Before reviewing general patterns in the archaeological records of North and South America, a comment on founding populations and demography is useful. Whether small founding populations were engaged in the initial dispersion or colonization (meaning more territorial) in the Americas, they surely had demographic requirements. That is, other people were a crucial resource that probably placed limits on how far away a group could venture from its nearest neighbor. Any small founding group probably needed to maintain networks of potential mates, social interaction, and exchange of information on foods, and other resources. Such social ties would help to explain the general uniformity of technology across vast areas of a continent, such as the similarities in Clovis and later projectile points in North America and in the many different stone tool industries in many parts of South America (Figure 4). One of the most important factors determining the long-term and long-distance movement of founding populations across different landscapes was their ability to adapt their technologies and social organizations to the exploitation of new food sources and yet maintain social ties with neighboring or splinter groups. Any constraints on this movement were likely to be greatest where resources were limited. In homogenous, relatively static environments such as the boreal forests of high latitude zones in North America, the grasslands of the Great Plains in North America, the Pampa and Patagonia grasslands of South America (Figure 5), and the coasts in both continents, where

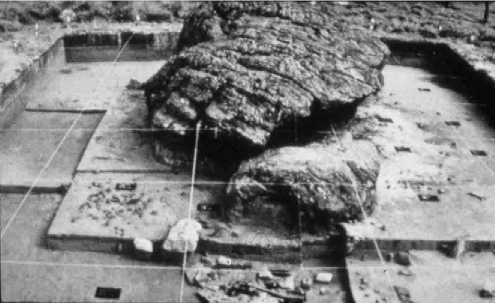

Figure 4 General view of the excavated TibittO site in Colombia showing a large boulder surrounded by stone tools and the bone remains of extinct animals.

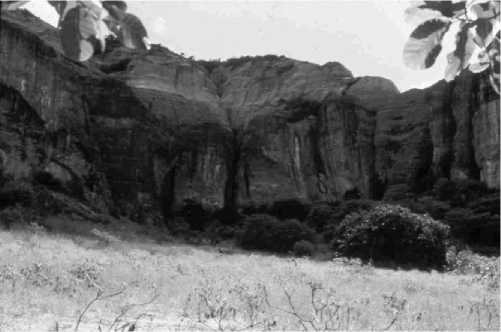

Figure 5 General view of Panualauca Cave in the high grasslands of central Peru where early human artifacts were associated with the bone remains of palaeocamelids.

Resources were patchy and probably less reliable in time and space, groups probably had little choice but to move more often. The temperate deciduous forests of the Eastern United States and parts of the Andes, Brazil, and Venezuela, which were more heterogeneous and generally richer in foods, may have supported more different types of economies, and groups may have stayed longer in some areas. Temperate and tropical forests, in particular, probably gave people many subsistence options and the opportunity to reside longer, but perhaps less incentive to specialize or concentrate on particular resources. Further, because people likely would have spent more time exploring these areas and getting to know the variety of resources available, these longer stays may have sparked more social cohesion and perhaps more complexity. Greater social and economic complexity generally is inferred from the appearance of new kinds of archeological sites, such as burials and rock art, the adoption of new stone technologies, the exploitation and manipulation of new food types, including domesticated plants, and an increase in the exchange of products over long distances.

There is archaeological evidence that by 12 000 to

11 000 years ago people had colonized most broad environments in the Americas, such as deciduous forests, coasts, tropical rain forests, cold steppe and shrub grasslands, and deserts. With the exception of eastern Beringia (Alaska and Yukon territory) in the far northwest, firm evidence for early colonization of the northern boreal forests and tundra of modern Canada is still lacking, although promising evidence comes from the site of Bluefish Caves where modified bones suggest early human habitation before

