The long Archaic period, beginning sometime after 9000 bc, can be divided into Early, Middle, and Late subperiods (see Figure 1). Comparable to the Old

World Mesolithic, it was a time of profound transformation, culminating in the appearance of permanent settlements supported by a subsistence economy primarily based on agriculture. In Middle America domesticated animals - and only the turkey, Muscovy duck, dog, and honeybee can be included in this category - never figured significantly in the PreColumbian diet. Maize, beans, and squash, three of the early plant domesticates, became Middle America’s staple foods, although by the sixteenth century, when the Spanish arrived, over forty other cultivated species were being consumed.

In Middle America’s highlands the first steps toward agriculture can be traced to the Early Archaic, when wild plants appear to have become an increasingly important component of the diet. At this time populations settled into more defined territories, replacing a mobile lifeway with scheduled rounds of shorter moves to take advantage of the seasonal availability of locally available plants and animals. By the Late Archaic, in some highland regions, particularly where resources were sparse, ‘foraging’ of this kind gave way to a ‘collecting’ strategy, where small task groups made transient forays to specific food sources, leaving the main community behind in more permanent settlements. Food collecting strategies may have developed in lowland regions as well, although there is not yet enough evidence to be certain.

The practice of food collecting promoted cultivation when non-local plants were brought back to the settlement where they could be watered, weeded, and better protected from predators. In addition, accidentally dropped seeds from wild food plants would have sprouted in the disturbed soils around the camp. From there it was only a short step to creating domesticates by selecting seeds, cuttings, and issue from the most productive cultigens. The resulting domesticated plants (see Plant Domestication) addressed human needs, but often at the cost of their ability to survive in the wild. Once agriculture was fully embraced, it permitted (some prehistorians would argue that it required) those of its practitioners who were not already doing so to forego their mobile lifeway. Contrasted to subsistence dependent on a finite supply of wild plants and animals, the intensifiable nature of horticulture allowed for the support of densely populated villages and, eventually, for the large towns and cities that appeared in later periods.

