Islands. Even the small group privy to the secret could not rely upon the atomic weapon coming in time or being effective enough to preclude the necessity of a seaborne invasion, so it was still necessary to keep the Soviet Union in line.

A further handicap, of lesser though not negligible significance, was that Roosevelt had public opinion to contend with (as of course did Churchill) while Stalin did not, and once the Americans and the Russians became allies, it was necessary to persuade American opinion that the Russians were no longer the Communist bogey-men of earlier years but Russian patriots only concerned with the defence of their fatherland. Pro-Soviet propaganda was thus given a free hand and prospered by it to the extent that Roosevelt himself became its victim, in that he did not perceive fully that the Russians made no distinction between the military and the political and that the war they were fighting, defensive though it might be in immediate origin, was nothing more in their eyes than another round in the inevitable conflict between the 'Communist’ and the 'imperialist’ halves of the world. Nor, believing this, could the Russians take seriously the Americans’ protestations of political neutrality in respect of other countries. When any military decision was taken which did not suit their book, they assumed that it showed that their allies were still hankering after a compromise peace and had no real interest in relieving the Russian front.

The relations between Roosevelt and his principal allies were thus curiously paradoxical. Outwardly the intimacy was far greater between the Americans and the British than between either and the Russians. Their service and supply personnel worked in relations of mutual confidence and at many levels; the personal rapport that developed between Roosevelt and Churchill through personal encounters and continuous correspondence was paralleled lower down. The British had no hesitation about admitting their indebtedness to the Americans or their hopes that the partnership would be prolonged into the peace. They were prepared, in order to get the necessary results, to transfer to North America the work on atomic weapons which had made its first crucial strides on British soil.

On the Russian side everything was different. Help was asked for, and even demanded, but no accounting was given and no information as to Russia’s own plans and resources was ever proffered; the Russian people were insulated as far as possible from the knowledge of the American (and British) contributions to their defence. Roosevelt and Stalin met only twice. Nevertheless, it was the American belief that fundamentally Americans and Russians were fighting for the same ends and looking forward to the same kind of post-war world while the British were interested in objectives which were alien or antipathetic to American opinion. It was for a long time Roosevelt’s clear desire not to do anything which could suggest that he and Churchill were making plans from which Stalin was excluded, and his clear belief that Stalin would be open to the kind of amicable persuasion that had been so successful an instrument of his domestic policy.

Roosevelt’s illusions

The principal reasons why Roosevelt cherished such illusions —illusions encouraged by his highly unsuitable and poorly qualified ambassador in Moscow, Joseph E. Davies —could be found in three very abstract ideas which figured largely in Roosevelt’s thinking but which had quite a different meaning from the ones that the Russians attached to them. In the first place he believed that the British — and Churchill in particular —were 'imperialist’ and that both the Russians and the Americans were 'anti-imperialist’. That is to say he was worried lest Churchill try to influence the grand strategy of the war in ways which would be conducive to the defence of Britain’s imperial possessions, or the recovery of those that had been lost, to the detriment of a more rapid overall victory. He did not perceive that the Russians attached quite another meaning to anti-imperialism and were by no means averse to using their power to spread the bounds of the Communist empire. In the second place, Roosevelt believed that Americans and Russians both stood for 'democratic’ government while the British hankered after preserving or restoring monarchies and other non-democratic forms of government for instance in Italy and Greece. It was only towards the very end of his life, when Russian intentions in Poland could no longer be overlooked, that Roosevelt came to understand the interpretation that Stalin put upon democracy. Finally, Roosevelt shared the antipathy of his former leader Woodrow Wilson for the notion of the balance of power, imagining that the post-war world could be managed by an amalgam of the wartime Grand Alliance with the principle of national self-determination and the equality of states, the whole given institutional form in what became the United Nations Organization. He was thus averse to any consideration in advance of how the peace settlement could be assured of sufficient support against future revisionism. And this again separated him from Churchill, since, while the Russians could accept with equanimity Roosevelt’s assumption that once victory was won, Amt*ric! in forces would rapidly be withdrawn from Europe, Churchill had to consider how British security could be safeguarded in such circumstances.

