If you can run, shoot and dig a hole, you ve got the makings of a good infantryman: Ptejim BRYANT

When the war clouds of the impending European conflict finally reached Australia on 4th August 1914, the response from the fledgling nation was unequivocal. The outbreak of war was not unexpected as the deteriorating relationships between England, France and Germany made war almost inevitable. The subsequent call to arms in defence of the Mother Country met with an enthusiastic response from the newly formed Australian nation. Thousands of men from all walks of life and from all parts of the country responded to the call, and enlisted in the Expeditionary Force. To suggest that Australia would not enter the war in support of England would have been seen by the overwhelming majority of citizens as an act of extreme treachery.

Even before war was declared, military preparations were under way in the large Victorian town of Ballarat. On the cold Sunday evening of 2nd August, Lieutenant Colonel William Bolton, the Commanding Officer (CO) of the 70th Infantry, a Citizen Forces battalion, was at home reading by the fire, when at

10.30 pm he received a telephone call from Army Headquarters (HQ) at Victoria Barracks, Melbourne. Bolton was instaicted to report to Victoria Barracks at 10 am on the following morning, as war was imminent and his battalion could be mobilised. During the train trip to Melbourne, Colonel Bolton engaged in conversation with a fellow passenger. Sir Alexander Peacock, the Chief Secretary, and later the Premier of Victoria, who offered the opinion, that if war was declared, it would only last six months because of the prohibitive cost.

Upon arrival at Victoria Barracks, Colonel Bolton received orders to mobilise the 70th Infantry, and proceed to Queenscliff with the role of defending the forts covering the entrance to Port Phillip Bay. Having received his instructions, Bolton then made his way to the State Government Offices and made arrangements to hand over his civilian duties as from the next day. Once these arrangements were completed, Bolton returned to Ballarat by train. When he reported for full time duty at the orderly room of the 70th Infantry at 9 am on 4th August, Colonel Bolton’s immediate task was to organise the mobilisation of his battalion. News of England’s declaration of war reached Australia on the morning of 5th August, and later that day the Commonwealth Gazette formally proclaimed

The outbreak of war. Once the state of war was public knowledge, the citizens of Ballarat quickly responded to the situation. Colonel Bolton was surprised and delighted when Mr Jasper Coghlan came to the unit HQ and offered the use of his car and petrol to the unit, free of charge. With the aid of Coghlan’s car, Bolton and his staff, had by that same evening, gathered all the transport wagons, horses, drays and water carts, and assembled them in Ballarat’s Market Square.

By 6th August, pack animals had been purchased to carry the unit’s machine guns, and later that day, the Senior Constable from the Police Station at nearby Kingston, arrived with a fine Police horse for Colonel Bolton, courtesy of Sir Alexander Peacock.

At 11 am on 7th August, the 70th Infantry boarded the troop train at Ballarat and journeyed to Queenscliff. The train stopped at Geelong to pick up other members of the battalion. The 70th (Ballarat) Infantry, had its HQ at Ballarat, but also had training depots at Ballan, Gordon, Sebastopol and Buninyong. When the train reached Queenscliff at 3 pm, the troops unloaded the stores and equipment from the train and marched to their camp site. On the next day, Bolton’s force was augmented by the arrival of Lieutenant Colonel McVea and the 46th Infantry (Brighton Rifles).

The main task of the two battalions was to protect the Queenscliff Fort against any enemy attack, particularly from the direction of Barwon Heads. This required the posting of sentries and the digging of a 600 yards long trench across the main road to Geelong. All traffic had to be stopped and scrutinised by those on duty at the check point. This procedure led to one incident which could have had fatal consequences. A car load of civilians from Queenscliff failed to stop at the check point, whereupon the jittery sentries riddled the - car’s tyres with bullets. Fortunately, no other harm was done to the car or its lucky occupants.

