The Proto-urban phase was followed by a phase from the mid-fourteenth century BC through to the end of the Bronze Age in ca. 1100 BC (LC IIC-IIIA periods) that witnessed the (re)construction, urbanization, and monumentalization of a number of settlements. Although we can bring evidence to bear from a larger number of sites to discuss this, it is important to emphasize that the following account is sTill based on limited and discontinuous exposures. Enkomi is the exception with nearly 20 percent of the known area of the site from this phase excavated (Figure 6.2), but there are various unresolved issues regarding the site's stratigraphic sequence that limit its use in understanding some aspects of LC urbanism (see Fisher 2007:120-122 for a summary). In any case, if excavations at sites such as Enkomi and Kalavasos-A;yios Dhimitrios are any indication (and

To this we can add glimpses from Alassa, Hala Sultan Tekke, Kition, EpiskopI (Kourion)-Bamboula, and Pyla-Kokkinokremos), the construction of many of the new cities involved the architectural definition and enclosure of the majority of space within the urban areas through the contiguous placement of building walls and streets (Astrom 1996; Courtois et al. 1986:5-8, figure 1; Hadjisavvas 1986; Karageorghis and Demas 1984, 1985; Weinberg 1983; Wright 1992:115). We can begin by examining this at the spatial scale of the city as a whole - the urban landscape - and attempts by ruling elites to impose order on it.

MAKING THE FIRST CITIES ON CYPRUS

The PlanneD City: Elite Place-Making Writ Large

One of the most striking features of many LC cities is the extensive use of urban planning, often characterized by particular street arrangements, which determined the position and alignment of most of their constituent buildings. This is seen most clearly at Enkomi, which, after a major destruction ca. 1200 BC, was rebuilt in an impressive manner exhibiting a number of the hallmarks of centralized planning recently discussed by Michael Smith (2007). These include formality and a coordinated arrangement of buIldings and spaces combined through the use of a modular orthogonal plan (Figure 6.2). The grid, oriented to about 7 degrees west of north, consists of a single, central north-south artery dissected by nine evenly spaced, east-west running streets, forming twenty blocks. The fact that the outer walls of the Ashlar Building follow the boundaries of an underlying building from the previous phase might suggest that at least some elements of this layout were already in place before the city's reconstruction (see Dikaios 1969-1971:plates 292-293; Wright 1992). This was demarcated by a "cyclopean" fortification wall (i. e., made with a base of massive roughly shaped boulders) with towers that enclosed an area of about 14 ha (Courtois et al. 1986:5-8, figure 1). A ring road appears to have run around the inside of the fortiica-tions. The plan also exhibits monumentality in the construction of a number of monumental buildings built partially or wholly of ashlar masonry, some of the most impressive of which (Building 18 [which is actually a series of elite residential units] anD the Ashlar Building) are found along the city's central axes. The existence or nature of any settlement outside the walls is unknown (lacovou 2007:10).

The failure of the published plans from the French excavations (e. g., Schaeffer 1971:plan IV) to distinguish among walls of various

Phases makes it difficult to ascertain the precise boundaries and internal structure of many of Enkomi's individual buIldings. The centrally located Ashlar Building (Dikaios 1969-1971:171-190; Fisher 2007:Ch. 6) is substantially larger than any other structure, but it appears to have been an elite residence and lacks compelling evidence for administrative activities. The lack of a single obvious administrative center and the generally widespread distribution of the highest status goods among elite graves throughout the city has led Keswani (1996; 2004:115) to suggest that there was no single focus of administrative power at Enkomi and that the site was therefore characterized by a heterarchical sociopoLitical organization with power dispersed among multiple nodes (also Manning 1998:53; see Magnoni et al., Chapter 5 Of this volume for a similar situation at the Classic Maya site oF Chunchucmil).

The city of Kalavasos-A;yios Dhimitrios, dating mainly to the LC IIC period (ca. 1340/15-1200 BC), represents a somewhat different spatial configuration. Excavations in several areas of this site reveal various buildings and roads that are generally oriented to 25 degrees west of north, indicating that the city was laid out on a preconceived plan (South 1980, 1995; Figure 6.3). No fortification wall has yet been found, but the distribution-of-surface finds and architectural remains suggest that the site was about 11.5 ha in size. The plan consists of at least one major "north-south" street and one or more transverse "east-west" streets (Wright 1992:115).2 The main north-south street, roughly 3.8 m wide, appears to extend at least 150 m through three separate excavation areas. Not enough of the urban fabric has been recovered to determine whether the plan is a modular orthogonal grid such as at Enkomi, or a simpler integrated orthogonal plan in which the buildings are aligned to one or more large-scale features (see Smith 2007:12-21). Some form of zoning may have been imposed in which the monumental administrative buildings were in the northeast, whereas higher-status residences, some of which also contained industrial facilities, were found in the eastern and central parts of the city, and smaller, and nonelite dwellings were on the western outskirts (Wright 1992:115). The latter are on a slightly different alignment (closer to north) than the rest of the city's buildings and infrastructure. Elsewhere, the plan exhibits symmetry and conformity, seen in the alignment of buildings on opposite sides of the street and the possible existence of "lots" demarcated by long stretches of wall (South 1995:192).

