Hundreds of sites from the Middle Neolithic period, defined here as c. 5500-2500 BC, are known from most areas of China, signaling population increase and occupation of a greater range of environmental zones. Excavations have shed light on farming villages illustrating diverse cultural traditions with respect to housing styles, crafts, and rituals in both residential and mortuary contexts. There were dramatic social changes. One change was the development of social inequality, such that a minority of individuals had privileged social position or status (see Social Inequality, Development of). At the same time, there is evidence for the continued importance of group rituals. In some regions, individual social position was not expressed to the same degree as in other

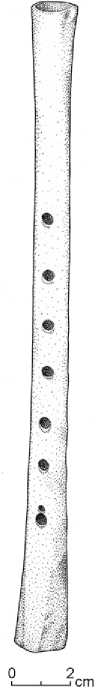

Figure 2 Bone flute from Jiahu. Adapted from Henan Province Cultural Research Institute (1989) Henan Wuyang Jiahu Xinshiqi shidai yizhi di er zhi liu ci fajue jianbao (Short report of the 2nd to 6th excavations at the Neolithic site of Jiahu in Wuyang, Henan). Kaogu 1: 12, figure 28.

Regions. Another change was that regional polities began to develop, indicated by the emergence of regional centers (see Political Complexity, Rise of).

Northern China

Three areas in northern China illustrate these changes well: northeast China, the central Yellow River valley, and the lower Yellow River valley. There is direct evidence for millet farming at Xinle culture sites in Liaoning province c. 5500-4800 BC in addition to pig domestication (Figure 3). Other cultures developed after the Xinle culture in northeast China, but the Hongshan culture is the most intriguing. The remains from the Late Hongshan culture, c. 35003000 BC, provide large-scale evidence for public ritual and skilled craft production, most likely involving specialists. At present, few settlement areas have been identified, so little is known about daily life.

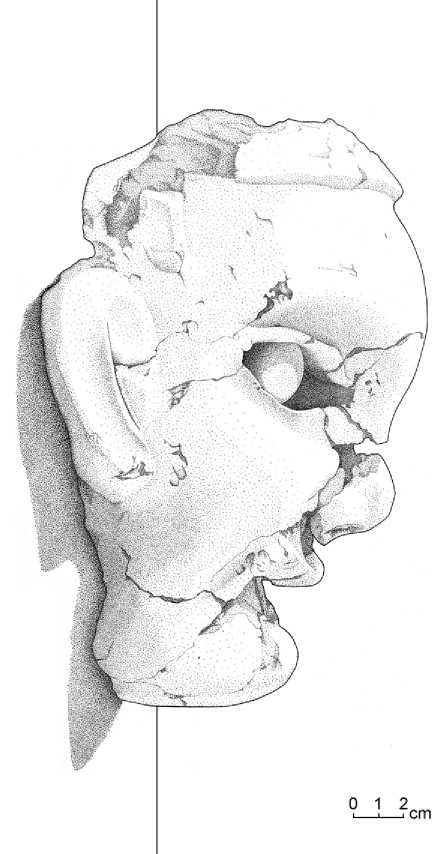

At the huge ritual complex of Niuheliang (roughly 8 X 10 km2), there are numerous stone platforms

Interpreted as altars and stone foundations of structures interpreted as temples. Apparently some walls were plastered and painted as well. Excavators were amazed to find a large clay head depicting an adult female with inlaid jade eyes. They hypothesize this head was originally mounted on a wall (Figure 4). Parts of large animals in clay also were found. In addition, workers found large quantities of unusual, painted pottery cylinders. At another Hongshan site called Dongshanzui, there were smaller clay figurines of obviously pregnant women. A distinctive feature of both sites is several forms of jade animals, both real and mythical (some dragon-like), and a few depicting humans. The ritual areas include rich graves for individual adults - many of which seem to be male - with finely made jade items. There are many debates about the significance of these sites. Some scholars argue that rituals were centered around females, thus indicating relatively high social standing of women at the time. Others emphasize the special burials containing jades as evidence for hereditary social inequality and for a complex society. Public rituals involving people from more than one community in the region would have been an important means for social integration.