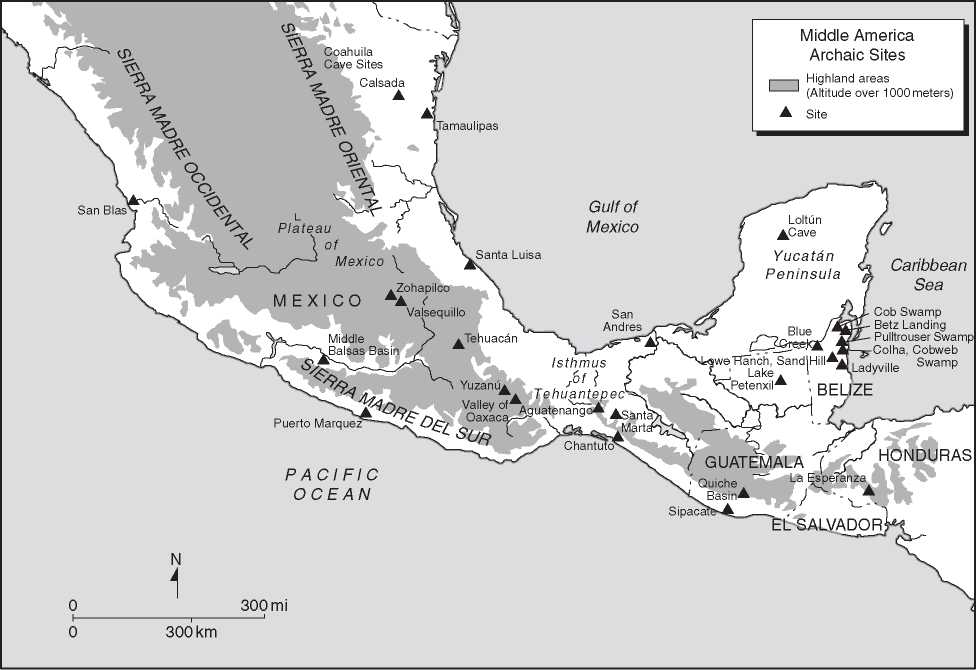

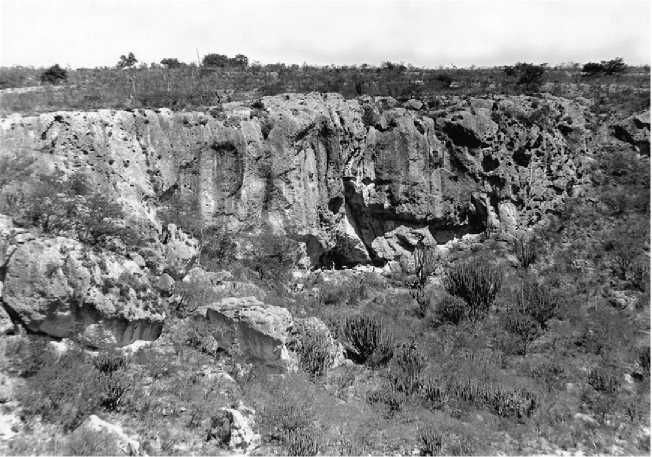

The Archaic transformation in Middle America was not uniform, but varied in timing and possibly in process from region to region. Like the previous Paleoindian period, most of what we currently know about it derives from investigations in highland regions where the more arid environment is more conducive to preservation. Practical difficulties of research in the hot, often wet and densely forested, lowlands of Middle America are exacerbated by the three-meter post-Pleistocene rise in sea level that has inundated early coastal sites; by higher groundwater levels and encroaching wetlands that frustrate excavation; by stream and river erosion that has destroyed some sites while deeply burying others under alluvial sediment; and by a paucity of cave sites where archaeological remains tend to be better preserved (Figure 8).

Only in the last few decades has this unbalanced perspective begun to be rectified, often through sophisticated collection and analytical techniques. Even so, almost nothing is known about the lowland Early Archaic, particularly in the more interior tropical forest regions, although from evidence of Paleo-indian occupation it could be inferred that at least some of these places were inhabited. The emerging picture from the better known lowland Middle and Late Archaic suggests that the path its inhabitants took to a horticulture-based economy was, with the possible exception of tropical domesticates such as manioc, conditioned by earlier developments in the highlands.

The Early Archaic

To fully appreciate the changes that occurred during the Archaic, it is instructive to first examine their earliest manifestation on Middle America’s northeastern periphery. There, at Frightful Cave, Fat Burro Cave, and Nopal Shelter in Coahuila and Calzada Rock-shelter in Nuevo Lecon, a Mexican extension of the North American Desert Culture has been found. Beginning as early as 9000 bc, these caves, and undoubtedly many others in this harshly rugged area, were occupied seasonally by small bands of mobile foragers who left behind a bountiful array of artifacts. Utilitarian items included small, percussion flaked projectile points for attachment to darts propelled by wooden atlatls, along with stone scrapers, choppers, hammer-stones, fiber cordage, sandals, baskets, mats, fire drills, and tongs. Hinting of a rich ceremonial life were scarifiers for bloodletting or tattooing, musical rasps, ornamental shell beads, and hallucinogenic plants. Food remains, some recovered from grass-lined storage pits, indicate a diet heavily dependent on wild plants, supplemented by meat from small and medium sized animals of modern species. Cobblestone manos (grinding stones) along with fragments from flat milling bases for

Figure 8 Map of Middle American Archaic sites mentioned in the text.

More efficient processing of seeds and other plant parts were used for the first time by people who retained a nonagricultural subsistence regime but who showed an increasing interest in plant foods.