12 000 years ago. Another series of early sites is found in the Nenana Valley of Alaska that date between 11500 and 11000 years ago and reveal stone tool technologies remotely similar to those in eastern Siberia. Thus, it appears that by at least 11 500 years ago, people with similar tool technologies moved from far eastern Russia to Beringia and thus became some of the first people to have entered the New World. It is not known whether these people migrated farther south through ice-free corridors or followed the Pacific coastline. Further, the stone tool industries from these areas appear to have little resemblance to Clovis stone tools. By 11 200 years ago, there is widespread evidence of the Clovis culture throughout the middle sections of North America and in parts of northern Mexico. Clovis and other point traditions are widely distributed in the eastern United States and Canada at the Vail, Bull Brook, Shoop, Shawnee-Minisink, Debert, and other sites. In west-central North America, along the eastern slopes of the Rockies and on the southern plains, Clovis sites are common. Studies in the Plains and Southwest deserts reveal parallel or sequential point traditions associated with hunting economies, especially big-game (mammoth, giant ground sloth) in open terrain. These also include Clovis followed by several regional point styles such as Folsom, Midland, Goshen, and Plainview. Some of the earliest Clovis sites are found in the least expected places, for instance, the southeastern United States where several localities (Little Salt Springs, Thunderbird, Topper) date earlier than those in the west and southwest United States. In addition, Clovis is much less frequent in the far western United States where nonfluted points are more prevalent and associated with varying hunting and gathering economies.

Although generally perceived as a big-game hunting tradition, not all Clovis and other early sites support this notion. Better preserved than plants, faunal remains suggest that any idea of a single Late

Pleistocene economy is unrealistic. For instance, at Meadowcroft Shelter and other early woodland sites in eastern North America, both Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene (c. 11 500-8000 years ago) faunas are dominated by small and medium-sized animals, perhaps reflecting greater environmental stability in the eastern woodlands and earlier extinction of large mammals. If so, then human populations may also have been better able to maintain themselves in the woodland habitats of the Eastern United States than elsewhere. In fact, some archaeologists have proposed that rather than being specialized big-game hunters, Clovis and later point-makers were broad-spectrum hunters and gatherers, particularly in the eastern woodlands and southern areas where the environment was more diversified than northern latitudes.

In contrast to North America, the fluted point tradition played a minor and late role in the peopling of South America. Instead, a wide variety of fluted and nonfluted point industries associated with broad-spectrum economies are found in many regions from at least 12 500 to 11 000 years ago. In the Andes and in the eastern tropical lowlands and southern grasslands, many caves and rockshelters were occupied intermittently from at least 11 800 to 11 000 years ago, especially in eastern and central Brazil and in extreme southern Patagonia. It is not known whether this pulsing of rockshelter occupations is simply an artifact of climatic change or simply human patterns of social and economic change. Strong similarities in the dates of occupation pulses as far apart as 1000 km, however, implicate climatic changes operating on subcontinental scales. The surviving evidence of recently discovered human occupation of the central Amazon basin and other forested areas where archaeological exploration and visibility are minimal may be no more than a small sample of the populations that once concentrated there and elsewhere.

In summarizing the evidence from South America, it is clear that early technological and economic developments show cultural diversity at the outset of human entry and the establishment of ever increasingly distinct regional economic combinations along the coasts and in highland Andean valleys. Although the current archaeological evidence is still too scanty to discern the specifics of these developments in all environments, two general transitions can be inferred. The first was a change in adaptive strategies and organizational abilities during and at the end of the Pleistocene period. This transition signifies the rapidly increasing ability of people to recognize the environmental potentials that existed in coastal wetlands, desert oases, intermontane valleys, lowland river valleys, and high altitude grasslands, to communicate these potentials to others and to take advantage of them, and to develop the social organization required to exploit resources in a wider variety of compressed environments. Second, early people probably learned many hunting and gathering techniques, and on occasion employed them to domesticate some plants (i. e., squash, beans, chili peppers, and chenopodium) and to begin a semisedentary or subterritorial lifestyle in some areas by at least 10 000 to 9000 years ago. With the exception of only two sites in South America - Taima-Taima in Venezuela and Tagua-Tagua in Chile - there is no hard evidence to show that big-game hunting was the mainstay of the earliest known South Americans. Instead, most early South Americans employed a broad-spectrum economy that was associated with many different tool technologies and reduced territorialism.