The practical consequences of the last of these attitudes revealed them. selves particularly in respect of two other countries, China and F'rance. Roosevelt believed that once Japan had been defeated China would become a great and friendly [X)wer deserving of a permanent seat in the Security Council of the United Nations, and was influenced in his assessment of the Asian scene by Chinese opinion. Churchill was much more sceptical about the Chinese regime and its future. He, again, was very conscious of Britain’s need for a restored and strengthened France as an essential component of the new Europe. Having early decided that General de Gaulle and his movement was the most likely vehicle for France’s recovery of her independence, Churchill gave the de Gaulle movement a considerable degree of material and moral support. Roosevelt on the other hand first took longer to despair of the Vichy government and then, after the liberation of North Africa, did his best to avoid handing over the political reins there to de Gaulle. Later on he tried to avoid installing de Gaulle’s authority in France itself and to plan for some form of temporary Allied military occupation until the French could choo. se their own form of government. At both stages the strength of de Gaulle’s position was such that Roosevelt’s objectives were frustrated. Finally, Roosevelt and Stalin were at one in minimizing France’s importance and in being unwilling to allow the de Gaulle government to share in the occupation and control of Germany and it was left to Churchill to make the running in favour of France’s claims —this time successfully, partly perhaps because of a temporary Franco-Russian rapprochement.

Fundamentally —though the personal antipathy of Roosevelt and of his narrow and limited secretary of state, Cordell Hull, for de Gaulle had something to do with it — the point was that Roosevelt believed that France’s major role in world politics was at an end and was indifferent to France’s claims. He was also hostile to the continuation of France’s overseas empire and his successor, in conjunction with the Chinese, was able to hold up the re-imposition of French authority in Indo-China after the Japanese defeat. Churchill did not hold these opinions but realized the extent to which Great Britain depended upon American goodwill and could never afford ultimately to defy the Americans for the sake of the French. Thus while the British were in fact doing what they could for de'Gaulle, they gave the French the impression that they were wholly committed to the same

Attitude as the Americans —and this helped to foster de Gaulle’s strong feelings about the 'Anglo-Saxons’.

For although Roosevelt played down the role of power in the post-war world so long as the war lasted, he was very ready to use American power to make sure that he got his way. But this realism could go the other way as well. His desire to see the Russians enter the war against Japan gave them the means of extracting concessions from the Americans at China’s expense. In fact the Americans did not need Russian aid: the atomic bomb was enough. And the Russians did not need bribing to enter the war in the Far East since they had their own territorial and political aims to fulfil, nor did they require anyone’s permission to do so. For the Russians it was never the same war as the one Roosevelt thought he was fighting.

But it would be a mistake to try to view the history of wartime diplomacy and policy-making in terms of 'Cold War’ origins as is sometimes done. The lines of conflict between the Soviet regime and the West had been defined between 1917 and 1919 and had not changed in essentials. What happened during the period between 1941 and 1945 was a partial suspension of the conflict because of the mortal danger in which the Soviet Union found itself and because of the greater immediacy for the Western powers of the threat from Nazi Germany. For most of the war Roosevelt like his allies had to concentrate on the planning and winning of the campaigns against the immediate enemy. It is only in retrospect that one can see how the unresolved issues in the Soviet Union’s relations with the rest of the world had their effects upon what was done.

The Americans were slower than the British in pledging support to the Soviet Union after Hitler’s attack in June 1941 and shared British scepticism as to the ability of the Russians to carry out a prolonged resistance. But the visit of Roosevelt’s confidant Harry Hopkins to Moscow set in train the proce. ss of supplying the Russians out of the now rapidly increasing war production of American industry.

The main issue was the Russian demand for a 'seajnd front’ against Germany: that is to say a landing as soon as po. ssible on the mainland of Europe by Anglo-American forces so as to draw off part of the German land forces from the Ru. ssian front. This pre. ssure began with a letter from Stalin to Churchill on 18th July 1941 and it was against Great Britain that the main pre. ssure was directed. It was clear, however, that any such landings would have to involve American forces and the American military were indeed amvinced that this strategy would be the most effective way of defeating Germany quite irrespective of Russian needs. They were suspicious that Churchill’s unwillingness to press forward with this policy and his interest in alternatives were due to an excessive concern about possible losses, and to a nostalgia for the 'indirect approach’ exemplified in the Gallipoli operation of the First World War. On the other hand, in contrast to the Russians, the Americans were fully aware of the immense difficulties of making an amphibious assault on a heavily defended coastline and were unwilling to attempt such a thing until all the technical preparations had been made. Meanwhile they came round to relying for the time being upon the strategic air offensive against Germany itself and upon the Mediterranean operations which began in November 1942.

