In order to pin down as many enemy forces as possible in the Argonne, small diversionary attacks were ordered for January 29, 1915;

And all regiments of the 27th Division were to participate. Following the blowing of a French mine shaft we had discovered, our regiment was to conduct a heavy raid in the 2nd Battalion sector on the right. While this raid was in progress our artillery would open up and pin down the enemy in the 3rd Battalion sector in front of the 10th Company, forward on the right, and the 9th Company, forward on the left. For this purpose a howitzer battery from the 49th Field Artillery was made available and it completed its registration on 27 and 28 January. Although the 10th Company would have to move from its position during the operation, the 9th Company was not to advance but was to cut off all enemy attempts to escape on the flank.

January 29 dawned cold with the ground frozen. At the start of the operation I was up forward in our new strong-point with three rifle squads. We were a hundred yards ahead of our positions and heard our own shells whistling overhead, some striking the trees, others landing to our rear. Then they blew the mine; and earth, sticks, and stones rained on the landscape. Hand-grenade blasts from the right and intense small-arms fire followed the explosion. A lone Frenchman ran up to our position and was shot.

A few minutes later the adjutant of the 3rd Battalion came up, reported that the attack on the right was going well, and said the battalion commander wished to know if the 9th Company cared to join in the fun. We certainly would! Anything to get out of these trenches and this continually having to take cover.

I realized that I could not move my company from our trenches in deployed formation, for enemy artillery and machine guns had our range and any advance on our part would be reported by his tree-top observers. To avoid this I had my men crawl up a trench that extended to the front from the right of our position. After they reached the end of the trail, they deployed to the left; and after about fifteen minutes the company was assembled in an area a hundred yards in front of our position and on the slope leading down to the enemy. Carefully we crawled through the bare underbrush toward the enemy; but before we could reach the hollow he opened on us with rifle and machine-gun fire that stopped us cold. There was no cover, and we could hear the bullets slam into the frozen ground. Up ahead a few oak trees sheltered a handful of my men. I could not locate the enemy even with my binoculars. I knew that to remain where we were would cost us dearly in casualties, for even though the enemy fire was un-aimed, it made up in volume what it lacked in direction.

I wracked my brains to find a way out of this mess without suffering heavy losses. It is in moments like this that the responsibility for the weal or woe of one's men weighs heavily on a commander's conscience.

I had just decided to rush for the hollow sixty yards ahead, since it offered a little more cover than our present location, when we heard the attack signal far off to the right. My bugler was right beside me and I had him sound the charge.

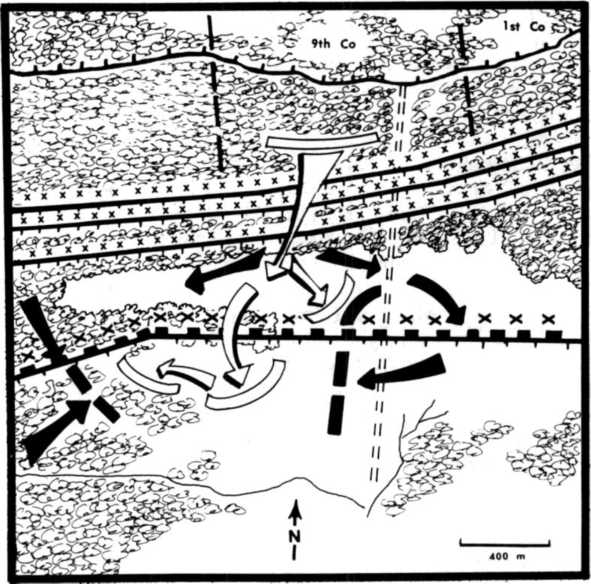

In spite of the undiminished volume of fire directed at us, the 9th Company jumped up and, cheering lustily, dashed forward. We crossed the hollow and reached the French wire entanglements only to see the enemy hurriedly abandon his strong position. Red trousers flashed through the underbrush and blue coat tails were flying. Totally oblivious of the booty left behind in the abandoned positions, we rushed after them. By sticking close to the enemy's heels we managed to smash through two other defensive lines which had been well provided with wire entanglements. At each position the enemy ran before we got to him. As proof of the meagre resistance, we had no losses whatever. (Sketch 11)

We passed over a height and the woods began to thin out. We could see the enemy running before us in a dense mass, so we pounded after him, shooting as we went. Some of the company cleaned out the dugouts, and the rest of us kept going until we reached the edge of the woods six hundred yards west of Fontaine-aux-Charmes. At this point we were half a mile south of our initial position. Here the terrain sloped down again, and the fleeing enemy had disappeared in low undergrowth. We had lost contact on both flanks and to the rear and on both sides we heard the sounds of a bitter struggle. I assembled the company and occupied the edge of the woods west of Fontaine-aux-Charmes and then tried to re-establish contact with the adjacent units. To the accompaniment of general laughter, a soldier brought some articles of feminine wearing apparel out of a dugout.

