1 Provenience. Table A1.1 (site 26) shows that provenience information was largely unavailable fTom the faunal storage boxes, although Sub-layers 4 and 5 were most often identified. We understand that this open site was stratigraphically a limited occupation during late Pleistocene times, although the range of carbon-14 dates would not support this inference. The possibility of older and unrelated forest fires leaving charcoal debris may be involved.

2 Species. Table A1.2 (site 26) shows that most of the faunal remains were reindeer (58.1%), followed by horse (30.2%), and one piece each of elk and mammoth. The complete identification of the 116 pieces is due to the relatively small amount of perimortem damage in this assemblage and its intensive earlier study by Ovodov.

3 Skeletal elements. As with species identification, all of the pieces from Ust-Kova could be identified as to skeletal element (Table A1.3, site 26). The absence of vertebrae and ribs is due to their not being saved; however, the absence of skull elements is because we missed finding one or more Ust-Kova storage boxes.

4 Age. Almost the entire Ust-Kova assemblage had been adults in life (95.7%; Table A1.4, site 26). Each of the five sub-adults was a reindeer.

5 Completeness. There is a high frequency of whole bones (11.2%; Table A1.5, site 26), and fragments with one anatomical end (87.1%). There are only two pieces lacking both anatomical ends. These are a 24.5 cm long piece of reindeer antler and a 15.8 cm long piece of reindeer mandible. As discussed elsewhere, the high frequency of whole bones and bones with one intact anatomical end is characteristic of assemblages with minimal carnivore activity.

6 Maximum size. The mean of 117 Ust-Kova pieces is 8.0 cm, the range is 2.9 cm to 28.3 cm (Table A1.6, site 26). Compared with the pooled assemblage values, Ust-Kova is very similar in size. Looking at whole long bone lengths of reindeer and horse provided by Vera Gromova (1950: table 27) shows that the Ust-Kova upper range limit is about the same as the reindeer lower limits, and generally less than the lower limits of horse.

7 Damage shape. This category of information was not collected in 1999 as we were trying at that time to formulate a classification.

8 Color. Ust-Kova, being an open site, possesses almost none of the ivory colored pieces that characterize the color of bone fTom cave sites. Instead, open sites have many more pieces that are brown. Brown pieces make up the overwhelming majority (94.9%) of Ust-Kova, whereas ivory colored pieces (1.7%) are rare (Table A1.8, site 26). The discoloration of open site bones is largely only surficial, but the amount of discoloration or “patina” is probably a useful indicator of subsurface water movement or “Brownian movement.” Contact with dry or even slightly moist soil seems not to discolor bone surfaces to the extent that soil with constant drainage does. Color alone is not necessarily a useful indicator of antiquity, but discoloration is probably a valuable characteristic for estimating bone denaturing, which if extensive makes bone of little use for carbon-14 dating or DNA analysis. Thus, one might be more suspicious of bone dating or a DNA assay fTom Ust-Kova, than fTom Razboinich’ya or Denisova caves.

9 Preservation. Corresponding with color, the Ust-Kova assemblage also has relatively poor bone quality. More than half (65.5%) of the 116 pieces are chalky rather than ivory in hardness (Table A1.9, site 26). This is a much higher frequency of low-quality bone than occurs in cave deposits of comparable age. On the other hand, another late Pleistocene open site assemblage examined for this project, Bolshoi Yakor, has a high frequency of hard ivory-like bone fragments. This good qualify we believe is due to that site having remained frozen throughout the Holocene - up to the time of its recent excavation, which is still in progress (see Bolshoi Yakor). Another difference between cave and open sites, but one that we have not systematically recorded, is the frequent occurrence of root tracks on the surfaces of Ust-Kova bones. Root damage is very rare in cave deposits, where the lack of sunlight limits plant growth.

10 Perimortem breakage (Figs. 3.180-3.182). While perimortem breakage is substantial in the Ust-Kova faunal assemblage (88.8%; Table A1.10, site 26), the amount is relatively low compared to cave sites, especially our carnivore baseline standard, Razboinich’ya Cave. By comparison, Bolshoi Yakor, an open site also with a high frequency of reindeer remains, had only one of 263 pieces without evidence of peri-mortem breakage. Ust-Kova has 13 such pieces (11.2%), suggesting that the Ust-Kova hunters were relatively less frugal or some sampling bias exists due to post-excavation curation and disposal.