An incident of some international significance occurred, involving the German cargo ship Pfalz, which had left Victoria Dock on the morning of 5th August, blissfully unaware that war was about to be proclaimed. The Pfalz was halted by a shot over her bows from a gun at Fort Nepean at about 11 am, and although it was not known at the time, that shot was probably the first shot fired in the Great War. Colonel Bolton was later requested to place a guard of 12 men on board the captured prize. The crew were taken off and escorted to the orderly room of the 70th Infantry at Geelong. Two days later. Colonel Bolton was ordered to check on the condition of the prisoners held at Geelong and report back to HQ in Melbourne.

Almost a week after the 70th Infantry commenced guard duties at Queenscliff, Colonel Bolton received orders to report to Army HQ at Victoria Barracks. Upon arrival he was somewhat surprised to find three of his contemporaries already at

The office of Colonel JW McCay, the former Federal politician and prominent Citizen soldier. McCay had played a significant role in the development of the embryonic Australian army whilst he was Minister for Defence in the Australian Government in 1904-05. Apparently Lieutenant Colonels Wanliss, Semmens, Bolton and Elliott had been selected as the Commanding Officers of the four battalions of the Victorian 2nd Infantry Brigade under the command of Colonel McCay, which was part of the Expeditionary Force about to be formed. McCay told his officers that Wanli. ss was to command the 5th Battalion (to be recruited from Melbourne); Jim Semmens, the 6th (also from Melbourne); Harold ‘Pompey’ Elliott, a DCM winner from the Boer War, was to lead the 7th Battalion (to recruit from northern Victoria); and finally, Bolton was to command the 8th Battalion.

I William CO 1914

Bolton,

1915

The fundamental unit of an infantry division is the battalion. Each infantry battalion was commanded by a lieutenant colonel and consisted of a Headquarters (HQ), a Machine Gun Section, and eight companies, designated from A to H Company. The companies were usually commanded by a major or a captain and had a strength of just over 100 men. Each company consisted of two platoons led by a lieutenant or second lieutenant. This gave the battalion an overall strength of just over a 1000 men. Each of the battalions were allocated to an infantry brigade on the basis of four battalions to each brigade, and the three brigades formed the fighting strength of the division. Although there were other essential units in the division such as artillery, medical, engineers and signals, the main manpower requirement within the division was for fit men for the fighting infantry battalions. Therefore the majority of men to be recruited would be allocated to one of the twelve infantry liattalions that made up the 1st Au. stralian Infantiy Division of the Australian Imperial Eorce lAlEj.

Bolton was directed by McCay to set up his main recruiting office in the 70th Infantry’s HQ at Ballarat, with a view to obtaining his recruits from Ballarat and its nearby districts, and the Western District of Victoria. Other recruiting offices were established at the Surrey Hills drill depot, Geelong, Ararat and at local police stations in the less populated areas. As CO of the 8th Battalion, Bolton had the right to choose his officers, subject to approval from Victoria Barracks. As soon as the meeting with his Brigade Commander had ended, Bolton returned to Queenscliff and at the conclusion of the church parade, he addressed his battalion. He spoke to them regarding the formation of the Expeditionary Force and then invited them to join the 8th Battalion which would

Be under his command. This invitation was accepted with alacrity by many of his officers and NCO’s. Although some 32 members of the 70th Infantry enlisted as a result of his appeal, including Leo Haggar the popular regimental bugler, Colonel Bolton was not entirely happy with the response. “The very small percentage of existing Citizen Forces volunteering for service was disappointing.” The officers from the 70th Infantry who volunteered and were appointed to the 8th Battalion included; Colonel Bolton, Captain Dale, and 2nd Lieutenants Paul, Catron, Close, Dalton and Findlay. Colonel Bolton selected his battalion officers from the Citizen Forces on the basis of his own “personal knowledge of their qualifications extending over a considerable period.”

Later that day. Colonel Bolton handed over command of the Queenscliff force to Colonel McVea, and then returned to Ballarat, where he immediately appointed Lieutenant Norman Dalton as the unit Recruiting Officer. Major Julius Lazarus then assumed command of the 70th Regiment.

