1 Provenience. Table A1.1 (site 19) shows that we examined a total of 168 pieces, making the Okladnikov assemblage 1.9% of our total study of 8813 pieces. Our sampling of the Okladnikov faunal collection was carried out in 1999, 2000, and 2003 at the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, Novosibirsk. A large portion of our sample has no identifiable-level provenience because of the way it was curated after excavation.

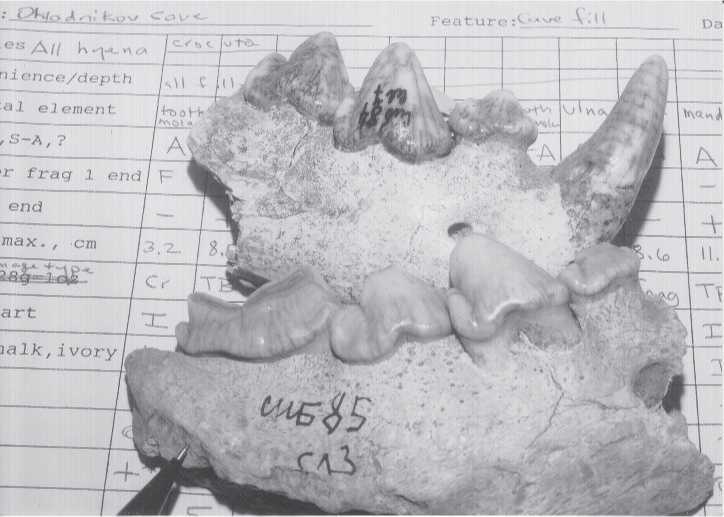

Fig. 3.91 Okladnikov Cave hyenas. Chewed young adult hyena mandible fragments from Layer 3 (1985).

The pencil points to a tooth notch and polishing. The lower piece is 10.5 cm in length. The site was originally named Sibiryachikha after the nearby village. Okladnikov never had anything to do with this site (CGT color Krasnoyarsk 8-3-00:3).

As will be seen, everything we had read in the many archaeological publications dealing with Okladnikov Cave failed to prepare us for the abundant evidence of bone damage by large carnivores, even though the senior author had personally seen carnivore-damaged bone in situ in 1987. Hyenas seemingly used the cave as much if not more so than did the late Pleistocene Mousterian people.

2 Species. The identified bones belonged to animals widely spread in Late Pleistocene timesare: marmot, gray wolf, fox, bear, cave hyena (Fig. 3.91), horse, wooly rhinoceros, reindeer, wild sheep, and bison. There are a few bones that belonged to beaver, red wolf, and cave lion.

Table A1.2 (site 19) shows the near-dozen species that Ovodov could identify in 168 pieces studied in this project. It should be noted that the bone fragments used in this study are generally smaller and much less complete that those used for paleontological species identification. Goat-sheep (16.7%), cave hyena (14.3%), and big mammal (10.1%) are the most frequent groups identified. Indeterminate was our largest class (36.3%). Each of these is more common compared with our pooled assemblage averages. Okladnikov Cave has the highest frequency of rhinoceros of all of our assemblages, and its frequency of hyena pieces slightly exceeds even that found at Razboinich’ya (11.7%). Derevianko and Markin (1992:83) report that hyena remains were recovered fTom Levels 1-6, whereas bear and wolf were not found in some of these levels. Level 7 had only horse and rhinoceros bone (we found also Ovis/Capra). None of our Level 7 had cut marks or burning, but had tooth scratches, dints, and other signs of carnivore damage. We suggest that Level 7 also had hyena presence. Hence, Okladnikov was used by hyenas for most if not all of its stratigraphic history. Although the Mousterian stone artifacts found at Okladnikov Cave (Derevianko and Markin 1992) demonstrate without question that people used the shelter, the continuous presence of hyenas also demonstrates without question that the human occupancy was discontinuous.