A reserve company arrived, and after giving it the job of re-establishing contact, we moved off down hill to the southwest through the light shrubbery of this sector where the terrain had been largely cleared of trees. My unit advanced in a column behind strong security elements. We had just crossed a hollow when strong fire from our left forced us to the ground, but the enemy could not be seen. In order to maintain our impetus, we moved off to the west, bypassed the hostile fire, and then resumed our advance to the south through open woods.

Sketch 11

Attack against the “Central” position, January 29, 1915.

At the upper edge of these woods we suddenly came upon a barbed-wire entanglement, the extent of which, we had never seen before. Some hundred yards in depth, it extended on both flanks as far as the eye could see. The French had also cleared the entire forest in this salient. On the far side of this obstacle, which was situated on a gently sloping rise, I could see three of my men signalling—one was Pvt. Matt, the youngest of our war volunteers— so it was clear that the enemy had not as yet occupied this strong position. It struck me, that to seize and hold this position until the reserves came up would be a worthwhile and important undertaking.

I tried to move on down the narrow path that led through the wire, but enemy fire from the left forced me to hit the dirt. The enemy was nearly a quarter of a mile away and certainly could not see me because of the density of the wire, yet ricochets rang all around me as I crawled through the position on all fours. I ordered the company to follow me in single file, but the commander of my leading platoon lost his nerve and did nothing, and the rest of the company imitated him and lay down behind the wire. Shouting and waving at them proved useless.

This position, constructed like a fortification, could not be held by three men alone, and the company had to follow. By exploring to the west, I found another passage through the obstacle and crept back to the company where I informed my first platoon leader that he could either obey my orders or be shot on the spot. He elected the former, and in spite of intense small-arms fire from the left we all crept through the obstacle and reached the hostile position.

To secure the position, I had my company deploy in a semi-circle and dig in. The position was called “Central” and was constructed in accordance with the most recent design. It was part of the general defensive system which ran through the Argonne and consisted of strong block-houses, spaced some sixty yards apart, from which the French could cover their extensive wire entanglements with flanking as well as frontal machine-gun fire. A line of breastworks connected the individual block-houses, and this wall was so high that fire from the fire step could reach any part of the wire entanglements within range. The wall was separated from the entanglement by a ditch some fifteen feet wide which was water-filled and, at this time of the year, frozen over. Deep dugouts were provided behind the wall, and a narrow road ran along some eleven yards from it. The height of the wall was such as to offer concealment to any vehicles using the road.

From the left we were subjected to considerable small-arms fire, while over on the right the installations appeared to be unoccupied. Around 0900 I sent the following written message to my battalion:

—9th Company has occupied some strong French earthworks located one mile south of our line of departure. We hold a section running through the forest. Request immediate support and a re-supply in machine-gun ammunition and hand grenades.”

Meanwhile the troops were trying to make an impression on the frozen ground with their spades, but it was only by using the few available picks and mattocks that we made any progress. We had been working for some thirty minutes when the left outpost reported that the enemy was retiring through the wire some six hundred yards to the east in closed column. I had one platoon open fire. Part of the enemy headed for cover, but others who were still north of the obstacle turned farther to the east and apparently reached the covered road behind the works, for very shortly after our opening fire we were attacked from that direction.

Since our digging was producing little worth mentioning, I looked for another place to locate the company. Two hundred yards to the right I found a bend in the enemy position which would serve as an excellent place to hold if we were to maintain our bridgehead in the enemy works. The company fought its way to the new position, called —Labordaire,” where we quickly improvised defences with the many tree trunks scattered about. From here, we opened a lively and independent fire against the enemy force on the right and brought him to a halt about three hundred yards away. He choose to dig in at that point and shortly thereafter his fire slackened and then ceased.