Most archaeological research in northern China has focused on the central Yellow River valley. The first Neolithic culture to be investigated was the Yangshao. Now it is realized that the Yangshao culture persisted over 2000 years and encompasses considerable regional variation. Early (c. 5100-3700 BC), Middle (c. 3700-3500 BC), and Late Yangshao (c. 3500-2800 BC) sites are located over an extensive area, especially Shaanxi and Henan Provinces. During the Early Yangshao period, the basic pattern of agricultural villages based on millet and animal husbandry became established. Subsistence practices included hunting and gathering, given the remains of animal bone, fish bone, and wild plants. Early Yangshao villages such as Banpo were quite extensive, with evidence for many circular house foundations, a wide variety of ceramic vessels (fine painted wares and plain wares), and spindle whorls, probably for preparing cloth from hemp.

Yangshao sites have provided considerable information about social organization and ideology from both residential areas and burials. At early settlements like Jiangzhai, clusters of houses faced a central plaza area within a circular, protective ditch. Scholars speculate that these clusters represent social groups such as lineages. At these sites, residential areas were separated from burial areas and kilns. During the later Neolithic period, there were increasingly more villages surrounded by ditches. It is likely that protection of resources was an increasing concern.

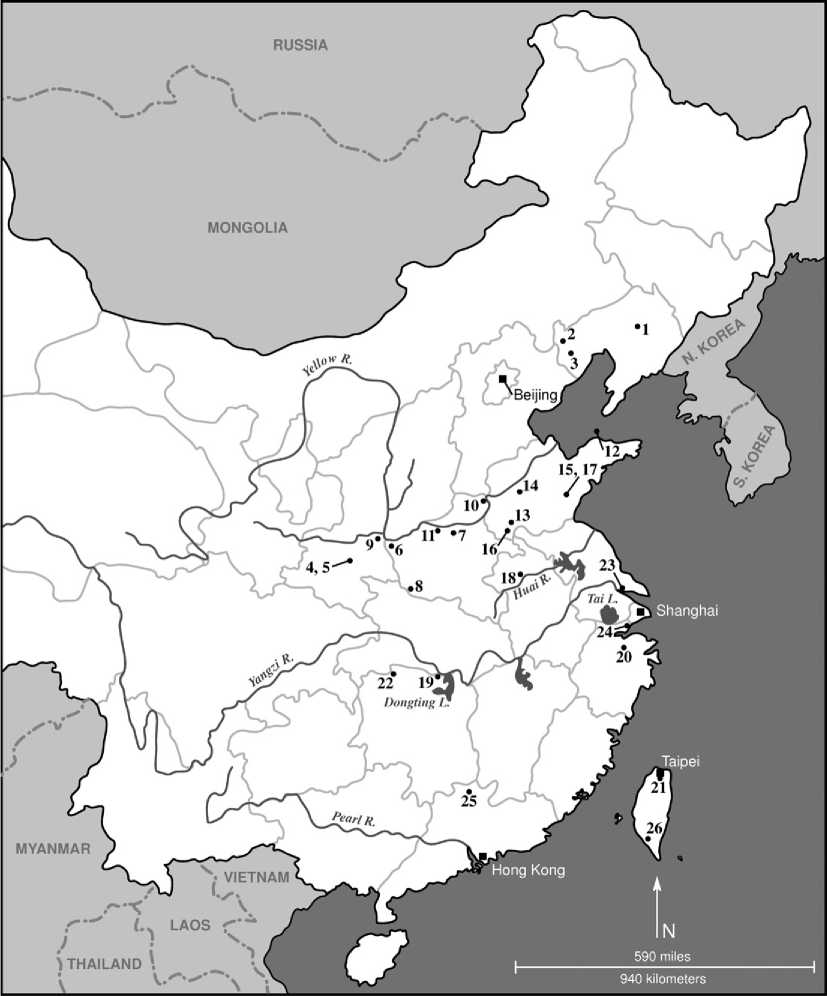

Figure 3 Middle Neolithic sites in China. 1, Xinle; 2, Niuheliang; 3, Dongshanzui; 4, Banpo; 5, Jiangzhai; 6, Xipo; 7, Dahecun; 8, Baligang; 9, Yuanjunmiao; 10, Xishuipo; 11, Xishan; 12, Beizhuang; 13, Wangyin; 14, Dawenkou; 15, Lingyanghe; 16, Jianxin; 17, Dazhujia; 18, Yuchisi; 19, Bashidang; 20, Hemudu; 21, Dapenkeng; 22, Chengtoushan; 23, Yaoshan, Mojiaoshan, Fanshan, Fuquanshan; 24, Zhuangqiaofen; 25, Shixia; 26, Fengbitou.

