilson 2001; Gosden and Knowles 2001; Joyce 1998, 2005; Meskell 2004; Miller 2005; Thomas 1991; Voss 2008a).

In this book I investigate some of the ways that colonial peoples chose to express their bodies and identities through clothing and adornment. The body is at the core of this analysis. More than simply a mannequin for clothes, people’s bodies were at the center of most colonial discussions of self and other. European racialization of Native and African bodies was in full swing by the mid-seventeenth century; most Europeans, regardless of their social status, claimed moral, bodily, and cultural superiority over these groups (Chaplin 2003:9, 14; Orser 2007). The body was the area where sexual, racial, and cultural differences were played out, making it possible for various peoples to visually understand and portray notions of comportment, nature, culture, intention, religious preference, and economic and social status (Deagan 2002; Loren 2001b, 2007a, 2007b).

Dress as a material expression of self was subject to change and innovation in relation to specific colonial contexts. The notion of “one costume, one culture” must be discarded if we seek to understand the diversity of clothing and identities in North American history. In this book, I ground

My discussions in current theoretical perspectives on embodiment and materiality, which makes possible a discussion of how objects of clothing and adornment were an integral part of people’s daily lives and how colonial identities were constituted through the active manipulation of material culture.

The Lives of Clothing and Objects of Adornment

This book explores the clothed and adorned body in colonial North America through the lens of historical archaeology. To bring out the ways that people actively manipulated clothing and adornment, we must interrogate the context in which objects of clothing and adornment were entangled with the lives of the people who created and wore them. As numerous examples from the archaeological, ethnographic, documentary, and visual records suggest, a tension often existed between the meaning an object once held for its producer and the ways that object was used, manipulated, and appreciated later in its life by another individual. While there is value in understanding the nature of the political or economic functions of objects at the time of manufacture, when we emphasize this aspect of an object’s life over others we often strip away the connections between the object and its impact and import in the lives of colonial peoples. In ascribing the notion of “life” to an object, I wish to highlight the lives objects lead outside the context of the lifespan of an individual owner and how objects constrain and influence the lives of the people with whom they come in contact (Hill 2007; Miller 2005).

The eighteenth-century embroidered leather bag in Figure 1.4 provides an example of the changes in the life of an object as it moves from manufacturer to owner. The bag was most likely constructed by an Iroquois individual, and the porcupine and moose-hair embroidery that decorate the bag are similar to the decorations on other bags from the same period (Phillips 1998). What distinguishes this bag from others, however, is the use of a European military belt as its strap.

The iron belt buckle on the strap is likely French or English in origin. While the story of how the maker of this bag acquired the belt has been lost, one can imagine how these items might have changed hands in the context of French and Native American interactions during this period. The intention of the individual who sewed together these disparate pieces is also unknown. Was the action practical or was it an overt political statement?

1.4. Eighteenth-century smoked leather pouch embroidered with porcupine quills and moose hair. European military belt used as strap, probably Iroquois. Courtesy of President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 67-10-10/301.

This hybrid object is just one example of the kinds of thoughtful manipulations of material objects that occurred in the colonial period.

If this bag had been recovered from an archaeological context, it would be unlikely that any leather would have remained, much less the detailed embroidery. In that case, would we have lost some of the intricate meanings that were invested in this composite object? Possibly. The interpretive potential this object poses inspires many of the discussions in this book. I wish to move beyond conservative interpretations to more fully explore that diversity of ways that objects of clothing and personal adornment were used to create, verify, and manipulate different identities throughout colonial America.

In the next chapter, I briefly outline artifacts of clothing and adornment found within the archaeological record. As other volumes identify and describe artifacts related to clothing (e. g., Deagan 2002; White 2005), here I describe just a few examples from the diverse range of objects of clothing and adornment available to people living in colonial North America. I do this not as a sourcebook for identification but rather as a way to understand methodological approaches used to interpret items of clothing and adornment within historical archaeology. I also include a discussion of practices that are rarely found in the archaeological record, such as tattooing, which must be considered when taking into account the adornment of the colonial body.

Following this I turn to case studies in North America and utilize archaeological, ethnographic, archival, and visual sources to investigate how people put together fashions through new and familiar forms of material culture to present the body and the self in colonial spaces. Each of the remaining chapters contains narrative - and object-centered vignettes that highlight meaningful intersections of the body, clothing, and adornment during the colonial period. The case studies discussed in these chapters include objects from the Peabody Museum’s collection as well as items and collections from other published works and museum collections.

Chapter 3 provides a discussion of clothing artifacts related to the enclosures and alterations of the body, which include fasteners such as shirt buttons and lead seals attached to bales of cloth as well tattooed skin, another kind of enclosure. I follow this chapter with one that looks at adornment or objects that can be attached to the body or clothing, such as pierced coins, crucifixes, and glass beads. Chapter 5 provides a discussion of two assemblages of artifacts of clothing and adornment recovered from different

Parts of colonial North America. The ways that people used the objects of clothing and adornment in these assemblages in dressing practices were more varied and creative than those imagined by the manufacturers and suppliers of those items. The examples in this chapter consider the extent to which colonial individuals mixed different kinds of clothing and adornment in daily life.

I conclude the volume with a discussion of some current overarching themes and suggestions for future directions in the study of clothing and adornment in historical archaeology. Dress, clothing, and adornment played a central role in constructions of colonial American identities; and influenced dress in later centuries, including the Victorian period and beyond. The archaeological record provides insight into the ways that different peoples used clothing and adornment to make social statements, resulting in diversity of clothing and personal adornment found throughout colonial America.

World History

World History