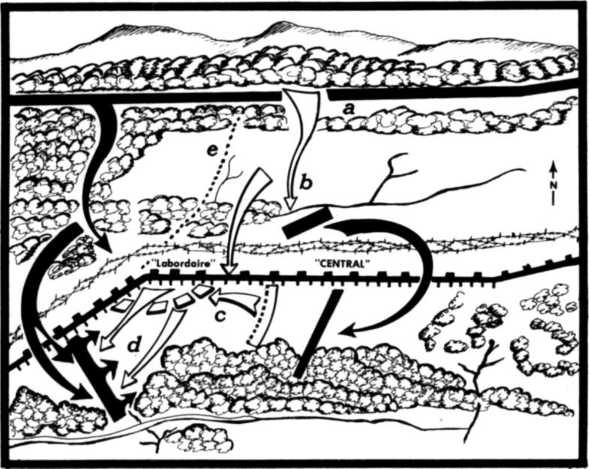

My bridgehead included four blockhouses, my company being deployed in a semicircle with a platoon of fifty men in concealed reserve between the wire entanglement and the position. Here another narrow zigzag passage led through the wire field. Time passed and we began getting anxious about our reinforcements and supplies. Suddenly reports from the right indicated that more French were retreating through the wire some fifty yards from us. The platoon leader wanted to know if he should open fire. What else was there for us to do? We were about to get into a nasty scrap, and there was no use allowing the French to start it free from casualties. If we fired at once, then the French would turn to the west and get into the position through the next passage; it was also possible that they might get across our line of communication and so surround us. I opened fire. (Sketch 12)

From the high French breastworks rapid fire struck the nearby enemy, and a bitter struggle developed, with the French fighting bravely. Fortunately most of the new enemy, estimated as one battalion, turned off to the west, traversed the wire entanglements 350 yards away, and moved toward us from the west on a broad front. The ring about the 9th Company closed leaving but one narrow path through the wire to connect us with battalion. Even that lifeline was swept by enemy fire from the east and west. On the right our heavy fire kept the enemy pinned to the ground, but the enemy on the left had made progress and was getting dangerously close. Ammunition was getting scarce, and I stripped the reserve platoon of most of its equipment.

Sketch 12

Attack against the “Central” position, January 29, 1915. View from the south, (a) Third French position, (b) 9th Company exploits the breakthrough and penetrates as far as the “Central” position, (c) 9th Company holds portions of “Central” and “Labordaire” positions, (d) Attack prior to breaking off combat, (e) Route of withdrawal.

I decreased the rate of fire in order to conserve ammunition as long as possible, but the enemy on the west kept crawling closer. What was I to do once my ammunition was exhausted? I still hoped for help from the battalion. Minutes passed like eternities.

A fierce battle raged around the blockhouse on the extreme right, and we expended our last grenades in its defence. A few minutes later, about 1030,

A French assault squad succeeded in taking it and used its embrasures to pour rifle and machine-gun fire into our backs. This report reached me at the same moment that a battalion order was shouted across the entanglement by a runner: —Battalion is in position half a mile to the north and is digging in. Rommel's company to withdraw, support not possible.” Again the front line was calling for ammunition, and we had enough for only ten more minutes.

Now for a decision! Should we break off the engagement and run back through the narrow passage in the wire entanglement under a heavy cross fire? Such a manoeuvre would, at a minimum, cost fifty per cent in casualties. The alternative was to fire the rest of our ammunition and then surrender. The last resort was out. I had one other line of action: namely, to attack the enemy, disorganize him, and then withdraw. Therein lay our only possible salvation. To be sure, the enemy was far superior in numbers, but French infantry had yet to withstand an attack by my riflemen. If the enemy in the west were thrown back, we would have a chance of getting through the obstacle and only have to worry about the fire of the more distant enemy on the east. Speed was the keynote of success, for we had to be gone before those we had attacked could recover from their surprise.

I lost no time in issuing my attack order. Everyone knew how desperate the situation was, and all were resolved to do their utmost. The reserve platoon drove to the right, recapturing the lost blockhouse and carrying the whole line along with its impetus. The enemy broke and ran. With the French running away to the west, the proper moment to break off combat had come. We hurried eastwards and negotiated the wire entanglement in single file as fast as possible. The French on the east opened up on us, but a running target was not too profitable at a range of three hundred yards. Even so, they got a few hits. By the time the enemy on the west had recovered and returned to the attack, I had the bulk of my outfit on the safe side of the wire. Aside from five severely wounded men who could not be carried along, the company reached the battalion position without further incident.