The zooarchaeological remains are numerous, there being minimally 6773 elements of large - and medium-sized mammals representing minimally 20 species, each of which is widely distributed in the late Pleistocene of the Altai region. Ovodov and Martynovich (2004) have identified hare (Lepus timidus), cape hare (Lepus capensis), marmot (Marmota baibacina), beaver (Castor fiber), gray wolf (Canis lupus), fox (Vulpes vulpes), red wolf (Cuon alpinus), brown bear (Ursus arctos), badger (Meles meles), cave lion (Panthera spelaea), cave hyena (Crocuta spelaea), horse (Equus cf. caballus), rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis), mammut (Mammonteus primigenius), red deer (Cervus laphus), roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), reindeer (Rangifer tarandus), wild sheep (Ovis ammon), goat, ibex, markhor (Capra sibirica), and bison (Bison proscus). One unexpected faunal identification for Okladnikov Cave was a giant Pleistocene frog (Gutieva and Chkhikvadze 1990).

3 Skeletal elements. Of 168 pieces, the most common Okladnikov skeletal elements are long bone (32.1%) and mandible (8.9%) (Table A1.3, site 19). Unknown elements make up 16.1%. The near-absence of teeth in Table A1.3 is due to our not studying loose teeth unless they evidenced perimortem damage. However, we are unable to explain the near-absence of skull elements as is the case with several of our assemblages. Compared with our pooled assemblage averages, most elements occur in similar frequencies. Although Okladnikov has fewer ribs and more long bone pieces, Okladnikov and Razboinich’ya are remarkably similar in their frequencies of nearly all skeletal elements, so much so that we propose that Okladnikov Cave was occupied as frequently by hyenas as by humans.

4 Age. Of 168 Okladnikov pieces, 8.3% are sub-adult, and 42.9% are adult (Table A1.4, site 19). The remainder are of questionable or unknown age. The Okladnikov sub-adult frequency is nearly identical with our pooled assemblage average, but the Okladnikov adult frequency is less. Age representation at Okladnikov and Razboinich’ya are quite similar.

5 Completeness. Of 168 Okladnikov pieces, 70.8% have no anatomical ends, 23.8% possess one end, and 5.4% are more-or-less complete (Table A1.5, site 19). These values differ somewhat fTom the averages of our pooled assemblage, indicating greater peri-mortem damage in the Okladnikov sample. However, the Okladnikov frequencies are rather like those of Razboinich’ya.

6 Maximum length. We measured 180 Okladnikov pieces, obtaining a mean of 7.9 cm and a range of 2.1 cm to 26.9 cm (Table A1.6, site 19). These and the other statistical values are quite similar to those of our pooled assemblage. Compared with Razboinich’ya, the Okladnikov statistics indicate slightly more size variability, even though the means are very similar. Looking at the Okladnikov upper range limit for goat-sheep and hyena and the undamaged bone lengths for these species provided by Vera Gromova (1950: table 27) shows considerable similarity, although the lower limits are very different.

7 Damage shape. We classified damage form in 655 pieces fTom Okladnikov Cave (Table A1.7, site 19). The sample for this variable is not comparable because it had been pulled out of the larger sample for identifying species.

8 Color. Mostofthe 168 Okladnikov pieces are ivory colored (90.5%; Table A1.8, site

19). The 6.5% pieces of light brown color are most likely soil-stained. They came fTom various layers, both shallow and deep, so color here does not correspond well with time. The 2.4% black colored pieces unquestionably had been burned, as probably was a single black-brown specimen. All of the black or black-brown pieces have perimortem breakage but no sign of carnivore damage. The black specimens include: (1) a 2.9 cm long adult? sheep-goat phalanx from Layer 3; (2) a 5.2 cm long adult?, species?, long bone fragment from Layer 2; (3) a 2.1 cm long adult?, species?, vertebral fragment from Layer 2; (4) a 2.3 cm long adult, species?, long bone fragment from Layer 2. The probably burned brown-black piece is an 8.2 cm long adult?, “big” species, long bone fragment from Layer 3. These five pieces are useful evidence for fire, but not cooking. Because of their small size, we consider them to have burned accidentally at different times by either falling or being discarded in a fire hearth, or having a fire started over them while they were surface trash.

The color ratios are similar to our pooled assemblage values, with Okladnikov having almost exactly the same frequency of ivory colored pieces. Okladnikov differs from Razboinich’ya only in its having black (burned) pieces, which are absent in the latter site.