11 Postmortem breakage. There is a modest amount of postmortem breakage in the Ust-Kova assemblage (15.5%; Table A1.11, site 26). Most of it, if not all, seems attributable to archaeological recovery. We presume that this is due to the relatively poor preservation of these bones, and the difficulty getting them out of the ground.

12 End-hollowing. Perhaps one of the better means in perimortem taphonomy for hypothesizing carnivore activity is the chewing and cupping damage to bone ends,

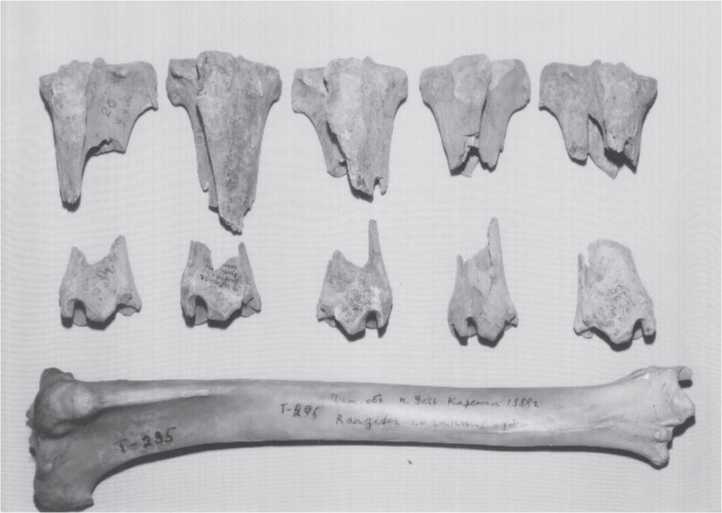

Fig. 3.180 Ust-Kova, bone breakage. Reindeer tibiae with characteristic human damage to long bone shafts but not to ends. Carnivore damage is more often at the softer ends of bones. Awhole modern reindeer tibia is at the bottom to illustrate the amount of breakage to the Pleistocene specimens. The piece in the upper right is 7.5 cm maximum diameter (CGT neg. IAE 8-6-99:2).

Especially when tooth dints and scratches are also present. For what would appear to be a kill site with but brief human occupation, Ust-Kova has a very low frequency of end-hollowing (3.5%; Table A1.12, site 26). However, the four end-hollowed pieces have no associated tooth dints, tooth scratches, pseudo-cuts, or stomach acid erosion. One of the four has associated cut marks. While we feel that carnivores had indeed damaged a small amount of the Ust-Kova bone refuse, we caution that end-hollowing alone is not an absolute sign of carnivore activity, and this caution applies to all other damage types. Hence, the justification for a multi-variable damage signature.

13 Notching. There are two pieces (1.7%) with simple notching - that is, neither is associated with a tool-produced blunt impact on a fracture plane, as are two other notched pieces (Table A1.13, site 26). Inasmuch as there are tooth dints and tooth scratches in this assemblage, one or both of the simple notches could be due to carnivore chewing. However, none of the pieces with notching also has dints or scratches.

14 Tooth scratches. Four (4.3%) of the 116 pieces have tooth scratches. Of these, the number of scratches varies from two to twelve (Table A1.14, site 26). One of the pieces with tooth scratches (n = 12) is a complete adult reindeer astragalus. It also has tooth dints (n = 5). This piece was undoubtedly chewed on by a carnivore, whereas the other three were probably so damaged.