Figure 6.3 Schematic plan of Kalavasos-Ayios Dhimitrios (drawn by author based on topographic data provided by Alison South).

South (1988:223) has argued that a large wall excavated along the north and east side of the Northeast Area may have enclosed this part of the site, which contained monumental structures, including Building X - the largest and most architecturally elaborate building

Figure 6.4 Detail of Northeast, Central and East excavation areas at Kalavasos-Ayios Dhimitrios, including results of ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey (see Fisher et al. 2011-2012 for details; adapted by author from plan provided by Alison South).

Yet found at the site and likely its administrative focus. A recent survey by the Kalavasos and Maroni Built Environments (KAMBE) Project using archaeological geophysics appears to supporT this contention, suggesting an arrangement of structures delineating the southern limit of the Northeast Area (Fisher et al. 2011-2012; Figure 6.4). Where these features intersect with the main north-south road, there appears to be a structure that narrowed the roadway, possibly indicating an attempt to control physical and visual access to this area of the city, yet another hallmark of centralized planning (Smith 2007:23-25). The presence of this single and separate

Administrative area implies a hierarchical organization of power at Kalavasos-A;yios Dhimitrios, with a paramount ruling individual or group (Keswani 1996).

MAKING THE FIRST CITIES ON CYPRUS

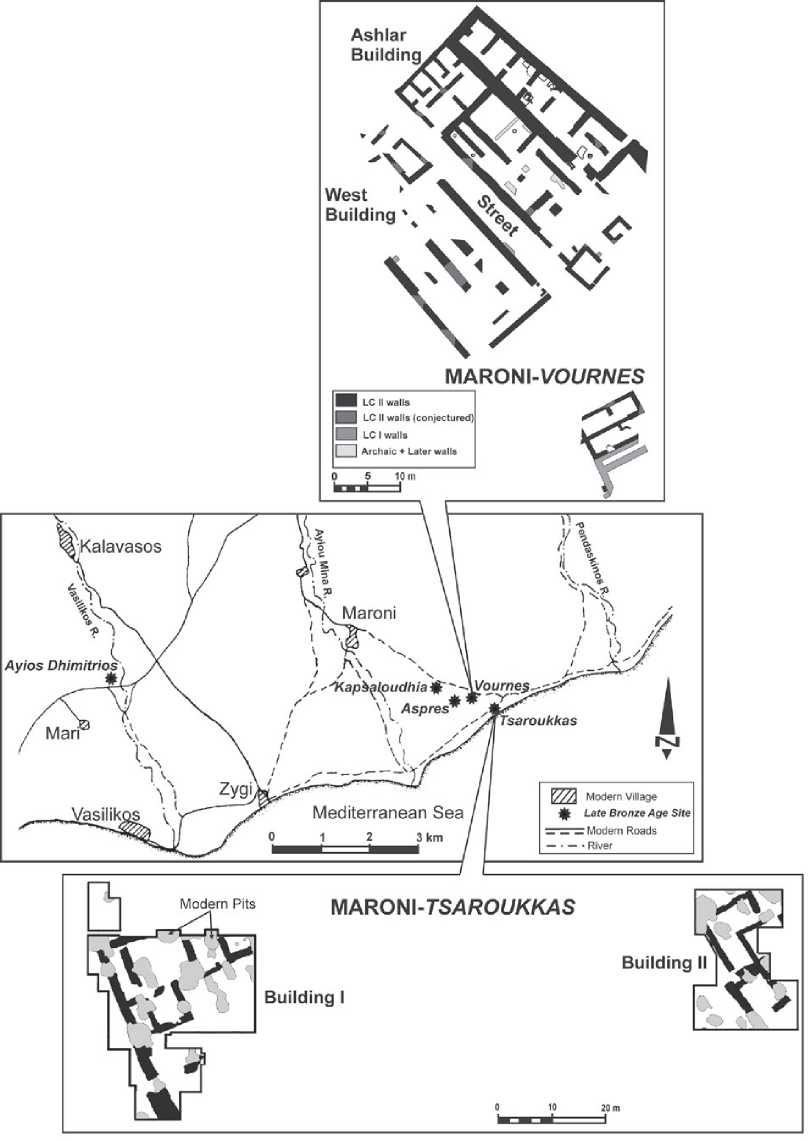

The urban centers of Maroni anD Alassa likewise had monumental zones that appear to have been the primary focus of elite power at each site, although it is unclear how they articulated with nearby settlement areas. A survey in the Maroni Valley suggests a fairly continuous 15-25 ha area of LC occupation down to the shoreline, although it is presently unclear whether remains of buildings and tombs found at Vournes, Aspres, Kapsaloudhia and Tsaroukkas represent continuous or dispersed urban development (Fisher et al. 20112012; Manning 1998:42; Manning et al. 1994; Manning and Conwell 1992; Manning and De Mita 1997; cf. lacovou 2007:7; Figure 6.5). Excavations of an elevated zone at Maroni-Vournes revealed a monumental building complex dating to Late Cypriot IIC that included the Ashlar Building, a 30.5 x 21 m structure built in part with ashlar masonry and separated from an adjacent storage building by a 4.5 m wide street (Cadogan 1984, 1992). A few small sterile trenches to the east of Vournes led Cadogan (1984:2) to conclude that it was physically separated from contemporaneous utilitarian buildings and tombs found at the coastal site of Maroni-Tsaroukkas, nearly 500 m to the southeast. These buildings are on a different alignment (ca. 25 degrees west of north) than those at Vournes (ca. 45 degrees west of north). Ongoing geophysical survey and test excavations by the KAMBE Project at Maroni between Vournes and Tsaroukkas (Fisher et al. 2010-2011) have revealed the remains of contemporary LBA structures interspersed with open spaces, suggesting a lower-density or less-integrated form of urbanism than seen at sites such as Kalavasos or Enkomi.

