The manners in which warriors fought are very much related to both the objectives of the confrontation and the weapons they carried and were experts on. Again, there is no evolutionary pattern in time or space. We can see the formation of early empires, in the Late Neolithic and the Bronze Age, based on elaborate armies composed of warriors who specialized in various weapons, using military strategies and, on the other hand, we can see warfare episodes many centuries later which show disorganized bands with incipient weapons and lack of any military strategy.

To fully understand weapons, one has to see them fit with a particular warrior and in the course of military action. This is the field in which they were designed and evolved. So we will review a few military actions as representative of this triangular symbiosis between soldier, weapons, and fight, and see how they become representative of types of warfare.

Raiding and mercenarism Raiding was probably the most widespread warfare model in prestate societies and survived throughout history until the twentieth century, sometimes in the shape of brigandage, as with the Brazilian Cangaceiros.

Raiding is a war expedition called and lead by one chieftain whom warriors decide to obey, although this may not last longer than the expedition itself. The reason is normally economical, the search for pillage, and sometimes revenge for prior attacks, but the hidden underlying reason is clearly sociological. Sometimes their society of origin has to export their military impetuosity which may cause excessive internal stress, and they leave in a quest for glory and wealth. They were engaged as mercenaries to fight in other country’s wars, incorporating larger armies, quite often acting as the first shock waves during battle, since they were expendable. This picture has a very early start in the history of warfare. Mercenaries acted as early as 1500 BC in Egypt under Ramesses II, and have been omnipresent where large armies needed an eclectic composition of wings composed by warriors specialized in the use of diverse weapons. Curiously, during many centuries this specialization retained an ethnic origin (Figure 12) associated to fighting expertise and typical weapons, like Balearic slingers, Scythian archers, or Numidian horsemen, thus adding to a multifunctional composition of the armies.

Figure 12 An example of a Viking warrior acting as a mercenary body guard to the Byzantine emperor. The Varangians were reputed Viking mercenaries known for their fidelity to the emperor to whom they became attached. During the tenth and eleventh centuries AD a substantial number of Viking warriors from the Scandinavian countries migrated to Byzantium to join this elite corps. Endemic widespread mercenarism is known in Europe and the Mediterranean from the Bronze Age onwards. Source: Vikings: Raiders from the North, Time-Life Books, Alexandria, Virginia, page 73. Mosaic from the church of Nea Moni, at Chios, Grece.

The early battle The remarkable economical growth and wealth attained in the area bound by Anatolia, Egypt, and Mesopotamia in Neolithic with the process of sedentarization produced powerful cities, city-states, and kingdoms. These centers of wealth needed protection and, thanks to social differentiation a class of specialized professional warriors was born, commanded by nobles and under the authority of a king. These armies were often increased with mercenaries of various sorts and tended to become organized in divisions according to the profile of the soldiers. It was soon discovered that dealing with such an army in battle called for organization. The choice of a particular ground, the use of a given association of soldiers during the battle, just to name two aspects, proved to be decisive and allowed the balance of outnumbering. So there was a prompt development of what we know as military strategy. The tactics and maneuvers brought up another need, that is, to communicate during the fight.

