The crushing defeat of Loyalist forces at King’s Mountain, South Carolina, was a turning point in the Revolutionary War (1775-83) in the South and a sobering reminder that the conflict with Britain was also a brutal civil war. With the Battle of Savannah on December 29, 1778, and capture of Charleston on May 12, 1780 (see also siege of Charleston), and the overwhelming victory at Camden (August 16, 1780), the British commander, Charles, Lord Cornwallis, reasoned that the subjugation of North Carolina would not only secure the pacification of South Carolina and Georgia but also would lead to the invasion and conquest of Virginia. If that hotbed of revolution could be crushed, the rebellion might finally end. In preparation for the campaign, Cornwallis dispatched Major Patrick Ferguson into the northwestern region of South Carolina, where he was to recruit and train Loyalist soldiers, intimidate Whig sympathizers, and cover the left flank of the main army.

Having defeated a contingent of North Carolina militia, who then took refuge over the western mountains, Ferguson issued a message that if these men did not cease their opposition to British arms, he would cross the mountains, hang the rebel leaders, and ravage the area with fire and sword. Failing altogether to browbeat the enemy into submission, Ferguson’s words only made Whig militia units and civilians more determined to track him down and attack first. Two deserters from the revolutionary army warned Ferguson of the enemy pursuit, and, though only 35 miles from the safety of the main British army, he chose to make a stand at King’s Mountain.

The site was a curious choice for a seasoned veteran to have made. The Loyalists took a position on the widest portion of a bare, tapered ridge ranging from 60 to 120 yards wide, offering no readily available source of water, and whose summit was about 60 feet above the surrounding countryside. The slopes leading up to the ridge, however, were heavily wooded and provided excellent camouflage for an approaching enemy. Though time permitted and timber was readily available, Ferguson failed to reinforce his position with barricades. An elevated position also put Ferguson’s men at a disadvantage since firing downhill meant they would often overshoot their attackers, while the rebels firing uphill could easily hit the Loyalists at long range and from under cover of the trees.

Of the combatants at King’s Mountain, only Ferguson, a Scot, was not an American. Under his command were roughly 800 North and South Carolina Loyalist militia and 100 provincial infantry. Opposing them were approximately 940 men from the backcountry farms and villages of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, as well as hardened pioneers living in settlements west of the Appalachians

In what is now Tennessee. Unlike Ferguson’s troops, the revolutionaries had no formal training or discipline, no uniforms or supply train. They wore hunting shirts with buckskin leggings and moccasins, and each man carried his own food, bedding, and spare ammunition. Experience fighting Indians on the frontier had taught them savage no-quarter warfare. The most significant difference between the two armies was the weaponry. Most of the Loyalists carried smooth-bore muskets that had an effective range of about 90 yards, while the “back watermen” and “mongrels,” as Ferguson disparagingly called his adversaries, were armed with rifles. Though not fitted with bayonets, or as sturdy for use as a club in hand-to-hand fighting as were muskets, these weapons had a killing range of 300 yards.

Ferguson’s arrogant belief in the superiority of his men over undisciplined frontiersmen and militia, along with his apparent overestimation in the strength of his position spelled his ruination. His attackers divided into two columns, surrounded the ridge on both sides, and advanced from all directions. The Loyalists countered with bayonet charges down the hill, which was a difficult task on the wooded slopes. The revolutionaries simply fell back, reloaded, and renewed their assault. As the Loyalists retreated back up the hill to the barren summit, they were easy targets for the enemy riflemen. When the encirclement of the ridge tightened, some Loyalists tried to surrender, but Ferguson twice cut down their white flags. Finally, in a desperate attempt to break through the enemy line, Ferguson led a mounted charge that resulted in his death and that of every man who followed him. When his second in command tried to capitulate, some of the attackers shouted “Tarleton’s quarter,” and kept killing Loyalists even after the white flags were raised, in retribution for the massacre by British dragoons of Virginians who had surrendered at the Waxhaws. The Loyalists suffered 119 killed, 123 wounded, and 664 captured. Revolutionary losses were extremely light, with only 28 killed and 62 wounded.

The victory boosted flagging morale among the revolutionary forces, who had suffered a string of military defeats, and paved the way for the resurgence of the Continental army in the South. For the British, the defeat of the king’s forces by militia and civilians thoroughly intimidated would-be sympathizers of the Crown in the Carolinas and forced Cornwallis to delay the invasion of North Carolina.