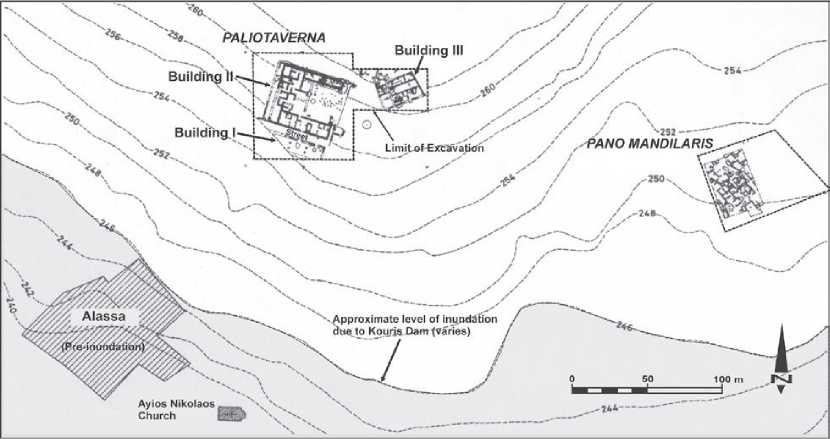

Like Maroni, Alassa-Paliotaverna is characterized by the presence of monumental structures dating to the LC IIC-IIIA, including Building II, a massive court-centered building (37.7 m per side) built almost entirely of elaborate ashlar masonry (see Hadjisavvas 1986; 1996). To the south, across a 4.3 m wide street, was a large, pillared hall, also built of ashlar masonry (Building I). Paliotaverna appears to have been separated from an area of nonelite domestic architecture found downslope at Alassa-Pano Mandilaris, nearly 200 m to the east and built on a different alignment (Figure 6.6).

The coordinated arrangement of buildings and spaces seen within the monumental areas of both Maroni and Alassa is indicative

Figure 6.5 Map of the Maroni region with schematic plans of excavation areas at Vournes and Tsaroukkas (adapted by author from Manning i998:figure 2; Fisher 2007:figure 7.24; Fisher et al. 20ii-20i2:figure 9).

Figure 6.6 Map of the site of Alassa, showing the Paliotaverna and Pano Mandilaris localities (adapted by author from map by A. Kattos in Hadjisavvas 2003:figure 2).

Of centralized planning, even if these areas were not tied to nearby domestic areas through an orthogonal grid. Similarly, one could perhaps see areas of domestic architecture at both Hala Sultan Tekke and Pyla-Kokkinokremos, in which several adjoined houses were aligned on the same orientation, as the result of higher-level planning (Astrom 1989; Karageorghis and Demas 1984; Figures 6.7 and 6.8). As Smith (2007:14-16) points out, however, this sort of pattern could potentially arise from the actions of individual builders who made additions or new structures next to existing ones based on factors of practicality, efficiency, or, in the case of Pyla, the presence of the plateau edge. Astrom (1996:10) claims that Hala Sultan Tekke had an orthogonal town plan with streets at right angles (he uses the term "Hippodamic"), but it is difficult to substantiate this on the basis oF the published plans (e. g., Astrom 1989:fgure 2; Figure 6.7).

Based on the available evidence, it appears that there was no ideal plan for a Late Bronze Age city on Cyprus and that each was a product of individual site histories and trajectories of urban development (lacovou 2007). The urban landscape of Maroni, and perhaps the still poorly understood LBA occupation of Palaepaphos (lacovou 2007:3-6), may represent lower-density forms of urbanism than those materialized in the more integrated or nucleated plans of cities such as Enkomi and Kalavasos. In many cases, these cities share spatial configurations in which physical and social boundaries

KEVIN D. FISHER

Figure 6.7 Hala Sultan Tekke, schematic plan of excavation Areas 8 and 22 (adapted by author from Astrom I989:figure 2).

