With the signing of the November armistice, it might have been thought that peace had come at last to the war-ravaged peoples of Europe and afar. For some, however, peace was not yet to be; indeed, at this very time, revolutionary turbulence was sweeping Germany and Hungary as part of the seismic shock engendered by the Central Powers’ defeat while Moscow w'aited in the wings, gloating that the world revolution was imminent. ¦ However, both the German and the Hungarian revolutions misfired. Their eventual successors were the liberal but in many respects ineffectual W’eimar regime in Germany, and the reactionary regency of Miklos Horthy in Hungary, whom the break-up of the Habsburg Empire had left in the unenviable position of being an admiral without a seaport at his disposal. For a time half of Europe trembled on the brink of chaos or shook with fear in anticipation of the effects of the coming new order. Yet European institutions survived; the

Tidal wave passed. However, to a great degree the whole of the 1918-19 peacemaking process was carried out in the shadow of revolution and the consequent desire of the victors to shield themselves from its effects.

The Treaty of ’ersailles was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the Sarajevo assassinations, in the Galerie des Glaces (Hall of Mirrors) of the Palais de Versailles, where the German Empire had been inaugurated in 1871 in the heady aftermath of Prussia’s victory over France. In the middle of the Galerie, the plenipotentiary delegates were gathered round a horseshoe table, in front of which - ’like a guillotine’, as Harold Nicolson wrote in his dairy - was the table for the signatures. In addition, the Hall of Mirrors was filled with over a thousand seats for members of delegations and other distinguished guests.

As Whlson and Lloyd George slipped into their seats, Clemenceau glanced to right and left, then signalled for silence. Over an awed hush, the French Prime Minister commanded, 'Faites entrer les Allemands' (Bring in the Germans).

Through a door at the end of the vast hall emerged the German delegates, Muller and Bell. Their faces were ashen with emotion. After the Germans were seated and Clemenceau had declared the session open, Muller and Bell quickly rose to their feet, anxious to sign and complete the ordeal, only to be motioned to sit down again. After further preliminaries the two Germans at last were led to a small table where, at 12:03 p. m. precisely, they put their signatures to the treaty. As other delegates formed a queue to approach the table and sign, a thunderous salute boomed forth outside, and in the distance the cheering of the Parisian crowd could be heard.

In a surprisingly short period the signing was completed. '’La seance est levee,’’ said Clemenceau. According to Nicolson, Muller and Bell were ‘conducted like prisoners from the dock, their eyes still fixed upon some distant point of the horizon’. The ceremony was over, the delegates had dispersed. But the story of Versailles had hardly begun. The Treaty of Versailles, 200 pages in length, comprised 440 articles. Its main provi-.sions are summarized below:

Germany was required to surrender Alsace-Lorraine, its borders limited to those in existence in 1870, to France; most of West Prussia and Posen (Poznan) and much of East Silesia and East Prussia to Poland; and part of Upper Silesia (Teschen) to Czechoslovakia. In addition she was to yield Moresnet, Eupen and Malmedy to Belgium and Memel (Klaipeda) to Lithuania. As a result of a plebiscite held in Schleswig, the northern region returned to Denmark and the southern region remained with Germany. On the Baltic Sea, the German city of Danzig was to be created a free city under the League of Nations; although France had wanted Poland to annex Danzig outright, she managed to have the city wrested forcibly from the Reich. Germany was to lose all her colonies, and the Reich ‘acknowledges and will respect strictly the independence of Austria’, as Article 80 of the treaty forbade a German-Austrian union {Anschluss). Plebiscites were to be held to determine the fate of Upper Silesia, as well as Allenstein.

