Biologists classify humans within the primate order, a subgroup of the class Mammalia. The other primates include lemurs, lorises, tarsiers, monkeys, and apes. Humans—together with chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, orangutans, gibbons, and siamangs—form the hom-inoids, colloquially known as apes, a superfamily within the primate order. Biologically speaking, as hominoids, humans are apes.

The primates are only one of several different kinds of mammals, such as rodents, carnivores, and ungulates (hoofed mammals). Primates, like other mammals, are intelligent animals, having more in the way of brains than reptiles or other kinds of vertebrates. This increased brain power, along with the mammalian pattern of growth and development, forms the biological basis of the flexible behavior patterns typical of mammals. In most species, the young are born live, the egg being retained within the womb of the female until the embryo achieves an advanced state of growth.

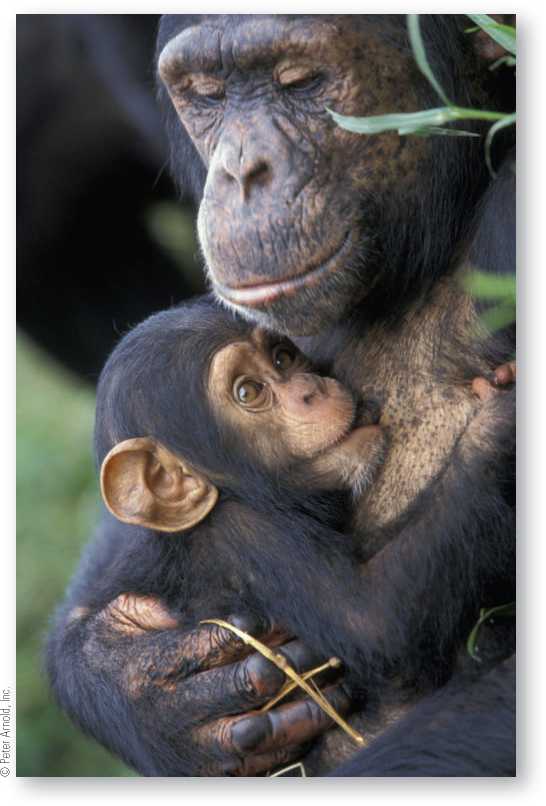

Once born, the young receive milk from their mother’s mammary glands, the physical feature from which the class Mammalia gets its name. During this period of infant dependency, young mammals learn many of the things they will need for survival as adults. Primates in general, and apes in particular, have a very long period of infant and childhood dependency in which the young learn the ways of their social group. Thus, mammalian primate biology is central to primate behavioral patterns.

Relative to other members of the animal kingdom, mammals are highly active. This activity is made possible by a relatively constant body temperature, an efficient respiratory system featuring a separation between the nasal and mouth cavities (allowing them to breathe while they eat), a diaphragm to assist in drawing in and letting out breath, and a four-chambered heart that prevents mixing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood.

Mammals possess a skeleton in which the limbs are positioned beneath the body, rather than out at the sides. This arrangement allows for direct support of the body and easy flexible movement. The bones of the limbs have joints constructed to permit growth in the young while simultaneously providing strong, hard joint surfaces that will stand up to the stresses of sustained activity. Mammals stop growing when they reach adulthood, while reptiles continue to grow throughout their lives.

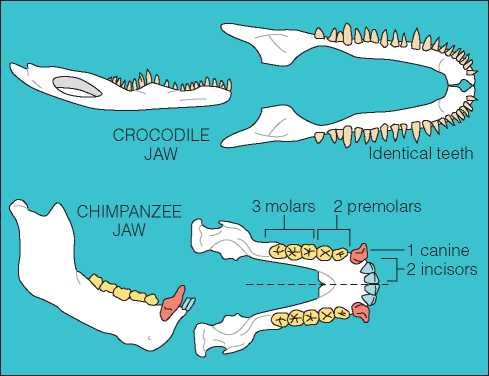

Mammals and reptiles also differ in terms of their teeth. Reptiles possess identical, pointed, peglike teeth while mammals have teeth specialized for particular purposes: incisors for nipping, gnawing, and cutting; canines for ripping, tearing, killing, and fighting; premolars that may either slice and tear or crush and grind (depending on the kind of animal); and molars for crushing and grinding (Figure 3.2). This enables mammals to eat a wide variety of food—an advantage to them, since they require more food than reptiles to sustain their high activity level. But they pay a price: Reptiles have unlimited tooth replacement throughout their lives, whereas mammals are limited to two sets. The first set serves the immature animal and is

Nursing their young is an important part of the general mammalian tendency to invest high amounts of energy into rearing relatively few young at a time. The reptile pattern is to lay many eggs, with the young fending for themselves. Interestingly, ape mothers, such as this one, tend to nurse their young for four or five years. The practice of bottle-feeding infants in the United States and Europe is a massive departure from the ape pattern. Although the health benefits for mothers (such as lowered breast cancer rates) and children (strengthened immune systems) are clearly documented, cultural norms have presented obstacles to breastfeeding. Across the globe, however, women nurse their children on average for about three years.

Figure 3.2 The crocodile jaw, like the jaw of all reptiles, contains a series of identical teeth. If a tooth breaks or falls out, a new tooth will emerge in its place. Mammals, by contrast, possess precise numbers of specialized teeth, each with a particular shape characteristic of the group, as indicated on the chimpanzee jaw: Incisors in front are shown in blue, canines behind in red, followed by two premolars and three molars in yellow (the last being the wisdom teeth in humans).

The ancestral primates possessed biological characteristics that allowed them to adapt to life in the forests. Their relatively small size enabled them to use tree branches not accessible to larger competitors and predators. Arboreal life opened up an abundant new food supply. The primates were able to gather leaves, flowers, fruits, insects, bird eggs, and even nesting birds, rather than having to wait for them to fall to the ground. Natural selection favored those who judged depth correctly and gripped the branches tightly. Those individuals who survived life in the trees passed on their genes to the succeeding generations.

Although the earliest primates were nocturnal, today most primate species are diurnal (active in the day). The transition to diurnal life in the trees involved important biological adjustments that helped shape the biology and behavior of humans today.

Replaced by the permanent or adult teeth. The specializations of mammalian teeth allow species and evolutionary relationships to be identified through dental comparisons.

Evidence from ancient skeletons indicates the first mammals appeared over 200 million years ago as small nocturnal (active at night) creatures. The earliest primatelike creatures came into being about 65 million years ago when a new mild climate favored the spread of dense tropical and subtropical forests over much of the earth. The change in climate and habitat, combined with the sudden extinction of dinosaurs, favored mammal diversification, including the evolutionary development of arboreal (treeliving) mammals from which primates evolved.

World History

World History