The Romans were master builders who, while they only developed a few new building technologies, used those that were already available to their fullest potential and produced many structures that have remained standing for thousands of years.

In the early stages of Roman history, buildings would have been simple constructs of timber, mud, thatch, and stones. A number of deposits of good clay located in or near Rome were exploited for making mud bricks. The clay was combined with a tempering agent such as grass or straw and then formed into bricks, which were exposed to the sun to dry. The ideal drying time for such bricks was as long as several years, but many were probably used sooner than that. Although such bricks were vulnerable to water, they were nonetheless one of the standard components of republican buildings. The same clay was also shaped into tiles, then fired in an oven to render them waterproof, and thus were employed as a common roofing material.

It was not until around the last century of the republic that the Romans seem to have begun firing the bricks used in construction. These bricks were formed by packing wooden molds with a mixture of clay, sand, and water and then either placing them in a kiln to harden or firing a whole stack of bricks. Bricks most commonly resembled low, flat squares or rectangles and seem to have been made in a number of standard sizes. The manufacturers frequently stamped bricks with their names or other information. Particularly during the high empire, these stamps sometimes included a wide range of data useful to archaeologists and historians such

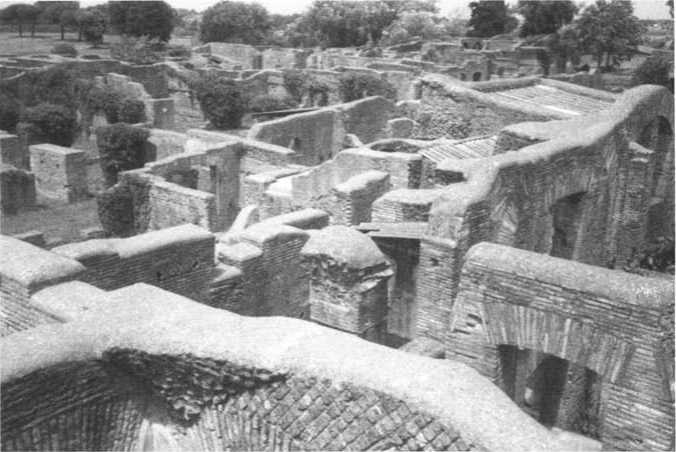

Figure Appendix IV. l View of ruins in Ostia showing brick-faced construction technique.

As the name of the landowner where the clay was gathered, the name of the manufacturer, the site of manufacture, the distributor, the current consuls, and even the construction project for which they were intended.

One of the truly brilliant innovations of the Romans was their development of a useable form of concrete. Lime mortars had been used from at least the third century bc, but by the time of Augustus, a highly flexible type of concrete had been discovered. Roman mortar was created by mixing lime with aggregates and water. The lime had to be properly burned, and the proportions of different materials had to be accurate or else the end result would not set properly and would be prone to cracking.

When one thinks of Roman monumental public architecture, one often envisions structures of shining marble, but this was usually only the exterior surface. The structural core of these buildings was usually composed of much more humble materials such as rubble fill, brick, and concrete. Typically, a core of concrete and aggregates would be poured, and then the surface would be dressed in one of several possible ways. When faced with an irregular outer layer of small stones, the style was called opus incertum; with square stones, it was called opus reHculatum; and with brick, it was known as opus testnceum. Concrete could also be poured in a variety of forms using wooden molds, so this opened up new possibilities of architecture since structures could be made in many shapes, including ones with curves and irregularities. The Romans even invented a special type of concrete using pozzolana, a volcanic stone, that would harden under water. This was used to build gigantic harbors and breakwaters to protect the ships. The concrete revolution was a very important part of Roman architecture since buildings would have a core of concrete, which was then covered up by a layer of marble or brick depending on how fancy or expensive a building it was.

While the exteriors of major public buildings such as temples or theaters were covered with sheets of fine decorative stone such as marble, the floors, columns, carvings, and other ornamental elements were also fashioned out of such materials. These decorative stones were imported at an enormous expense from quarries all around the Mediterranean. Some of the main varieties of stone imported included fine, white marble from mines in Carrara in Italy, Mount Pentelikon near Athens in Greece, and the island of Paros in the Aegean. Green cippoUino arrived from Carystos in Greece, and yellow - and purple-veined pavonazzetto from the Docimion quarries in Asia Minor. From Egypt came hard purple and green porphyry that had been hauled across the desert, as was grey granite from the Egyptian mines at Mons Claudianus.

A second Roman innovation was widespread use of the vault. A series of stones was cut so that, when put together, they created a curved arch. This form was self-supporting since the stones' own weight held them together. Architects soon realized that if they put two vaults together meeting at right angles, they would create a roof that could span huge rooms without the need for columns.

There was a wide variation in the quality of Roman buildings. The insulae, or high-rise apartment buildings, in which the majority of the inhabitants of Rome lived, were often poorly made, using inferior materials, shoddy workmanship, and insufficient structural supports. The predictable result was that they often crumbled or collapsed. The Romans also tended to make widespread use of plaster as a final layer over walls, and this finishing technique was sometimes exploited to cover up poor-quality construction. Even in the houses of the wealthy at Pompeii, a layer of plaster often conceals a myriad of flaws. On the other hand, most of the monumental public buildings erected by the Romans seem to have been made with great solidity that rendered them immune to disasters such as floods as well as to centuries of plundering and neglect. The continued existence today of such monuments as the Pantheon is an impressive testimony to the soundness and longevity of high-quality Roman construction and engineering.

World History

World History