West, General der Panzertruppen Leo Geyr von Schweppenburg.1 It is hard to think of a worse arrangement for someone who was used to not only dealing directly with Hitler, but who also had nothing in common with two 'old guards', aristocratic officers whose approach was quite different to that of Rommel. Their differences would come to a head with their respective opinions about the deployment of the Panzer divisions.

Following standard German tactical doctrine, both Rundstedt and Schweppenburg wanted to deploy the Panzer divisions inland, with the aim of concentrating them in a massive counterattack against the Allied forces once the 'centre of gravity' of their effort had been identified. This was the classical German flexible defence doctrine that emphasized concentration of forces, movement and manoeuvre over the battle of attrition based around a rigid, static defence line. This was not a view that Rommel agreed with. Based upon his own experiences, and the failure of the German

Counterattack against the Allied landings at Anzio in Italy, he came to the

As commander of Heeresgruppe B Rommel was responsible for the entire of north-west Europe but, in spite of the large number of units under command, he kept up his habit of frequently inspecting his formations. (HITM)

Conclusion that overwhelming Allied air power (as he experienced first hand in North Africa) would deny the Germans those movement and manoeuvre capabilities that were the basic requirements of flexible defence. He proposed a similar defensive pattern to that used at El Alamein: a fixed, prepared defence line strengthened by fortifications and obstacles intended to repulse the enemy assault. Mobile forces were held back to deal promptly with any breakthrough in order to re-establish the defensive line. With the Panzer divisions held close to the landing beaches, swift counterattacks could be launched before the enemy could start its build-up, like at Anzio. Thus, even small-scale operations could prove effective and, by avoiding large-scale movements and concentration of forces, the effects of enemy air superiority could be reduced. Therefore Rommel wanted to deploy the

Panzer divisions close to the most threatened landing beaches, namely those in the Pas de Calais and Normandy, ready to counterattack immediately after the Allied

Troops started their landings,

While their forces were still weak and disorganized and before a build-up race could be started.

By counterattacking within the first 24 hours after the invasion, Rommel hoped to prevent the creation of a major Allied beachhead and from

Here thwart the enemy plans for the invasion. The ultimate solution was an unsatisfactory compromise. Rommel was allowed to deploy three divisions out of ten, which were located between Amiens and Caen (with only one able to counterattack on 6 June, the day of the Allied landings in Normandy); all the others remained as a general reserve at the disposal of Oberbefehlshaber West, though their employment required Hitler's authorization.

Rommel's solution has been often praised as the one that might have helped the Germans to win the battle for Normandy. However, at a closer look it had significant flaws. As the German counterattack at Mortain in August 1944 proves, even in the summer of 1944 the Germans still possessed the capability to concentrate their forces and manoeuvre against the Allies, even though they enjoyed the advantages of full mobility and air superiority over the battlefield. The failed counterattack launched by 21. Panzer-Division against the British beachheads on 6 June 1944 also shows that Rommel's plan for immediate counterattacks against the enemy landings was difficult to put into practice. Given the state of confusion that reigned on the German side in the first hours of the invasion owing to the lack of information, it was hard for the commanders on the ground to assess the situation properly and react

During the battle for Normandy the Germans deployed a large number of armoured and mechanized units, but were never able to concentrate them into a single, decisive counterattack against the Allied bridgehead. Shown here is a self-propelled Sturmgeschutz III, also used as a tank-hunter. (HITM)

A column of Panzergrenadiere from 1. SS-Panzer-Division 'Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler, his personal bodyguard. This division, and many others, would be kept close to the Calais area until late July-August 1944. In the foreground is a SdKfz 250/1 armoured personnel carrier. (HITM)

One of the results of the German doctrine, which favoured manoeuvre over firepower, was the insufficient development of artillery. A solution was found in the innovative use of rocket launchers called Nebelwerfer (smoke throwers), which were used to a large extent in Normandy. (HITM)

Accordingly. Generalmajor Edgar Feuchtinger, commander of the rebuilt 21. Panzer-Division (the only one close to the coasts of Normandy), launched his attack at first against the British airborne bridgeheads and only turned against the beachheads later on, with the result that the feeble and uncoordinated German attacks achieved nothing. It would have required a Rommel, or indeed more than one, to carry out this plan in a purposeful way. However, by the spring and summer of 1944 the German Army was running short of skilled and experienced field commanders. The real mistake made by the German commanders in Normandy, including Rommel, was to commit their reserves in a piecemeal way. They did this for two reasons; first in an attempt to secure the front line and prevent the Allies from breaking out of the

