Direct evidence for what people ate in the past is extremely rare but under certain circumstances human fecal material survives in archaeological contexts and can be analyzed. Within the broad definition of ‘fecal remains’, three distinct classes can be recognized. Sewage (often referred to as cess) is recovered from cesspits, latrines, sewers, and drains, and provides large, mixed assemblages of human feces together with waste from the kitchen and elsewhere. Where preservation is good, particularly under waterlogged conditions, microscopic analysis of such assemblages has provided valuable information on diet and living conditions. The mixed nature of the samples makes it difficult to comment on individual meals, but the inclusion of other household waste products and evidence for sanitary practices in many ways compensates for this.

By contrast, coprolites (preserved human stools) or the contents of the intestines of well-preserved humans are of more value for a study of individual people and the meals that they ate. They are essentially uncontaminated and each sample potentially provides information on not more than one or two meals.

Coprolites are occasionally preserved by charring or mineralization but most commonly survive as desiccated samples in caves or extremely arid areas. In some instances, specified latrine areas are set aside by a settlement and large numbers of broadly contemporary samples can be recovered. Each sample provides evidence for foods eaten by an individual but, as a group, such assemblages also enable the identification of patterns of consumption within populations. The aridity required for the preservation of desiccated samples often means that human encampments within these areas are transient and seasonal. The evidence from coprolites is therefore important for deducing not only the resources exploited but also the season of occupation. There are numerous published analyses of coprolites from the deserts of Southwestern North America, Mexico, Peru, and Chile, or dry cave environments in more humid zones.

When preservation permits, and where no elaborate mummification procedures have been performed, in situ food residues can survive in the intestinal tracts of human cadavers. In areas such as Egypt and the Pacific coast of South America or in dry cave environments, preservation of whole humans by desiccation can occur (see Osteological Methods). Less frequently, bodies are preserved by freezing or freeze-drying, most notably the Greenland mummies or the Tyrolean iceman, or by waterlogging as in the case of European bog bodies. Because these finds are so rare they cannot be considered as being typical of the population at large and are often of limited value when discussing wider dietary issues. However, the presence of the associated corpse and the information that this provides enables a different level of discussion. The person may have died naturally or been killed by force or accident. Fecal analyses can therefore provide information regarding such things as the nature of their last meals, whether they had been involved in predeath rituals or subjected to treatments for illness. They may have been given food that was only fit for the poor or prisoners. In the absence of written accounts this type of information is very difficult to unearth by any other means.

As archaeological assemblages, coprolites and gut contents contain a very diverse range of biological and mineral components. This makes it difficult for any one specialist to undertake all elements of analysis. Desiccated samples usually require rehydration using an aqueous solution of tri-sodium phosphate. This solution restores much of the original texture and pliability to both animal and vegetable tissues, enables samples to be teased apart and individual items extracted for identification. Much of the initial work requires detailed light and electron microscope analysis to identify the more obvious components but chemical analyses of the finer residues may, in the future, offer the potential for the identification of part digested foods or their waste products. Other more specialized techniques such as electron spin resonance can be used to determine how particular food items have been cooked.

The most productive area for research is in the analysis of food elements that are totally or partially resistant to digestion or have escaped digestion by

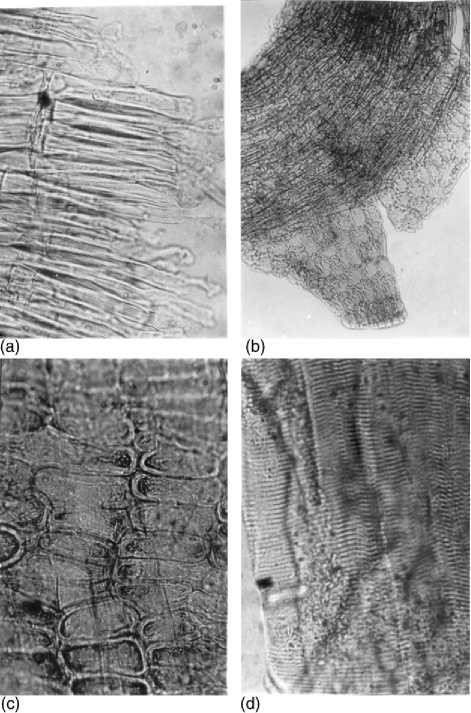

Figure 1 Light micrographs. a, Cells from the seed coat of a legume species from a mummy from Azapa, North Chile. Magnification X 290. b, Seed coat of an Opuntia cactus seed from a coprolite from Tulttn, N. Chile. Magnification x 45. c, The bran of rye (Secale cereale) from the gut of the Huldremose bog body, Denmark. Magnification x 290. d, Meat fibers taken from a coprolite from Tulttn, N Chile. Magnification x 290.

Being protected from the digestive enzymes in some way. Fibrous or resistant parts of plants such as cereal bran, epidermal fragments, and certain seeds are commonplace and with the correct reference material to hand can be identified (Figure 1). Even starch grains can survive and be identified under certain circumstances. Traces of animal foods are also restricted to the more robust body parts, so hair, bone, insect, and crustacean parts are commonly Identified. Muscle fibers have been recovered on occasion, but traces of commonly eaten foods such as milk or blood products, eggs or softer body parts do not survive in a readily identifiable form (Figure 1).

The remains of foods are often accompanied by evidence for pathological conditions such as intestinal parasites or their eggs, and other inadvertent inclusions can add significantly to our understanding of how people lived. Insects or other invertebrates such as mites can inform us about storage conditions, and the pollen breathed in or ingested with food and drink can provide evidence for the season in which the food was consumed. Traces of grit and the fragmentation of remains can throw light onto the grinding/pound-ing implements used to process food and the presence of burnt food and charcoal about cooking techniques. The foods and the preparation techniques used can also say a lot about the wealth or status of an individual and the nature of trade. In some instances they enable a discussion of such things as ritual meals or famine foods.

See also: Archaeoparasltology; Archaeozoology; Frozen Sites and Bodies; Paleoethnobotany; Seasonality of Site Occupation.

World History

World History