9 Preservation. Ivory-like hardness characterizes the preservation of the 168 Okladnikov Cave pieces (73.2%; Table A1.9, site 19). The 3:1 ratio of ivory to chalky conditions seems reasonable for a site whose excavation occurred within and outside the protective limestone entrance overhang and interior cave walls. Fully open sites such as Kara-Bom and Ust-Kova have more chalky pieces, while cave interiors such as Ust-Kan have fewer. Compared with our pooled assemblage averages, Okladnikov has a slightly higher percentage of chalky pieces. Compared with Razboinich’ya, Okladnikov has more chalky pieces. Presumably this means that Okladnikov had a weather-exposed bone-littered fronting talus slope.

10 Perimortem breakage. Almost 95% of the 168 pieces have perimortem breakage (Table A1.10, site 19). Compared with the Shestakovo and Volchiya Griva open mammoth sites with their low 18.7% and 8.0% perimortem breakage, respectively, a lot more human and carnivore processing transpired at Okladnikov Cave. If we assume that perimortem breakage was done by carnivores when the combination of tooth dints, scratches, end-hollowing, or pseudo-cuts also occurs on a piece, then the amount of carnivore bone processing at Okladnikov Cave is almost twice the amount (64.6%; 102/158 pieces) attributable to humans (35.4%; 56/158). This is especially so if we assume that pieces with perimortem breakage, but lacking carnivore damage, resulted from human processing. What’s more, there is carnivore tooth damage on most of the pieces lacking perimortem breakage. Compared with our pooled assemblage average, Okladnikov has more perimortem breakage, but nearly the same as Razboinich’ ya.

The taphonomic inference from the Okladnikov Cave perimortem damage is that the site had an extensive late Pleistocene carnivore presence. Since hyenas are the only carnivores directly identified in our Okladnikov sample, we assume that they did much of the perimortem bone damage. A further implication is, of course, that hyenas were also responsible for the introduction of some portion of the animal remains found in the site. We feel certain that the Okladnikov Cave faunal remains do not represent only the results of human hunting activity. In fact, we suspect that possibly the majority of the animals represented in our sample were brought to the cave by hyenas and probably by other carnivores not identified in our bone and tooth sample, such as cave lions and wolves. This raises a number of questions about site occupancy, including seasonal use by humans and hyenas, periods of human absence from the locality or region, and possible competition between humans and hyenas for use of the cave site and the small valley that it overlooks.

11 Postmortem breakage. Of 168 Okladnikov pieces, 22% have postmortem breakage (Table A1.11, site 19.) This is not much more than our pooled assemblage average (17.8%), which we see as indicating nothing out of the ordinary for the amount of Okladnikov postmortem breakage. Okladnikov has about twice the amount of postmortem breakage compared with Razboinich’ya (10.9%), again not exceptional in our view, given the talus slope context and the rather unmindful method used to transport faunal remains from this site.

12 End-hollowing. Of 166 Okladnikov pieces, 17.5% possess end-hollowing (Table A1.12, site 19). This value is almost twice that of our pooled assemblage average, and more than twice that seen in Razboinich’ya (8.1%). We consider end-hollowing to be a robust indicator of carnivore presence based on its extensive documentation in the taphonomic, forensic, and bioarchaeological literature (Lyman 1994), and on our own casual observations of domestic ranch dog and coyote bone chewing. The Okladnikov Cave sample has 29 examples of end-hollowing. This number includes three adult hyena molar and premolar teeth whose roots have been chewed off - a condition we include with end-hollowing because of its damage-type similarity. The frequency of end-hollowing would most likely be greater if more ends of long bones had remained. Most pieces of bone with end-hollowing also have tooth dints, tooth scratches, or pseudocuts, or all three conditions (96.6%; 28 /29 pieces). Only one (3.4%) end-hollowed piece has no dints, scratches, or pseudo-cuts.

13 Notching. Fracture plane notching occurs in 39.2% of our 168 pieces (Table A1.13, site 19). The number of notches ranges from one (13.2%) to as many as 15 per piece (0.6%). One to two notches is most common. Compared with our pooled assemblage average, Okladnikov has more than two times as many notched pieces. It even has more than Razboinich’ya (23.6%).