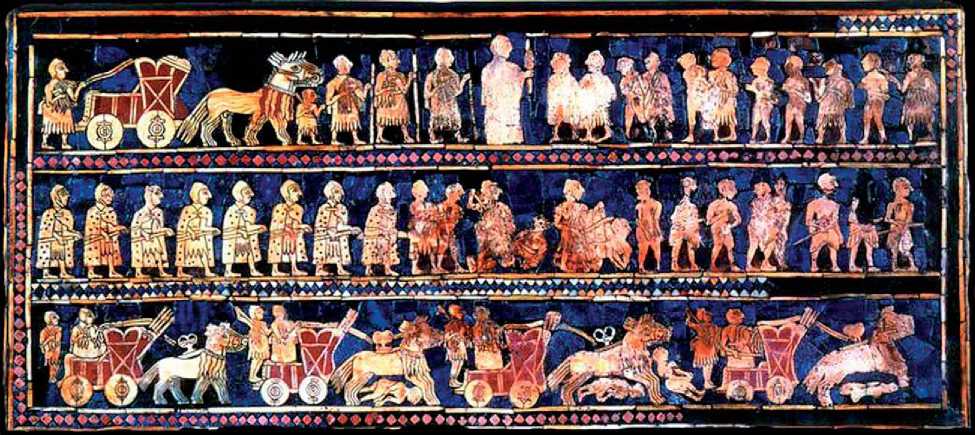

There is no available information for battles prior to the late fourth millennium BC, in Mesopotamia, and yet by around 2600 BC war appears to be endemic in the region. This is the date of an important artifact known as The Royal Standard of Ur, and one of the earliest representations of a Sumerian army in what appears to be a display of victory (Figure 13). The early use of bronze weapons was probably the reason for the Mesopotamian domination over the surrounding peoples. The depiction shows rows of infantry soldiers and war chariots, an archaic four-wheeled model, and a substantial number of subdued individuals, apparently prisoners, wounded, humiliated, and some struck with axes, being presented to the king. The uniformity of the warrior’s gear suggests professional soldiers organized in groups according to their weapons and fighting expertise. By this time, the same reality is depicted in Egypt, now united as one whole kingdom. From here on we learn that war will always be about power and domination; personal power over men and territory. This is the pictographic message from early antiquity to the present, covering the world and various diachronical cultures, which we will find in Egyptian pyramids and temples, American Maya and Inca temples, Greek and Roman domestic and public architecture, in addition to the newly established media of propaganda invented by the Greeks: the coinage.

With the emergence of the Hittite empire, war became more visible in both the archaeological and historical records. Weapons had developed substantially: the two-wheeled chariot was then much lighter and faster, bronze weapons were being overcome by iron weapons, and the Hittites gained substantial supremacy. Kingdoms and their territorial warfare range also enlarged. The battle of Kadesh, in 1274 BC, between Hittites and Egyptians, is a good example of both the changing configuration of war and the growing territorial scope of kingdoms. In addition, both sides employed mercenaries, the so-called Sea Peoples tribes from Asia Minor, and were organized into divisions.

The masters of war Much was achieved during the first millennium BC regarding armor and military science. The spread of iron brought new and more solid weapons, although bronze remained preferred for defensive weapons for quite some time.

This was a time where the Mediterranean regained leading role, and new empires were built, based on military excellence. The empire of Alexander and the Roman Empire set new standards in the way military resources were to be used.

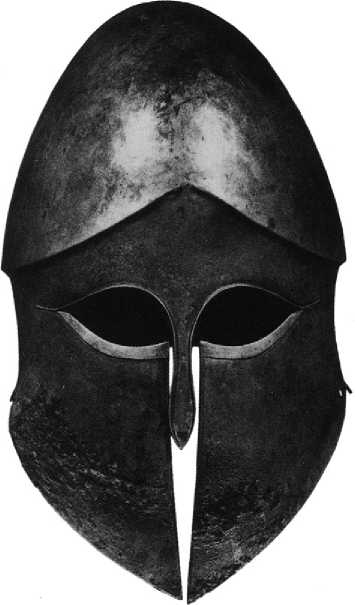

It all started with a new system of warfare: the phalanx, created in the late seventh century BC in Greece and based in the hoplite soldier. The hoplite was a heavy infantry soldier who was literally encased in bronze armor; a set that could weight over thirty kilos. From the seventh to the fifth centuries BC the panoply consisted of one helmet of Corinthian type, breastplate in bronze, greaves, a short sword, the hoplon shield (Figures 14 and 15) and one long spear. The fighting approach was good coordination,

Figure 13 The Royal Standard of UR. This is one of the earliest representations of an army on parade. Decorated panel from a Sumerian wooden artifact dated 2600 BC. Source: The British Museum.

Figure 14 Corinthian helmet (seventh to fifth centuries BC). The heavy protection conferred by this new type of helmet made it the head protection of choice for the hoplite soldiers. Source: Geoffrey Parker Cambridge Illustrated History of Warfare, Cambridge University Press, 2005, page 16.

Figure 15 Battle scene with two armies organized as phalanxes. The artist outlined a significant individuality in the armor of each soldier, mostly in the ‘hoplon’, the round shield. Corinthian vase dating to the second half of the seventh century BC, depicting what may be the oldest image of one phalanx. Source: Geoffrey Parker Cambridge Illustrated History of Warfare, Cambridge University Press, 2005, page 14.