The call to arms for men to enlist and fight to save the Mother Country, had an immediate effect. Droves of men made their way to the nearest recruiting office, usually the local drill hall. One of the first men to enlist at Geelong was the 20 year old Bill Groves, who later recalled the event:

We were having tea when I told my Mum “I’m going over. ” She pleaded with me not to go but I said, “Well I’m out of work and I’ll get paid seven days a week. ’’ So she gave in.

The diversity of the 8th Battalion is revealed when a clo. ser examination is made of its origins. l65 volunteers from various Victorian Citizen Forces units were allocated to the 8th Battalion. While the HQ of the battalion included a goodly proportion of officers and men from Bolton’s 70th, the eight rifle companies recruited from the following sources: A Company commanded by Honorary Lieutenant Colonel John Field, recruited from the Ballarat area which of course included a number of men from the 70th. Captain Frank Dale’s B Company consisted of soldiers from the Geelong area and included some volunteers from the 70th and 71st Infantry. C Company consisted of men from the Creswick, Geelong and Ballarat districts, supplemented by a few men from the 71st and 73rd Infantry. D Company (Captain John Sergeant) was a very mixed company with men from Colac, Ararat, Hamilton, Melbourne, Maryborough and the Wimmera. Most of the Citizen soldiers in D Company came from the 71st, 72nd, 73rd and 81st Infantry. Lieutenant Gerald Cowper commanded E Company, which was rai. sed from the Ararat, Stawell and Horsham areas, and included 22 men who had enlisted from the 73rd Infantry (Victorian Rangers). F Company, led by Captain Gus Eberling, also included a few Citizen soldiers from the 73rd, and was recruited mainly from the Mildura and Warracknabeal areas. In contrast to the other companies which were rai. sed in country di. stricts. Captain William Hodgson’s G Company was a company recruited from the Canterbury, Surrey Hills and Box Hill suburbs of Melbourne, and included 22 members of the 48th Infantry. The eighth company of the battalion was H Company, commanded by Captain Graham Coulter. Although this company had 15 men from the metropolitan 48th Infantiy, most of the recruits came from Gippsland towns such as Sale, Wonthaggi and Korumburra.

Capt "WF Hodgson, OCofGCoy.

The composition of the crriginal 8th Battalion was an interesting mix of country and city recruits. Although it is widely assumed that the 8th Battalion was a largely a Ballarat battalion, an examination of the embarkation rolls shows it included 159 men from Melbourne, and from areas as far apart as Mildura, Geelong and South Gippsland. The Ballarat compcrnent accounted for about a fifth of the unit’s strength. The average age of the officers was 31.65 years; NCO’s - 25.38 years; privates -23.92 years. Almost 92% of the battalion were unmarried, while the percentage of officers and men who joined the AIF from the Citizen Forces was only 16%, a figure which was well below the Government’s rather optimistic expectations of a force of which at least half the members would have had previous military service. The 8th Battalion had the highest proportion of officers in the entire 2nd Brigade, who had .served in the Boer War or other overseas campaigns. The. se included Lieutenant Colonel Gaitside, Captains Sergeant and Coulter, Lieutenants Cowper, Ebeiiing and Trickey. In addition, there were a number of NCO’s and men who had afso. served in the Boer War, thus providing a very necessary leavening of experience within the unit.

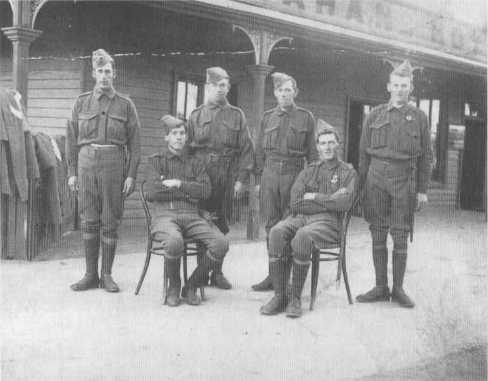

The ‘Ballan Boys’ 1914

Back row L-R; Alf Anderson, William Lewis, Andy Ward, Ted Lay. Front row L-R; Alf Day, Perc Lay.