Uncertain alliance

The degree to which the Russian war was still considered as something separate is illustrated by the absence of the Russians from the meeting between Roosevelt and Churchill at Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, in August 1941 at which the policy to be adopted towards Japan was discussed and at which the Atlantic Charter, with its promise of joint action after the war in the setting up of a new and more peaceful world system was promulgated. It remained the case that relations with Japan with which Great Britain and the United States were at war from December 1941 was. something from which the Russians deliberately held aloof, since they were unwilling to add Japan to the number of their enemies before they came in to seize their share of the spoils of Japan’s defeat in August 1945. The Grand Alliance which was embodied in the United Nations Declaration of 1st January 1942 was thus of necessity ambiguous about the enemy against which it was directed.

Subsequently relations between Roosevelt and his principal two allies were for some time carried on on a triangular basis by means of bilateral discussions. And this may partly explain the ambiguities about the promises to invade Europe made in the summer of 1942. When it came to the North Africa landings which the Russians had perforce to accept as a substitute, the {X)litical issues of the future began to show themselves. In North Africa, the Americans took the lead, first in making a deal with the Vichy commander Admiral Dar-lan, and subsequently in endeavouring to promote General Giraud in preference to General de Gaulle and who had the support of the British and of the French resistance movement including the Communist elements and so might be exjxicted to commend himself to the Ru. ssians.

An attempt was made to clear up the political and military difficulties in the

Mediterranean theatre in a meeting between Roosevelt and Churchill at Casablanca in January 1943. Stalin, who was invited, declared himself unable to leave Russia. It was here that the principle of 'unconditional surrender’ was agreed upon; and Stalin later approved it.

In fact the phrase was not a very meaningful one since the important thing was the decisions that would be taken in handling the problems of the liberated territories and ultimately those of Germany, Italy, and Japan. Roosevelt was opposed in theory to the division of spheres of influence between the victors; but in practice there was no real alternative. The Soviet Union did not take part in the negotiations leading to the surrender of Italy, and its ultimate reappearance in October 1943 as an Allied co-belligerent; and the Russians were given after protest only a formal share in the running of Italian affairs. Events were to follow the same course in Greece where Great Britain, by agreement with the Russians, took the lead; and on their side, the Russians were ultimately to exclude all Western influence from the rest of Eastern Europe.

This was the reality against which one had to measure the work of the tripartite conferences which were the focus of the last phase of the conflict: the meeting of the three foreign ministers at Moscow in October 1943 and between the leaders themselves at Tehran in November-Decem-ber 1943 and Yalta in February 1945. The Americans were too concerned to secure Russian co-operation in the setting up of a world security organization which was agreed upon in principle at the Moscow conference and in getting agreement on general principles for co-operation in the handling of a defeated Germany to worry overmuch about the precise nature of the political settlements arrived at. It was the loose diplomacy of this period and the refusal of the Americans to entertain the doubts which Churchill now began to express about Russia’s future intentions, or to let the military operations take such doubts into account, that were typical of these final stages of the war jn Europe. And it was in these circumstances that the ambiguous agreement over Berlin and access to it was allowed to go forward with all the future problems that this entailed.

But it would be an error to think that had Roosevelt lived there would have been a very different attitude towards relations with Russia from that which developed under President Truman. Towards the end of his life, the Russians’ behaviour, particularly in respect of Poland, was already causing Roosevelt deep anxiety and had he lived the same decisions as fell to be made by Truman would almost certainly have been made by him.