Close ranks and effective weapons. Endemic warfare between the Greek city-states greatly improved the training of the close-rank battle, thus promoting discipline and cohesion.

A major turnover was to originate from Macedonia, where one warlord was unifying the city-states through war, and creating an extremely efficient military structure. With the victory at Chaeronea, over the Greeks, in 338 BC, Philip II established the beginning of the Macedonian hegemony. His untimely death two years later gave the power to his son Alexander the Great. Under these two leaders warfare was raised to a previously unseen level of expertise. Philip had created a military state where the phalanx was reshaped and closely articulated in battle with a lighter infantry corps, the hypaspists and other corps of projectile-thrower infantrymen, such as archers, spearmen and slingers, in addition to heavy cavalry strongly armored for impact. The lengthening of the sarissa to over four meters made it harder to handle, but improved phalanx efficiency, since five ranks could now block the enemy’s advance. At the same time, the shield and other protective gear became smaller and lighter. The phalanx was a surprisingly strong body and its progression was virtually unstoppable. However, it was ridiculously weak against side and rear attacks, or once enemies had penetrated the formidable barrier of spearheads.

This was the army Alexander took over and greatly improved by taking advantage of the remarkable coordination between cavalry, phalanx, and the other infantries, in addition to a permanent dialogue with military engineers. This tactical use of an army was entirely revolutionary and it became virtually invincible against the regular armies. A standard battle would start with throwing projectiles to shake the enemy’s lines, and then the cavalry strike to break the ranks, followed by light infantry, the hypaspists, to keep pressure while the slower phalanx came to make contact. The other innovation was purely strategic, and brought a new ideology of warfare: the classical frontal shock was replaced by mobility, a quest for the enemy’s vulnerable spots, and composite attacks often dealing with the adversary interaction, creating reaction through diversion maneuvers. This could not be done without extreme coordination, and herein lay Philip’s military legacy that Alexander used in conquering a reasonable portion of the known world.

The idea of phalanx and the composite army was established, and would define warfare for centuries to come. Before the unification of Rome, some of these approaches to war had been adopted by various peoples, amongst them the Etruscans. They were the source from which the Romans in the course of the fourth century BC raised their model of phalanx:

The legion. The new idea that the Romans developed was the one of a disciplined and united body which was more adaptable to the irregularities of the terrain during progression, and that could maneuver more swiftly without weak flanks. To add to this eclecticism, the larger unit was divided into smaller maneuverable maniples, which were transformed into cohorts by Marius’ reforms. In the third century BC Rome expanded very audaciously to gain the control of the western Mediterranean against both Macedonians and Carthaginians, and by the late second century BC her territories spanned the whole Mediterranean.

The Roman legion was accompanied by a vast complex of infrastructures, such as military engineers; medical personnel and infirmaries; tradesmen for supplies and to absorb loot and slaves; payroll service; arms and armor; weapon-smiths and carpenters; and even itinerant brothels. With expansion outside Italy, Roman legions developed a surprising self-sufficiency. They could build a military camp or a city; or build one bridge within a few days, as was done over the Rhine; build ships, catapults and siege machines; or even dig ditches miles long, as in Alesia, or ramparts to reach inaccessible hill-forts, such as in Massada. A military career was long lasting, although reduced to 16 years by Marius’ reforms, and so legions were supported by experienced and disciplined veterans, which accounted for coordination and adaptability to both terrain and maneuvers.

Republican period standard military equipment for infantry was the large curved rectangular shield (scutum), one heavy and highly penetrating throwing-javelin (pilum), and a short dagger. Chest protective armor was the metal lorica, of which there were several models, such as the segmentata (metal plates), the hamata (chain mail) and the squamata (fish scale plates). In addition, all infantrymen wore a helmet with cheek and neck guards. This set could vary with the soldier’s function and status, whether he was a velite or a triarius.

Working as a compact body, a Roman unit benefited from considerable protection, from shields bound together as a continuous surface. The penetrating power of a shower of pila had a damaging effect on the enemy’s armored ranks, thus adding to the effect of archers and slingers, (Figure 16) and also of the Roman and auxiliary cavalry. Upon impact, the legion might easy and effectively engage in melee combat, pushing the enemy with the shields while swiftly stabbing with the gladium.