The official outbreak of war between Great Britain and Germany was announced by the Australian Prime Minister Mr Jo. seph Cook, on 5th August 1914. The Australian Government immediately offered to rai. se an expeditionary force of 20,000 men to assist Great Britain, and this offer was accepted with great alacrity on 6th August. Heeding the advice of Brigadier General William Bridges, the Inspector General of the Australian

Army, the Australian Government insisted that the expeditionary force consist of an infantry division, in order that the newly emergent national identity as Australians be maintained.

Recruiting for the Expeditionary Force, which was designated the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), officially opened on 14th August, and in those first few heady days, thousands of men throughout the nation came forward to enlist in the army. Three days later. Colonel Bolton reported to Victoria Barracks only to be confronted by an amazing scene:

/ found a large number of men assembled in the Barrack square who had been enlisted and posted to the various battalions. General Bridges [the commander of the 1st Australian Division] and Colonel McCay were present and the former officer addressed the neuclei of the Brigade and then handed over to their battalion commanders. I found in my command there were between 200-300 men; all had their few personal belongings in small suit cases, swag and even sugar hags and the look of a fine hardy looking crowd.

Typical of the many recruits who enlisted in mid-August, was Jim Bryant, a farmer who worked on his father’s property at Glenorchy. Bryant recalled the night that news of the outbreak of war reached the property.

After we knocked ojf shearing one night a message came...that war had broken out between England and Germany. I immediately said “I'm going”. I remember one chap said “Can’t you wait until you get an iron plate riveted over your behind?” I think a lot of us loved England. I think we felt more affiliation towards Britain at that time tha n 1 did to A ustralia. '

Bryant’s reaction was not unusual, as many Australians still thought of themselves as Victorians or Queenslanders, rather than Australians, particularly as Federation of the Colonies had only occurred in 1901. When Bryant was only a boy of 9 or 10, he watched in awe as the. soldiers returning from the Boer War were welcomed at the small country railway station. “I thought they were Gods”. It was this lasting childhood impression that preempted Bryant to immediately enlist. It has since been argued that the blooding of the Australians at Anzac Cove on 25 April 1915, was the catalyst that created a sense of nationhood, not only among the troops, but also back in Australia. Certainly the Gallipoli campaign cemented the bond of nationhood, and to a large extent di. ssipated the strong parochial State identification. By the time the troops finished training at Broadmeadows, the. strong unit and personal bonds were well established.

With the help of several of his officers and some NCO’s, the new recruits were formed into several company sized groups, and in conjunction with the other battalions, the motley hotchpotch of suit case-carrying civilians and uniformed men, commenced the 12 mile march to the new camp at Broadmeadows. From

Victoria Barracks, the columns crossed over Princes Bridge, left along Flinders Street and along Elizabeth Street, past Melbourne University and on to Broadmeadows. As his battalion marched along Elizabeth Street, cheered on by thousands of well-wishers. Colonel Bolton noticed a giant German sausage hanging from a pole outside a butcher’s shop, and embedded in the sausage was a huge butcher’s knife - a symbolic gesture of support for the Expeditionary Force. Captain Catron later observed that “Men who dined in expensive hotels the night before were now enjoying hot dogs.”

Two of the early volunteers, both of whom lacked prior military training were Edward and Percy Lay from East Ballan. Percy was to go on to become the most decorated soldier in the 8th Battalion, but at this early stage they were off to Broadmeadows as Edward put it, “to learn soldiering.”

As the rather tired, but enthusiastic 2nd Brigade, reached Broadmeadows, each unit was directed to its camp area. When the 8th Battalion arrived at its designated spot, the men were surprised to find that a large marquee, which was to serve as the Orderly Room and temporary QM Store, had been erected adjacent to the parade ground. This marquee had been erected by the RSM, Dan Weeks and his small advance party. Weeks had been RSM of the 70th Infantry, and his CO was delighted to have as his RSM, an experienced soldier who had seen 20 years service in India. Colonel Bolton acknowledged that Weeks was a key figure in the 8th Battalion; “His knowledge and experience and fine character were invaluable to me in the early stages of training.”