Further south, in the Sierra de Tamaulipas, the lowest, ‘Infiernillo phase’ excavation levels at several cave sites dated c. 7000-6000 bc reveal an Early Archaic artifact inventory similar to that of the Desert Culture, including a food complex that relied primarily on wild plants such as runner beans, agave, and opuntia. A critically important distinction was that by the end of the Archaic period, at around 2400 BC, maize (Zea mays) was being cultivated. The discovery, first published in 1958, but with a now corrected sequence of dates, stimulated a still ongoing search throughout Middle America for earlier places of plant domestication. A number have been found, among them the Santa Marta Rockshelter and Aguacatenango II-III in Chiapas, Mexico, some surface surveyed locations in Guatemala’s Quiche; Basin, and a series of habitation sites near La Esperanza, Honduras. However, to this day, much of what has been learned since the Tamaulipas project has been a product of investigations in just three highland regions: the Tehuactin Valley, the Valley of Oaxaca, and the Basin of Mexico.

From the Tehuactin Valley, information about the Archaic derives from the Tehuactin Archaeological-Botanical Project, previously noted for its Paleoindian period research. Several hundred cave and open-air archaeological sites were surveyed, nine of which were chosen for excavation. Along with the many artifacts, copious food remains were recovered, including both macrobotanical specimens and human coprolites (fossilized feces). Based on their stratigraphic position and the typology of artifacts, the materials were originally assigned to one or another of three sequential Archaic phases, El Riego (70005000 bc), Coxcatliin (5000-3400 bc), and Abejas (3400-2000 bc), mirroring the division of the Archaic into Early, Middle, and Late subperiods. Although the specific dates assigned the excavated materials and their cultural implications have been extensively amended since the 1960s when the project took place, the general sequence of developments is still widely used to model the transition from hunting and gathering to horticulture in highland Middle America.

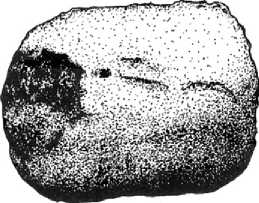

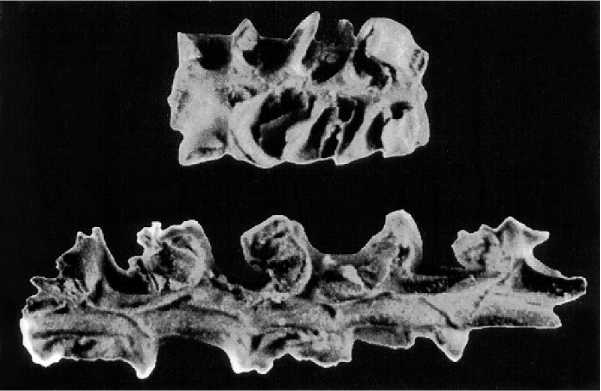

The earliest Archaic food plants recovered from the Tehuactin excavations consisted exclusively of wild species such as foxtail millet, mesquite, and acacia, from which seeds and pods were harvested; pochote, which has edible roots and seeds; maguey leaves and hearts, collected for roasting; and chupandilla, cosa-huico, ciruela, and opuntia (prickly pear), desired for their fruit. Along with the appearance of manos and metates - the grinding stones and basins that were to become the ubiquitous plant processing tools in Middle America - the food remains indicated the increasing importance of plants in the diet of the Tehuactin foragers (Figure 9).

By 7000 BC, the first tentative step toward plant domestication at Tehuactin was taken in the form of attention the Valley’s Archaic foragers paid to avocados (Persea americana). Because these trees required regular watering, they appear to have been transplanted to locations where they could be better tended, a procedure amounting to simple cultivation. By 5960 BC, toward the end of the Early Archaic period, morphologically domesticated squash (Cucur-bita pepo) was being cultivated in the Valley; by 5200 BC there is evidence for the domesticated bottle gourd (Lageneria siceraria); and somewhat later, chile peppers (Capsicum frutescens).