In our pilot study of the Razboinich’ya hyena cave assemblage, we were quickly struck by the frequent occurrence of notching. These numerous pieces suggested that notching was an important characteristic of the powerful bone-cracking capability of these animals. Relative to the very small amount of carnivore damage that can be identified in our two paleontological mammoth sites (Shestakovo and Volchiya Griva), both of which have almost no notching, we still maintain this view. For Okladnikov Cave, the relationship between notching and undoubted tooth damage (dints and scratches) is strong. Of pieces with notching, 96.6% (56/58) also have tooth dints, scratches, pseudo-cuts, and/ or end-hollowing. Only 3.4% (2/58) of the notched pieces lack dints, etc. Like Razboinich’ya, Okladnikov Cave has so much notching at the edges of fracture planes that we cannot help but infer an extensive hyena presence. We believe that when a bone assemblage has high frequencies of tooth dints, tooth scratches, end-hollowing, and fracture plane notching, that a very strong case exists for carnivore perimortem processing. This is what we conclude occurred at Okladnikov Cave. While numerous stone tools and two human teeth prove without any doubt that humans used the cave in late Pleistocene times, perimortem bone taphonomy shows that carnivores used the cave as well, and possibly even more so than the humans.

14 Tooth scratches. More than half of our 168 Okladnikov pieces have tooth scratches (57.0%; Table A1.14, site 19). The number of scratches per piece ranges from 1 to 105, with higher numbers being 25, 35, 44, and 55. The most frequent number of scratches per piece is more than seven (23.0%), followed by four (9.1%), two (5.5%) and one (5.5%). As might be expected, more scratches are on larger than on smaller pieces. The specimen with 105 scratches was found in Layer 6. It is a 21.5 cm long wedge-shaped flake of an adult? mammoth leg bone. It also has perimortem breakage, 30 tooth dints, two pseudo-cuts, and polishing all over the piece. It may have a chop mark. We noted at the time of study that it “could have been struck fTom the long bone shaft by humans, and later chewed on by hyenas.” We have since come across flakes of similar size and form that have none of the more diagnostic signs of human processing (cutting, abrasions, etc.). Therefore, this large flake’s entire suite of perimortem damage could have been produced solely by a hyena. Compared with our pooled assemblage average, Okladnikov has more than two times the number of pieces with scratches. It also exceeds Razboinich’ya (37.1%) in number of scratches.

15 Tooth dints. As with tooth scratches, the Okladnikov Cave sample has more than half of its 167 scorable pieces exhibiting tooth dints (55.7%; Table A1.15, site 19). The number of dinted pieces ranges fTom those with one (7.8%) to a piece with 70 (0.6%). The most frequent number of dints per piece is more than seven (20.4%), followed by two (9.6%), and one (7.8%). The fragment with 70 dints is a 6.5 cm long goat-sheep metapodial with one anatomical end. It also has end-hollowing, four notches, and six tooth scratches, but, unexpectedly, no definable polishing. Because it was found in Layer 1, the carnivore involved might have been a dog or wolf instead of the ever-suspected Pleistocene hyenas.

Compared with our pooled assemblage average, Okladnikov has more than twice the number of pieces with one or more dints. The Okladnikov dinted piece number is close to that of Razboinich’ya (52.8%).

16 Pseudo-cuts. Unlike other sites in this study lacking pseudo-cuts and lacking osteological or dental evidence of hyenas, the Okladnikov Cave assemblage has 12 examples in the 167 pieces (7.2%; Table A1.16, site 19). The number of pseudo-cuts per piece ranges fTom one (3.0%) to six (0.6%). There are six pieces with either one or two pseudo-cuts. Without exception they all occur on pieces that also have tooth dints, scratches, end-hollowing, or notches. One questionable pseudo-cut also occurs on a piece with tooth dints, notching, and end-hollowing.

Pseudo-cuts are so named because they look very similar to stone tool cut marks. However, at Okladnikov Cave there can be little doubt that pseudo-cuts were produced by carnivore teeth, probably teeth with small newly chipped, burinated cusp tips. When chewing on a bone, the carnivore’s chipped tooth may accidentally produce a groove V-shaped in cross-section, not unlike that left by a sharp stone flake or burin.

Compared with our pooled assemblage average, Okladnikov has a slightly greater occurrence of pseudo-cut pieces. It has almost four times the number found at Razboinich’ya (3.1%). Two possibilities come to mind: (1) We have misidentified pieces with true cut marks as having pseudo-cut marks. (2) There was much more hyena and other carnivore activity at Okladnikov Cave than is reported in the literature of this well-studied site.

