King of England (1189-1199) and one of three leaders of the Third Crusade (1189-1192).

Born on 8 September 1157, Richard was the second surviving son of Henry II, king of England, and Eleanor of Aquitaine. He joined the family rebellion against his father in 1173-1174 but thereafter governed Aquitaine on the king’s behalf with the title of count of Poitou, winning a considerable reputation as military leader and determined ruler. When his elder brother, Henry “the Young King,” died in 1183, Richard became the principal heir to England and the Angevin family’s vast possessions in France. From then on, relations with both his father and the new king of France, Philip II, were tense. Richard was widely praised for being the first prince north of the Alps to take the cross in response to the fall of Jerusalem to Saladin in 1187. Yet by doing this without consulting his father, he exacerbated the political tensions, which meant that neither Richard nor the kings of France and England had actually left for the East by the time Henry II died (6 July 1189).

Installed as duke of Normandy on 20 July, then anointed king of England at Westminster on 3 September, Richard focused all his energies on the crusade. The religious obligation to recover the patrimony of Christ coincided with family duty to restore the kingdom of Jerusalem to his cousins, the junior branch of the Angevin family, and its king, Guy of Lusignan, who had been one of his own Poitevin subjects. Richard took over the treasure accumulated by his father, including the yield of the Saladin Tithe, but set out to increase the size of his war chest by all possible means. He reorganized the government of England, taking large sums from those who received the offices and privileges they bid for; this was standard practice, but the scale and speed of Richard’s operations were unprecedented.

To his younger brother John, lord of Ireland, Richard gave great estates in England, while assigning the castles to ministers he trusted, first William de Longchamp and then Walter de Coutances. This did not prevent John from rebelling in 1193 while Richard was a captive, but probably nothing could have done so. Richard also took care to secure his frontiers. Conferences with William the Lion, king of the Scots, and Welsh princes were successfully concluded. Alone of all the major French princes, his old enemy Raymond V of Toulouse had not taken the cross, so to protect his southern dominions, Richard promised to marry Berengaria, daughter of King Sancho VI of Navarre. These negotiations had to

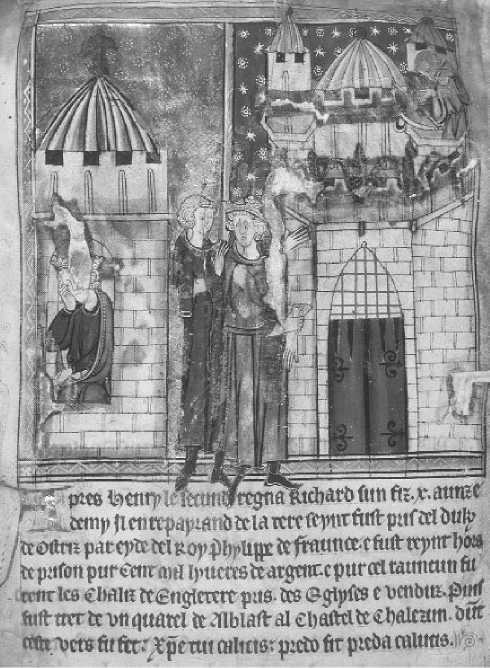

Two scenes from a life of Richard I of England, fourteenth century. On the left Richard is shown languishing in prison in Germany; on the right he is mortally wounded in the shoulder by a crossbowman at Chalus. (HIP/Art Resource)

Be kept secret because Richard had been betrothed to Alice, King Philip’s half-sister, since 1169. Humiliating Philip by discarding her now would have meant the end of the crusade before it started.

Richard and Philip finally left Vezelay on 4 July 1190, having agreed that they would share equally the gains made on crusade. Richard had arranged to rendezvous at Marseilles with the huge fleet that he had raised in England, Normandy, Brittany, and Aquitaine. When the fleet was delayed, he hired ships to send one contingent ahead to the siege of Acre (mod. ‘Akko, Israel) and made a new rendezvous at Messina in Sicily, where he arrived on 23 September. The customary winter closure of Mediterranean shipping lanes meant that he and Philip now had to stay there until the spring. While in Sicily, Richard secured the release of his sister Joanna, who had been kept in close confinement by King Tancred since the death of her husband, William II (1189). However, Tancred withheld both her dower and the legacy that William II had bequeathed as a crusade subsidy to Henry II, and that Richard now claimed as his.