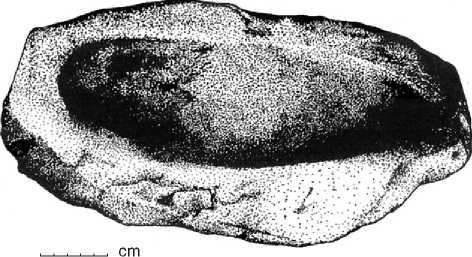

Some tiny fossilized maize cobs from the Tehuactin caves were also determined to be domesticates, as it was observed that they were unable to disperse their tightly attached seed grains without human assistance. The survival of this maladaptive morphology could only have been the product of purposeful selection for a set of genetic traits that made the plant more attractive for harvesting and consumption, but which had the effect of preventing its reproduction in the wild. Charcoal from the archaeological strata in Coxcatliin Cave from which the primitivelooking cobs were recovered was radiocarbon dated

Cm

Figure 9 Archaic period oblong mano fragment (above) and metate-mWWng stone from Tehuacfin.

Figure 10 Maize cob remains from Tehuacfan. From left to right: Middle Archaic CoxcatlEin phase; Late Archaic Abejas phase; Late Formative/Early Classic; last two on the right date to the Postclassic period. Photograph courtesy of the R. S. Peabody Museum of Archaeology, Phillips Academy, Andover, MA.

C. 5500 BC and until recently that terminal Early Archaic date was accepted as marking the initial domestication of maize in Middle America (Figure 10). Recent analysis of bottle gourd samples from the same level at the cave verified their domestication at a date just a few hundred years later. However, subsequent direct AMS determinations on maize cobs from the Valley’s San Marcos and Coxcatliin caves, produced a suite of revised dates, none earlier than 3555 BC, well into the Middle Archaic. Consequently, most archaeologists now reject the original 5500 BC date, attributing it to post-depositional intrusion of the cobs into earlier stratigraphic levels of Coxcatliin cave.

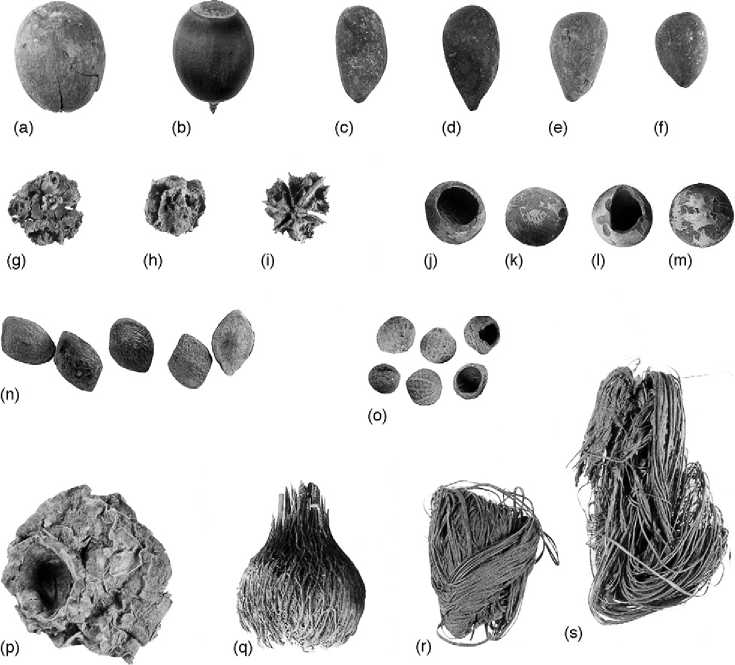

Excavations at Guila Naquitz and Cueva Blanca, two cave sites in the Valley of Oaxaca, have greatly augmented the Tehuactin archaeological record. At Guilt! Naquitz (Figure 11), nine AMS determinations on seeds and fruit stems of squash (C. pepo) indicate that a domesticated variety was being cultivated by 8000 BC, over 2000 years prior to the Tehuactin specimen, making it Middle America’s earliest dated domesticated plant. Domesticated bottle gourds (L. siceraria) followed shortly thereafter at 7970 BC Nevertheless, the more than 20 000 plant specimens recovered at the site reflect an Early Archaic diet consisting mainly of wild plants. Acorns appear to have been most important, but runner beans, maguey, seeds and pods of mesquite, prickly pear cactus leaves and fruit, pifion and susi nuts, hackberries, and onions were also among the wild plants eaten (Figure 12). In addition, faunal remains show that deer, cottontail rabbits, mud turtles, collared peccary, raccoons, and a variety of birds were hunted by the small family bands that occasionally occupied the cave during fall seasons.