Beachheads; second because many, with Rommel amongst them, believed firmly that Normandy was not the 'centre of gravity' of the Allied invasion. This mistake also arose as a consequence of the lack of combat-worthy front-line units, the Panzer divisions being the only ones available, and out of the 'yield not one inch of ground' state of mind that now dominated the German Army. Only after the Allied forces broke through the Normandy beachhead did the Germans attempt to regain the initiative through the use of mobility and manoeuvre. However, by this point it was too late to make

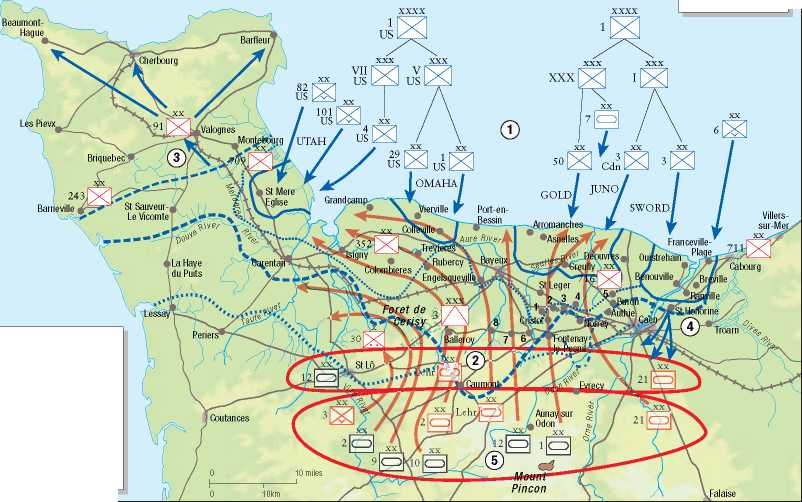

Counterattack on D-Day

Rommel's plan to counteract the Allied landings was to deploy the Panzer divisions close to the invasion beaches, ready to counterattack immediately after the landings. On 6 June 1944 only the 21. Panzer-Division was close to the Allied landing

In Normandy, and its counterattacks started only in mid-morning and were uncoordinated. In the afternoon Panzer-Regiment 22 attacked towards the Periers Ridge supported by the infantry of Panzergrenadier-Regiment 192; at Bieville II/Panzer-Regiment 22 lost eight PzKpfw IV tanks to anti-tank guns, while the other battalion had no better luck as it ran into British armour. At dusk the attack was called off, without any breakthrough being achieved.

A Luftwaffe gunner Loading an 88mm Flak 36/37, part of III Flak Korps. This gun, like those in North Africa, was employed in Normandy in the dual role of anti-aircraft and anti-tank and soon acquired a sinister reputation amongst Allied tank crews. (HITM)

A German anti-tank rocket launcher, based on the American 'bazooka, called the Panzerschrek (tank terror) in Normandy. By late 1943 the widespread introduction of portable anti-tank rocket launchers improved the capability of the German infantry to deal with enemy armour, though it could not close the gap between German tank production and that of the Allies. (HITM)

Good their mistakes. The piecemeal commitment of German mechanized reserves in Normandy led to a battle of attrition, different from those fought by Rommel in North Africa, and one that the Germans could not win. The large-scale counterattack against the Normandy beachhead planned in June-July by Panzergruppe West never materialized, simply because all the forces needed were already committed here and there on the battlefront to prevent enemy breakouts.

One can easily imagine how Rommel might have led that counterattack, but the reality was quite different. During the 40-odd days he was active on the Western Front, Rommel visited the front line often to meet unit commanders at every level, giving orders, talking to them and making suggestions. This time there were no offensives or dashes forwards for him to lead, and eventually, as the Allied noticed, it was difficult to make out Rommel's mark on the battle of Normandy. Just as the Normandy of

1944 was something completely different from the North Africa of 1941-42, so the Rommel of 1944 was a different man. The situation had changed, and he was certainly concerned about other matters when, on 17 July 1944, strafing British fighter-bombers hit his staff car in Normandy, putting an end to his military career. The wounded Rommel would not return to the front before his suicide three months later. The military commander was dead, but the myth was about to be created.

A group of Fallschirmjager and a Sturmgeschutz in the Cotentin Peninsula, June 1944. The failure to prevent the seizure of Cherbourg by American forces was the first signal of how desperate the situation in Normandy was. (HITM)

World History

World History

![Road to Huertgen Forest In Hell [Illustrated Edition]](/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432477693_1428700369_00344902_medium.jpeg)