It can be easily imagined that the motte-and-bailey castle was a rather primitive dwelling place and a rather weak and rudimentary fortification. Militarily its main inconvenience was that it was made of wood, the material most accessible and most easily worked, but also the most flammable. Obviously buildings, obstacles and fortifications made of earthwork and wood were perishable. When intended to be permanent works, they could not be left unattended for years, and therefore had to be constantly reviewed, maintained and renewed. For these reasons, in the 12th century some powerful and wealthy lords had all or parts of the timber work (the domus, the palisade cresting the motte, and the palisade enclosing the bailey) replaced with a stone wall known as a curtain, enceinte or chemise (French for shirt). The result was an improved version of the motte-and-bailey castle known as motte-and-stone-wall or shell-keep. This was characterized by a circular, oval or polygonal stone wall, generally with the accommodations built against its inner face, leaving an open and commodious courtyard in the center, which was accessed by a porch-like entrance. Access to the wallwalk and battlement was by means of staircases. A shell-keep was an enclosure rather than a building, and as such, its height was usually relatively low in comparison with its diameter. Shell-keeps were comparatively small, their walls being on average 2.5-3 meters thick and rising at the most to a height of 7 or 8 meters.

However, not all shell-keeps were later replacements of earlier timber works. Some of them were built not on an earlier motte but on level ground. Some at least appear to have been built within a few decades of the conquest, and shell-keeps should not be seen as a transitional form between the motte-and-bailey castle and the stone keep but rather as a part of the repertoire of Norman fortification techniques, showing their capacity for adapting themselves to all kinds of circumstances. Shell-keeps show wide variations of a common type, and form the nucleus of a high proportion of British castles, even if it is sometimes difficult to recognize them due to later additions. The Round Tower of Windsor Castle in Berkshire is an exam-