Another dimension of Late Pleistocene subsistence throughout the Americas remains difficult to investigate though the evidence of older sites suggests that marine foods also were exploited. Changes in sea-level and occupation hiatuses at several coastal sites in Peru (Quebrada Tacahuay, Quebrada Jaguay, Quebrada de los Burros) and Chile (Huentelafquen, Quebrada de Las Conchas) during the 11 000-10 000-year period mean that earlier marine-oriented sites may exist on submerged continental shelves. Freshwater and brackish fish also were taken in northern Peruvian Paijan sites dated around 10 500 years ago and several early sites along rivers in eastern Brazil (Figure 6). Similar evidence is being retrieved from a few sites along the submerged shelves of Florida and Washington states.

These patterns eventually may help to explain the rise of later more socially and economically complex societies in some areas of Mexico and South America where we know that large nomadic hunter-gatherer bands eventually settled down to establish productive food economies and dynamic social systems by at least 9000 years ago. Not known are the conditioning factors that brought about these changes in regional environmental settings. The archaeological evidence for these changes is weak in most areas. Only in the past 20 years have we come to realize how widespread broad-spectrum economies were in the Late Pleistocene of the eastern woodlands of the United States and especially along the Pacific coast, lowland tropical forests, and northern Andean regions of South America. This is probably a result of increased archaeological research and better archaeological recovery techniques (i. e., ground penetrating radar to find buried sites, extraction of plant remains from archaeological sediments) to find new foods which have opened the minds of archaeologists to the idea that not all early people were big-game hunters but exploited a wide variety of food types in many different

Figure 6 General view of the Pedra Furada site in eastern Brazil where Late Pleistocene human artifacts were excavated.

Figure 7 General view of the Monte Verde site where an early human campsite was excavated in southern Chile.

Figure 8 View of the remains of a wishbone-shaped hut structure excavated at Monte Verde.

Environments. Examples of different foods are the thousands of snails recovered from Late Pleistocene Paijan sites on the north coast of Peru; the variety of seeds, nuts, soft leafy plants, tubers, and seaweeds

Recovered from floors of residential huts at Monte Verde (Figures 7 and 8); and the abundant remains of palm nuts and other plant types found at several caves and rockshelters in eastern Brazil. Despite these kinds of foods, other groups developed economic practices that often relied on a specific species, for instance, hunting high quantities of bison on the Great Plains of North America and camelids (guanaco) or a few other species on the high puna or tundra of the Andes.

If many Late Pleistocene populations were not as big-game focused as earlier interpretations suggested, the impression of long-distance movement over the landscape is suggested in many areas of the Americas by the infrequency of sites, which are often many kilometers apart. The absence or infrequency of sites, of course, also may represent a sampling bias, with the surviving sample of sites located and studied by archaeologists today probably representing no more than a fraction of the original settlements. As noted earlier, the constant destruction of sites by modern construction or by erosion and other natural forces make it difficult to find sites in many places.

The strongest evidence for the movement of early people across the landscape and the exchange of goods between them primarily comes from Clovis and Folsom sites on the Great Plains of North America, where some of the raw material used to make projectile points and other stone tools often traveled hundreds of kilometers to reach a site. The presence of exotic stone material in sites offers some support for great human mobility, or the alternative possibility that people developed geographically more extensive exchange and alliance networks as a means of coping with more unproductive environments where quality resources were scare or unavailable. Long-ranging contacts between Late Pleistocene populations also may be indicated by the general uniformity of the Clovis and other early point technologies across North America and to a lesser extent across South America. The scale and intensity with which similar point types moved across the Americas decreased significantly after 10 000 years ago, when people became less mobile and more territorially settled into regional environments.

World History

World History