At more than one site such as Jiangzhai, there are a few unusually large structures. Given their central location, they probably were used by the community as a whole. Two have been discovered in middle Yangshao deposits at Xipo. The one excavated structure there is exceptionally large, over 200 m2, with traces of a red pigment on the flooring. The hearth inside is located close to the entranceway. This too may have served as a locus for communal rituals.

Some houses from relatively late contexts at Dahecun in central Henan have more than room. Yet another house form was discovered at two other Yangshao sites. Excavators found row houses, some with more than one room, in Early Yangshao contexts at the Dahecun site in north-central Henan. This same house form was also found in later Yangshao contexts at the Baligang site in southwestern Henan. There, archaeologists discovered row houses of roughly

Figure 4 Clay head from Niuheliang, hypothesized original mounted appearance. Adapted from Liaoning Provincial Institute of Archaeology and Cultural Relics and Cultural Bureau of Chaoyang City (2004) Niuheliang yizhi. Niuheliang Site, p. 18, figure 15. Beijing: Academy Press.

Equal size with separate rooms, each containing tools of stone and bone as well as pottery vessels. This style of structure seems to emphasize group status rather than individual social status.

Early Yangshao sites contain more than one form of burial, generating much debate. One debate concerns the meaning of a few individual graves of young girls at Yuanjunmiao. These graves contain relatively large quantities of stone ornaments and pottery vessels. Rather than symbolizing wealth, such graves may symbolize some aspect of gender instead. Multiple burials of adults are more common at early Yangshao sites. These may have been opened up as needed to bury people from the same kin group. More Burials for individuals are found in later Yangshao sites such as Dahecun in central Henan. A desire to mark individual social position is more clearly evident for the later phases, when greater variation in grave goods, especially ceramics (some painted), is evident.

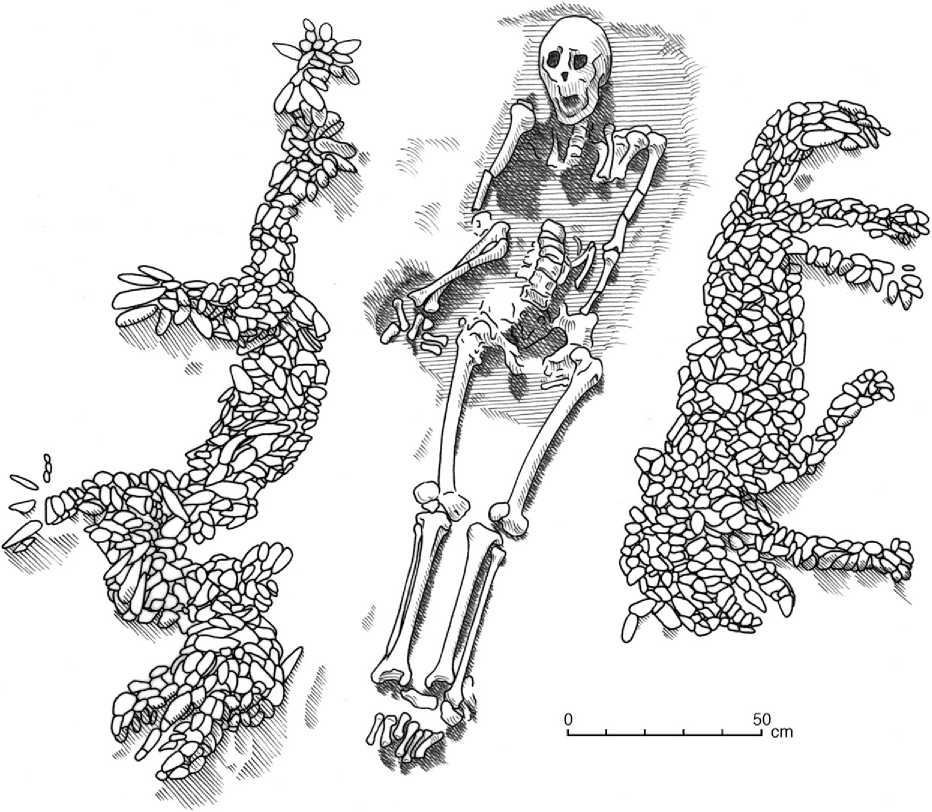

A very unusual Middle Yangshao phase burial was found at the site of Xishuipo in northeastern Henan. Situated around the grave of an adult male were skeletons of three youths (both males and females) that have been interpreted as sacrifices. On either side of the adult were life-sized images made from shells that seem to represent a tiger and a dragon (Figure 5). It has been suggested that the animals represent features of constellations. It is likely that the deceased was a ritual specialist whom the ancient people believed could communicate with the heavens. Furthermore, this ritual specialist was highly regarded and was a kind of village leader.