Further reading: Henry Lumpkin, From Savannah to Yor-ktown: The American Revolution in the South (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1981); Hank Messick, King's Mountain: The Epic of the Blue Ridge “Mountain Men” in the American Revolution (Boston: Little Brown, 1976).

Knox, Henry (1750-1806) Revolutionary War officer, first U. S. secretary of war

Henry Knox was one of George Washington’s most competent and trusted officers in the Revolutionary War (1775-83), who moved quickly through the ranks to become major general by the end of the war. He also served as secretary of war under the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution.

Knox came from humble beginnings. He was apprenticed to a bookbinder as a young boy and opened his own bookstore on his 21st birthday in Boston. Although most of his customers consisted of British officers and their wives, he strongly identified himself with the colonies rather than Great Britain. Despite a hunting accident where he lost two fingers of his left hand, he joined the Boston Grenadier Corps in 1772 as second in command under Captain Joseph Pierce. While serving in the regiment he studied military science, specializing in artillery warfare and logistics. In 1774 he married Lucy Flucker, the daughter of the royal secretary of Massachusetts.

At the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, he left Boston with his family and joined the forces that became the Continental army. Knox met and impressed Washington soon after the Virginian took command of the revolutionary army in June 1775. Washington put Knox in charge of

Transporting the cannon captured at Fort TicoNDEROGA to the troops surrounding Boston. When this heavy artillery was placed atop Dorchester Heights in March 1776, the British were compelled to evacuate the city. Washington made Knox a colonel in the artillery. That summer Knox was stationed at the Battery in New York but had to retreat when General William Howe seized the city in the summer of 1776. Knox saw action in several battles, including the Battles of Trenton and Princeton (December 26, 1776 and January 3, 1777) and the Battle of Brandywine (September 11, 1777), and he spent the winter in Valley Forge (1777-78) with Washington. He was promoted to brigadier general after the fighting in Trenton.

Knox served most of the rest of the war with the army and was at the surrender at Yorktown (October 19, 1781). He was made major-general in 1782. He spearheaded the effort to sustain the camaraderie of the officer corps in the establishment of the Order of Cincinnati in 1783. After the British evacuated New York City (November 24, 1783), he triumphantly led his troops into the city.

Knox became secretary of war in 1785 under the Confederation government. Once the Constitution replaced the Articles of Confederation in 1789, he became President Washington’s secretary of war. In this position Knox supervised the construction of coastal fortifications and helped to establish the U. S. Navy in 1794. He was also responsible for relations with Native Americans, encouraging negotiations as much as possible. Knox oversaw the military conflict with the Indians of the Old Northwest in the 1790s, which culminated in the Battle of Fallen Timbers (August 20, 1795). By the time of the victory in Ohio, which reflected the success of his determination to create a more professional army, Knox had retired from public office (on December 31, 1794) and returned to Maine and his estate at Montpelier.

Further reading: North Callahan, Henry Knox, General Washington’s General (New York: Rinehart, 1958).

Knyphausen, Wilhelm, Baron von (1716-1800) German commander with the British army Baron Wilhelm von Knyphausen commanded the so-called Hessians for much of the Revolutionary War (177583). Born into an aristocratic German family, Knyphausen joined the Prussian military in 1734 and rose to the rank of lieutenant general by 1775. He arrived in North America in October 1776 and was second in command among the Germans to General Leopold Philip von Heister. Knyphausen led the Hessians in the crucial attack at the Battle of Fort Washington (November 16, 1776) and assumed overall command of the German mercenaries after the British disasters at the Battles of Trenton and Princeton (December 26, 1776, and January 3, 1777). At the Battle of Brandywine (September 11, 1777), Knyphausen commanded the crucial frontal assault across Brandywine Creek as Charles, Lord Cornwallis attacked from the flank. After 1778 Knyphausen was stationed in New York City. During General Henry Clinton’s southern campaign in 1780, Knyphausen was left in charge in New York. Although he did not participate in any other major battles, he commanded several incursions into the surrounding territory occupied by the revolutionaries, including the sortie in New Jersey that led to the Battles of Connecticut Farms (June 7, 1780) and Springfield (June 23, 1780). Toward the end of the war Knyphausen’s health became a problem, and he retired from British service in 1782. He later became military governor of Cassel in Germany.