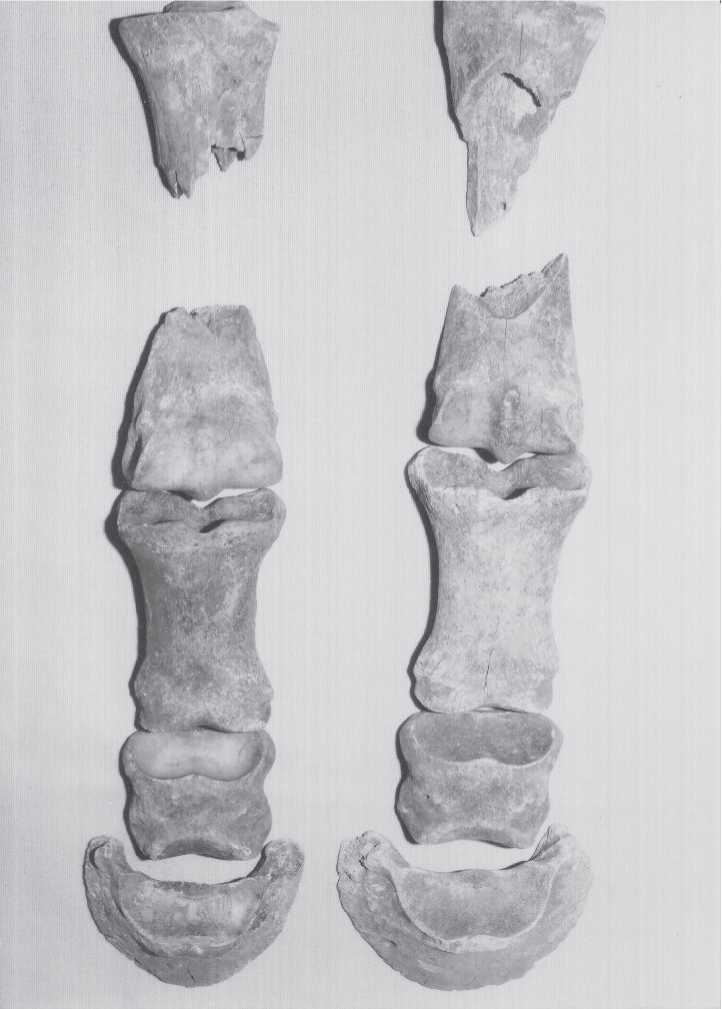

Fig. 3.181 Ust-Kova, bone breakage. Horse metapodial shafts have been broken by humans to

Extract marrow as in previous figure. Lower left toe bone is 8.2 cm in diameter (CGT neg. IAE 8-3-99:26).

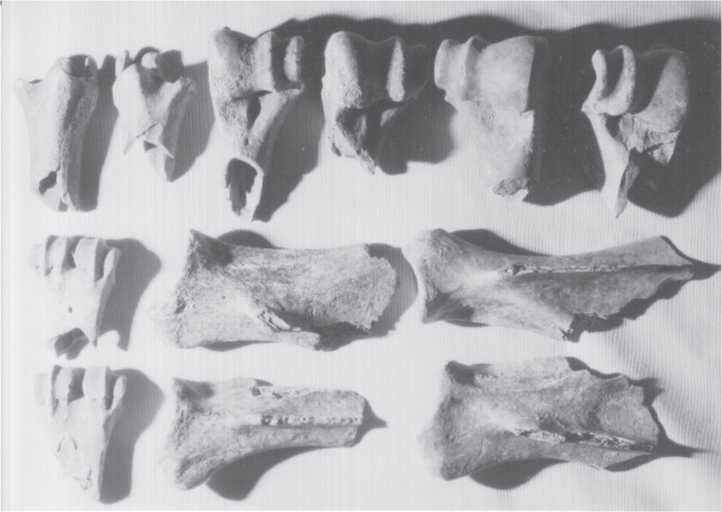

Fig. 3.182 Ust-Kova, bone breakage. Human breakage of reindeer scapulae, tibiae, and metapodial shafts. Lower left metapodial is 5.9 cm long (CGT neg. IAE 8-5-99:30).

15 Tooth dints. As with tooth scratching, there are a few (5.2%) ofthe 116 pieces that exhibit tooth dints (Table A1.15, site 26). The number of dints varies from three to eight. In addition to the astragalus mentioned above, dints occur on a distal tibia fragment, a mandible, and three metatarsals, all reindeer.

16 Pseudo-cuts. Two (1.7%) pieces show pseudo-cuts (Table A1.16, site 26). One of these, a metatarsal, also has tooth dints; the other, a distal humerus fragment, has tooth scratches. Taken altogether (end-hollowing, notching, tooth scratches, tooth dints, and pseudo-cuts), there is clearly identifiable carnivore damage in the Ust-Kova assemblage, although the amount is low, and the type of carnivore would appear to be relatively small, certainly not hyenas, bears, or large wolves. Such a small amount of Pleistocene carnivore damage has several possible explanations. One is that the assemblage was rapidly buried and only a brief amount of time was available for scavenger activity. Second, large scavengers such as hyenas were not present as far north as Ust-Kova, or were not present during the season(s) when this largely reindeer and horse assemblage was slaughtered. However, bears and wolves must have been in the neighborhood, so rapid burial, perhaps initially under a heavy winter snowfall, could have “hidden” the remains long enough to make their decomposition sufficient to make them no longer useful as a source of nutrients. This might especially be the case if living game animals were abundant in the region. Third, the remains that we observed were not representative of the original excavated assemblage due to post-excavation discard. Finally, the game (live and dead) in the area, with a low number of human competitors, may have been so abundant that carnivores had better opportunities to feed elsewhere.