Private Joseph Lugg described the march to Broadmeadows and his early days in camp:

The streets of the city were lined with people. I never saw such a crowd of people since the American Fleet and Ballarat was cheered all the way along. We find the bed a bit hard, but I am in with some good chaps so it is alright. One of our chaps measures 6 ft 4" in his socks, and we call him Tiny.

The rest of that first day was spent in erecting tents to accommodate not only the troops who had just marched in, but also the additional troops who were to be enlisted over the next few weeks in order to bring the battalions up to their full establishment of about 1000 men. Each man was issued with his blankets and sufficient straw to fill a palliasse. The 8th Battalion was located in the eastern part of the camp near the Broadmeadows Railway Station, which was furthermost from the Divisional HQ and Q Store. The difficulties posed in transporting supplies and equipment to the battalion site led Colonel Bolton to suggest that “the camp site was totally unsuitable for a standing Military Camp.”

The official historian, Charles Bean was to later enthuse over the natural military skills and the fine physique of the AIF, however, this view has recently been criticised by some revisionist historians. The composition of the 8th Battalion,

Certainly fits Bean’s stereotype. The majority of the original members of the battalion came from farming and country areas, most could shoot, many could ride a horse and were well used to the rigours and hardships of life in the bush. Unlike many AIF battalions, the 8th Battalion also had a significant number of men who were gold miners, having come from Ballarat and areas such as Daylesford. Even the metropolitan battalions, where one would expect a higher proportion of men from more sedentary occupations, many men had at some time indulged in the pursuit of rabbits and could shoot accurately. Colonel Bolton was to later comment that the 8th Battalion’s shooting prowess was “largely due to having officers and NCO’s who had been active members of the Ballarat Regimental Rifle Club, and this proficiency in musketry was to be a vital factor in the battalion’s operations on Gallipoli.” The obvious advantage of a country ba. sed battalion such as the Eighth, was that the men were tough and already pos. sessed many of the required militaiy skills. Unfortunately, these independent skills mitigated against a rapid acceptance of military discipline, and on several occasions provoked serious incidents. Private Jim Bryant later recalled:

I bad good training for Gallipoli. Seeing I was brought up in Stawell, 1 could run. I was a farmer and so I could shoot and because we had no hull-dozers then, we could also make holes and excavate. We could all shoot like sniper, we could dig like wombats - digging rabbits from tbeir burrows was a busb kid's pastime.

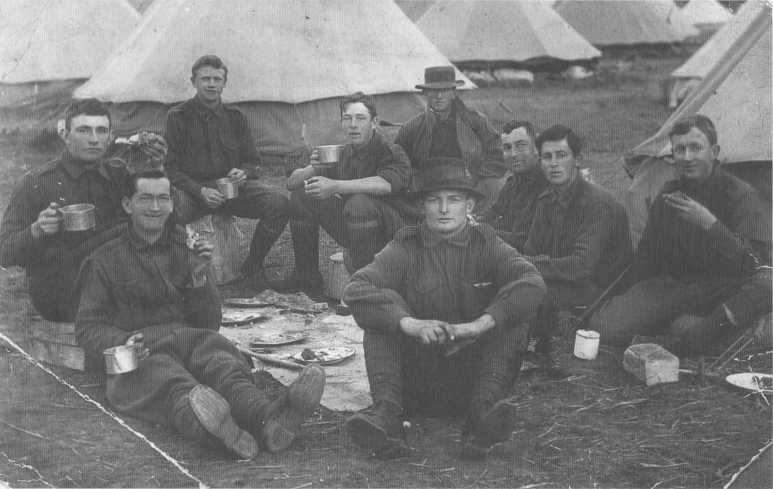

Members of E Company enjoying a meal at Broadmeadows. Pte HG Taylor, second from R.

D Company photographed at Broadmeadows Camp.

