As the scene of Christ’s death and resurrection, the city of Jerusalem had long been the principal goal of Christian pilgrimage by the time that it was captured by the Saljuq Turks in 1073. The city and its shrines became the focus of the crusading movement after the recovery of the Holy Land was proclaimed by Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermont in 1095. Having been seized by the Fatimids of Egypt in 1098, Jerusalem was captured by the army of the First Crusade (1096-1099) on 15 July 1099 after a four-week siege, and became the capital of the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem until 1187, when it was lost to Saladin. The recovery of the Holy City remained a major objective of the crusading movement, but Christian rule was restored only for the short period 1229-1244.

Population

The crusader conquest destroyed or dispersed the native population of Jerusalem. When they took the city by storm, the crusaders massacred most of its Muslim and Jewish inhabitants. Although some of the native Christians who had been expelled by the Fatimid garrison now returned, they and the Frankish newcomers initially amounted to only a few hundred souls. The problem of repopulation was exacerbated by the Franks’ policy of prohibiting the settlement of Muslims and Jews in the city, in order that their presence might not pollute its holiness. If Jews or Muslims appeared in the city later, they were usually pilgrims or people who had obtained special permission to settle for business purposes (paying a tax for the favor), such as the four Jewish families mentioned by the traveler Benjamin of Tudela living opposite the citadel in the 1170s, who had worked as dyers there since the time of King Baldwin II (1118-1131).

During the first two decades of the kingdom, the city’s population was so small that only the former Christian Quarter around the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was inhabited. Baldwin I brought in Syrian Christians from Transjordan, who settled in the former Jewish Quarter. An additional initiative to repopulate the city was a law passed in 1120 exempting all foodstuffs from customs payments levied at the gates to the city. Royal privileges also granted land and houses in the city to the military orders. The result of these various initiatives was that by the 1180s the population of Jerusalem had reached some 20,000-30,000 [Prawer, The Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, p. 82]. According to the pilgrim John of Wurzburg, who stayed in the city in the early 1160s, the Latin population was predominantly of French origin, with some Italians and Spaniards, and a few Germans. The Eastern Christians included Greek Orthodox, Syrian Orthodox (Jacobites), Armenians, Georgians, Nestorians, and Copts.

Topography and Principal Buildings

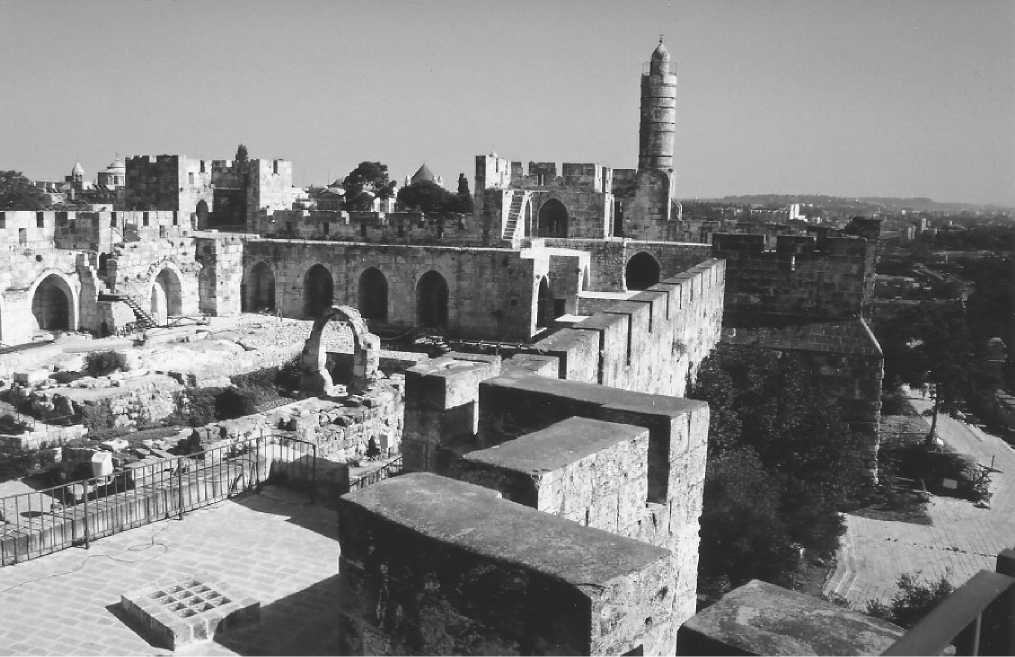

Jerusalem is situated in the Judaean highlands, about 58 kilometers (36 mi.) east of the coast and 30 kilometers (19 mi.) west of the river Jordan. The general layout of the medieval city roughly corresponds to the present-day Old City. The city was divided into four sections by its two main streets. The Romano-Byzantine Cardo ran from north to south, from St. Stephen’s Gate (mod. Damascus Gate) to the Zion Gate (east of the present gate), while the street running west to east, from David’s Gate (mod. Jaffa Gate) to the Beautiful Gate (mod. Gate of the Chain) corresponded to the Roman Decumanus. The city was protected by some 4 kilometers (21/2 mi.) of walls (mostly constructed in the eleventh century) and a citadel (known as the Tower of David) situated on the western wall by David’s Gate.