17 Abrasions. Only one fragment (0.9%) has abrasions (Table A1.17, site 26). The scratch lengths of its seven closely grouped striations are about 3.0 cm. They occur on the interior aspect of the anterior border of an adult reindeer proximal scapula fragment. The border is indented and scored as if it had been chewed, but there is no corresponding damage to the external aspect, as would be expected if the specimen had been chewed by a carnivore. Hence, we infer that the abrasions are human-caused. Considering that almost 90% of the Ust-Kova sample have perimortem breakage, the low amount of abrasion stigmata suggests that the tools and anvils used to break up the skeletal elements were made of smooth-surfaced materials such as bone, antler, or wood - not grainy stone.

18 Polishing. There is considerable (34.5%) polishing in the Ust-Kova assemblage (Table A1.18, site 26). Given the relative “wholeness” of the assemblage it is not unexpected that polishing occurs mainly on the ends of fragments because polishing is assessed almost solely on perimortem fractures. Therefore, we feel that the percentage of end-polishing is higher than it might be if breakage had been more extensive. Only one of the five pieces with both end and middle polishing has another indicator of carnivore damage - a specimen with eight tooth dints. This piece is a 15.8 cm long adult reindeer mandible fragment with no anatomical ends. Elsewhere, White (1992) first, and subsequently agreed upon by Turner and Turner (1999), linked fragment end-polishing with abrasive action caused by stirring bone fragments and marrow broth in a ceramic vessel with a rough interior surface. But, being a pre-ceramic Upper Paleolithic site, the Ust-Kova end-polishing must be due to some other mechanism. Trampling, soil acidity, crystal matrix decomposition, and other physical and chemical activity over thousands of years are possible considerations in need of experimental simulation.

19 Embedded fragments. As Table A1.19 (site 26) shows, 11 of the 116 Ust-Kova pieces have one to four embedded fragments. Pieces with embedded fragments have no associated tooth dints or scratches. Only one piece with embedded fragments has an associated notch, which was caused by an impact blow that caused both the notch and the adjacent embedded fragments. Hence, embedded fragments at Ust-Kova appear mainly to be the result of human rather than carnivore activity, and the tool(s) used were smoothsurfaced, like bone, antler or wood.

20 Tooth wear. We did not record observations for the Ust-Kova teeth, since they had no perimortem damage.

21 Acid erosion. There were no examples of stomach acid erosion in the Ust-Kova assemblage. This is consistent with the low amount of severe carnivore damage that would be expected if hyenas had been present.

22 Rodent gnawing. One of the 116 pieces (0.9%) has rodent gnawing marks (Table A1.22, site 26). This is a well-preserved (ivory-condition) 8.7 cm long adult reindeer metatarsal with one anatomical end from Layer 4 (1988). The rarity of rodent gnawing in all of the assemblages reported herein suggests that this form of damage has very

Little taphonomic significance for our sampled area of Siberia. Whatever ecological or taphonomic significance this has is beyond our abilities to explain. The primary inference is that bone remained on the ground surface long enough to receive rodent attention, and was on the ground when these creatures are active. Because the Ust-Kova assemblage has relatively poor preservation, much of it likely was on the ground surface for a long time.

23-24 Insect damage and human bone.

Assemblage.

These variables are not present in the Ust-Kova

25 Cut marks. A total of 17 Ust-Kova pieces (14.7%) exhibit 1-7 cut marks (Table A1.25, site 26). The cuts occur on three scapulae, one astragalus, three humeri, one calcaneus, one radius, two tibiae, and six butchered metapodials. There is no obvious pattern. They range in number from one to seven cuts per piece, with one cut per piece being the most common number. Only one of the cut pieces also has carnivore damage, in this case tooth scratches. It is a poorly preserved (chalky) 10.5 cm long adult reindeer scapula fragment with an intact proximal end. In this assemblage there are no pieces with both cut marks and pseudo-cut marks.

26 Chop marks. There are six pieces with chop marks, which vary fTom one to six chops each (Table A1.26, site 26). The chopped bones include the tibia, humerus, radius, and metapodial. The specimen with six chop marks is a poorly preserved (chalky) 8.7 cm long adult horse tibia with its distal end intact. The chopping is around the joint surface, suggesting that the hoof and nearly meatless metatarsal had been removed.

World History

World History