The Broadmeadows camp site which liad been generously provided by the good offices of a Melbourne citizen, was certainly not the perfect camp site. The close proximity of Broadmeadows to Melbourne and its ability to house the entire 2nd Brigade was viewed with some favour, but on the debit side, the black clay soil created many sanitary and drainage problems in rainy weather. Nonetheless, the training of the several thousand recruits soon got under way and Colonel Bolton noted that:

It was an inspiring sight to see the whole camp crowded with recnut squads and their drill instnictois going through the elementary’ training. Training was also necessarily hurried, [hut thej rank and file displayed remarkable aptitude.

The 8th Battalion was chosen to provide the first guard at the camp entrance, but at this early stage, the men had not had drill or rifle training. Lieutenant Joe Catron as guard commander, resolved the dilemma by calling for volunteers with previous military service to form the guard. It did not take too long to find 20 volunteers, and Catron then had the men issued with rifles and bayonets. A number of British Army Reservi, sts had already been training at Broadmeadows prior to the arrival of the 2nd Brigade, and were used to casually entering the main gate. That is, before Private Jack Kidney assumed the role of. sentry. Jack took his duties very seriously and Catron was startled to hear a bellowed challenge “Halt! Who goes there?” He mshed out of the guard tent to find that Kidney had bailed up one of the Reservists at bayonet point. Kidney’s enthusiastic lunge with his bayonet had pierced the Tommy’s greatcoat, and a tirade of abuse was being freely exchanged between the two men. Catron noted that he “learnt more about their ance. stors in five minutes than I thought could possibly be on a family tree.” When the Reservist had cooled down and retracted his abuse about Australians and the 8th Battalion, Catron permitted the cha. s-tened soldier to enter the camp.

The influx of additional recruits soon enabled the 8th Battalion to assume its organisational structure of a HQ and eight rifle companies (A to H). By mid September, Colonel Bolton received orders to close down his recruiting offices in Ballarat and in Melbourne. The closure of the Melbourne office was not achieved without the intervention of the CO. Apparently the officer in charge, Lieutenant DF Hardy, a recent Duntroon graduate just appointed to the 8th Battalion, rang Colonel Bolton and explained with some embarrassment that he could not report to the battalion as ordered, as the proprietor of the hotel would not permit him to remove his kit as the Army had failed to pay for his board and lodgings. Bolton then rang the hotel and soon reached an agreement with the proprietor which permitted Lieutenant Hardy to report to Broadmeadows Camp the next day.

On the same weekend, Colonel Bolton drove up to Ballarat to close down the recruiting office at the 70th Infantry HQ, and also spend some time with his family. He left Ballarat at 4 am on the Monday, with the intention of being present for the first parade. When he arrived at the 8th Battalion lines, he was shocked when greeted by his agitated second in command [2/IC], Honorary Lieutenant Colonel Robert Gartside, who explained that the battalion was in “a state of turmoil” following an inspection by a staff officer from Brigade HQ. Apparently the inspecting officer found some mbbish near two tents occupied by newly arrived recmits, and as punishment, the whole battalion was paraded before the Brigadier, who then had the unit marched down to the 5th Battalion lines. The men then underwent the humiliation of being marched up and down the tent lines of the 5th Battalion and publicly cautioned to keep their lines clean in future. By Monday morning, the men were in a mutinous mood, and the CO decided to parade each company in turn and address them. Colonel Bolton later paraded the entire battalion on the parade ground and as a consequence of this incident, the 8th Battalion became known throughout the 2nd Brigade as the ‘dirty Eighth’.

The issue of how to impose discipline on the independent Australian soldier was to cause problems both in camp and several months later in Egypt. Shortly after the ‘dirty lines’ incident, a warrant officer of the 5th Battalion, returned to camp in an inebriated state. He was court martialled and sentenced to Field Punishment. The 5th Battalion was then marched past the warrant officer, who was spread-eagled on the ground with his hands and legs tied. This clumsy attempt at teaching the troops a salutary lesson created considerable anger in the ranks, and a potentially dangerous situation was only overcome by some prompt action by some officers and NCO’s of the 5th Battalion. Colonel Bolton was particularly concerned at the implications of such an incident and later wrote:

So much has been said and written about the lack of discipline in the

Australian soldier and this incident provides a striking illustration of

Members of F Company undergoing PT.

