Okladnikov Cave is located in the northern foothills of the Altai Mountains at approximately 650 m above sea level. The south-facing limestone cave is about 14 m above a side valley meadow floor of the Sibiryachikha River (Fig. 3.89), a tributary of the Anui River. The cave is about 1km from a small village named Sibiryachika (Fig. 3.90). Kuzmin and Orlova (1998:6) place the cave at 51°40' N, 84°20' E. The Russia-China border is relatively close, only some 60 km due south. Originally named after the just-mentioned nearby village, the site was renamed by Academician Anatoly P. Derevianko in honor of his predecessor, the first director of the now-named Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography in Academgorodok, who also possessed the title Academician. That some structure or archaeological monument should be named after Okladnikov goes without saying, given his distinguished career. This career has been masterfully described by A. K. Konopatsky (2001, 2009), and in less detail but equal respect by R. S. Vasilievsky (1999), although as will be seen in the following text, perhaps this particular cave is not the most appropriate one to bear his name.

The cave was first examined in 1984 by Derevianko and Yaroslav I. Molodin. Test excavation began the same year and continued until 1987, first under the field supervision of V. T. Petrin, who worked mainly in the entrance area, followed by Serghei V. Markin, who carried out the interior investigation. The two-branched, tube-shaped cave has a caplike overhang entrance ledge that protects the nearly level entrance stone bench that is 8 m wide, 2 m high, and 4.2 m deep. The narrow, low, pitch-black tunnels extend into the hill for about 35 m. Compared with the grotto entry, the rest of the cave looks like a cold, wet burrow. Additional information is readily available in English (Derev’anko et al. 1998). On the basis of our personal experience in the cave, we regard these tunnels as uninhabitable, and whatever cultural remains found in them resulted from animal bioturbation of the outside living area.

One hundred meters away and slightly higher on the hill is Sibiryachikha VI, an animal cave in which a child’s humerus was found by Ovodov in 1985. He found it with Pleistocene faunal remains during his test excavation of this small cave. In Ovodov’s view this cave would have served better for human use than Okladnikov Cave, but he encountered no evidence of human occupation. In August 2006 we examined this subadult humerus shaft, which shows evidence of small carnivore or vole chewing. A small

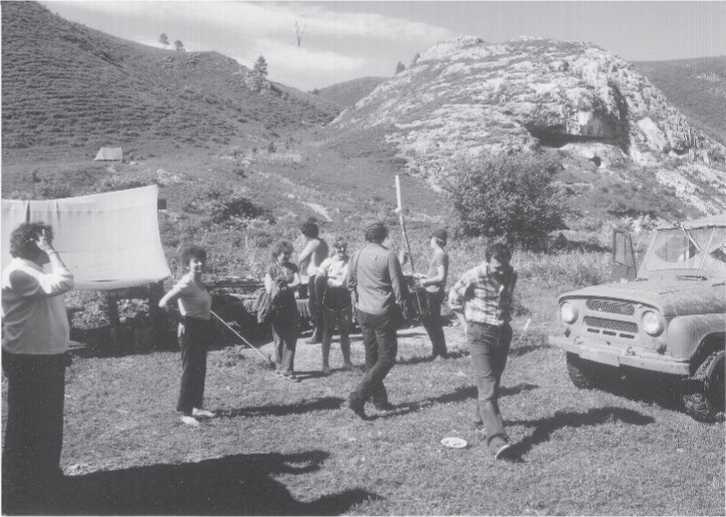

Fig. 3.89 Okladnikov Cave. Archaeological field camp. The south-facing cave entrance is visible in

The distant limestone outcrop in the upper right of the photograph. Left to right: Jacqueline Turner, Olga Pavlova, crew members, and Sergei Markin at far right. The road from Denisova camp to Okladnikov camp was very muddy, as the Soviet-era jeep shows (CGT color Okladnikov 6-13-87:32).

Portion of the distal end remained unchewed. It is kept temporarily in Ovodov’s Krasnoyarsk apartment and home office, a not uncommon practice since Russian scholars do much of their work and writing at home. Ovodov had originally identified in 1985 the child’s upper arm bone among the animal remains he found in Sibiryachikha VI. The present authors, having no experience with morphology or age-related robusticity in fossil human osteological remains, are unable to say whether it represents an anatomically modern human or a more archaic variety, nor can we identify precise age or sex, although we can say that there was no obvious pathology such as osteomyolitis or fTacture. As for finding human remains in Okladnikov Cave, Ovodov related in August 2006 a curious story about human bone fragments and teeth from this site that have created so much controversy that we review the discussion at the end of this section.