Only a few sites in the central Yellow River valley from the middle and Late Yangshao periods have material evidence for increase in social inequality. In comparison with other areas, differences in the quantity and quality of grave goods among graves are not dramatic. Numerous fine, painted pottery vessels are known from residential areas. It appears that a wide range of households had access to these vessels. The site of Xishan in central Henan, however, represents a new form of settlement. This Late Yangshao settlement was surrounded by a wall of rammed earth - a form of settlement that became more common during the final Neolithic period in northern China. Here archaeologists excavated over 200 houses and a central plaza, along with two burial areas. The surrounding wall would have served to protect the inhabitants and their resources from raiding. A number of fine, painted vessels were found. During the later Yangshao period as well, some settlements that were much larger than others nearby, signaling the emergence of settlement hierarchies. Although the functions of the regional centers remain to be investigated, they indicate the emergence of inequality at the community level and the emergence of regional polities.

There were similar changes in the lower Yellow River valley. Millet farming and domesticated animals formed the basis of the subsistence economy in Beixin culture communities, c. 5300-4100 BC, in several areas of Shandong Province. There were primarily individual graves, exhibiting little differentiation. During the subsequent Dawenkou period, c. 4100-2600 BC, there were significant changes in both settlements and burials that reveal variation in social organization. A much larger area was occupied, and boat travel was known, given the extensive settlement found at Beizhuang on an island off

Figure 5 Xishuipo burial. Adapted from Puyang City Cultural Management Bureau, Puyang City Museum, Puyang City Cultural Relics Work Team (1988) Henan Puyang Xishuipo yizhi fajue jianbao (Short report on excavations at the Xishuipo site in Puyang, Henan). Wenwu 3: 4, figure 5, and Yang XN (2004) New Perspectives on China's Past. Chinese Archaeology in the Twentieth Century, Vols. 1 and 2, p. 23, figure 19. New Haven and Kansas City: Yale University and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

The Shandong coast. Surveys in Shandong reveal evidence for the emergence of settlement hierarchies. The most telling evidence for social differentiation, though, is found in the striking burials. In contrast to burials from the central Yellow River valley, they reveal increasing efforts to display individual social status.

There is little differentiation among Early Dawenkou period (c. 4100-3500 BC) burials in Shandong, as seen from the site of Wangyin. There were both multiple and individual burials at this site. The single graves exhibited minor differences in the nature of grave goods on the basis of age and sex, rather than individual status defined by wealth or power. During the Middle Dawenkou period (c. 3500-3000 BC), more differences in mortuary treatment for individuals emerged. At more than one site, a few graves, for both females and males, contain greater quantities of finely made objects than others.

For the Late Dawenkou period (c. 3000-2600 BC), differences among graves are dramatic. The Dawenkou site is the most famous, with a minority of burials containing finely made pottery vessels, symbolic jade tools (no sign of use), ornamental objects of elephant ivory, and pieces of alligator hide that probably were used to fashion drums. The rare materials would have been acquired through exchange networks. Many of these goods probably were made by craft specialists, and some were made just for burial. In addition, some grave pits were more elaborate than others, with special earthen ledges to hold artifacts, and with wooden coffins. A common feature of most cemeteries is a tremendous quantity of pottery as grave offerings. At the Dawenkou site, one grave for an adult female contains 90 vessels, and one grave at Lingyanghe in eastern Shandong contains 160 pots. Different functional types are included, for cooking, storage, serving, and drinking. Drinking cups in rich burials are common, although there are interesting differences among contemporary cemeteries. At Jianxin, some rich graves contain large quantities of small jars called ‘ping’ instead. Some scholars argue that particular vessels in Late Dawenkou graves were the result of funeral feasts, while others were intended for use by the deceased in the afterlife. A funeral feast seems particularly likely for one grave at Dazhujia in eastern Shandong. This grave contains a large ‘zun’ jar on the ledge, and several finely made, stemmed cups, carefully laid out on the chest of the deceased. Remains of pigs, notably the skulls, are other common features of Late Dawenkou period graves.