Were increasingly defined through the construction of buildings and street systems. For the most part, open spaces - the control of which had likely been negotiated among competing groups through the placement of tombs in the Proto-urban phase (again, based mainly on limited exposures from Enkomi) - were now incorporated within the structure of contiguously placed buildings on well-defined streets. This is quite clear in Area I at Enkomi, where a succession of Proto-urban buildings centered around multiple courtyards that were open on one side was replaced by the fully enclosed LC IIIA Ashlar Building (Dikaios 1969-1971:153-190). Here, the function of the tombs as territorial markers was preserved in the LC IIIA street pattern on the north and south of the new Ashlar Building. In some cases, earlier elite tombs continued to be used in the new urban environments, marking an attempt to demonstrate real or ictive continuity of ownership and power (e. g., Tomb 13 and its newly built subsidiary Tomb 12 in the street west of Building X at Kalavasos-Ayios Dhimitrios; South 1995:72). In other cases, as at Maroni-Vournes (Manning 1998), new elites marked their ascendancy over the

Figure 6.8 Pyla-Kokkinokremos, schematic plan of Complexes A-E (adapted by author from Karageorghis and Demas i984:plan i).

Previous sociopolitical order by constructing their new buildings directly on top oF the earlier tombs.

I would argue that the overall plans (streets, fortifications, and monumental buildings) of the new cities were products of top-down decision making by ruling elites, whether they exercised political power locally or at some wider regional or island-wide level. As Kostof (1991:33) argues in The Cit-y Shaped, "[c]ities, even those attributed to spontaneous processes inherent in a region, are never entirely processual events: at some level, city making always entails an act of will on the part of a leader or collectivity." Indeed, the general form of the new urban environments was a product of elite place-making writ large, symbolized at some sites by the use of the grid, which has been recognized as a tool of dominance and oppression in societies engaged in centralizing authority (e. g., Grant 2001; Love 1999). A close association exists between the constitution of authority of political regimes and the form and aesthetic of urban political landscapes (A. Smith 2003). In a similar vein, Foucault (1977) has demonstrated how the configuration of space contributes to the maintenance of power of one group over another through the control and surveillance of the movement oF bodies through space.

In addition, other than the streets, there is a notable lack of large, open, publically accessible spaces that couLd be used for spontaneous gatherings or planned public-inclusive social occasions among a city's inhabitants and visitors. This could be seen as an attempt by those who planned the city's infrastructure to limit the occurrence of large-scale, uncontrolled social gatherings. A number of studies have founD that open public spaces stimulate political action, civic engagement, and democratic practices (Shin 2009:426). Monica Smith (2008) argues that open spaces provide flexible venues for planned and unplanned performances and the opportunity for consensus building in dense populations. The central square at Enkomi (see Figure 6.2), located at the city's main crossroads (the North-South Artery and Street 5), was one of few such spaces and likely an important venue for both informal gatherings and public-inclusive social occasions. Given its capacity (as many as 380 standing persons based on modern architectural conventions [see Fisher 2009a:444], not including the adjoining road space), such a place had the potential to serve as a prime context for interactions aimed at resisting or undermining the social order represented by the nearby monumental buildings and the overall urban plan.

Other large, open spaces tended to be more carefully controlled. For example, I previously noted that the main north-south road at Kalavasos-Ayios Dhimitrios may have reached some form of intervening structure as it approached the Northeast Area (see Figure 6.4). Beyond this point, the road widens to 6 m, creating a large space more than 30 m long that may have functioned as the terminus of a processional or ceremonial way or similar performative space. Here, earlier elite tombs (Tombs 12, 13, 14, and 15) would have been visible in the street, their entrances marked with vertically placed stones and possibly posts (South 1997:170). The street was bounded on the east by the poorly preserved ashlar facade of Building XII, and ended at the southwest corner of Building X. This was Building X's most impressive facade, made with a plinth of monumental ashlar blocks wIth drafted margins and lifting bosses, topped by an orthostat of large blocks, also with drafted margins. The space deined by these facades undoubtedly provided an imposing context for social occasions that took place here, including the arrival or departure of Building X's elite inhabitants, as well as the arrival of visitors who were permitted access to this part of the city, perhaps as participants in the feasting events that occasionally took place within Buildings X and XII (see Fisher 2009b; South 2008).

The cities of the fully urban phase of the LBA were the ultimate expressions of the desire to control movement and interaction, first seen in the Proto-urban forts. Their extant remains indicate the large-scale appropriation of space and its incorporation into planned, imageable built environments. Kevin Lynch (1960:9) sees imageability as "that quality in a physical object which gives it a high probability of evoking a strong image in any given observer. It is that shape, color, or arrangement which facilitates the making of vividly identified, powerfully structured, highly useful mental images of the environment." The enclosure of some urban environments (e. g., Enkomi anD Kition) by massive cyclopean fortifications undoubtedly contributed to this imageability, while providing ruling elites additional means to control movement and participation in particular social interactions. In addition to their military and defensive functions, these walls vividly materialized the boundaries of the city proper and those who lived within them may have increasingly identified themselves in terms of a built-up, complex, ordered, and perhaps cosmopolitan cityscape that stood in contrast to the rural lands beyond - regardless of the failure of such an ideal to reflect the socioeconomic reality of city-hinterland interdependence.

