DE-STALINIZATION AND THE DISAPPEARING ACT

After Khrushchev’s “secret speech” denouncing Stalin in 1956, the dictator’s image was gradually removed from its place of honor in offices, public squares, and hearthsides.

It was also removed from films made during the height of his reign.

During the early 1960s, Soviet archivists produced “revised” versions of 1930s classics that expunged all views of the leader. It was relatively easy to cut out shots in which

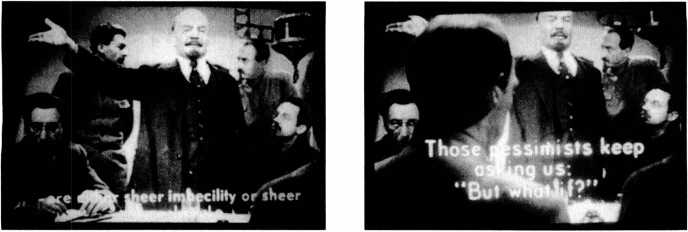

18.40, left Lenin in October, Stalin standing on the left.

18.41, right Lenin in October Stalin hidden by a Wellesian foreground supplied by special effects.

Stalin appeared and redub sound tracks to eliminate references to him. But sometimes shots could not be cut without losing story information. Therefore, optical tricks were used to cover portraits of Stalin and his henchmen with large vases of flowers or pictures of Marx and Lenin. When Stalin himself was in the shot, matte work eliminated him,

Sometimes in bizarre ways. Mikhail Romm revised his Lenin in October (1937) by blocking Stalin out with Welle-sian foreground elements, such as a head or an elbow (18.40, 18.41). See Alexander Sesonske, “Re-editing History: Lenin in October,” Sight and Sound 53, no. 1 (winter 1983/1984): 56-58.

REFERENCES

1. Quoted in “Industry: Beauty from Osaka,” Newsweek (11 October 1955): 116.

2. Quoted in Boleslaw Michalek, The Cinema of Andrzej Wajda, trans. Edward Rothert (London: Tantivy,

1973), p. 18.

3. George S. Semsel, “Interviews,” in Semsel, ed., Chinese Film: The State of the Art in the People’s Republic (New York: Praeger, 1987), p. 112.

4. Quoted in Bunny Reuben, Raj Kapoor: The Fabulous Showman (Bombay: National Film Development Corporation, 1988), p. 380.

5. Quoted in Haimanti Banerjee, Ritwik Kumar Ghatak: A Monograph (Pune: National Film Archive of India,

1985), p. 22.

6. Quoted in Robert Starn and Randal Johnson, “The Cinema of Hunger: Nelson Pereira dos Santos’ Vidas Secas," in Starn and Johnson, eds., Brazilian Cinema (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1982), p. 122.

7. Quoted in Francisco Aranda, Luis Buiiuel: A Critical Biography, trans. and ed. David Robinson (London: Seeker and Warburg, 1975), p. 185.

FURTHER READING

Babitsky, Paul, and John Rimberg. The Soviet Film Industry. New York: Praeger, 1955.

Banerjee, Haimanti. Ritwik Kumar Ghatak: A Monograph. Poona: National Film Archive of India, 1985.

Chute, David, ed. “Bollywood Rising: A Beginner’s Guide to Hindi cinema.” Film Comment 38, 3 (May/June 2002): 35-57.

Dissanayake, Wimal, and Malti Sahai. Raj Kapoor’s Films: Harmony of Discourses. New Delhi: Vikas, 1988.

Franco, Jean. The Modern Culture of Latin America: Society and the Artist. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin, 1970.

Hirano, Kyoko. Mr. Smith Goes to Tokyo: Japanese Cinema under the American Occupation 1945-1952. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992.

“Indian Cinema.” Quarterly Review of Film Studies 11, no. 3 (1989).

Michalek, Boleslaw. The Cinema of Andrzej Wajda. Trans. Edward Rothert. London: Tantivy, 1973.

Oms, Marcel. Leopoldo Torre Nilsson. Paris: Premiere Plan, 1962.

Rajadhyaksha, Ashish. Ritwik Ghatak: A Return to the Epic. Bombay: Screen Unit, 1982.

Rangoonwalla, Rionze. Guru Dutt: 1925-1965. Poona: National Film Archive of India, 1982.

Wajda, Andrzej. Double Vision: My Life in Film. Trans. Rose Medina. New York: Holt, 1989.

World History

World History