By the late 1850s the Province of Canada and the four Maritime colonies had already achieved self-government and arrived at a coherent sense of themselves, and were developing ambitions about a possible place in the world. It was uncertain where the boundary lay between the jurisdiction of the Colonial Office in London and those of the greedy, anxious, volatile colonial governments in St. John’s, Charlottetown, Halifax, Fredericton, and Toronto or Quebec City. What was certain was that colonial governments were developing a taste for more power. Nor did this appetite depend on size, but rather upon issues. Prince Edward Island was as vigorous in wanting jurisdiction over issues vital to its citizens as was the much larger and more powerful Province of Canada. Colonies were also beginning to write their own legislation, lightening old common-law rules about debt and debtors, dower rights, and the rights of women in general. There were colonial pressures to relieve women of common-law restrictions on control of movable property: that is, the money and securities that the common law had placed firmly under husbands’ control. As colonies grew in population, prosperity, railways, and trade, so too did their confidence, not to say cockiness, about themselves and their wish to do things in ways that seemed proper to them.

But having risen to be, say. Premier of New Brunswick or Nova Scotia, where did one go from there? Retire to the Bench? Some provincial premiers did. But when

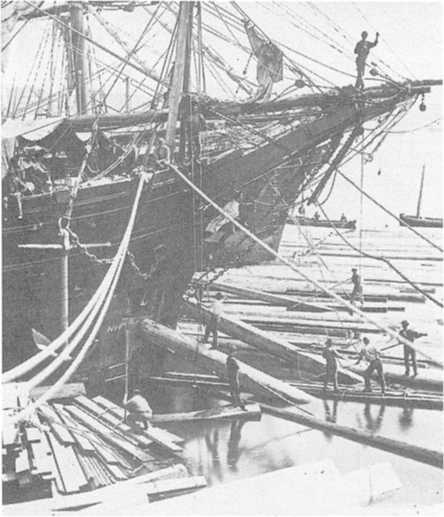

Loading a ship with squared-timber through the bow port, Quebec. The squared-timber trade in white pine had flourished during the Napoleonic years, but was beginning to decline by the time William Notman took this photograph in 1872.

Joseph Howe of Nova Scotia retired as defeated premier in 1853, he couldn’t do that; he wasn’t a lawyer. His successor, the Conservative Charles Tupper, couldn’t do it either; he was a doctor. Samuel Leonard Tilley, Premier of New Brunswick, was a Saint John druggist. The Bench, however honourable a resting place after political labours, was not an answer for talented men who had reached the upper limit of colonial public office. Francis Hincks, a premier of the Province of Canada, was a banker; he was appointed by the British in 1855 as Governor of Barbados, and later of British Guiana. But by the 1860s the British government had decided it could not go on making colonial governors out of defeated colonial politicians, whatever their merits. Joseph Howe would have liked to be one in 1863; instead he got employment in the Imperial Fisheries Protection Service. It was thin pickings. Politicians chafed at the restrictions and impediments to achievement in colonial society. So did the newspapers and the public.

The restlessness of colonial politicians was directly related to developing political ambitions. But politicians were not the only unsatisfied ones. Sir Edward Watkin of the Grand Trunk Railway began to think that new political agglomerations would stimulate railway building; so did Sir Hugh Allan of the Allan Line and the Montreal Telegraph Company.

The twenty years since the 1840s had been replete with changes not just in railways but also in steamships. The Royal William had been the first ship to cross the Atlantic under auxiliary steam, in 1833, from Quebec and Pictou, Nova Scotia, to Gravesend, with seven passengers and a load of Pictou coal. The person who ultimately benefited

This poster can be dated to between 1875 and 1878, while William Annand was Agent-General of Canada in London. (In 1879 Sir John A. Macdonald converted the post to Canadian High Commissioner.) Note the Allan Line steamer, square-rigged on the main and foremasts, fore-and-aft rigged on the mizzen, with steam auxiliary.

From that achievement was Samuel Cunard. He was born in Halifax in 1787, and had made some money in whaling, lumber, and coal, and he continued to reinvest his profits in shipping, warehouses, and the Halifax Banking Company, formed in 1825. Cunard grasped the central

Fact that the advent of auxiliary steam power in sailing ships meant that they could sail at least partly independent of wind or weather. Regularity, punctuality, speed, would not be achieved at once, for the sea was not so easily tamed; nor could human error be altogether avoided. Nevertheless, Cunard’s famous steamship line was a considerable success and certainly was to be his most enduring monument.

In 1839 Cunard submitted a bid to the British government to undertake a regular mail service from Liverpool to Halifax and Boston. He won a ten-year subsidy of ?55,000 a year; he continued to receive it after that partly because the Royal Navy liked his ships’ design and speed. His line began operations at the same time as Britain launched the new penny postage. On July 17, 1840, at 2 a. m., the first scheduled steam packet, the Britannia, arrived in Halifax, twelve days out of Liverpool. Note the time; at that hour a sailing ship might well have hove to and waited for dawn. The Britannia did not wait for anything; she discharged her passengers and mail, and set off for Boston, where she docked at 10 p. m. on July 19. By 1855 Cunard

Had converted his line to iron ships; by the early 1860s he had abandoned paddle wheels for screw propellers. When Cunard died in 1865 he left a considerable fortune. As one Nova Scotian wrote to a Halifax friend in 1866, “I miss our old friend Sir Samuel C—I think he has left ?600,000... a good large sum for him to have accumulated since the date that you and 1 remember him to have had little or nothing—so much for Steam in 20 years____” So much for steam, indeed!