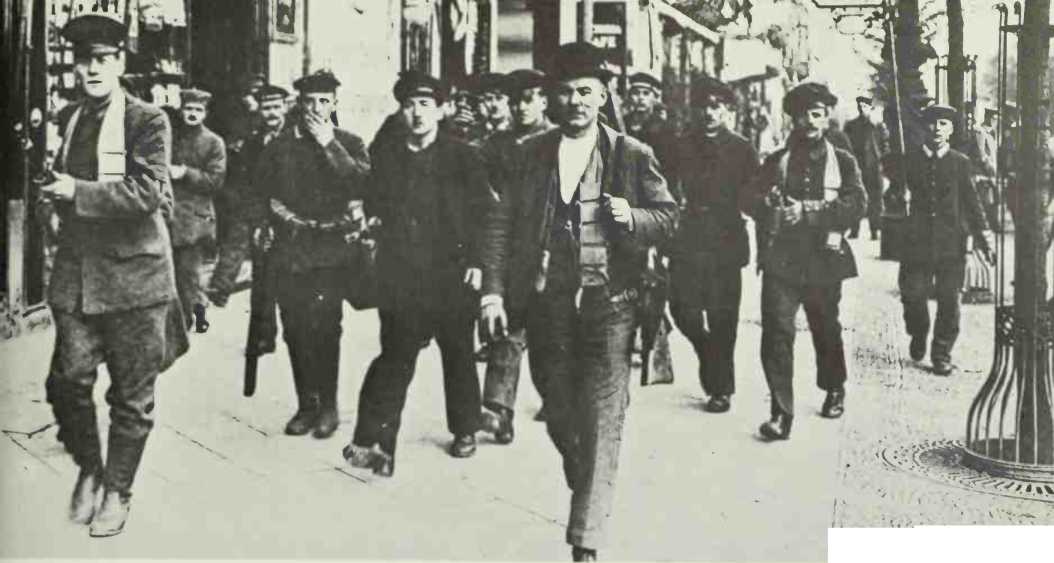

Protection troops of the nevs'ly-appointcd Workers’ and Soldiers' Council march down the L'nter den Linden.

Olszlyn and Maricnwcrdcr (Kwidzyn) in Hast Prussia. .-s a result, almost all of the latter two territories remained with Germany, but in the final settlement the smaller and richer part of Upper Silesia passed to Poland. These changes caused Germany to lose about 13-5 per cent of its tcrritor- and economic potential, and about to per cent of its population.

The 'ersailles Treaty contained many other provisions. Germany was forbidden to fortify a large section of the Rhine. The. Allied occupation of the Rhineland was to proceed as described earlier. The German army was to consist of not more than 100,000 ofTiccrs and men, the navy of not more than 15,000. There was to be no German air force. The General Staff as such was abolished, and no staff college w:ls to be maintained. Conscription was forbidden.

The most controversial part of the treaty concerned Article 231, the so-called war guilt clause. This stated that:

The Allied and. Associated Governments affirm and Germany accepts the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed on them by the aggression of Germany and her allies.

Such was the Treaty of Trsailles, a treaty which satisfied few men except the rulers of the succession states of Gcntral-Kast Europe. Otherwise the settlement was tcx> harsh for the British go eminent, but too soft for the French. Wrsailles was not Utopian enough for Wilson, yet too Utopian for some cynics, fhe Germans rejec ted the entire concept of a diktat dictated peace, which underlay the peace conference.

I he fJreat War was the most destructive conflict which the world had yet seen. Its toll of lives w. LS srj vast as to dc'fy imagination. Givilian deaths, apart from the influenza pandemic.

Amounted to at least 9,000,000, though some writer's have set the figure at more than 12.6 million. Military loss of life is calculated at oer

8,000,000, broken down as follows:

Germany Russia France

Austria-Hungary Great Britain Italy Turkey British Empire United States * Total 1,010,000.

If w e include figures for wounded, prisoners and missing, total military casualties were about

37,500,000 over 22,000,000 for the Allies, over

15,000,000 for the Central Powers.

It has been estimated that the total economic cost of the war was /j75,o77,ooo, ooo (over $375 billion), of wdiicli the Allied governments s|ienl /)7,852,000,000 and the Central Powers

13,476,000. 'Fhe price paid in physical devastation was greatest on French territory: 1,875 scjuare miles of forest destroyed, along with 8,000 square miles of agricultural land and about a quarter of a million buildings.

'Fhese are cold statistics, and the reader may not sense from them the disillusionment that percolated downwards as ordinary peo|)le realized slowly the horrendous price which they had paid for a reordering of the woi Id’s afiairs w hich was proving unsatisfactor) at best. Plenty of men and organizations were waiting on the sidelines to harness and ex|)loit this sentiment. 'Fhe heirs to this fathomless disappointment, this harvest of hroken dreams, were Fascism and Communism; pacifism and nihilism ; anarchism, fatalism, escapism or sheer apathy. No one ean understand how the world drifted into World War II almost in spite of itself without remembering the dejected legaey of World War 1.

KV.)

World History

World History