One summer during the period that Petrin was field supervisor for the Okladnikov Cave excavations, ten large bags, 25 kg each or more, of washed bone were trucked back to IAE for identification. Ovodov had time to examine the contents of only one bag that winter, and in the faunal content he identified ten pieces of human bone and teeth. These obviously had not been recognized in situ during excavation, which suggests that there is a strong possibility that the other nine large bags of bone contained additional human material. The really curious part ofthe story is that a decision was made to take the bags of bone back

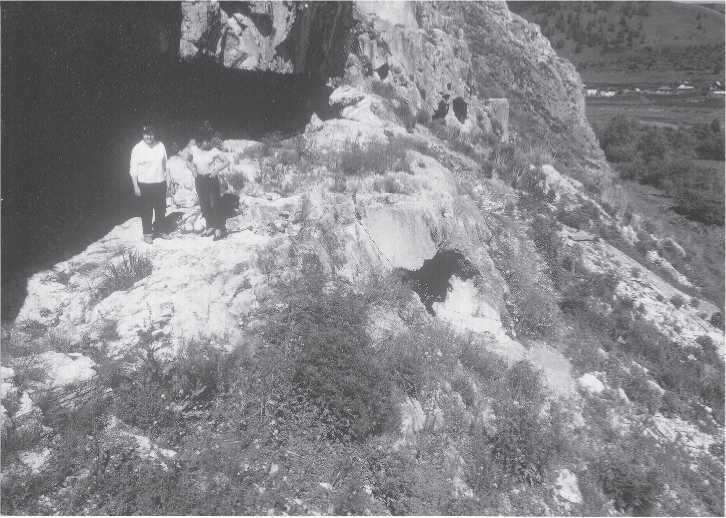

Fig. 3.90 Okladnikov Cave entrance. Jacqueline Turner (left) and Olga Pavlova stand on the 40 m long “cap” area that makes up the cave’s ledge entrance. Sibiryachikha village is in the distance at the upper right (CGT color Okladnikov 6-13-87:14).

To the Altai field camp and study them there the following summer. At some point in time after they arrived at the institute, all the large bags of bone were misplaced, forgotten, or lost. The amount of missing bone must have numbered in the thousands of pieces, as it is common for a small 20 x 30 cm plastic bag to contain several hundred small pieces. This loss is, of course, significant to late Pleistocene Siberian paleontology and physical anthropology, especially in light of the controversy stirred up by the two Okladnikov teeth that were saved by Ovodov’s careful examination. We emphasize careful because in the million or so pieces that we have examined during this project, we never found a piece of human bone or tooth fragment that had been missed by Ovodov.

As elsewhere in the Altai, thin forests of conifer and birch today blanket the upper hillside slopes near Okladnikov Cave. The foothills and valley bottoms are carpeted with grasses and numerous species of annual and perennial flowering plants, neatly trimmed by the grazing of the gentle village dairy cattle. Logging for village house and barn construction has increased the area of meadow plant growth. With help fTom Molodin, the senior author, along with his late wife, Jacqueline, and Olga Pavlova, made a one-day visit to Okladnikov Cave on June 13,1987. Markin was the field supervisor, and he led the senior author into the low tube-like, narrow depths of the ring gallery to where a final small shallow excavation was being completed. The very narrow, low ceiling, barrow-like damp and pitch-black condition of this part of the cave seemed a most unlikely place for human occupation. The small amount of archaeological stone and bone debris then being recovered seemed at the time to have probably been shifted by animal activity from its original place of deposit nearer the entrance. There were abundant carnivore tooth marks on the bone fragments. This bioturbation by cave-using animals would be seen repeatedly in other Siberian cave sites. Refuse concentration indicates that most of the human use of the cave was immediately outside, on the ledge (called the “cap”) of the protective rock shelter fTom which one enters the cave proper. Nearly 4000 stone items (tools and debitage) have been recovered from this ledge area and the talus slope immediately below. Various analyses of the Okladnikov Cave finds have been done by Ovodov (1987b), Derevianko and Markin (1992), Derevianko et al. (1998a), Ivleva (1990), Kulik and Markin (2003), Martynovich (1998), and others. No differences in tool types could be recognized in the various Pleistocene stratigraphic levels. One item of concern not mentioned in these reports is the fact that the large (25 kg or more) bags of faunal remains mentioned above were never studied. The few human bones and teeth identified by Ovodov were transferred to T. Chiksheva, who in turn loaned them to Academician V. P. Alexeev, Moscow. By a clandestine arrangement, the senior author, accompanied in 1987 by A. K. Konopatski and Jacqueline Turner, briefly examined in Alexeev’s Moscow apartment the teeth fTom this collection, leaving them in the possession of Alexeev’s wife, Tatyana Alexeeva. Following the death of Alexeev, the Okladnikov Cave human remains have been transferred to a German laboratory for DNA analysis, and at some point in time the teeth were examined by E. Sphakova. The paper trail for the transfer and storage of these few bones and teeth would not be acceptable in modern forensic practice. We have not been able to locate any photographs or catalog numbers of these Okladnikov Cave bones and teeth. As of this writing, their location is unknown.

Vasil’ev et al. (2002:521) inventoried the published carbon-14 dates for the Mousterian assemblage at Okladnikov Cave (Layers 1-3). The range is from >16 210 BP to 43 300 BP. These extreme values are based on bone specimens from Layer 3. There is a Layer 1 date of 33 500 BP. The senior author carried back to the United States a midshaft segment of a bovid leg bone excavated by Markin from near the bottom of the Okladnikov Cave midden. On his July 1987 return to the United States, Turner requested a uranium series date of the bone by the US Geological Survey, Menlo Park, California. This was generously provided by J. L. Bischoff. The date Bischoff obtained was ca. 33 500 BP, well in line with the carbon-14 dates from Okladnikov Cave, published 11 years later by Derevianko et al. (1998i), and with other radiocarbon dates for the late Pleistocene occupation of the Altai. Vasili’ev et al. identify no Upper Paleolithic dates for Okladnikov Cave. Temporally and typologically (dental morphology) the humans who used the cave were Mousterian culture-bearing Neanderthal-like people.

World History

World History