17 Abrasions. Abrasions are believed to be caused by the slippage of a bone being broken open on an abrasive anvil, or by a glancing blow by an abrasive hammer stone employed for the same purpose. There are only two Okladnikov pieces out of 167 that have abrasions (1.2%; Table A1.17, site 19). One has only one minute striation, the other has a set of more than 25 minute parallel striations. Each of these pieces also has tooth dints, and none has cut or chop marks that would favor inferring that these abrasions were produced by human bone processing. At Okladnikov Cave, the association between abrasions and carnivores is stronger than that between abrasions and human bone processing. Abrasions alone cannot be used to argue for their human origin at this site.

Compared with our pooled assemblage average, Okladnikov is nearly identical in its frequency of pieces with abrasions. Razboinich’ya, as expected, has fewer examples of abrasions (0.5%).

18 Polishing. Polishing is common in the Okladnikov Cave sample of 167 pieces (73.7%; Table A1.18, site 19). Because it is so strongly associated with other types of bone damage that were undoubtedly caused by carnivore chewing, polishing is considered to be another indication of carnivore presence. This is especially so when polishing occurs on perimortem fractures that are on the end(s) and middle of a bone fragment. There are only four pieces with middle - or middle-and-end polishing that lack carnivore damage. End-polishing alone may also be due to carnivore activity; however, there are more examples that lack such an association (32.3%; 10/31) than is the case for middle - and middle-and-end polishing. Thus, end-polishing alone is not as diagnostic of carnivore damage as are the other forms discussed.

Compared with our pooled assemblage average, polishing of end, middle, and both locations is slightly more common in the Okladnikov assemblage. It is considerably more (73.7%) in Okladnikov than in Razboinich’ya (59.4%).

19 Embedded fragments. There are only six instances of fragment embedding in 168 Okladnikov pieces (3.6%; Table A1.19, site 19). The number of embedded fragments per piece ranges from one to three. Each example is associated with some form or another of presumed carnivore damage. Only one piece with embedded fragments is associated with cut marks, but this piece also has tooth dints, scratches, and notching. Either we misidentified the cut marks, or it is a piece that was processed by both a human and a carnivore agent.

Our pooled assemblage average for notched pieces is nearly the same as Okladnikov. Notched pieces occur twice as often (8.8%) in Razboinich’ya.

20 Tooth wear. There are 18 Okladnikov teeth or tooth-bearing mandible fragments (Table A1.20, site 19). Three have no tooth wear (16.7%), nine have slight cusp wear but no dentine exposure (50.0%), and six cases have dentine exposure (33.3%). All but one of these teeth belonged to hyenas, including all three cases without wear. Adults (47.1%) and sub-adults (52.9%) are about equally divided among the hyena specimens, all of which have perimortem chewing damage done by presumably some other hyena. As we define age by tooth wear, two-thirds were young individuals.

Our pooled assemblage average has fewer young individuals than Okladnikov, a value nearly the same as in Razboinich’ya (36.0%). There is no severe tooth wear (grades 3 and 4) in Okladnikov or Razboinich’ya, and far fewer in our pooled assemblage.

21 Acid erosion (Figs. 3.92-3.93). We consider this form of perimortem damage to be strongly diagnostic of carnivore damage, especially by hyenas when the acid-eroded pieces are large and highly eroded, and when hyena remains are part of the faunal assemblage. Eight Okladnikov pieces out of 168 (4.8%; Table A1.21, site 19) are acid-eroded. Their maximum diameter ranges fTom 2.8 cm to 6.8 cm. One eroded piece is a tooth root of an adult animal of unknown species. Our sample contains eroded pieces from Layers 2, 3, and 6 - that is, throughout most of the late Pleistocene occupation of Okladnikov Cave.

While Okladnikov has somewhat less acid erosion than does our pooled assemblage or Razboinich’ya (7.3%), we nevertheless have no doubt about the cave having been used often, if not mostly, by hyenas.

22 Rodent gnawing. Okladnikov is one of our few sites with rodent gnawing. Two examples were identified in 1.2% of 168 pieces (Table A1.22, site 19). Both specimens came fTom Layer 3, and both were sheep-goat bones - a sub-adult cervical vertebra with no carnivore or human damage, and an adult scapula with extensive carnivore damage.

Compared with our pooled assemblage average, Okladnikov rodent damage is nearly the same, as is Razboinich’ya (0.8%). There are only eight sites with rodent gnawing, half of which are open sites, and half are cave sites.