Pte RJ McPherson is in the second row, second from the R.

What NOT TO DO with a free horn Australian whose discipline and obedience can only he secured hy treating him as a man all the time, and having mutual consideration and respect throughout all ranks produces the very' strongest and finest form of discipline under all conditions.

The close links between the the 8th Battalion and Ballarat, its main recruiting area were particularly strong and remained so for the duration of the war. The battalion had been in camp for some weeks, when Colonel Bolton and his unit received an invitation from the Lord Mayor and Councillors of Ballarat to attend a civic function to honour the battalion. Following a request from Colonel Bolton, the Defence Department agreed to provide a special steam train to transport the battalion to Ballarat for the function. Upon arrival at the Town Mall, the troops found that it had been decorated, and when the men sat down at the tables, the young ladies of Ballarat came out and seiwed dinner. Formal speech making was kept to a minimum, and the evening concluded with the Lord Mayor, Councillor Isaiah Pearce, wishing the 8th Battalion, “God speed and good luck” and requesting them to bring back the head of the Kaiser on a charger.

The departure of the battalion from the Ballarat Railway Station on the next morning led to some remarkable scenes as recalled by Colonel Bolton:

All the city seemed to be there, the sweethearts and wives, mothers and fathers formed a vast throng. Crowded all the platforms and connecting bridges and even flowed on to the rail tracks to such an extent the driver of the engine refused to start and I remember well, I had to walk in front of the engine and beg the people to move to one side whilst the train slowly crept along until clear of the station when I jumped on the running board and got into a carriage. Many of those affecting good byes were the last thing they ever saw of their loved ones.

Camp life was a reasonably leisurely affair, despite the drill and tactical training. Contact with family and the outside world was maintained due to a policy which permitted visitors to enter the camp each afternoon at 4.30 pm, and on Sundays after the conclusion of the Church Parade at 11.30 am. The close proximity of the camp to the Broadmeadows Railway Station, meant that on Sundays the site assumed a carnival atmosphere rather than a strict army camp. The thousands of visitors, including those who had come from country Victoria to see their sons and husbands, usually brought with them delectable food. In the words of one soldier:

The visitors would bring enough fruit and cakes to last the following week; and how we looked forward to Sundays! - they were red-letter days for all of us.

By early October, the troops were anxiously awaiting some news regarding their departure for foreign shores. Training had progressed from drill and rifle training to tactical exercises, and on 11th October, the 7th and 8th Battalions of Yellow Force, left the Broadmeadows Camp at 2 pm, and took up a defensive position around the Thomastown Railway Station. The opposing Pink Force consisted of the 5th and 6th Battalions, supported by the 2nd Field Artillery Brigade. Despite the bitterly cold conditions, the men of Yellow Force were up at 2 am, and later eagerly marched out to meet their attackers. One soldier from the 8th Battalion described the training:

We manoeuvred and skirmished, day in day out; we charged hill after hill, held by imaginary Germans; we always managed to win, and strange to say, we never lost a man.

The warmer weather of early October, introduced a minor public relations problem. Apparently, some soldiers had been bathing in the nearby Merri Creek, a practice which led the indignant local residents to complain that the soldiers were “walking about in a nude state”. The outraged locals were soon placated when nude swiming in the Merri Creek was prohibited. Many of the supply problems that plagued the battalion’s first two months at Broadmeadows, were not resolved until mid October. The wide range of sizes within the AIF made it

Lt Col WK Bolton (L) and a junior officer on manoeuvres.

Difficult to immediately fit all soldiers with necessities such as greatcoats and boots, and the cold, wet weather only compounded the problems. In addition to the regulation slouch hat, all men were issued with the British Territorial Army pattern peaked cap, which was worn by many men in preference to the slouch hat. Joe Lugg wrote to his parents expressing his frustration at the delay in sailing for the front:

1 think we will he going very soon now and I will he glad as it is about time to go and get done with the joh. / have promised nothing hut to do my duty. I did not come here to talk, hut to do and that is what I'm expected to do.

World History

World History