Cavalry was a small prestige corps where young aristocrats could start their political career. To add to their small number, Gauls, Iberians, and Numidians were recruited as cavalry mercenaries. The cavalryman’s gear was a small round shield, one helmet normally

Figure 16 Slinger from an auxiliary corps of the Roman legion, represented on Trajan’s column, Rome. This is a very light foot-soldier without armor and only a side dagger to add to the sling. Source: Web source.

With mask, exclusively cavalry type, and body armor. The weapons were the gladium and one or more javelins.

Legionaries and cavalry were the core of legions, however, often largely reinforced by corps of auxiliaries who mastered different weapons and were mostly used as skirmishers.

The siege The spread of fortifications promoted a particular type of combat, with one party attacking both the fort and the besieged. Strategies and machinery devoted to this particular warfare evolved greatly with time; most were concerned with throwing projectiles against the wall and the defenders in order to damage both as much as possible. In the early sieges only simple weapons were available, such as slings, arrows and spears, and assault ladders, as recorded in the Egyptian sieges of Hatwaret and Meggido, in the second millennium BC. The Assyrians already used siege machinery, and this practice soon became extended. The battering ram was a very simple and effective weapon to demolish the gates, although the maneuverers were too exposed, and so it evolved in association with wheeled assault towers. The course of the first millennium BC was particularly prodigal in technological development of siege weapons, and tortoise sheds, ancillary machines, catapults and ballistae, became common in siege warfare. The projectile throwing devices also gained particular importance with naval warfare, and accompanied the evolution of both naval warfare and warships. Thudy-dides mentions a flame-throwing device, used against wooden fortifications, during the Peloponnesian wars; so technical excellence and originality was the trademark of this type of war, of which the Trojan Horse is just an example.

Siege machines were extensively used by Carthaginians to attack the Greek Sicilian cities during the second Punic War. The siege of Syracuse became an historical milepost due to the inventions of Archimedes and this was the first time a catapult was used, as claimed by Diodorus. Alexander The Great had greatly profited from this knowledge and tradition, and made a substantial development to siege engineering in the course of his campaigns. Although the development of the expertise attained by Greeks and Chinese in chemical and flaming projectiles was somehow neglected by Roman engineering, the more ‘conventional’ siege devices were greatly used and their field use developed during the formation of the empire. Siege weapons were transported, dismantled, and often built from scratch in the battle or siege area by army engineers.

Artillery, such as ballista and onager, were used in most military confrontations, not just for sieges but also to breach the ranks of enemy armies. They were used, respectively, to throw darts in a supposedly straight trajectory, and to throw any kind of projectile, such as stones or fireballs, in a curve shot. The damaging effect of these devices was added to by the work of Roman sappers, undermining the walls, and building tunnels under the defenses, while properly protected by shelters, the vinea. Battering rams were particularly effective for damaging both gates and walls, while its operators were comfortably protected by a tortoise cover that was covered with fireproof materials. The assault tower is what could probably be seen as the predecessor of today’s tank. It was armored, mobile, and carried weapons and soldiers as a fighting unit. This was a metal-plated well-protected mobile wooden tower, normally as high as the walls, which had several platforms to bear both soldiers and artillery weapons, rams and draw bridges to assault the walls.

From the Roman Empire to the end of the Middle Ages the siege became the most common form of warfare, and therefore fortification techniques evolved along with siege devices until the major changes imposed by firearms from the fourteenth century onwards.

The riding hordes The waves of mounted warriors - such as the Scythians, the Huns, and the Mongols - that emerged from the Euro-Asian steppes in several periods, provide significant examples of warfare superiority and innovative military strategies. The impressive speed with which these mounted armies deployed, not only in the battlefield, but also in the course of invasions, was often fatal to the enemy. These warriors mastered the use of their weapons, particularly the short composite bow, which they used charging at full speed on horseback while shooting arrows with astonishing accuracy.

