While still a young man, Orson Welles (born 1915) was directing unusual productions of theatrical and radio plays. For example, in 1936 he staged Macbeth with an all-black cast and set it in a Haitian jungle. In 1938, he gained nationwide notoriety with a radio adaptation of H. G. Wells's The War of the Worlds, treating it as a news bulletin and panicking thousands of listeners who believed that a Martian invasion was in progress.

In 1939, Welles was put under contract by RKO. His first completed project was Citizen Kane, one of the most admired of all films. Welles received an extraordinary degree of control over his work, including the right to choose his cast and to edit the final film. Not surprisingly, the resulting film was controversial. It was a veiled portrait of publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst and his longterm affair with film star Marion Davies. Hearst tried to have Kane suppressed, but it was released in 1941, with many audiences being aware of its subtext.

Both the narrative structure and the style of Kane are dazzlingly complex. Beginning with the death of Charles Foster Kane, the film switches to a newsreel that sketches out his life. A reporter is assigned to discover the meaning of Kane's mysterious last word, "Rosebud." He interviews people who had known Kane, and a series of flashbacks reveals a contradictory, elusive personality. Ultimately the reporter's quest fails, and the ending retains an ambiguity rare in classical Hollywood films.

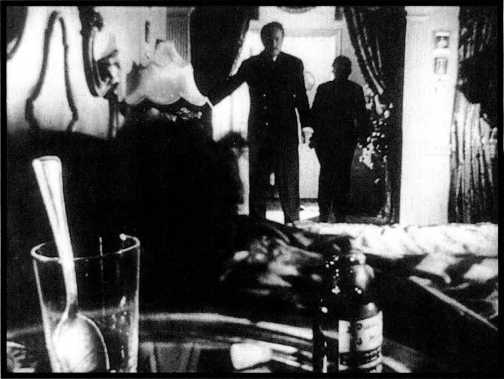

Stylistically, Kane was flamboyant, drawing extensively on RKO's resources. For some scenes, Welles used quiet, lengthy takes. Other passages, notably the newsreel and several montage sequences, used quick cutting and abrupt changes in sound volume. To emphasize the vast spaces of some of the sets, Welles and cinematographer Gregg Toland worked at achieving deep-focus shots, placing some elements close to the camera, others at a distance (see

10.14). Recent research has revealed that many of these deep shots were made using several types of special effects

(10.24). Optical-printer work combined several tracking shots imperceptibly into one (as in the crane shot through a nightclub skylight, where a flash of lightning hides the joint between two shots) and made the sets more impressive by combining miniatures and matte paintings with real-size sets. It has been claimed that over half of Citizen Kane's shots contain special effects. The sound track was also altered substantially after filming. All these stylistic as-

10.24 In this shot from Citizen Kane, the large objects in the foreground were filmed separately and combined with the set and actors beyond.

Pects of Citizen Kane proved highly influential during the 1940s.

Welles's second RKO feature was The Magnificent Ambersons. The plot does not use flashbacks, but it covers a lengthy period, the decline of a wealthy family as industrialization encroaches on a midwestern town. Welles establishes a nostalgic atmosphere in a prologue, narrated by him, which is a montage sequence depicting turn-of-the-century life. The film gradually adopts a grimmer tone as this genteel lifestyle disappears.

Stylistically, Ambersons takes Kane's techniques in less extravagant directions. Still, there are elaborate camera movements, as when Aunt Fannie has hysterics and the camera tracks through several rooms as Georgie tries to calm her. The deep-focus effects were more often done in a single exposure (see 10.15), and a larger budget allowed Welles to build entire sets and downplay optical-printer work.

After adverse audience reactions at previews, RKO took Ambersons out of Welles's control and cut it drastically, adding scenes made by the assistant director and editor. This truncated version was given a minor release. No complete version of the film survives, but even so it remains a flawed masterpiece. (See "Notes and Queries" at the end of this chapter.) did choreography for Busby Berkeley films, including Strike Up the Band (1940), and then graduated to directing with Cabin in the Sky (1943), a musical with an all-star black cast. His most celebrated film of the war era was Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), with Garland.

Other new directors of this era appeared from the ranks of screenwriters. Preston Sturges wrote scenarios during the 1930s, working on The Power and the Glory (1933, William K. Howard), a film with a complex flashback structure that was a precursor to Citizen Kane. Sturges began directing with The Great McGinty (1940), a political satire, and went on to make a string of popular comedies throughout the war years. In The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944), for example, he poked fun at American prudishness. A young woman winds up pregnant after a wild party and claims that she married the father (whose name she remembers only as being something like “Ignatz Ratskywatsky”). When he proves hard to locate, her mild-mannered boyfriend helps her avoid disgrace by marrying her; she then bears sextuplets, and the family becomes the focus of a media furor. Despite toning down by the MPPDA, the film remains audacious. For a while, Sturges was one of Paramount’s most popular directors.

John Huston, who had worked on the screenplays of Jezebel and High Sierra, was another scriptwriter-turned-director. Later in this chapter we shall discuss his directorial debut, The Maltese Falcon, as an early instance of film noir. Huston was in the military for much of the war, making some major war documentaries, and returned to Hollywood after 1945.

Orson Welles, the most influential director to emerge between 1930 and 1945, had already achieved success in a number of other fields including stage and radio (see box p. 227).

Several wartime films was Shadow of a Doubt (1943). A man driven to seduce and kill rich widows visits his sister’s family in a small California town. He charms everyone, but his young niece is shattered when she ferrets out the truth about him. Through location shooting, Hitchcock created a sense of small-town normalcy with which to contrast the villain’s secret crimes.

The German exodus to Hollywood that had begun in the silent era accelerated after the Nazis gained power in 1933. Fritz Lang arrived in 1934. Although he was able to work fairly steadily (about a film a year up to 1956), Lang seldom had much control over his projects and never gained the prestige he had had in Germany. He worked in many genres, making Westerns, spy pictures, melodramas, and suspense films. You Only Live Once (1937) is the affecting story of a young ex-convict who tries to go straight but is falsely accused of a murder; he escapes from jail the night before his execution, but he and his wife are hunted down and shot.

Billy Wilder had been a scriptwriter in Germany and resumed this career in Hollywood, teaming up with Charles Brackett on many screenplays, including those for Ninotchka and Ball of Fire. His first solo directorial effort was a comedy, The Major and the Minor (1942), and his grim study of alcoholism, The Lost Weekend (1945) was voted an Oscar as best picture. Although Otto Preminger was Jewish, he was brought to Hollywood to play Nazi villains. He managed, however, to slip into directing in the early 1940s. Wilder and Preminger made two of the period’s classic films noirs.

World History

World History

![Black Thursday [Illustrated Edition]](/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432470149_1431513568_003514b1_medium.jpeg)