The Allan Line is still more famous in the history of Canada. This Scottish-Canadian shipping line was founded in 1819. In 1854 the Allan consortium formed the Montreal Ocean Steamship Company, and in 1855 it too won an imperial mail contract. The Allan Line prospered, as had Cunard’s, by using innovative design and engineering. Allan ships became the mainstay of Canadian travel from the 1850s until the line was finally sold to Canadian Pacific in 1909. The Allan ships—the Canadian, the Indian, the Sarmatian, the Parisian, the ill-fated Hungarian, the Sardinian, the Buenos Ayrean (the first steel liner to sail the Atlantic), and many others—were known to Canadians for sixty years, sailing out of Montreal in summer, out of Portland, Maine, in winter. And Hugh Allan’s enterprise went much further than that; he launched into railways, banking, insurance, and manufacturing. In 1864 he founded the Merchants’ Bank in Montreal; it was soon one of the most aggressive Canadian banks. Allan was the quintessential Montreal financier, and his great success helped to establish Montreal, from 1860 onward, as the financial capital of Canada.

Shipping and government worked together. The success of the Allan Line was made possible by the Canadian government’s deepening of the main St. Lawrence channel through Lake St. Peter to sixteen feet in 1853. The government also made it a point to subsidize the erection and maintenance of certain lighthouses on the approaches to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the most important of which was at Cape Race on the southern tip of Newfoundland.

Within twenty-five years of the first transatlantic steamship lines came the transatlantic cable. Telegraph companies had appeared in Canada within two years of Samuel Morse’s first successful telegraph line between Washington and Baltimore in 1844; in 1847 Hugh Allan had founded the Montreal Telegraph Company, which soon connected Montreal with Portland, Toronto, and Detroit. The Atlantic cable was the natural outgrowth of shipping and the telegraph. The first cable was laid down on the sea-bed in 1858, from Ireland to Trinity Bay, Newfoundland. Queen Victoria used it to send a message to President James Buchanan before it ceased functioning owing to sea-water leaking through the insulation. A second cable was laid

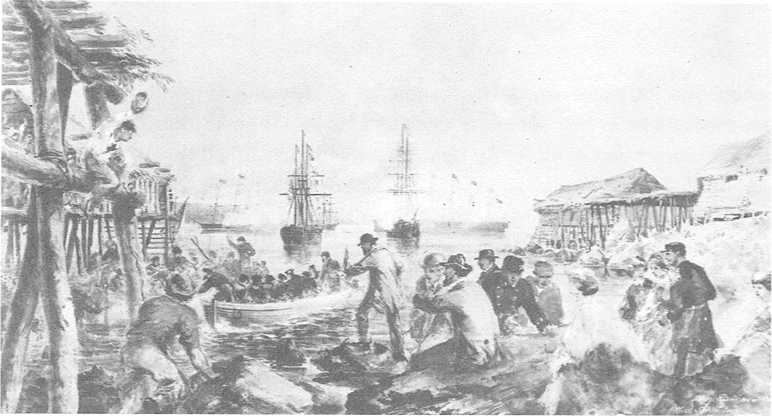

Heart’s Content, Newfoundland: Arrival of Transatlantic Cable, 1866. The first attempt at a transatlantic cable was a failure because water penetrated the insulation. But in July 1866 the Great Eastern, the largest steamship then afloat, landed the western end of a cable at Heart’s Content, in Trinity Bay, Newfoundland; the eastern end was at Valentia, at the south-west corner of Ireland. Watercolour (1866) by Robert Dudley.

By a monster of a new iron ship, the Great Eastern, and was brought ashore at Heart’s Content, Newfoundland, in July 1866. The transatlantic cable and steamships, like the railways, were symbols of how the world was being brought closer to Canadian shores, how distances were shrinking before the power of technology.

This marvellous new web of telegraph cables, transportation improvements, and innovations in ship design lay behind the political drive towards Confederation. British North American politicians were fully aware of these new techniques and used them; they travelled on Hugh Allan’s and Cunard’s ships, they banked at the Merchants’ Bank, they used Allan’s telegraphs. The Confederation movement was backed to the hilt by the Montreal business community, although quietly and behind the scenes. The Montreal Gazette, the business community’s most characteristic spokesman, was enthusiastic about the new movement for Confederation—the union of all the British North American colonies.

The experience generated by new inventions, new technology, created expansionist political and social ideas. Not everyone shared such ideas, but anyone who read newspapers had to be aware that the world was changing rapidly. It was not surprising that as early as 1851 Joseph Howe spoke of the day when his younger listeners

Would hear the steam whistle of a locomotive in the passes of the Rocky Mountains. He tried and failed that same year to get them to hear it in the Cobequid Hills, to get the governments of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Canada, and Great Britain to agree to build the Intercolonial Railway from Halifax to Montreal. Given this failure, he cannot be blamed for thinking that the sea that lay at Nova Scotia’s gates was an opportunity more inviting than the 1,000 kilometres (600 miles) of woods between Halifax and Montreal, and therefore basing his “federation of the empire” upon the technology of the steamship.

World History

World History