MAKING THE FIRST CITIES ON CYPRUS

The highly imageable urban center was likely one the more clearly defined places with which many Late Cypriot people identified. Indeed, Cowgill's definition of a city outlined earlier emphasizes the formation of a distinct urban identity through daily practice. Environmental psychologists have long noteD the important role of place attachment at various scales in the formation of self - and group identities (Fisher and Creekmore, Chapter 1 of this volume; Proshansky 1978; Proshansky et al. 1983; Twigger-Ross and Uzzell 1996). Proshansky (1978:161) argues that an urban identity arises from the physical characteristics and requirements of life in urban contexts that socialize individuals to move, think, feel, play social roles, and solve problems in ways that are uniquely urban. Therefore, the experience of living in urban environments (i. e., an urban lifestyle) or, in some cases, attachment to particular cities, can form the basis of urban identities (Feldman 1990; Graumann 2002:109-110; Lalli 1992; Magnoni et al., Chapter 5 Of this volume; Proshansky et al. 1983:78). This sort of place identity also developed through more localized forms of place-making that resulted in the production of (and attachment to) neighborhoods anD households.

Between City and Household: Late Cypriot Neighborhoods

Urban communities that were intermediate between the city and the household undoubtedly existed in LC cities, although defining their social and material boundaries is no simple matter. Michael Smith (2010) recently argued that the division of cities into neighborhoods and districts was a universal of urban life for all time periods. He defines a neighborhood as a residential zone that exhibits a great deal of face-to-face interaction and is distinctive on the basis of physical and/or social characteristics, while a district is a larger administrative unit within a city (Smith 2010:139-140). Distinct districts are difficult to substantiate in LC urban centers, given their relatively small size and limited exposures, but we are perhaps better able to identify neighborhoods. In modern urban settings, neighborhoods have long been acknowledged as an important level of social organization (recently, Garrioch and Peel 2006). They become political and social communities, providing a frame of reference for the individual and a venue for the exchange of skills, emergency assistance, and mutual protection (Hallman 1984:11; M. L. Smith 2003:20-21). Neighborhoods have also been noted as being particularly important in the formation of individual and group identities and place attachment (often referred to as "neighborhood attachment") among their residents (Brown et al. 2003; Comstock et al. 2010). Although mostly absent from discussions of LC cities (cf. Weinberg 1983), neighborhoods have been recognized in other ancient contexts, including Mesoamerica (e. g., Arnauld et al. 2012) and Mesopotamia (e. g., Creekmore 2008, Chapter 2 of this volume; Nishimura, Chapter 3 Of this volume; Stone 1996; cf. van de Mieroop 1992). Textual sources from Mesopotamian cities of the Old Babylonian period indicate that neighborhood associations actively mediated between households and the city-level bureaucracy (Keith 2003). In Mesoamarica, Cowgill (1992) has suggested the existence of neighborhoods based on ethnic groups aT Teotihuacan.

An early form of neighborhood on Cyprus migHt be traced back to the founding of Proto-urban Enkomi and Morphou-Toumba tou Skourou in the seventeenth century BC. Keswani (1996) argues that these sites were initially formed by residents of other communities and even other regions, who gathered in localities well suited to exploiting foreign trade. The dispersed arrangement of compounds at early Enkomi and the residential and industrial zones associated

With multiple mounds attested at Toumba tou Skourou (Vermeule and Wolsky 1990) might reflect the existence of nascent neighborhoods rooted in these heterogeneous origins. This contrasts with fully urban Enkomi during the LC IIIA (ca. 1200 BC), which was arranged in clearly deined blocks by the street system previously discussed (see Figure 6.2). Although the internal arrangements of most of these blocks are unclear owing to the conflation of various architectural phases in published plans (e. g., Courtois et al. 1986:igure 1), it appears that each consisted of a number of contiguously placed buildings of various shapes and sizes. Several blocks (especially blocks 4E, 5E, 5W, and 6E) exhibit a fairly regular wall line bisecting them along their east-west axes, perhaps further evidence of higher-level planning through the use of regular lot depths. While it is possible that these blocks might have constituted some form of neighborhood, residents would likely have had greater occasion to interact with those who lived in units across the main streets. This socio-spatial arrangement is referred to as a "face-block" neighborhood, deined as two sides of one street between intersecting streets (Suttles 1972; American Planning Association 2006:409). Distinctive features, such as the ashlar facade pierced with unique windows that ran along the north side of Street 5 West (i. e., the south wall of Building 18), gave some of these face-blocks high imageability.