While there were slight variations from tribe to tribe, in general Mongol light cavalry warriors wore a cuirass made out of lacquered leather strips, and protected their heads with hard leather helmets or traditional fur-trimmed Mongol caps, and also carried a shield covered in thick leather. As offensive weapons they had a short sword, two bows, for long and short range respectively, at least two quivers, a lasso, and a dagger strapped to the left forearm. The difference with heavy cavalry riders is that they used a scimitar instead of a short sword, carried a battle-ax or mace and a hooked spear. Under Genghis Khan, in the early thirteenth century, the Mongols conquered a vast territory from Eastern Europe to the China and Pakistan. They faced a greater diversity of enemies than any other army in military history, including Alexander. The nomads from the steppes, the European heavy cavalry (Figure 17) and a variety of Chinese armies, in addition to numerous defended cities - for all these the Mongols found particular strategies, never exposing themselves too much whenever they could be hurt by enemy superiority.

A standard battle would be based on two main movements: the approach of the cavalry, who often encircled the enemy at full gallop while dispatching clouds of arrows with impressive accuracy as they charged ahead, and the charge with heavy cavalry to break the enemy’s lines. However, the military success of the Mongols was not exclusive to the cavalry. The development of their expertise in military tactics, siege weapons and even psychological pressure enabled the fast advance of the Mongol army over vast regions. They used siege weapons and knowledge from the Greco-Roman period and added innovations by using technical information from the conquered peoples, mostly the Chinese. In the course of a siege of a city, a Mongol catapult would not only throw stone projectiles against the city walls, but would also throw corpses, infected with plague and other contagious diseases, inside the city. The other effective weapon was of a psychological nature: fear of the reputed Mongol savagery. Their self-sufficiency in supplies was original, since they could be in the field in permanent movement for over six months by eating horsemeat, mares’ milk and, in emergency, horse blood. Each horseman kept sixteen horses, sometimes more when long expeditions increased the need for supplies.

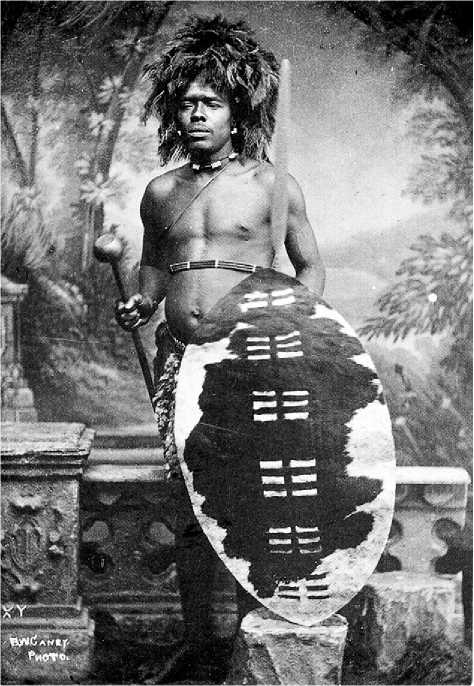

Barefoot warriors Another extremely effective use of swift and nimble light infantry with little weaponry can be found in the early nineteenth century Zulu army (Figure 18). Zulus were a small tribe who inhabited the south of Africa and, in the end of the eighteenth century, started very deep transformations which changed them from a peaceful people of shepherds into one of the most formidable armies of the time, under the command of Shaka, the mastermind of all these changes. Although the Zulu kingdom embodied a substantial part of the south of Africa, it was very ephemeral as a social and economical system. And yet Zulus faced, and sometimes defeated, armies with far superior firearms. All young men were engaged in the army from youth until the age of forty, thus becoming particularly well trained in fighting and enduring barefoot running over long distances. Zulu warriors wore verY little clothing and had no protection other than a oval shaped shield made with leather tied to a wooden frame. Their only weapon was a newly designed assegai, or short spear, of large blade, which they handled in a sword-like manner. Specializing in lightning-fast approach and

Figure 18 Image of a Zulu warrior in full combat gear. The light and thin leather shield was mostly used to divert the blows, rather than to absorb weapon frontal impact. The spear was the main attack weapon, and the new design introduced by Shaka made it halfway between a short spear and a long-handled dagger. Source: Web source.