When rioting broke out in Messina, Richard’s troops took the city by force (4 October). Two days later, Tancred agreed to pay 20,000 ounces of gold in lieu of Joanna’s dower, plus a further 20,000 that Richard promised to settle on Tancred’s daughter when she married his nephew Arthur of Brittany (d. 1203), who was now declared his heir presumptive. In return, Richard agreed that while in Sicily he would help Tancred against any invader, a provision directed against threats from Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor. In March 1191, Berengaria, escorted by Richard’s mother, Eleanor, arrived. Philip now had to release Richard from the betrothal to Alice, fearing that Richard would produce witnesses to testify that she had been his father’s mistress. From now on, Philip’s crusade was directed as much against Richard as against Saladin. He sailed from Messina a few hours before Berengaria arrived and, on reaching Acre, threw his weight behind Guy of Lusignan’s bitter rival, Conrad of Montferrat.

On 10 April Richard’s 200 ships left Messina. Some ships, including the one carrying Joanna and Berengaria, were blown off course and eventually anchored off Limassol on Cyprus. Isaac Doukas Komnenos, the self-proclaimed Greek emperor of Cyprus, plundered two wrecked ships and evidently intended to take Joanna and Berengaria captive. When the rest of the fleet arrived, Richard led a daring amphibious assault, capturing Limassol on 6 May. That night, he had the crusaders’ horses disembarked, and at dawn the Cypriot army camp fell to a surprise attack. When peace talks broke down, Richard set about the conquest of the island. When he captured Isaac’s daughter, the emperor surrendered. By 1 June Richard was master of the island. Whether or not the conquest of Cyprus had been planned (as seems likely) during the winter months in Messina, it was a strategic masterstroke, vital to the survival of Outremer.

Richard finally joined the Christian army besieging Acre on 8 June 1191 and at once opened negotiations with Saladin. Confronted by Richard’s siege equipment and galleys, the exhausted Muslim defenders of Acre capitulated on 12 July. The crusaders massacred most of their prisoners on 20 August when Saladin did not keep to the agreed terms regarding ransoms for their release. Richard and Philip divided the booty between themselves, to the exclusion of Leopold V, duke of Austria, and others. On 28 July the two kings adjudicated the competing claims to the kingdom, awarding it to Guy for his lifetime and thereafter to Conrad. However, Philip, repeatedly outshone by a king whose war chest had been replenished in Cyprus, left for France on 31 July, leaving his troops under the command of Hugh III, duke of Burgundy. In Leopold and Philip, Richard had made two enemies, and they returned to the West ahead of him.

The crusaders began their march to Jerusalem on 25 August. The pace was slow, but Saladin could not break their disciplined advance. On 7 September he risked battle at Arsuf; but Richard’s tactical control brought victory when the crusaders were on the brink of defeat. On 10 September the crusaders reached Jaffa (mod. Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel). They needed a rest, and Jaffa’s walls, which Saladin had dismantled, had to be rebuilt. Richard was already thinking in terms of the thirteenth-century strategy that the keys of Jerusalem were to be found in Egypt. Nearly all the troops, however, were passionately in favor of the direct route. After rebuilding the castles on the pilgrims’ road from Jaffa, the army reached Beit Nuba, 19 kilometers (12 mi.) from Jerusalem, soon after Christmas. But although the crusader war of attrition had forced Saladin to disband the bulk of his troops, he stayed in Jerusalem. The crusaders’ own logistical problems meant that even if they managed to take the city, they did not have the numbers to occupy and defend it; many crusaders, having fulfilled their pilgrim vows, would at once go home. An army council decided to move on Ascalon (mod. Tel Ashqelon, Israel), a step in the direction of Egypt that Hugh of Burgundy refused to take.

Richard entered Ascalon unopposed on 20 January 1192, but while rebuilding its walls, he was forced to return to Acre to deal with an attempted coup by Conrad of Montferrat. The coup made it clear that once Richard had gone, Guy would be no match for Conrad. In April 1192 Richard summoned a council, which offered the throne to Conrad and compensated Guy by selling him Cyprus for a down payment of

60,000 bezants. But Conrad was assassinated on 28 April. Inevitably Richard’s enemies blamed him, an accusation lent plausibility by the marriage of Conrad’s widow, Isabella, to Richard’s nephew and ally Henry of Champagne (5 May). Yet Henry was also King Philip’s nephew, well placed to reconcile the factions. On 22 May Richard captured Darum, an ideal base from which to disrupt the caravan route between Syria and Egypt.