The greater part of the northwestern section formed the Patriarch’s Quarter, which constituted a separate lordship under the rule of the Latin patriarch, with its own administrative and judicial institutions. It included the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the patriarch’s palace, as well as a hospital, hospices, churches, monasteries, a grain market, a pig market, bath houses, bakeries, houses, and shops. There was a major water source, the so-called Pool of the Patriarch (mod. Hezekiah’s Pool). South of the Patriarch’s Quarter as far as David Street was the quarter of the Order of the Hos-

Aerial photograph of the Old City of modern Jerusalem (from the east), showing the layout of the medieval city. At the center of the western (top) section of the walls is the citadel (Tower of David) and nearby Jaffa Gate; to its right and below, the cupola of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The entire southeast section (bottom left) is taken up by the temple area (Haram al-Sharif) centered on the Dome of the Rock. (Courtesy Benjamin Z. Kedar)

Pital of St. John, which was bounded to the west by the Street of the Patriarch and to the east by the triple market. It included the Church of St. Mary Latin (Minor) with a monastery, the Church of St. Mary Major with a hospital, the Church of St. John the Baptist, and a market for poultry, fish, and cheese. The order maintained a hospice to provide accommodation for pilgrims as well as a large infirmary.

The northeastern section of the city had been the Jewish Quarter (Fr. Juiverie) until 1099; it became the Syrian Quarter when it was repopulated with Eastern Christians from Transjordan. Churches located here included St. Mary Magdalene situated near the northern wall, St. Agnes, St. Elias, and St. Bartholomew (all belonging to non-Latin denominations) and the Latin Church of St. Anne, built in 1140 as the chapel of a Benedictine nunnery.

Much of the southeastern section of the city was formed by the vast Temple Mount (Arab. al-Haram al-Sharif), where crusaders found two magnificent Muslim buildings: the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa mosque. The Dome of the Rock was converted into a church, which the Franks called Templum Domini (Temple of the Lord), which was consecrated on 9 April 1141. Al-Aqsa was known by the Franks as the Templum Salomonis (Temple, or more accurately, Palace of Solomon). It was used by King Baldwin I as the royal palace, although it had been plundered during the conquest and remained dilapidated; his financial difficulties prevented him from restoring it, and even forced him to strip the lead from the dome in order to sell it. It was granted by Baldwin II to serve as the headquarters of a newly founded order of knights, which became known as the Order of the

The citadel of Jerusalem, known as the Tower of David. The minaret was added when the walls were rebuilt by the Ottoman sultan Suleyman the Magnificent in the sixteenth century. (Courtesy Alfred Andrea)

Temple. The wealth of the Templars enabled them to undertake its restoration and to cover the surrounding area of the Temple Mount with new buildings. On the western side they built a new cloister, as well as courtyards, antechambers, vestibules, cisterns, storehouses, baths, and granaries, and laid the foundations of a great new church, which they never completed. The Templars also repaired the underground of al-Aqsa, called Solomon’s Stables, which were used to accommodate large numbers of horses and grooms. To improve access to them, the Templars opened a new postern on the southern Temple Mount wall, known as the Single Gate (now blocked).

To the west of the Temple Mount, the southeastern quarter was bordered by the southern wall and the streets built along the line of the Cardo to the west. In the center of the quarter were located money exchanges, the Latin exchange to the south and the Syrian exchange farther north. To the south were the German hospice and church, and farther south, the cattle market and tanneries. A covered market and parallel streets bordered the quarter to its west.

The southwestern quarter of the city was occupied (as it is today) by the Armenians, bounded by the city wall south of David’s Gate and by the southern wall up to Zion Gate. Churches in this quarter included St. James, St. Thomas, St. Mark, and St. Sabas.

Outside the city’s walls the most important buildings were the Cenacle (Lat. Coenaculum), or chapel of the Last Supper, on Mount Zion, the Church of the Ascension on the Mount of Olives, the Church of St. Mary in the Valley of Jehosaphat, and St. Stephen’s Church to the north of St. Stephen’s Gate. To the west of the latter church were a leper house and other buildings belonging to the Order of St. Lazarus.