MAKING THE FIRST CITIES ON CYPRUS

Karageorghis anD Demas (1988:58) appear to be referring to a neighborhood when they suggest that Buildings II and IV at Maa-Palaeokastro combined with Areas 96 and 99 and Rooms 73, 76, and 77 to form an "architectural grouping" that might have represented a level of integration between individual households anD the wider settlement (Figure 6.9). In other cities, there were areas deined by the concentration of particular building types that might also be seen as neighborhoods. The administrative areas of Kalavasos (the Northeast Area), MaronI (the Vournes locality), and Alassa (the Paliotaverna locality) discussed earlier, with their monumental ashlar buildings and evidence for production and storage, or Area II at Kition where ive temples connected by courtyards and workshops were recovered (Karageorghis and Demas 1985; cf. J. Smith 2009), were all distinct in this way. But, these areas were not primarily residential and many social interactions would have been limited to particular times of day or other activity cycles.

At Kalavasos-Ayios Dhimitrios, the area of what Wright (1992:115) describes as "poorer" dwellings in the western-most part of the site

KEVIN D. FISHER

Figure 6.9 Schematic plan of Maa-Palaeokastro, Area III (adapted by author from Karageo-rghis and Demas 1988:figure 15).

Might be an example of a neighborhood based on socioeconomic status (see Figure 6.3). As noted previously, the buildings (likely houses) in this part of the site are on a slightly different alignment (closer to north) than the rest of the site's architecture and appear to have significant spaces between the buildings, in contrast to the contiguous and more ordered construction seen along the main north-south road. It is important to bear in mind that this part of the site was incompletely excavated and that any conclusions regarding the status of its inhabitants are based mainly on the generally smaller size of these buildings and the lower quality of their extant masonry compared wIth houses recovered to the east (South 1980:42). A similar dynamic may have existed at Episkopi-Bamboula, where Area E has generally larger houses, which were arranged in orderly blocks delimited by streets, in contrast with the smaller and more organically arranged dwellings of Area A (Weinberg 1983:52-57, figures 18-20). This could represent a form of zoning as part of the overall urban plan. Such practices have sociopoLitical implications as authority (legally based or otherwise) is employed to control social relations through the segregation or exclusion of certain groups (Madanipour 1998; Shin 2009:431). In modern cities, spatial and residential segregation is

Known to create social enclaves and categorical relationships by limiting social interaction within racially, socioeconomically, and culturally homogeneous social groups, raising the potential for conflict and tension among segregated groups (Shin 2009:434).

MAKING THE FIRST CITIES ON CYPRUS

The use of shared facilities could have been an additional basis for the kind of face-to-face interactions that deined particular neighborhoods (Keith 2003). For example, in spite of Bolger's (2003:49) contention that the water supply became increasingly privatized in LBA Cyprus, dwellings from a number of sites have no evidence for their own permanent water extraction or collection facilities, such as wells or cisterns. This suggests that many, if not most, households would have used communal water facilities, such as the large, well-built well found in Area B at Episkopi-Bamboula. This feature was 1.8 m square, aligned to the cardinal points, and does not appear to have been encloseD by any architecture (Weinberg 1983:32, plate 8). At Hala Sultan Tekke, even though Buildings A, C, and D had their own wells, the well (F 1620) located in Room 59 was located at the end of what Astrom (1998:54-8) describes as a raised, communal passageway accessed by a street that ran along the northern edge of Building C (Figure 6.7). In addition, Karageorghis and Demas (1988:61) suggest that Buildings II anD IV at Maa - Palaeokastro may have shared communal food preparation facilities in Area 96, Room 76, and possibly Area 99 (Figure 6.9).

Urban Households: Place-Making from the Bottom-up

It is clear that there were likely several overlapping bases around which neighborhoods might have formed, but each would have consisted of a number of individual households. Like neighborhood, household is a concept with interwoven material-spatial and social components. It is traditionally seen as a minimal social unit that meets certain basic needs of its members (economic, social, and biological) and is generally distinguished from family by co-residence, or at least locality, rather than kinship (Bender 1967; Rogers 1995; Santley and Hirth 1993; Yanagisako 1979). Current approaches instead emphasize the social interactions within and between households, seeing them not as functional units, but rather as a set of social relations enacted through practice (Hendon 2004; Meskell 1998). As Wilk and Rathje (1982:618) famously stated, archaeologists do not dig up households, but must infer them from the material record of houses and their

Associated artifacts. The house can act as a medium through which the wider community can exercise a measure of control over what goes on within, yet it also provides a means of separating the actions of household members from that wider community (Allison 1999:1; Ardener 1993:11; also Altman and Gauvain 1981:287). The design of domestic space interacts with human action and meaning to create places "in which the house becomes integral to the construction of social identities through a process of. . . movements, views and spatial arrangements" (Hendon 2004:276).