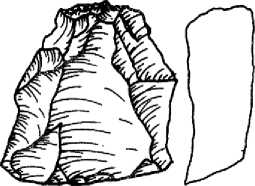

Flaked stone tools, classified as belonging to the Early Archaic Naquitz phase in the Oaxaca Valley, show little standardization. Among them are crude blades, notched flakes, and denticulate scrapers, typically produced from locally available chert (Figure 13). Metates and manos for processing plant foods were made from local ignimbrite and stream-borne cobbles.

Figure 11 Guila Naquitz Cave. A person is standing in front of the cave entrance. Photo courtesy of Kent V. Flannery and Joyce Marcus, Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan.

Figure 12 Wild plant food remains from Guiia Naquitz Cave. a-b: acorns; c-f: pinon nuts; g-i: West Indian cherry seeds; j-m: yaksusi hulls; n: mesquite seeds; o: hackberry seeds; p: prickly pear cactus fruit; q: wild onion bulb; r-s: chewed agave fiber quids. Photograph courtesy of Kent V. Flannery and Joyce Marcus, Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan.

(b)

(a)

Figure 13 Early Archaic period stone tools from the Oaxaca Valley. a: notched flake; b: denticulate scraper; c: crude blade. Redrawn from K. V. Flannery (ed.), Go//a' Naquitz. Archaic Foraging and Early Agriculture in Oaxaca, Mexico.

(c)

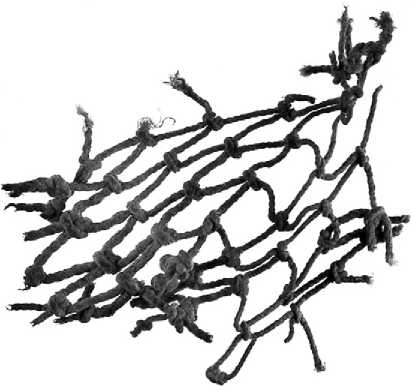

Figure 14 Net bag fragment from Guiltt Naquitz. Photograph courtesy of Kent V. Flannery and Joyce Marcus, Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan.

Knotted netting fragments, cordage, coiled basketry, fire drills, a drill hearth, and some roasting sticks round out a typical Early Archaic artifact assemblage (Figure 14).

The Middle and Late Archaic in the Highlands

The Middle and Late Archaic were times of growing reliance on horticulture among the highland populations of Middle America. At Tehuactin, coyol palms and sapote trees, like avocados, alien to the region, were brought into the Valley and domesticated. Other domesticated plants were two additional varieties of squash (C. moschata and mixta), bottle gourds, common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris), and, as indicated above, maize. By the Late Archaic, tepary beans (P. acutifolius) and jack beans (Canavalia ensiformis) were added to the list. Toward the end of the Archaic, maize, initially a primitive grass of marginal food value, had evolved into a nutritious and storable grain staple.

In the Oaxaca Valley increasing residential permanence is inferred from Gheo-Shih, a Middle Archaic open air camp where occupation has been dated c. 8600 years BP Excavation at the 1.5 ha site revealed an unusual architectural feature interpreted as a ‘dance ground’, similar to those found among historic period Great Basin hunter-gatherer bands. The feature consists of two parallel rows of boulders, twenty meters in length, bounding a seven meter-wide space that had been kept clean of the projectile points, grinding stones, scrapers, pebble ornaments, and other lithic remnants of occupation found elsewhere at the site. Gheo-Shih appears to have been an encampment where several family microbands, totaling 25-30 individuals, congregated for ceremonies and other social activities during the rainy season, when food supplies were ample. Still lacking was a food source adequate to enable year-round residence.