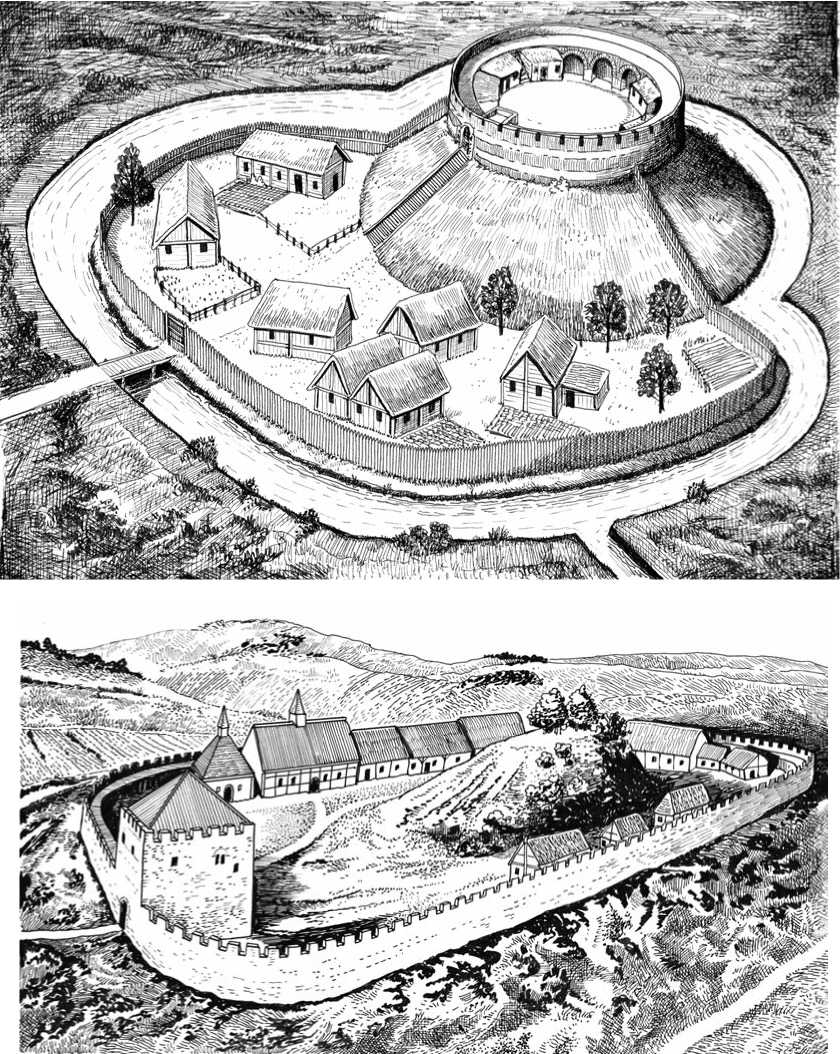

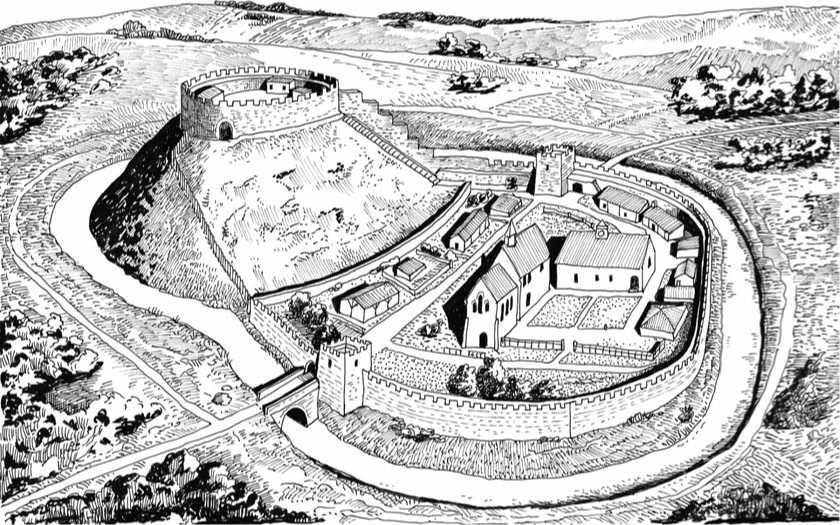

Top: Shell-keep.

Bottom: Bramber Castle, located on a steep hill above the wide, once marshy valley of the Adur River in West Sussex, is a shell-keep originating from a motte-and-bailey castle. Originally a timber castle was built on a motte (in a central position in the bailey) by a certain William De Braose in c. 1070. This was modified in c. 1100 when a gatehouse of flint and stone construction (measuring about 38 x 40 feet), an outer curtain with wallwalk and battlement, and domestic buildings and a church were built. The conjectured illustration shows how the castle might have looked in the 12th century.

Lincoln. In 1068 William the Conqueror built a wooden motte castle (replaced with a stone shell-keep castle in the 12th century) to control the townspeople.

Restormel Castle (conjectured reconstruction), located on a spur of high ground dominating the River Fowey near Lostwithiel in Cornwall, was one of the four Norman castles of Cornwall, the others being Launceston, Tintagel and Trematon. The castle of Restormel was built in c. 1100 in the typical shell-keep style by the sheriff of Cornwall, Baldwin Fitz Turcin, as replacement of an older original timber defense. The oval castle enceinte (approx. 30 feet high, 8 feet thick and 125 feet in diameter) was built on top of a 17-meter-high artificial motte. A gatehouse with drawbridge gave access to a large (now disappeared) quadrangular bailey enclosed with a stone wall, which extended on gently sloping land southwest from the motte. The impressive ruins of Restormel Castle are now administrated by English Heritage and are open to the public.

Totnes Castle, a fine example of a Norman shell-keep, was one of the first three castles to be built in Devon, in a clear attempt to tighten William’s hold over this potentially rebellious shire. The shell-keep of Totnes Castle was built in the 11th century, probably about 1100, and reconstructed in the 14th century. The castle was almost circular in plan and there were lean-to sheds and houses lining the wall, as well as a crenellated wallwalk that was 15 feet above courtyard level. The shell-keep stands on top of a large nearly circular motte nearly surrounded by a 70-feet-wide ditch. The motte is made of layers of earth, rock and clay packed down onto a natural rock mound, and it would originally have been topped by a wooden tower. The adjacent D-shaped bailey was originally enclosed by a palisade and later by a crenellated stone wall as well as by a large ditch. In the bailey there were the usual domestic buildings and a church. A stair placed along the east wall led from the bailey to the summit of the motte. The conjectured reconstruction shows Totnes Castle as it might have appeared in the 14th century. The site, now amputated of its bailey, stands in the middle of the city of Totnes. It is owned by English Heritage and is open to the public.

Ple of such a transformation. The original structure was a massive retaining wall 12 feet thick and 130 feet in diameter. Within this wall King Henry II erected another work, and in 1826 came the final neo-Gothic addition, giving the tower the appearance it has today.

