Between CE 600 and 800 settled communities of mixed farmers and herders appeared along the western and southern fringes of the Okavango and Chobe Rivers at sites such as Divuyu and Serondella, the southeastern margins of the Makgadikgadi at Kaishe, and in the hardveld of eastern and southern Botswana. Studies of cave sediments in the Tsodilo Hills, along with changes in prehistoric site distributions in central and eastern Botswana over the past 2000 years, suggest that climatic conditions were wetter during the last half of the first millennium CE. While agropastoral communities had considerable overlap with indigenous hunters and gatherers in their use of wild plants and animals, water points, firewood, and other natural resources, they also introduced more intensive systems of land use as fields were cleared for sorghum, millet, cow peas, and a variety of other crops. More regulated systems of land rights were also needed to manage growing herds of cattle, goats, and sheep, with their increased labor, grazing, and water demands.

Cattle Wealth and Early Chiefdoms in Eastern Botswana: CE 700-1000

Between approximately CE 600 and 800 most settlements were small, mixed farming communities that combined animal husbandry and agriculture with a significant input from game and wild plants. Ceramic styles link these communities culturally to settlements known as Zhizo in Zimbabwe. Local distinctions in ceramic style, however, suggest they were a separate facies known as Taukome. By CE 700 domestic herds were large enough to leave an easily recognizable imprint on village layout in the form of centralized deposits of unburned and vitrified dung, surrounded by houses constructed of pole and a mixture of dung and mud known as daga. This pattern recurs widely across southern Africa and is known, as the Central Cattle Pattern (CCP). Over the next 500 years, herds continued to prosper and grow, producing dung deposits over 2 m deep and 60 m in diameter in the centers of some villages. These animals provided the economic capital that permitted social and political differentiation between CE 900 and 1100. Increased social stratification based upon differential holdings of cattle and small stock is reflected in regional settlement patterns as large, long-term settlements such as Toutswemogala (Figure 3) and Bosutswe were surrounded by smaller, more ephemeral satellite communities whose locations shifted when fertile land, firewood, and other productive resources were exhausted. In concert with the increasing scale of political centralization and emerging chiefly authority exercised on a regional level, as reflected in these regional changes in settlement structure, ceramic assemblages become more standardized in form and decoration and are known as the Toutswe tradition (see Africa, South: Herders, Farmers, and Metallurgists of South Africa).

Trade in Specularite and Social Differentiation in Northwestern Botswana

Social differentiation based upon intensification of commodity production and wealth accumulation was also occurring at the Tsodilo Hills in northwestern Botswana (Figure 4a And 4b) where intensive spec-ularite mining took off between CE 800 and 1100. Control of the specularite mines at Tsodilo enabled

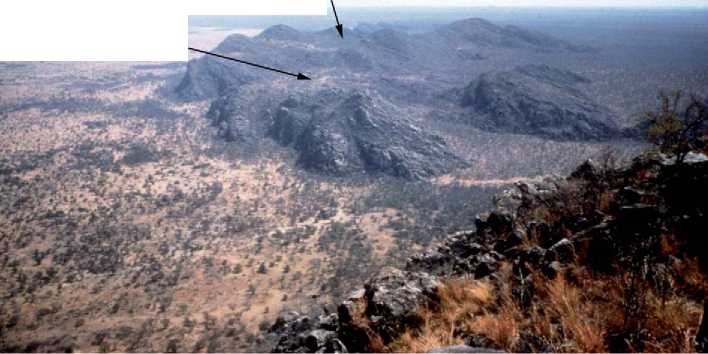

Figure 3 Aerial view of Toutswemogala showing the characteristic Cenchrus-covered midden that commonly developed in association with the animal kraals at deeply stratified Early Iron Age settlements in the eastern Kalahari. A smaller Cenchrus midden can be seen at the base of the hill. © 2008 Dr. James Denbow. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Divuyu

Nqoma

1000m 500m 0

10m 20m

Location of Iron Age sites in the Tsodilo Hills

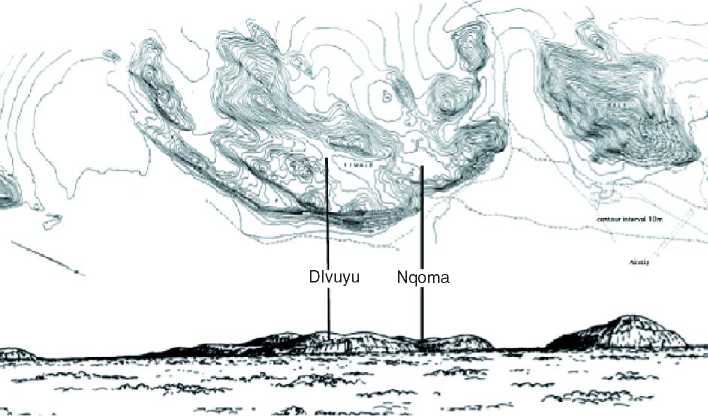

Figure 4 (a) A view of the ‘female’ hill at Tsodilo taken from the top of the ‘male’ hill showing the locations of Divuyu and Nqoma. (b) Topographic map of the Tsodilo Hills showing the locations of Divuyu and Nqoma. © 2008 Dr. James Denbow. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