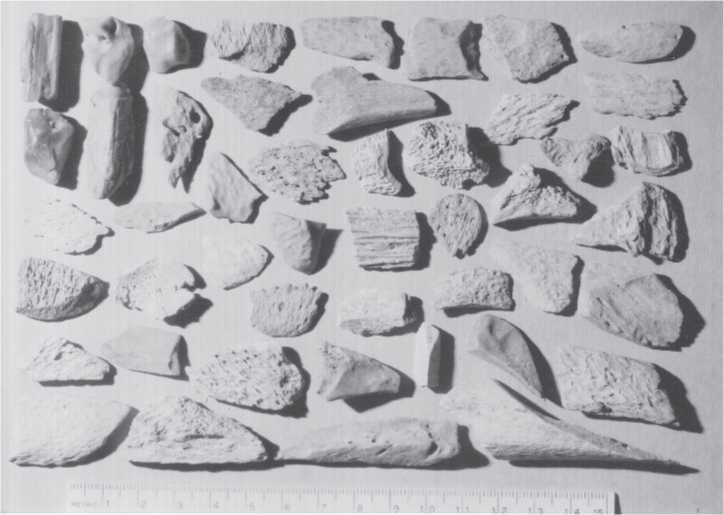

Fig. 3.92 Okladnikov Cave hyena stomach bones. A sample of partly digested bones and teeth found in Layer 6 (1984). Scale is 15 cm (CGT neg. IAE 7-22-99:2).

Fig. 3.93 Okladnikov Cave stomach bone with cuts. This specimen from Layer 6 (1984) is of special interest. There is a small field of seven cut marks on this 3.1 cm long unidentifiable bone fragment that was also eroded and polished. The inference is not only that a hyena had scavenged refuse left in Okladnikov Cave by the Mousterian inhabitants, but that it and they were in temporal and spatial proximity with one another (CGT neg. IAE 7-22-99:9).

23 Insect damage. Like nearly all of our sites, the Okladnikov sample of 168 pieces has no damage that could be attributed to insects.

24 Human remains. No pieces of human teeth or bones were present in our study collection. However, as previously discussed, a few sub-adult bones and five teeth had been found before 1987 and reported on elsewhere (Alexeev 1998, Shpakova and Derevianko 2000, Turner 1990a, 1990b, 1990c, see discussion at end of this section).

Five teeth of Paleolithic people fTom Layers 2, 3, and 7 (Derevianko et al. 1998a; Turner 1990a, 1990b, 1990c) were found amid numerous remains of vertebrate animals in the loose cave sediments. Later, one tooth was lost (Shpakova 2001). It should be noted that factually there were essentially more of the human remains than the mentioned ones. In the catalog made by Ovodov after 1987 the following parts of the human skeleton were listed: (1) a fragment of humerus in Layer 1 under the cap; (2) two fragments of the cranial vault and a fragment of metapodia in the same layer but in the grotto; (3) a fragment of humerus bone, calcaneus bone, and two kneepans in Layer 2 under the cap; (4) a part of femur bone in Layer 3 under the cap; and (5) one tooth root in Layer 7 under the vault of room 1 (Ovodov and Martynovich n. d.).

In the cave uphill from Okladnikov cave, Ovodov made a small test excavation and among the faunal remains found a 15 cm long young human humerus of Pleistocene age without its distal epiphysis. Shallow dints left by teeth of a carnivore or perhaps voles are observable on the well-preserved surface.

25 Cut marks. Ten Okladnikov pieces out of 168 (6.0%) have cut marks (Table A1.25, site 19). The range is fTom two to more than 100 cut marks per piece. Most occur on bone fragments without carnivore damage, but four have both cutting and carnivore damage. The cut pieces in our sample originated from Layers 2 and 3.

Compared with our pooled assemblage average of, Okladnikov has a slightly lower frequency of pieces with cut marks. Razboinich’ya has no cutting.

26 Chop marks. Six Okladnikov pieces out of 167 (3.6%) have chop marks (Table A1.26, site 19). The range is 1-11 marks per piece. All of the pieces with chop marks also have carnivore damage. They were recovered from Layers 2 and 3.

Compared with our pooled assemblage average, Okladnikov has a slightly lower frequency of pieces with chop marks. Razboinich’ya has no chopping.

World History

World History