The crusader period saw a major rebuilding in the city. The walls and citadel were renovated, and several of the city’s gates were either renovated or embellished, while some forty churches were either rebuilt or newly constructed, all in the Romanesque style. One of the most ambitious of the construction projects undertaken by the Franks was the rebuilding of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in order to unite all the buildings on the site of Christ’s Crucifixion, burial, and resurrection under one roof. The new church was consecrated on 15 July 1149, the fiftieth anniversary of the capture of the city. Another fine example of Frankish Romanesque construction was the Church of St. Anne, erected near the Pool of Bethesda at the traditional site of the house of the parents of the Virgin Mary, Anne and Joachim. It housed a few Benedictine nuns until Baldwin I repudiated his second wife and placed her in this convent, increasing its patrimony and possessions. The nunnery of St. Anne remained in royal favor, and it was there that Yvette, sister of Queen Melisende, made her profession in 1130. Another important church rebuilt by the Franks on the ruins of a Byzantine one was the Church of the Ascension on the Mount of Olives.

Administrative Status and Institutions

Up to 1187, the city was the administrative center of the kingdom, being the normal place of residence of the king and the meeting place of the High Court (Fr. Haute Cour), which met first in the Temple of Solomon and from the 1120s in the new royal palace next to the citadel. Apart from the Patriarch’s Quarter, the city and its surrounding territory formed part of the royal demesne. The main court of the city proper was the Court of Burgesses (Fr. Cour des Bourgeois), which dealt with civil cases concerning the Frankish burgesses and their property and also had supreme criminal jurisdiction over all non-noble inhabitants of the city, including Eastern Christians. The Court of the Market (Fr. Cour de la Fonde) had jurisdiction over the entire non-Frankish population in all except criminal cases. Both courts met in the Tower of David. Preservation of the peace was the responsibility of a viscount, who acted as governor of the city, presided over the Court of Burgesses, organized police duties, oversaw the city’s markets, and collected royal revenues deriving from the city. The defense of the city and its citadel was the responsibility of a castellan, who acted as commander of the garrison.

Economic Life

Jerusalem was not involved in long-distance trade, and unlike the kingdom’s ports, it had no Italian commercial quarters. The city’s main economic activity was providing services for its secular and ecclesiastical institutions and their personnel and for the pilgrim traffic from the West. In the very heart of the city, north of the intersection of the two main axes, were located the main bazaars of Jerusalem, consisting of a triple market of three parallel vaulted streets. The central street was known as the Street of Evil Cooking (Fr. Malcuisinat) from its principal activity, the sale of ready-cooked meals to pilgrims visiting the city. The shops and bazaars belonged to Frankish and Eastern Christian merchants, as well as to various convents and the military orders: inscriptions reading (sca) anna or T can still be seen on some of the shop walls, indicating ownership by the convent of St. Anne or the Templars. There was a cotton market on the western side of the Temple Mount esplanade, a chicken market at the southern side of the Hospitaller complex, and a butchers’ market opposite the street leading to St. Mary of the Germans. There were also open streets lined with shops (for example, on the northern side of David’s Street) and open markets in the fields outside the city walls, including a large grain market north of David’s Gate and a cattle market to the south of the city. Jerusalem also had a mint, whose precise location is uncertain.

Religious and Secular Festivals

The liturgical life of the city was focused on the two main churches, which were also the main objects of pilgrimage: the Church of the Holy Sepulchre as the symbol of New Testament Jerusalem and the Temple of the Lord representing the Jewish Temple, the center of Old Testament Jerusalem. Besides the great feast days common to all Christendom, were some unique to the city. The miracle of the Holy Fire, attested from the mid-ninth century under the Greek Orthodox Church, continued to be celebrated on the eve of Easter Day in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the presence of the massed clergy and people, who waited anxiously until a light appeared miraculously in one of the lamps that hung above the tomb of Christ, to be greeted with great rejoicing.

A new feast introduced by the Franks was held on 15 July to commemorate the capture of the city in 1099 and the consecration of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre fifty years later. It began with a procession led by the patriarch from the Holy Sepulchre to the Temple of the Lord, and from there across the Temple Mount esplanade to the burial place of those who died during the siege of1099; this place was located just outside the city, not far from the spot in the northeastern angle of the walls, marked by a cross, where the knights of Godfrey of Bouillon first penetrated the city. Here the patriarch preached a sermon to the assembled clergy and populace and offered thanksgiving prayers commemorating the event.