That the occupants of the Oaxaca Valley had begun to experiment by the Middle Archaic with the cultivation of maize has been confirmed by a series of direct AMS dates on some primitive-looking but domesticated cobs from excavations at Guilii Naquitz Cave (Figure 15). The dates, averaging 6250 calendar years ago (approximately 4250 BC), are the earliest currently recognized for domesticated maize, predating by as much as 800 calendar years the oldest Tehuaciin specimens. The absence of wild maize in

Figure 15 The two oldest maize cobs in the New World, from excavations at Guiltt Naquitz Cave, dated c 6250 calendar years ago. The lower cob is approximately 2.5cm long. Photo courtesy of Dolores Piperno, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

Deeper excavation levels at the site has led to the conclusion that the initial place of maize domestication lay outside the Oaxaca Valley. Currently favored is the region around the middle Balsas River Basin, in the states of Guerrero and Michoactin, where DNA and isozyme studies point to a local variety of teosinte (Z. mays ssp. parviglumis), a wild annual grass with naturally disarticulating grains, as the probable ancestor of domesticated maize.

Indications of a continuing movement toward residential permanence in the Oaxaca Valley appear at the Late Archaic Cueva Blanca site, near present-day Mitla. From artifacts and faunal remains it appears that the seasonal inhabitants of the rockshelter were all-male deer hunters. Whereas the previous foraging lifeway had entailed an annual cycle of movement requiring entire bands to travel from one seasonally available food source to another, a ‘collecting’ strategy is inferred from the Cueva Blanca remains. Under this strategy, deer hunters, as well as other small task groups, made transient forays from a semi-permanent base to specific locations of food and other resources, camping temporarily at places like Cueva Blanca.

An alternative path to highland sedentism that circumvents the transitional collecting strategy was theoretically possible in regions of rich, locally available resources. Zohapilco, in the highlands of Central Mexico not far from the Paleoindian Tlapacoya encampments, may exemplify this alternative. Its setting on the shore of Lake Chalco, surrounded by abundant wild plant and animal populations, is thought to have enabled Zohapilco’s Middle Archaic inhabitants to remain in one location throughout the year. The limited archaeological excavation, consisting of a single long trench, failed to expose evidence of permanent structures, so the actual nature of occupation remains to be verified. Excavation strata, dated 5059-4250 bc, revealed pollen and seeds from wild plants such as teosinte, amaranth, portulaca, goosefoot, tomatillo, and squash, along with the bones of fish, waterfowl, deer, rabbits, turtles, snakes, and the amphibian axolot. With the exception of dogs, there is no evidence of domestication. The associated lithic assemblage included obsidian projectile points and flakes, large bifaces, macroblades, notched flakes, scrapers, mullers, and metates. Not until the Late Archaic do domesticates appear at Zohapilco, in the forms of maize, amaranth, tomatillo, pumpkin, chile pepper, and chayote. Elsewhere in the highlands of Middle America there is no indication at present of permanent, year-round villages until the beginning of the Formative/Preclassic period.

The Lowland Middle and Late Archaic

Future archaeological investigation will be required to determine whether the lack of evidence for Early Archaic occupation in the lowlands of Middle America is simply a failure of discovery or, less likely, whether those regions had been abandoned by their previous Paleoindian inhabitants, only to be resettled thousands of years later. Although this remains an open question, research in coastal and near coastal regions is at least beginning to cast light on the subsequent Middle and Late years of the Archaic. During that time plant domestication and farming spread throughout much of the area and, at the end of the period, permanent villages were established. Whether lowland village life arose without the support of horticulture, as some scholars have argued, or was tied to a developmental sequence that ran from foraging to collecting, and finally to horticulture, as exemplified by the Valley of Oaxaca, is another debated question.