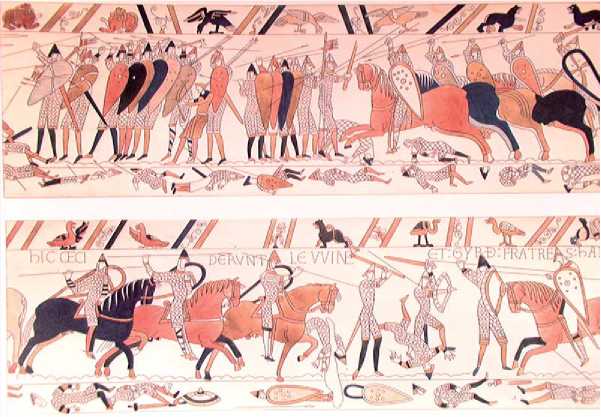

Figure 17 William the Conqueror invades Great Britain with his cavalrymen, in 1066, and faces Anglo-Saxon resistance at Hastings. The Bayeux embroidery is a pictorial tale of the whole expedition, and provides a remarkable insight info the fight and the weapons used by both sides, also illustrating the most typical soldier's protective gear. Source: Web source, Bayeux Museum.

Figure 19 Military display of cavalry and foot warriors followed by trumpeters. Some of the bowl-shaped helmets, probably Montefortino type, are topped by an animal figure of totemic nature. Horsemen wear spurs, and the horse gear set appears to be elaborate. Celtic and Germanic horsemen often acted as auxiliary troops in the Roman legions. The ‘Gunderstrup cauldron’, probably originating from Thrace, dates to the first century BC. Source: The Celts: Europe’s People of Iron, Time-Life Books, Alexandria, Virginia, page 62. © The National Museum of Denmark.

Charge, their combat technique was to push the enemy’s defense aside by striking sideward with the shield, and then striking the opponent in the stomach with the spear thus provoking a fatal wound. Battle strategy was similarly simple: the Zulu army presented a strong center to hold the enemy’s attention and two wings to encircle the flanks, in addition to one reserve, held in the army’s rear.

The sea raiders Like the Sea Peoples from the twelfth century BC, the Vikings, from the eighth to the eleventh centuries AD, were another fascinating combination of weapons, warrior valor and strategy, for whom the swiftness of deployment had an important role. Vikings were a people of farmers, craftsmen, and traders where warfare was a valued and prestigious activity. Their raids were recorded from the late eighth to the late eleventh centuries, and covered all the Atlantic shore down to the Portuguese coast.

The Viking warfare strategy was to sail along the coast, sometimes continuing up rivers, and to land taking by surprise cities and monasteries that then would be savagely pillaged. During the Viking era the Atlantic coast of Europe was almost permanently under siege, to the extent that some populations paid the Vikings a kind of protection fee in order not to be attacked.

Being mostly foot warriors, the gear of these horsemen would include one iron chain mail shirt, covering from chest to knee, one iron helmet in the shape of a rounded cap, and a wood round shield with a diameter of over one meter or less, reinforced by a metal boss. The offensive weapons were the wooden long bow, the spear, dagger, battle-ax, and the long sword, just under one meter long, which the warrior used single-handed in conjunction with the shield. However, probably the most important item in Viking raids was their particular ship, commonly known as the Drakkar. The ship, as described above, permitted to navigate in shallow shores and small rivers, and also allowed a fast and easy landing of the party. The conjunction of sail and oars made the Drakkar the fastest ship of its epoch for sea cruising, and the mobility it conferred gave Vikings a military supremacy in coastal Europe.

The ecological warfare Warriors from simple societies in the past and present were experts with their choice weapons, like the spear, arrow, mace, and battle-ax. They also appear to have taken an excessive zeal in decorating their bodies with massive ornaments and paintings, and sometimes even piercing. And yet, warfare appears to be performed not to kill enemies, nor to gain territory, nor to obtain loot. The Wintu people, of northern California, called off hostilities once someone was injured. In some warrior societies of the Indonesian and the Pacific islands and in southern Africa, and also among the pre-Zulu Nguni, for example, war, on the whole, became a very ritualized and complex setting. Fighting and battles were more a choreographic display rather than a struggle. Armies faced each other for hours at a safe distance, exhibiting their warrior’s fierce body-paintings and gear, hurling, and shouting abuse. Display was very important as forces were measured in the course of this process without any bloodshed. Eventually, warriors might step forward and throw projectiles that harmed one opponent. Should something come out of balance then fighting occurred. Hostilities tended to stop when anyone was wounded or killed.

See also: Social Violence and War.

World History

World History