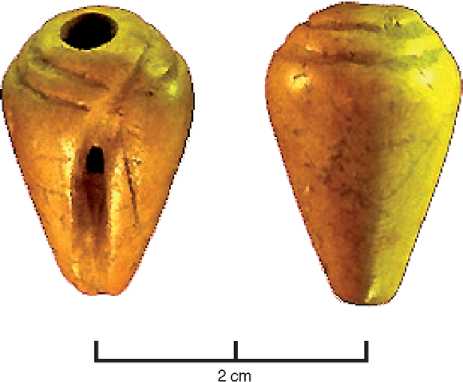

The Iron Age occupants at Nqoma to procure unparalleled quantities of iron and copper jewelry. Even glass beads, cowry, and conus shells from the east coast reached the site, making it the most distant inland entrepcit in eastern and southern Africa to have obtained luxury goods from the Indian Ocean trade in the first millennium (Figure 5). Finds of Nqoma style ceramics in the lower levels of Bosutswe suggest that at least some of these luxury goods were directed westward through emerging Toutswe chiefdoms rather than following routes along the Zambezi River. By the beginning of the second millennium, however, specularite sources in eastern Botswana may have replaced those of Nqoma, leading to an attenuation of these trans-Kalahari connections. Perhaps in consequence, Nqoma was abandoned as an elite settlement around CE 1100.

East Coast Trade and Early Chiefdoms in East-Central Botswana: CE 1000-1200

Glass beads, marine shells, and even chickens imported from the east coast begin to appear in small numbers after CE 800, but apart from the differential distribution of livestock holdings there is little other material evidence for social stratification other than a tendency for the longer-term elite settlements to be established on rocky hilltops. Whether

Figure 5 An eleventh century ivory copy of a Conus shell bead recovered from the excavations at Nqoma. Nqoma, more than 1500 km from the coast, is the most distant interior settlement so far known to have been able to import luxury items such as glass beads and cowry shells from the Indian Ocean. © 2008 Dr. James Denbow. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

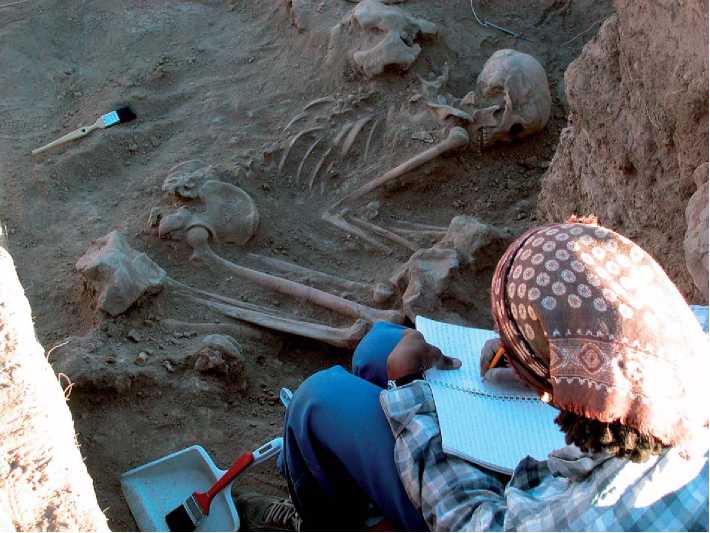

Rocky hilltops were chosen for defensive purposes, or for their symbolic associations with power and rainmaking, or a combination of both, is not known. Caches of glass beads and other status goods found at small sites such as Kgaswe indicate That access to luxury goods was not restricted to the elite on hilltop settlements and suggest that status differentiation was more fluid than it was to become later. Although more than 60 Toutswe period burials have been excavated, none has been found with distinctively rich grave goods that would attest to more developed class distinctions, such as those that make their appearance after CE 1200 (Figure 6).

The presence of central animal kraals (a term now widely used in southern Africa to denote animal pens or byres) at all sites - from the smallest to the largest - during the Toutswe period contrasts with what is found after CE 1200 when only smaller sites continue to be organized according to the CCP. Kraals disappear from elite centers such as Bosutswe, suggesting that an important change in herd management had occurred, with animals being shifted from high-status locations to smaller, commoner settlements. Whether this was in response to ecological difficulties brought about by overgrazing around large centers, or it represents a symbolic shift associated with the establishment of more rigid social hierarchies and class differentiation, is presently unclear. But there is no doubt that new spatial and

Figure 6 Toutswe burial from Bosutswe. Analysis of the skeletal material from Bosutswe indicates a population with better nutritional health than that from Mapungubwe at the same time period. © 2008 Dr. James Denbow. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Bosutswe

Bronze bangle with glass bead Gold bangle

Figure 7 The site of Bosutswe on the eastern edge of the Kalahari. The large mound in the center of the site is formed from the remains of substantial elite houses that date to the period after CE 1200 when most of the commoner Toutswe population was moved off the hilltop. © 2008 Dr. James Denbow. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

2 cm

Figure 8 The elite at Bosutswe used metal jewelry to index their social status. While they were able to acquire small quantities of gold, they were not powerful enough to compete with the elite at Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe for this commodity. In consequence, they turned to the use of high-tin bronze bangles that, if kept polished, mimicked the appearance of gold. © 2008 Dr. James Denbow. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Material coordinates were mapped onto social distinctions and evidence from Bosutswe indicates that the elite now lived alone on the hilltop, spatially separated from their subordinates (Figure 7). They ate from distinctively decorated ceramics patterned after those from Mapungubwe and known as Lose ware, and differentiated themselves in other ways through the wearing of quantities of glass beads, copper and bronze jewelry, and cloth apparel (Figure 8). Metal production, rainmaking, trade in specularite, and other activities imbued with ritual and economic significance become more centralized at elite centers at this time (see Social Inequality, Development of).

World History

World History