Individual houses have been identified in all of the major LC urban centers. Unfortunately, individual urban buildings have often been distinguished in binary terms of "private" domestic architecture and "public" monumental architecture, in spite of the fact that both building types contained spaces that were, to varying degrees, public and private (domestic). Whatever administrative, economic, and ideological functions they may have had (and in spite of their size and architectural elaboration), most monumental buildings were, in fact, dwellings for elite households, likely including a number of retainers. I have presented detailed arguments elsewhere regarding the vital roles thaT the monumental buildings and new types of nonelite housing both played in LC sociopolitical dynamics (Fisher 2007, 2009b, 2014). These new types of urban buildings and their constituent spaces provided the contexts for much of daily practice as well as occasional social interactions (such as feasts) that brought various individuals and groups together as social identities, roles, and statuses were negotiated, established, and displayed. Here I will briefly consider how these individual buildings and the households who lived in them were woven into the wider urban fabric.

In spite of the perception of LC settlement plans consisting of independent freestanding structures (e. g., Bolger 2003:49), most of the buildings from the fully urban period show, rather, an agglom-erative (albeit ordered) arrangement in which they were constructed side by side and often shared outer walls. It was necessary for residents of such built environments, where nearly all space was architecturally defined, to demarcate and maintain the boundaries of the area under their direct control as unambiguously as possible. These boundaries defined what Altman (1975:111-120) refers to as househoLd members' primary territory - spaces used by them on a relatively permanent basis and central to their day-to-day lives. Such spaces tend to have markers more closely reflective of the personal

Qualities and central values of the occupants (Brown 1987). They also reflect an increased concern for privacy during the LBA and Bolger's (2003:49) contention that this period witnessed greater privatization of domestic activities is borne out in the limited physical and visual accessibility oF LBA houses from the outside (Fisher 2014). Given the relationship between power and knowledge through surveillance (Foucault 1977), this might be seen on one level as an act of resistance against the power structures that came to intervene in various aspects of LBA life.

MAKING THE FIRST CITIES ON CYPRUS

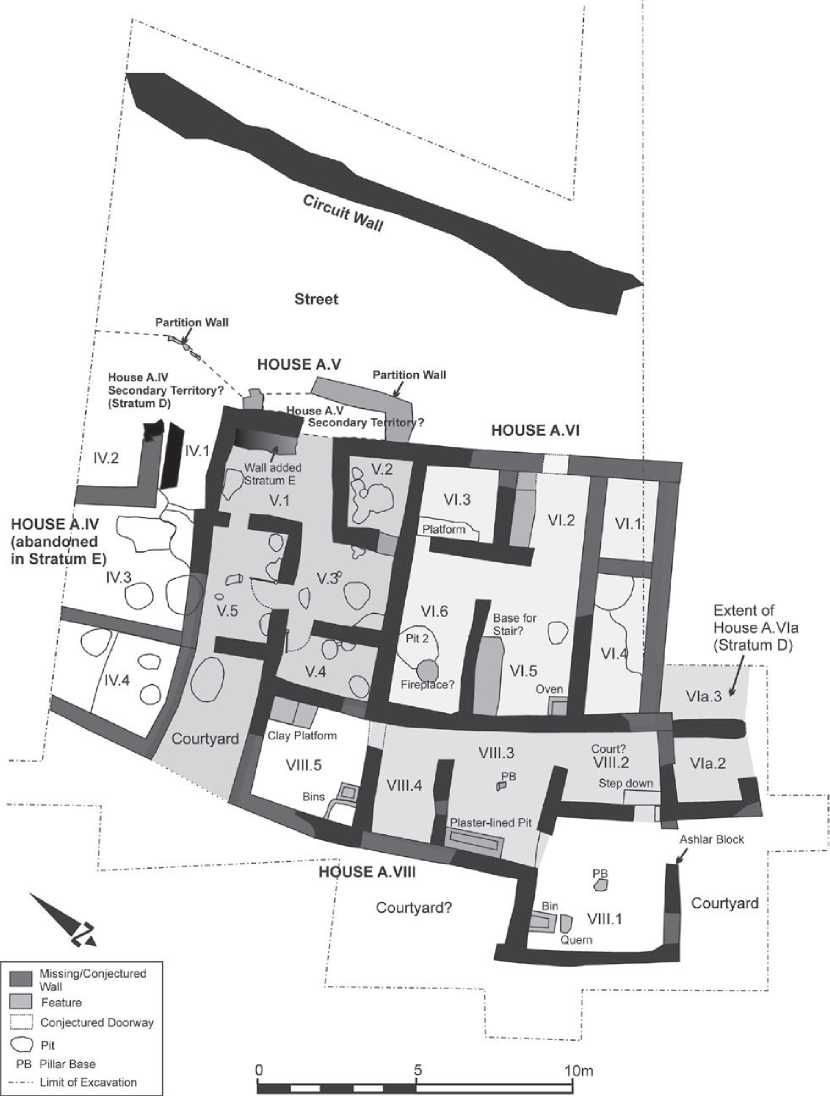

The importance of boundary maintenance is also apparent in the number of LC houses that show evidence of rebuilding on the same or nearly identical plan. For example, at LC IIIA Episkopi-Bamboula, the houses of Area A were destroyed at the end of Stratum D (Weinberg 1983:9-26). Houses A. V and A. VI were rebuilt in Stratum E using the same layout by leveling the debris, raising the floors and thresholds, and constructing new walls directly on top of the old foundations (Figure 6.10). Such continuity is not merely a demonstration of enduring property ownership, but indicates a constancy of dwelling that materialized a househoLd's attachment to a particular place through the accumulation of meanings and the formation of individual and collective memories (Ingold 2000:175; Zerubavel 2003:41). Attempts to demonstrate such continuity of spatial use and control were an essential part of place-making throughout the urban social hierarchy.