Poland's Agony

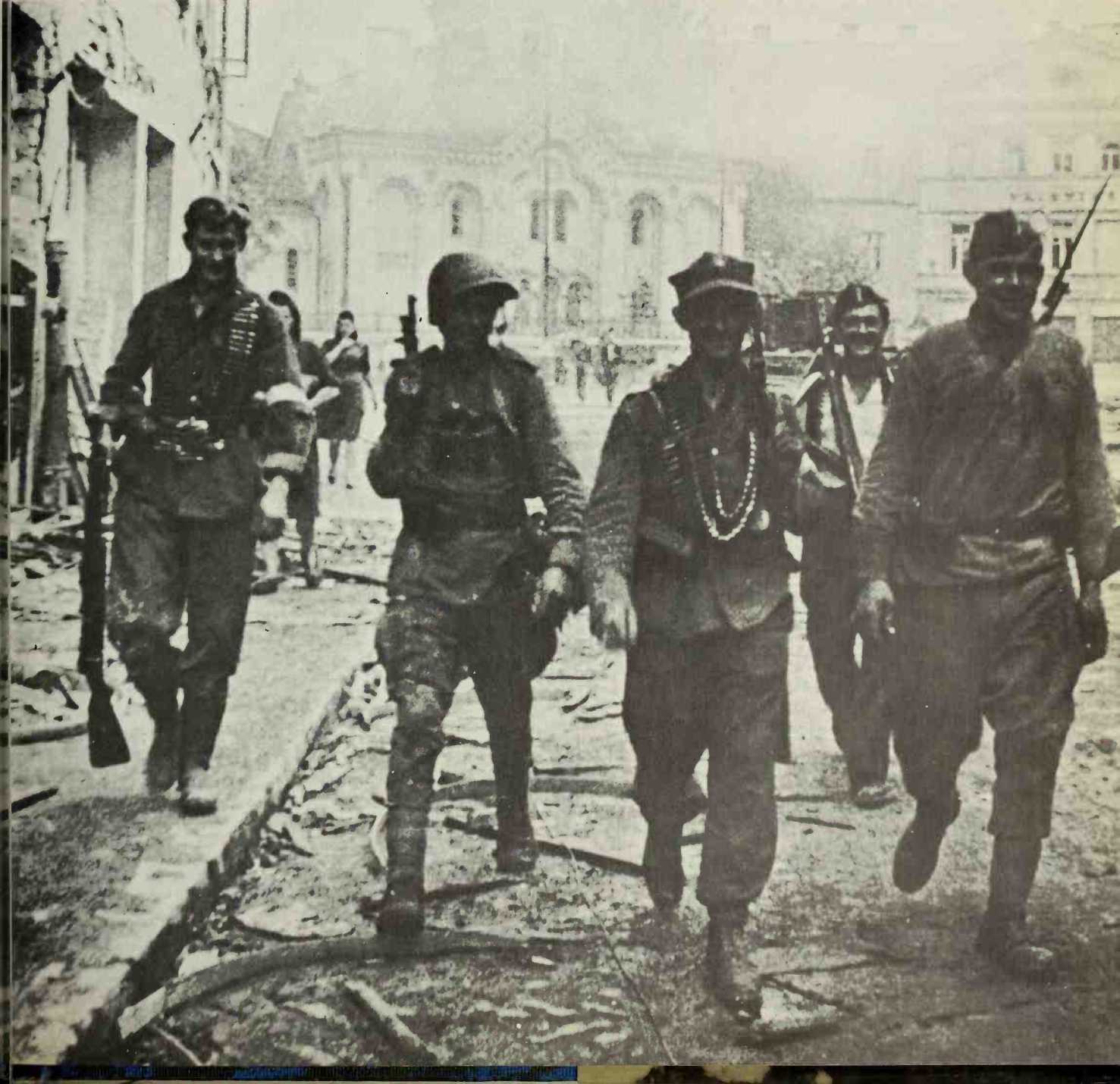

Meeting at Tehran, in late November 1943, what should be the frontiers of the new Members of the Poliak IInmo Army with

The Big Three, Stalin, Roosevelt, and Polish state, and what government should Soviet troops in Sandomierz after the

Churchill, tackled one of the great political take charge of it after the war. In two capture of the town by the lied Army

Problems of the Second World War, that of after-dinner talks the Big Three amicably

Poland. In reality there were two problems: settled the first problem. Poland’s frontier

In the east was to be the so-called Curzon Line with some minor corrections in favour of Poland. For the territory in the east lost to the USSR Poland would get generous compensation at Germany’s expense: much of East Prussia, Danzig, Pomerania, and Silesia as far west as the Oder and Neisse rivers. On the other problem the Big Three made less progress. They agreed that they wanted post-war Poland to be strong, independent, democratic, and friendly to the Soviet Union. Their conceptions of the kind of government best adapted to secure that end differed, but they did not want to spoil the harmony of the conference by airing their differences at that stage.

Great Britain and the United States recognized the Polish government-in-exile in London and the leaders of the two countries wanted it to be the basis of the future government of Poland. Churchill evidently thought that he could, in exchange for his backing of the Curzon Line, get Stalin to accept the London Poles as the dominant element of the new government. This was only possible if the London Poles quickly accepted the frontiers laid down at Tehran and made some concessions of a minor kind. Though he failed in his aim, Churchill remained convinced to the end that he could and would have succeeded if the Polish politicians had been realistic and co-operative.

In his dealings with the exile government Churchill could not expect any help from the US President; quite the opposite. Roosevelt made it plain at Tehran that he had to conceal his acceptance of the Curzon Line until after the presidential election of November 1944.