KoSciuszko, Tadeusz (1746-1817) Continental army general and first major foreign volunteer in the American Revolutionary War

A transatlantic revolutionary, Tadeusz (sometimes Thad-deus) Kosciuszko was born in Poland. Educated by an uncle and at the Jesuit College at Brest in France, he soon began an extensive study of military science. After graduating from the Royal Military School in Warsaw in 1765, Kosciuszko went on to the Ecole Militaire in Paris. He immersed himself in the study of artillery and military engineering. He returned to Poland in 1774 and found the Polish army to be a shadow of its former self. A failed courtship to the daughter of a nobleman added to Kosciuszko’s discontent.

The Revolutionary War (1775-83) provided the restless Kosciuszko with an opportunity to use his military skills. The rhetoric of republicanism also fit nicely with the liberal philosophy he had been exposed to while in France. With borrowed money, Kosciuszko traveled to North America, where in October 1776 he received a commission as colonel of engineers in the Continental army. Kosciuszko’s counsel was not followed at Fort Ticond-ERoga, which the British captured on July 6, 1777. However, during the campaign that led to the British surrender at Saratoga (October 17, 1777), Kosciuszko oversaw the fortifications that prevented the British from marching down the Hudson River valley. Kossciuszko continued to direct the successful construction of fortifications, most notably at West Point, New York, and Charleston, South Carolina. During the later years of the war, he served as General Nathanael Greene’s leading military engineer and fought in many of the southern battles in the last two years of the war. After the war, Kosciuszko was granted U. S. citizenship, land, and the rank of brigadier general.

He went back to Poland in 1784 and fought against the Russians in 1792. Despite Kosciuszko’s efforts, the complicated dynastic politics of central Europe led to the second

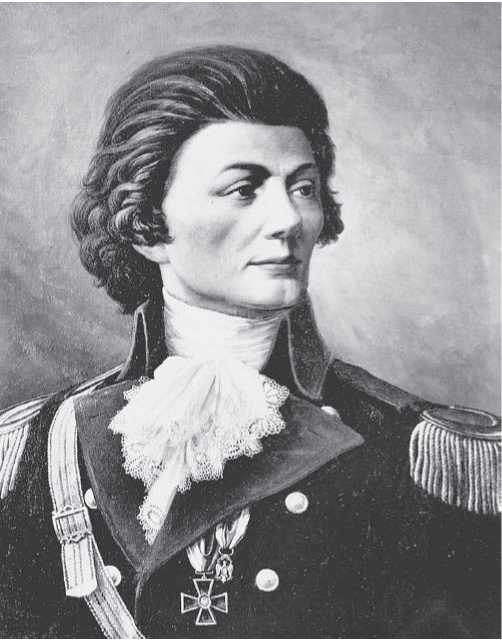

Polish officer Tadeusz Kosciuszko (Independence National Historical Park)

Partition of Poland, between Russia and Prussia. Forced into exile in 1793, Kosciuszko organized a failed uprising against the Russians in 1794, which led to the third partition of Poland and the end of an independent Polish state in 1795. Badly wounded on the battlefield, Kosciuszko was captured and then imprisoned in St. Petersburg. Released in 1796, Kosciuszko returned to the United States in 1797, saw many of his revolutionary compatriots, and lived in Philadelphia for less than a year. In 1798 Kosciuszko sailed for France, hoping to gain support for his native Poland. However, Kosciuszko did not trust Napoleon Bonaparte and did not join the French; nor could he return to Poland. Instead he remained an exile and died in Switzerland. Before his death, in a final demonstration of his support for the ideal of liberty, he freed the serfs on his Polish estate. Kosciuszko also offered Thomas Jeeeerson a unique opportunity to relieve himself from what both men saw as the burden of slavery. Kosciuszko’s will authorized “my friend Thomas Jefferson” to use Kosciuszko’s property in the United States “in purchasing negroes from among his own as any others and giving them liberty in my name in giving them an instruction in trades and otherwise, and in having them prepared for their new condition in the duties of morality which may make them good neighbors, good fathers or mothers, husbands or wives and in their duties as citizens, teaching them to be defenders of their liberty and country and of the good order of society and in whatsoever may make them happy and useful.” Jefferson never acted upon this bequest.

Further reading: Miecislaus Haiman, Kosciuszko in the American Revolution (New York: Gregg Press, 1972); Gary B. Nash and Graham Russell Gao Hodges. Friends of Liberty: Thomas Jefferson, Tadeusz Kosciuszko, and Agrippa Hull: A Tale of Three Patriots, Two Revolutions, and a Tragic Betrayal of Freedom in the New Nation (New York: Basic Books, 2008); James S. Pula, Thaddeus Kosciuszko: The Purest Son of Liberty (New York: Hippocrene Books, 1999).

World History

World History