In spite of such efforts aT boundary demarcation and maintenance, LC urban landscapes were also places of negotiation, fluidity, and change. House A. VIII at Episkopi was built de novo in Stratum E and extended beyond the remains of House A. VIa, which it replaced, whereas House A. IV went out of use (see Figure 6.10), demonstrating that urban development was a dynamic process as some households in a given neighborhood grew or contracted; owners vacated, transferred, or subdivided their properties - processes that were materialized in the unique biographies of individual houses (see Tringham 1995; During 2005). The transformation oF the Fortress at Enkomi from a freestanding monumental building and center of power at the beginning of the LC period, to a series of non-monumental domestic units that formed part of an urban block in LC II-III also attests to this dynamic (Fisher 2007:199-217; Pickles and Peltenburg 1998).

A notable example of the ambiguity of some boundaries can be seen in the design of the large external courtyards that fronted Complexes A, B, anD D at Pyla-Kokkinokremos (see Karageorghis and

Figure 6.10 Episkopi-Bamboula, Area A (Stratum E, twelfth century BC). Schematic plan showing houses A. IV, A. V, A. VI (now abandoned) and the newly built A. VIII. Shaded area in House A. VIII shows extent of earlier House A. VIa (from Stratum D). Note appropriation of street space by House A. IV (Stratum D) and House A. V (Strata D and E) (adapted by author from Weinberg 1983:figures 7, 23, and 24).

Demas 1984:6-32; Figure 6.8). The fact that these courtyards appear to have been completely open to the space in front of the houses - presumably a street - indicates that they were intended to be both readily accessible and completely visible from the street. The function of these courts is unclear. The one in Complex A (Room 34) was not entirely excavated, while three ashy deposits that may have been hearths were found in the court in Complex D (Room 28). The court in Complex B (Room 22) contained a bronze "foundry hoard" hidden in a pit, as well as a fragmentary pithos and another pit containing copper slag, but with no associated ash (thus, likely ruling out metallurgical activity). The courts otherwise contained no built features. Although it is possible that their boundaries with the street were regulated through implicit norms or conventions (e. g., Lawrence 1990:77), the lack of a material border is rather unusual given the tendency to define spaces architecturally in LC IIC-IIIA urban environments, and introduces opportunIties for negotiation and contestation. I would argue that these spaces were likely what Altman (1975) refers to as secondary territories, which are accessible to a wider range of users, although regular occupants often exert some degree of control over who can enter a space and their behavior. Because secondary territories combine public or semipublic access with control by regular occupants, there is potential for uncertainty and social conflict as boundaries are established, tested, and violated (Altman 1975:114; see also Lawrence's [1990] discussion of "collective" spaces).

MAKING THE FIRST CITIES ON CYPRUS

In addition to the negotiation invited by the ambiguous boundaries of these transitional spaces, there is evidence suggesting that the efforts of ruling elites to impose order through top-down urban planning were sometimes undermined by bottom-up actions of individual households. In some cities, there are instances of households laying some claim to sections of what would appear to be public streets. At Maa-Palaeokastro, a screen made of wooden posts and other perishable materials was erected, running perpendicular to the east wall of Room 73, blocking off part of the open space (likely a street) between Buildings II and III (Karageorghis and Demas 1988; see Figure 6.9). Elsewhere, the owners of Houses A. V and A. IV at Episkopi-Bamboula (Stratum D) constructed partition walls in front of their houses using wooden posts or shallow trenches and field stones, thereby appropriating part of the street that ran inside the circuit wall (Figure 6.10). The relative permanence of this arrangement is seen by the fact that the wall in front of House A. V was

Rebuilt along with the rest of the house in Stratum E. The placement of new tombs in the streets and open areas in Area E at Episkopi-Bamboula (Benson 1972; Weinberg 1983:hgure 25) and aT Alassa-Pano Mandilaris (Hadjisavvas 1986) was one of the most potent symbols of the contesting, if not appropriation, of public space and indicates that at least some streets were deemed by adjacent households as a secondary territory or collective space. These acts of place-making suggest that even established, well-marked boundaries could be ignored, challenged, or at least open to negotiation. The success or permanence of such actions likely depended on the existence and degree of enforcement of norms or laws regarding the use of space established at the neighborhood and city levels, as well as the changing sociopoLitical and economic fortunes of the people involved.

World History

World History