The battalion, with my company on the left, was established in the dense forest directly south of the three occupied French positions. The 1st Battalion was having trouble and was out of direct contact with our left, but by means of liaison squads we managed to keep in touch with their right. My company dug in some hun dred yards from the forest edge. Digging in the frozen ground was no fun.

So far the French artillery had devoted its entire attention to our old position and to the rear areas; and during the attack we had been spared its attention, probably due to poor infantry-artillery liaison. This had been remedied now, and we were subjected to a very heavy volume of retaliatory fire which interfered with our digging since the forward edge of the forest received particular attention. I prepared a complete report of the morning's action on a message form and attached a sketch of the Central and Labordaire positions.

Late in the afternoon of January 29th, following a heavy artillery preparation, the enemy counterattacked. Masses of fresh troops stormed through the underbrush, urged on by bugle calls and shouted commands, only to be met by our small-arms fire. They fell, sought cover, and returned our fire. Here and there a small group tried to work its way closer, but in vain! Our defensive fire smothered the attack with heavy losses, and large numbers of dead and wounded lay close to our lines. Under cover of darkness the French withdrew to the edge of the forest one hundred yards away and dug in.

The infantry fire died down, and we too began to dig, for our own trenches were only twenty inches deep. Before we could get much deeper, French artillery shells began dropping among us. These were steel-cased rounds of American design which were bursting all around and sending jagged steel fragments shrieking through the winter night to snap off good sized trees as if they were match-sticks.

Our positions offered inadequate cover for the harassing fire which, with few breaks, kept up all night. Wrapped in overcoats, shelter halves and blankets, we lay shivering in the shallow trench. I could hear the men jump as each new concentration hit near us. During the night we lost twelve men, which was a heavier loss than we had sustained during the entire attack. No rations could be brought up.

At dawn the hostile artillery activity slackened and we began to work on deepening our positions; but we were not allowed much time. At 0800 artillery fire forced us to quit, and the fire was followed by a strong infantry attack which we threw back with little difficulty. The same fate met succeeding attacks, and by afternoon our positions were deep enough so that we could stop worry ing about the effects of artillery fire. We had no communication trenches to the rear; so we had to wait until dark for our first hot meal.

Observations: The attack on January 29, 1915, showed the superiority of the German infantry. The attack of the 9th Company was no surprise, and it is difficult to understand why the French infantry lost its nerve and abandoned a well-prepared defensive position lavishly protected by wire, three lines deep, and well-studded with machine guns. The enemy knew the attack was coming and had tried to stop it by means of heavy interdiction fire. The fact that we were able to resort to offensive action and break from the encircled Labordaire position is ample proof of the combat capabilities of our troops.

It was unfortunate that neither the battalion nor the regiment was able to exploit the 9th Company's success. With three battalions in line, inadequate reserves were available. Shortages in small-arms ammunition and hand grenades increased our troubles in the defence of Labordaire. Several things happened simultaneously to render our situation most critical: First, the enemy seized the blockhouse on the extreme right; second, we received the battalion order to withdraw; third, we were short of ammunition; and, finally, our way back through the wire was swept by enemy fire. Any decision, other than the one made, would have resulted in terrific casualties if not total annihilation. Above all, it was impossible to wait for darkness; for the last round would have been fired well before 1100. Attacking the weaker enemy force on the east would not have paid dividends, for the more aggressive attack came from the west; and attacking to the east would have given the western force an excellent opportunity to strike us in the rear. Breaking off the fighting in Labordaire confirms the statement in the Field Service Regulations: “Breaking off combat is most easily accomplished after successful offensive manoeuvre. ”

In making our hasty preparations for the attack, we gave no thought to carrying heavy entrenching tools. The solidly frozen ground made our light tools almost useless. Even in the attack the spade is as important as the rifle.

Although there was a better field offire from the edge of the forest, the new position was one hundred yards inside the woods.

We had no intention of exposing the troops to a repeat performance of the Defuy woods bombardment, and still had a field of fire good enough to repel several French infantry attacks with heavy losses.

The losses from hostile artillery fire during the night of January 29-30 were so heavy because the troops did not dig in to a proper depth.

World History

World History