While it is extremely difficult to identify a distinct Mesolithic phase across the Northwest Frontier and Kashmir region, pollen analysis from peat deposits in the central Himalayas suggests that the period between c. 4000 and 2500 BC was one of increased temperature and rainfall - a result of enhanced monsoon strength. Associated with the frequent growth and decline of pine forests, these changes coincided with the emergence and spread of Neolithic communities within the valleys and vales of the region. Notably later than the sites of Mehrgarh and Kili Ghul Muhammed to the west (see Asia, South: Baluchistan and the Borderlands), the Neolithic of the Swat Valley, and Vale of Kashmir possesses its own distinct regional character.

Kashmir Valley

One of the most extensively excavated sites is Burzahom, ‘the place of Birch’, in the Vale of Kashmir. Situated 16 km southwest of Srinagar on a saddle above the lakes, it was identified in the 1930s but not extensively excavated until the 1960s. Burzahom’s first phase, IA, is aceramic and dates to between 3000 and 2850 BC. Phase 1B, dating to between 2850 and 2250 BC, is associated with the introduction of coarse, thick-walled, and over-fired ceramics with mat impressions. This phase also witnesses a steady increase in the number of domesticated animal bones and a corresponding decrease in the presence of wild species.

The type site of a corpus of over 40 similar settlements, Burzahom’s Neolithic levels are associated with an assemblage of bone, antler, and polished stone tools, the latter including ring stones, axes, and rectangular sickles. However, the most characteristic feature of the site is the 37 bell-shaped pits dug into the loess. The largest of these was 2.74 m wide at the top and 4.57 m wide at the bottom, with a depth of 3.95 m. Some deeper pits have steps, while others had their floors painted with red ochre and their walls plastered (Figure 7).

Evidence from Gufkral, 25 km southwest of Burzahom, has provided rather fuller evidence for subsistence and suggests that farming, herding, and hunting supported its inhabitants. Certainly, this is likely from the assemblage of wild ibex, bear, sheep, goat, cattle, wolf, and deer alongside with domesticated sheep, goat, wheat, barley, and lentils. The discovery of jade beads from these sites also indicates the movement of materials over long distances.

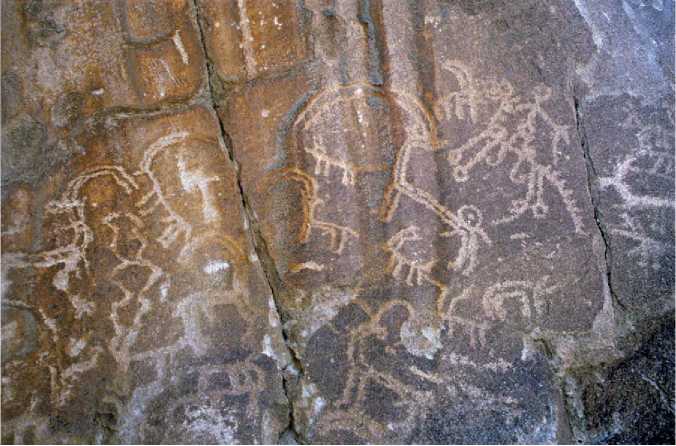

Figure 6 Petroglyphs of Markhor and hunters on the Sacred Rock of Hunza.

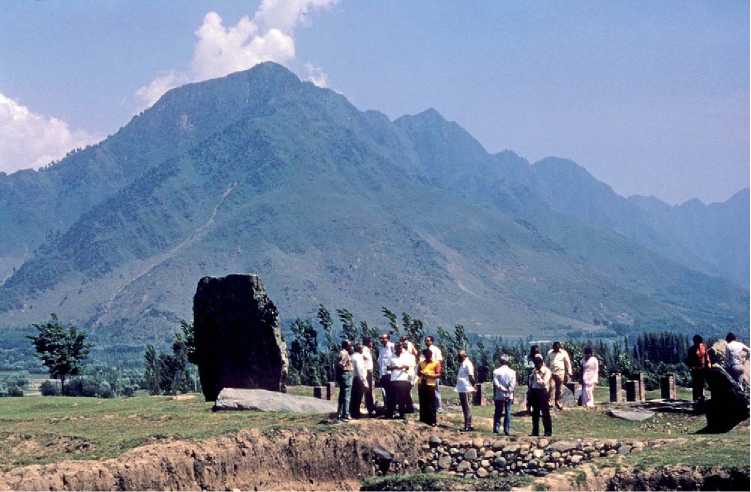

Figure 7 General view of the site of Buzahom.

Swat Valley

Despite the presence of occupation dating to the third millenium BC in the cave of Ghaligai, evidence of food-producing communities in Swat is somewhat later with the majority of sites occupied from c. 1700 BC onward. Remarkably similar to the evidence from Kashmir, the Pakistani-Italian team have provided a greater corpus of knowledge, ranging from the chronology of sites to their location within the landscape and the seasonal mobility of their occupants. Additionally, there are many more radiocarbon dates from Swat than from Kashmir.

Aceramic in its earlier phase, ceramics are introduced in Period II of Ghaligai’s sequence in c. 1810 BC alongside limestone mortars whose presence in these levels is suggestive of food-processing strategies, but most evidence has been recovered from the sites associated with pits, many of which are also bell-shaped and located on saddles above the river Swat. Loebanr III, for example, has nine large pits and numerous smaller pits containing ceramic vessels, bone objects, terracotta figurines and its faunal record includes wild cat, tiger, deer, Himalayan goral, markhor, hare, and porcupine as well as domesticated dog, pig, zebu, goat, and sheep.

Taxila Valley

Not all Neolithic occupation was restricted to the northern valleys and it is possible that alluvial deposition has masked the presence of earlier sites down on the plains. One known site is Sarai Khola, some 3 km southwest of the Early Historic city of Taxila. Its earliest period with ground-stone axes, stone-blade industry, bone points, and burnished pottery with mat-impressions has been characterized as Neolithic and dated to c. 3000 BC. The presence also of a number of pits suggests a link with the early food-producing communities to its north (see Asia, South: Neolithic Cultures).

Dwelling Pits or Granaries?

The pits at Buzahom, Gufkral, Kalako-deray, Loebanr III, Aligrama, and Ghaligai have traditionally been interpreted as underground dwellings occupied during the cold winter months. However, experiments demonstrate that fires would have created a reduced atmosphere, making living conditions untenable. It now seems likely that the pits were used to store grain over the winter when the transhumant inhabitants of the region relocated to the lower valleys or plains. When sealed, the pits’ reduced atmosphere created ideal conditions for storage, protecting grain against microorganisms, humans, mammals, and rodents (Figure 8).

World History

World History