There was a great concentration of motte-and-bailey castles along the Welsh border, in Pembroque and in the Midlands, whilst a high proportion of shell-keeps are to be found in the southern half of England. Good examples of shell-keeps (often with later additions) are Restormel Castle and Launceston, both in Cornwall; Totnes in Devon; Arundel and Lewes, both in Sussex; Tonbridge in Kent; Caldicot in Monmouthshire; Carisbrooke on the Isle of Wight; Bramber Castle in West Sussex; and Rothesay in Scotland.

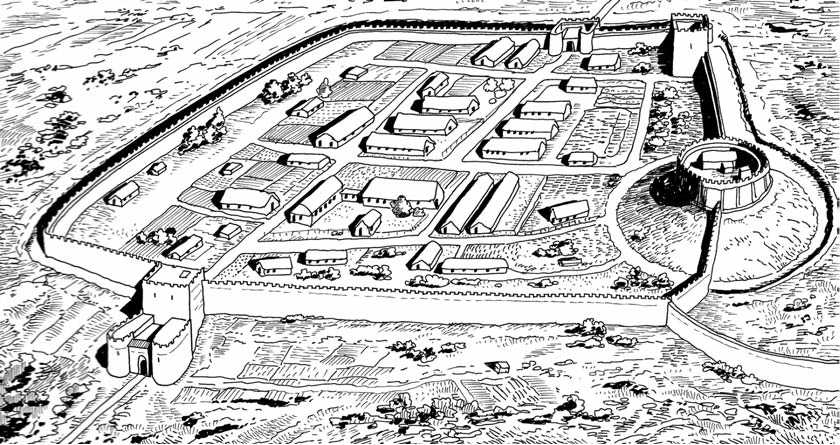

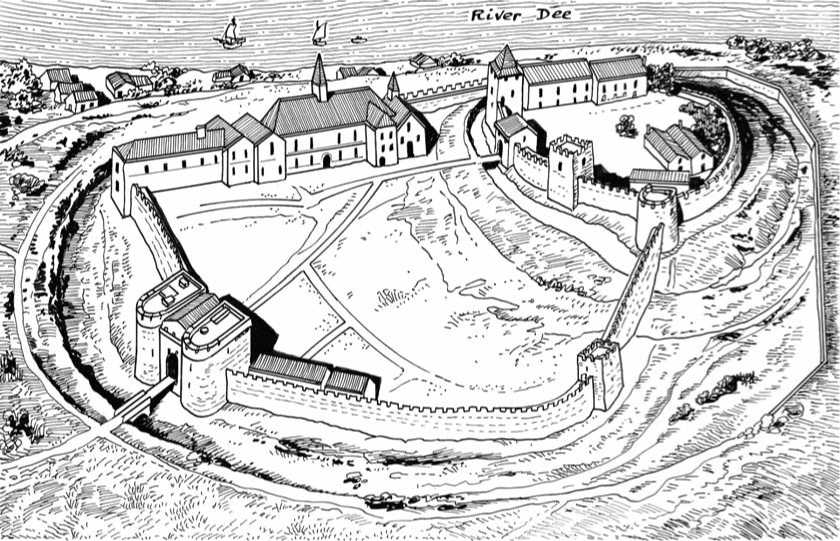

Chester Castle is located in the city center, off Castle Square in Cheshire. Chester provides a good example of a simple Norman timber castle developed into a large stone fortress. The structure originates from a Norman motte-and-bailey castle, founded by Hugh Lupus of Avranches, first earl of Chester. Standing on an eminence, it was intended to command a bridge over the River Dee. In the 12th century the wooden tower was replaced by a square stone tower, called the Flag Tower. During the same century the stone gateway to the inner bailey was built. In the 13th century, during the reign of King Henry III, the castle was enlarged. Later in the century, during the reign of Edward I, a new gateway to the outer bailey was built. This was flanked by two half-drum towers and had a drawbridge over a moat 26 feet (8 meters) deep. Further additions to the castle at this time included individual chambers for the king and queen, a new chapel and stables. Sadly all that is left of this large and important castle are fragments of the 12th-century inner bailey curtain wall, the Flag Tower and the original inner bailey gateway called the Agricola Tower. In the 18th century the remaining medieval buildings and towers were levelled to make way for a new barrack block and the Assize County Courts. The castle neoclassical buildings designed by Thomas Harrison, built between 1788 and 1813, are used today as Crown Courts and as a military museum. The site is now managed by Chester City Council and the Agricola Tower is open to the public. The illustration shows how Chester Castle might have appeared in the 13th century.

World History

World History