Bowing to popular demand, Richard made another attempt on Jerusalem. By 29 June the entire crusader army was at Beit Nuba again. But once again, an army council, faced by reality, decided to withdraw and target Egypt instead. Duke Hugh left the army. Richard reopened negotiations with Saladin; he was at Acre when he was taken by surprise by the news that the Muslims had launched an attack on Jaffa. His galleys reached Jaffa just in time for him to lead an assault onto the beach and into the town. Four days later he beat off a dawn attack on his camp outside Jaffa in circumstances that humiliated Saladin and confirmed Richard’s legendary status. Richard fell ill, but Saladin’s troops were war-weary. A three-year truce was agreed on 2 September. Richard had to hand back Ascalon and Darum; Saladin granted Christian pilgrims free access to Jerusalem. Many crusaders took advantage of this facility, but not Richard. He was not well enough to set sail until 9 October 1192. He had failed to take Jerusalem, but the entire coast from Tyre (mod. Sour, Lebanon) to Jaffa was now in Christian hands, as was Cyprus. Considered as an administrative, political, and military exercise, Richard’s crusade had been an astonishing success.

In December 1192 Richard was seized on his journey home by Leopold of Austria, who later handed him over to Emperor Henry VI. Richard’s provisions for government during his absence stood up well to this unforeseeable turn of events. John’s rebellion was contained and a huge king’s ransom raised. Once the emperor had received 100,000 marks, and hostages for the amount (50,000 marks) still outstanding, Richard was freed (February 1194). But by then Philip had captured some important frontier castles in France; Richard devoted the remainder of his life to recovering them. This task, which involved building the great fortress of Chateau-Gaillard, was almost complete when he was fatally wounded at Chalus. He died on 6 April 1199 and was buried at Fontevraud.

To pay for his wars Richard made heavy financial demands on his subjects everywhere, not just in England. On crusade Richard was, in the words of a German chronicler, greater in wealth and resources than all other kings. In planning and organizing wars on the scale of the crusade or the recovery of his dominions in France, he was a cool and patient strategist, as much a master of sea power as of land forces. Friends and enemies alike testified to his individual prowess and valor; these qualities at times endangered his life, but they impressed enemy troops as well as his own. In his lifetime he was already known as Cxur de Lion (“Lion-heart”). Understanding the value of this reputation, he preached what he practiced; the letters in which he inflated his own achievements were intended for wide circulation.

According to King Philip’s panegyrist, Guillaume le Breton, had Richard been more God-fearing and not fought against his lord, Philip, England would never have had a better king. The Arab chronicler Ibn al-Athir judged him the most remarkable ruler of his time for courage, shrewdness, energy, and patience. His reputation as a crusader meant that he became a legend in his own lifetime and for many centuries was regarded as the greatest of all kings of England. But from the seventeenth century onward, that same reputation served to highlight his long absences from England and led to the view that he was woefully negligent of his kingdom’s welfare.

-John Gillingham

Bibliography

Flori, Jean, Richard Coeur de Lion: Le roi-chevalier (Paris: Payot, 1999).

Gillingham, John, Richard I (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999).

Gorich, Knut, “Verletzte Ehre. Konig Richard Lowenherz als Gefangener Kaiser Heinrichs VI.,” Historisches Jahrbuch 123 (2003), 65-91.

Kessler, Ulrike, Richard I. Lowenherz: Konig, Kreuzritter, Abenteurer (Graz: Styria, 1995).

Markowski, Michael, “Richard Lionheart: Bad King, Bad Crusader?” Journal of Medieval History 23 (1997), 351-365.

Mayer, Hans Eberhard, “Die Kanzlei Richards I. von England auf dem Dritten Kreuzzug,” Mitteilungen des Instituts fur Osterreichische Geschichtsforschung 85 (1977), 22-35.

Pringle, R. Denys, “King Richard I and the Walls of Ascalon,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly 116 (1984), 133-147.

Turner, Ralph V., and Richard R. Heiser, The Reign of Richard Lionheart: Ruler of the Angevin Empire, 1189-1199 (Harlow: Longman, 2000).

World History

World History