A sedimentary core drawn from a small freshwater lake at San Andriis, near the Gulf Coast of Tabasco, Mexico, was aimed, in part, at addressing this issue. Pollen in the core sediment indicating the appearance of domesticated maize along with forest clearance, presumably for agriculture, was initially dated c. 5000 bc The C14 dates were obtained from fossil clams, which appeared at the same level in the core as the maize pollen and were therefore assumed to be contemporaneous with it. This would have put the development of agriculture long before any known permanent settlement in Middle America. Doubt about the date was cast by the subsequent AMS analysis of another sedimentary core from the adjacent Veracruz coastal plain. In this sample the maize pollen itself was analyzed, producing a date c. 2500 BC, 2500 years more recent than the Veracruz determination and over 1700 years later than the highland Oaxaca domesticated maize cobs. The discrepancy in the two Gulf Coast dates has been attributed to soil bioturbation in the Tabasco core, resulting in a flawed association between the clams and maize pollen. The Veracruz date is corroborated by another pollen sequence from the nearby Tuxtlas region. Together these dates support the hypothesis that maize was initially domesticated in the Balsas Basin, then diffused to a number of highland regions, and only later spread to the lowlands. The small number of archaeological sites currently providing evidence of early plant domestication, however, makes any model of diffusion very provisional.

A lowland site whose inhabitants appear to have lacked an early interest in horticulture is located on the northern Veracruz coast. At Santa Luisa, where occupation seems to have been comprised of multiple deltaic island encampments, the resource rich coastal habitat apparently was the source of subsistence. Plant remains are missing from the Middle-Late Archaic Palo Hueco phase, dated 4000-2400 bc, nor were there any of the grinding implements commonly used for plant processing. Scatters of fire-cracked cobbles are thought to have been used in cooking the oysters, fish, land crabs, and small mammals whose remains were found in abundance. Obsidian nodules, obtained from a geological source several hundred kilometers away in Quersitaro, along with locally available sandstone, served to produce crude blades, flakes, and bifaces, probably used in food preparation. The evidence of Middle Archaic obsidian procurement at Santa Luisa is an indication that long-distance contacts had been established with the highlands.

Although the concentration of nearby resources and density of food remains at Santa Luisa led the site’s investigator to describe it as a ‘permanent village’, it is equally likely that occupation was only seasonal, by foragers making their annual food gathering rounds, and later as either base or satellite camps for people engaged in a system of food collecting. If the latter, it remains to be determined if and when more inland sites within the system engaged in horticulture.

Further insight into the relationship between lowland horticulture and settlement might be drawn from a more comprehensively studied cluster of Middle and Late Archaic sites on the Pacific coast of Chiapas, Mexico. The inhabitants of these sites, known as the Chantuto people, were probably collectors who exploited the lagoon estuarine environment from inland base camps. Six of the sites consisted of massive shellmounds, and at Cerro de las Conchas, the earliest of them, a series of radiocarbon dates brackets occupation between 7500 and 5300 calendar years ago (c. 5500-2300 BC), squarely within the Middle Archaic. Excavation indicated that the site consisted of accumulated refuse from consumption of the marsh clams (Polymesoda radiata) that grew in abundance in the lagoon estuarine environment. Aside from the voluminous burned and unburned clamshells, the limited cultural remains were comprised of waterworn cobbles, believed to have been heated by the Chantuto inhabitants to boil or steam clams, along with ark shells (Anadara spp.) that served as multipurpose cutting and scraping tools. No evidence of plant use was found dating to the site’s Middle Archaic occupation.