He was extremely worried that the large Polish minority in America which had voted for him solidly in the past, might in anger switch to the Republicans and possibly cause his defeat. While the governments of Great Britain and the USSR, without disclosing the Big Three agreement on the subject, soon afterwards openly declared that the Curzon Line was a fair basis for a settlement, Roosevelt remained publicly uncommitted, and indeed managed to create the impression that he kept an open mind on the issue. The official American line was that frontiers ought to be settle<l by agreement between the countries concerned or, failing such agreement, at the peace conference, as part of a general post-war settlement. Admittedly hints were dropped to the Polish government in London that the Americans could not support them against Churchill and that they ought to come to terms with the Russians. But when Roosevelt finally agreed to talk to the Polish Premier in Washington (in June 1944) he evaded answering the question where he stood on the Curzon Line issue.

This ambiguous attitude of Roosevelt gave the London Poles false hope that he might perhaps support them at the peace conference, and tended to stiffen their opposition to a more immediate settlement.

Massacre at Katyn

The USSR had broken off diplomatic relations with the exile government in April 1943, taking strong offence at the latter’s demand for an International Red Cross investigation into the massacre of Polish army officers at Katyn. (In April 1943 German troops in occupied Russia claimed to have found a mass grave in Katyn Wood near Smolensk, in which the bodies of several thousand Polish army officers, who had been taken prisoner by the Russians in 1939, were buried.) As one necessary condition for resuming relations Stalin demanded a public endorsement of the Soviet claim that it had been a German atrocity —an unpalatable demand for the Poles who strongly suspected the Russians. Further, Stalin wanted at least the most rabid anti-Soviet individuals to leave the London government—a wish for which Churchill and Roosevelt had strong sympathy. Stalin alleged that the London-controlled resistance movement did not fight the Germans enough and that it sometimes liquidated Soviet partisans. He also complained of the unrepresentative character of the exile government, and mentioned Polish 'democratic organizations’ in Great Britain, the USA, the USSR, and the underground in Poland, which were not included in the London coalition. As if to underline the Soviet claim, a National Council of the Homeland was set up secretly in Warsaw by the Communist Polish Workers’ Party at the end of 1943. It was said to unite various progressive groups outside the London camp, and the military units under its control formed the People’s Army. But it was the acceptance of the Curzon Line which was the paramount condition for resuming relations. Churchill at any rate was confident that the minor obstacles could all be overcome once the stumbling block which the Curzon Line represented was out of the way.

After returning to England from Tehran Eden and then Churchill personally got to work on the London Poles. They wanted the Poles to accept the Curzc>n Line (as Churchill once put it), not grudgingly, but with enthusiasm, as a just and reasonable frontier, which would be the foundation of lasting Polish-Soviet friendship. But to the great chagrin of the British leaders the Poles would not do it, though they resorted to evasions and delays rather than reject the demand outright. They queried details of the new frontiers in the east and the west. They suggested resuming diplomatic relations with the Soviet government before negotiating frontiers. They proposed a temporary Soviet occupation of the prewar eastern borderland of Poland leaving the permanent frontier to be settled after the war. They insisted on talks with Roosevelt before deciding, and so on. They readily agreed to intensify partisan and sabotage op>erations against the Germans by the Home Army —the military resistance movement under their control —and to get them to collaborate with the advancing Red Army. The one Soviet demand they did reject flatly was the purge of anti-Soviet politicians, indignantly branding it as an unwarranted interference with a sovereign government. More than six months of continuous British pressure did not succeed in inducing the London Poles seriously to try and come to terms with the Russians.

The chief architect and outstanding personality of the exile government, who had combined the offices of Prime Minister and Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Armed Forces, was General Wladyslaw Sikorski. Churchill greatly respected him as a statesman and a realist, and was deeply sorry when he died in a plane crash off Gibraltar in July 1943. Sikorski was succeeded as Prime Minister by the Peasant Party leader Stanislaw Mikolajezyk whose authority was not of the same order as Sikorski’s. Mikolajezyk stood to the left of most of his cabinet colleagues and believed in the need to reach accommodation with the Soviet Union. But he doubted his ability to persuade them to accept any serious political sacriflees. His opponents, who feared and distrusted him, included two ministers (General Kukiel and Kot) and Sikorski’s successor as commander-inchief, General Kazimierz Sosnkowski. They were the men whom the Russians wanted particularly to see dropped from the government.

World History

World History

![The Battle of Britain [History of the Second World War 9]](/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432582012_1425485761_part-9.jpeg)