For other areas, however, symbolizing social position with material goods may not have been a priority. At the Late Dawenkou site of Yuchisi in northern Anhui, archaeologists found row houses similar to those from Dahecun and Baligang. Some contained over 40 rooms, including many objects used for daily life (pots, tools). As at Baligang, there was excellent preservation of the clay house walls, since they were burnt. It appears that the burning was a deliberate construction technique to harden the walls. Another intriguing finding was the large jars called ‘zun’ with incised symbols (some covered in red pigment). Some of these symbols (including the sun and moon) are very similar to those found at late Dawenkou period sites in Ju county, Shandong, to the northeast. Unlike those found in Shandong, however, a few of these vessels served as burial jars for children. The row houses seem to emphasize group membership, as elsewhere, although differences in wealth may have begun to emerge, judging from the fine ceramics (some with red pigment) and jade ornaments found in a few graves. Protection of the whole community was a concern, since a moat was discovered around the entire settlement. Excavations at Yuchisi, located in the southern extent of the Dawenkou culture area, revealed a diet based on rice as well as millet. As noted for Jiahu, the historic dividing line between rice-growing areas and those for millet does not always characterize the Neolithic period. Initial studies show that the environment during parts of the Neolithic period was warmer and moister than at present.

Southern China

There is abundant evidence for fully sedentary communities that relied on rice farming in more than one area of southern China during the middle Neolithic period, c. 5500-2500 BC. Large quantities of rice grains have been recovered from sites in the central and lower Yangzi River valleys. Late Pengtoushan culture (c. 5500-5100 BC) deposits at the Bashidang site in the central Yangzi river valley also yielded a surrounding ditch interpreted as a moat and traces of a small earthen wall. This tradition of surrounding residential areas with protective walls increases over time in China, especially in the north. At Zaoshi culture sites in Hubei (c. 5500-4500 BC), bones of water buffalo, an animal commonly used for plowing in southern China, were found. Huge amounts of rice were recovered from the Hemudu site (c. 50004500 BC) in the lower Yangzi river valley, thanks to the waterlogged deposits there. Other aquatic domesticated and wild plants as well as wild animals were also found, providing a fuller picture of the diet at the time. The excellent preservation conditions enabled archaeologists to find a variety of craft goods, too. These included wooden artifacts, a boat oar, fragments of reed mats, bone whistles, and the earliest known lacquer container. Other, well-preserved sites from the Hemudu culture have been discovered recently with equally impressive remains.

Different subsistence practices developed during the Dapenkeng period in coastal areas of Taiwan, c. 5000-2500 BC. Similarities to the cultures of the Pacific islands are evident, from the discovery of artifacts for fishing and grooved stone beaters for making tapa cloth. These peoples probably grew root crops such as taro, but at present there is no physical evidence.

Sites in the central Yangzi River valley provide evidence for important changes in settlement organization and in craft production during the Middle Neolithic period. As in the north, there is evidence for increase in social inequality. The site of Chengtoushan in Hunan demonstrates that a new form of settlement emerged during the Daxi period (c. 4500-3000 B. C.). This site continued to be occupied during part of the subsequent Qujialing (c. 3000-2500 BC) period. Like Xishan in the north, this settlement was surrounded by an earthen wall and moat. The size and remains inside the walled enclosure make it likely the site was a regional center. Some houses were built on rammed earth platforms, a labor-intensive style of housing associated with elites during the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age periods in more than one part of China. The settlement exhibits planning, with a pottery production area in the west and cemeteries to the northwest. The excavators identified a ritual area, where they propose sacrifices were made, anticipating practices known from the historic period in more than one area of China. Other Daxi and Qujialing period sites in the central Yangzi River valley demonstrate significant development of ceramic technology.

A variety of labor-intensive ceramics were produced, such as elegantly shaped, thin-walled, and finely painted vessels. These relatively rare vessels have been found in both residential areas and burials.

At present, little is known about residential areas at later sites in the lower Yangzi River valley. Numerous burials have been found near Shanghai from the Majiabang (c. 4500-3700 BC) and Songze (c. 37003300 BC) periods. Songze period ceramics include finely decorated (painted, incised) jars and serving stands. Mourners also displayed the social position of the deceased by placing jade ornaments in a minority of graves.