Tlacuachera, the largest of the Chantuto shell-mound sites, was dated to the Late Archaic, although occupation may have begun earlier, as excavations never reached the bottom levels of debris. The mound consisted mainly of layer upon layer of burned and unburned shells, the litter from years of clam consumption. Excavation within one of the bedded layers uncovered a clay floor, estimated to have measured 24 by 48 m, with a thickness of 10-20 cm. The labor investment in transporting the large quantity of clay to the site would have been substantial. Nevertheless, the untrampled clamshells suggest that the encampment was not occupied for extended periods of time. A pattern of postholes on the floor marks the location of two oval-shaped structures that may have served as temporary shelters. Although no supporting evidence was found, the investigator proposed that another activity at the site might have been the drying of shrimp, a practice common along the coast today.

(a)

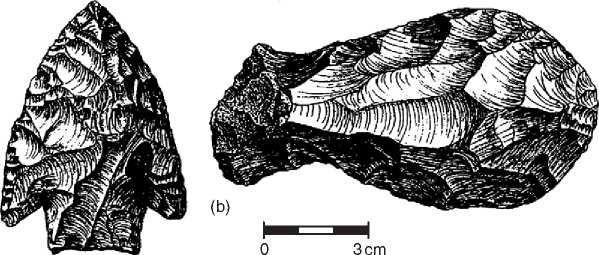

Figure 16 Late Archaic/Early Formative lithic artifacts from Pulltrouser Swamp, Belize. a: Lowe/Pedernales-like projectile point, C14 dated 2210 BC; b: constricted/sole-shaped uniface, C14 dated 1275 BC Drawings courtesy of Mary D. Pohl, Department of Anthropology, Florida State University.

Phytoliths from plants indicating forest clearance as well as from maize were dated c. 3500 BC at Tlacuachera. With regard to maize, stable-carbon-isotope analysis of bone samples from two human skeletons buried in the clay floor stratum suggests that by 2000 BC it was making a substantial contribution to the Chantuto diet. From the lowest cultural level at Vuelta Limton, another Chantuto site located some 20 km inland, phytolith analysis broadens the evidence for a gradual Late Archaic adoption of maize farming in the region. Several hundred kilometers southeast, on the Pacific coast of Guatemala, near Sipacate, fossil maize pollen from a sediment core echos the Chantuto findings. Other Late Archaic sites have been identified on the Pacific coast northwest of the Chantuto region at Puerto Marquez, Guerrero and San Blas, Nayarit; a number of shellmound sites in Sinaloa and Sonora may also date to this period.

On the opposite coast of Middle America, an effort to reconstruct a comprehensive picture of cultural change, from Paleoindian hunting and gathering through the introduction of agriculture and settled village life, was initiated in 1980 by the Belize Archaic Archaeological Reconnaissance. The BAAR project was envisioned as a companion to the Tehuacan Archaeological-Botanical Project under the premise that lowland and highland cultural developments would have followed similar paths. During four field seasons, about 150 possible preceramic sites were recorded, several of which were selected for excavation. With few samples recovered for radiocarbon analysis, a provisional chronology of developments, spanning the years from 9000 to 2000 BC, was constructed by cross-dating projectile points and other lithic artifacts with better known equivalents from other regions.

Subsequent investigation at other sites in the Belize region, primarily through the Colha Project, has shown a number of the BAAR artifact assignments to be erroneous. Lowe projectile points and adze-like constricted unifaces, for example, originally employed to identify the Early Archaic, are now known to have been produced much later in time, with specimens radiocarbon dated at 2210 BC and 1275 BC, respectively (Figure 16). Consequently, there remains a long gap in knowledge about cultural developments in the Belizian lowlands, extending from the end of the Paleoindian period until the final centuries of the Middle Archaic.

The known sequence of development in Belize resumes around 3400 BC, when remains of domesticated maize and manioc (Manihot esculenta) are found in the northwestern part of the country at the Blue Creek site, corresponding in age to the earliest Chantuto evidence. Additional radiocarbon dates from Kob Swamp, adjacent to the Hondo River, reveal maize and manioc there at about the same time. At Cobweb Swamp, near the archaeological site of Colha, manioc pollen is reported c. 2500 BC. There is also evidence throughout the region of deforestation, probably to clear land for agricultural use.

World History

World History