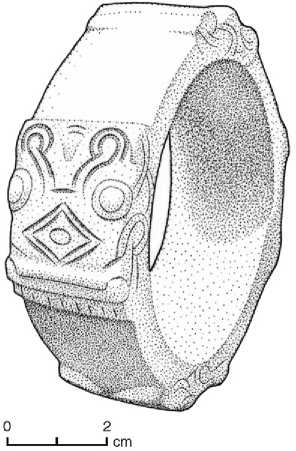

The most elaborate graves discovered in the lower Yangzi River valley, without a doubt, are from the Liangzhu (c. 3300-2200 BC) period. Although these graves contain finely made pottery vessels (elegant shapes, some black and polished), it is the jade objects that have received the most attention. There is an amazing variety of finely made jade ornaments, with respect to size, shape, and color. Many have no known function. The intriguing ‘taotie’ (‘animal mask’) design on some jades (Figure 6) also appears on later, historic period bronze vessels in the Yellow River valley to the north. A few rich graves at sites such as Fanshan contain large jades; large size may be another symbol of high social status. Other jade objects include symbolic weapons (no signs of use) that probably once were hafted with wooden handles. These probably served as symbols of power and authority.

Figure 6 Liangzhu jade from Yaoshan. Adapted from Zhejiang Province Institute of Archaeology (2003) Yaoshan, p. 216, plate 13. Beijing: Wenwu Press.

Jade is an extremely labor-intensive rock to work with, requiring extensive grinding and polishing. In addition, many pieces are very finely incised. The quantity and variety of pieces, in addition to the material itself, point to production by specialists. The sheer quantity in some graves (often over 100 pieces) might have necessitated production before an individual died. Little is known about how individuals used these items during their lifetimes. The difficulty of workmanship, the necessity for exchange networks to acquire the raw jade, and the quantities in graves all point to the high social position of the individuals in these graves. Several of the interred skeletons have been identified as males, but there is not always sufficient preservation to identify the sex of the deceased. Typically, a large quantity of jade items is distributed from the head to the foot of the deceased.

The highest concentration of Liangzhu sites is found near the Lake Tai area in Zhejiang. Many cemeteries, such as Yaoshan in Zhejiang, only contain a dozen or so graves, each very rich in terms of interred goods. In addition to large quantities of jade, the burials include fine lacquer items, some inlaid with jade. Items made from elephant ivory have been found in more than one Liangzhu grave as well. Sites such as Yaoshan and Fanshan have been interpreted as elite cemeteries, with the location of graves of commoners unknown. An important exception is the recently excavated site of Zhuangqiaofen in Zhejiang. At present, this is the largest known Liangzhu cemetery, with over 200 burials, representing a wider range of the community.

Yaoshan and other elite cemeteries from the Liangzhu period were first constructed as human-made, earthen platforms several meters high over the floodplain. Many Liangzhu site names end in ‘shan’, meaning ‘mountain’ or ‘hill’. This would have provided a dramatic setting for funeral ceremonies. It is likely that ceremonies continued to take place periodically after burial of the deceased. At Yaoshan and the Fuquanshan site closer to Shanghai, archaeologists found altars made of earth and stone. At Fuquanshan, they also found sediments that they believe resulted from sacrificial offerings with fire. At the Mojiaoshan site in Zhejiang, the large platform construction has an area of over 3 ha, with a height of 10 m. In addition, there were remains of smaller rammed, earthen platforms and a large structure. Some of these platforms were constructed partially by fired adobe bricks, indicating even greater labor expenditure. Large structures also could have been Used for public rituals around the graves of individuals who were important ancestors to the whole group. If additional excavation of the site reveals more of these structures, the structures may have been elite residences. The entire site covers an area of nearly 40 km2. It is likely to be a regional center for the numerous Liangzhu sites in the Lake Tai area.

In southernmost parts of the mainland, Neolithic communities (c. 3500-2500 BC, and later) relying on rice farming and fishing have been identified, particularly in Guangdong and Fujian provinces. The best-known culture is Shixia, located in southern Guangdong. This culture developed c. 3000 BC and is represented primarily by burials. Like Neolithic cultures further north, there was a tradition of producing prestigious goods such as fine ceramics and jade items, in addition to items for daily use. Some of the same forms of pottery and jade items were found in the Shixia burials. Fieldwork at sites in Fujian thus far indicates similarities with cultures to the east in Taiwan. The Dapenkeng culture continued in coastal areas of Taiwan, and other cultures become evident such as Fengbitou in the south. In Hong Kong, a number of rescue projects have taken place during the past decade in advance of construction projects. They also have uncovered rice farming and fishing villages, a cultural pattern that has persisted in southern China for millennia.

World History

World History