Of the nine rulers of the first kingdom (1099-1187), seven were crowned in Jerusalem. The future king, members of his family, and officials rode from the royal palace to the Holy Sepulchre, where he was crowned by the patriarch. The procession then made its way to the Temple of the Lord, where the new monarch placed his crown on the altar, symbolically commemorating the presentation of Jesus in the Temple (Luke 2:25-35). The last full coronation ceremony, that of Queen Sibyl and Guy of Lusignan, took place on 20 July 1186.

Jerusalem after 1187

Following the defeat of Guy of Lusignan’s army by Saladin at the battle of Hattin (4 July 1187), Jerusalem surrendered after a fortnight’s siege (2 October 1187). Most of the Frankish inhabitants were able to buy safe passage to the coast, but many were enslaved. Following Saladin’s entry, the cross over the Temple of the Lord was taken down and all signs of Christian worship removed, while al-Aqsa was cleaned of all traces of its occupation by the Templars. Both buildings were dedicated once more to the service of Islam, and on Friday, 9 October 1187, Saladin was present with a vast congregation to give thanks to his God in al-Aqsa.

Jerusalem reverted to Frankish rule during the period 1229-1244, when as a result of the Treaty of Jaffa (18 February 1229) between Emperor Frederick II and Sultan al-Kamil of Egypt, the kingdom regained Jerusalem and Bethlehem with a corridor of territory to the coast at Jaffa (mod. Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel), although the Temple Mount remained in Muslim hands and Muslims were allowed the right of entry and freedom of worship. On Saturday, 17 March 1229, Frederick entered Jerusalem with his troops, members of the Teutonic Order, and some of the local baronage; the next day he had a royal crown laid on the altar of Calvary and placed it on his own head, despite an interdict laid against the city by Patriarch Gerold if it should receive the excommunicated emperor.

During the period 1229-1244, some repairs were carried out to the city’s walls, which had been destroyed by the Ayyubids in 1219, while certain institutions such as the military orders sent representatives to claim back their possessions in the city. There is also evidence of reorganization of municipal administration through the reestablishment of the offices of castellan and viscount, but the city lacked an adequate garrison. When al-Nasir, the Ayyubid ruler of Kerak, assaulted the city in 1239 in retribution for an attack by the forces of the crusader Thibaud IV of Champagne on a Muslim caravan, he was able to occupy it without difficulty. The soldiers in the citadel held out for twenty-seven days until their supplies were exhausted, surrendering on 7 December in return for a safe-conduct to the coast. Al-Nasir withdrew after destroying the citadel and other fortifications, and the city remained unfortified until the walls were rebuilt by the Ottomans in the sixteenth century.

The Temple Mount was restored to the Franks in 1244 as a result of a treaty between the Franks and a coalition of the rulers of Homs, Kerak, and Damascus against the Ayyubids of Egypt. However, a few months later the Egyptian sultan al-Salih Ayyub called in nomadic Khwarazmian mercenaries; as they approached the defenseless city, the remaining inhabitants left in an effort to march to safety (23 August 1244), but almost all were massacred by the Khwarazmians, only a few hundred reaching Jaffa. Most of the churches of Jerusalem were burned, and the houses and shops pillaged; the bones of the kings of Jerusalem in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre were torn out of their tombs before the building itself was consigned to the flames.

The Khwarazmian conquest ended Frankish rule in Jerusalem. The recovery of the Holy City continued to figure in crusading plans of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, but this goal receded with the advance of the Ottoman Turks into Europe. Jerusalem continued to attract Christian pilgrims, but it had no permanent Latin Christian inhabitants until the Franciscans were permitted to settle at Mount Zion in the mid-fourteenth century.

-Sylvia Schein

Bibliography

Boas, Adrian J., Crusader Archaeology: The Material Culture of the Latin East (London: Routledge, 1999).

-, Jerusalem in the Time of the Crusades: Society,

Landscape and Art in the Holy City under Frankish Rule (London: Routledge, 2001).

Boase, Thomas S. R., “Ecclesiastical Art in the Crusader States in Palestine and Syria,” in A History of the Crusades, ed. Kenneth M. Setton et al., 6 vols., 2d ed. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969-1989), vol. 4, 69-139.

Folda, Jaroslav, The Art of the Crusaders in the Holy Land, 1098-1187 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Hamilton, Bernard, “Rebuilding Zion: The Holy Places of Jerusalem in the Twelfth Century,” Studies in Church History 14 (1977), 105-116.

-, “The Impact of Crusader Jerusalem on Western

Christendom,” Catholic Historical Review 80 (1994), 695-713.

A History of the Crusades, vol. 4: The Art and Architecture of the Crusader States, ed. Harry W. Hazard (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1977).

Jerusalem im Hoch - und Spdtmittelalter: Konflikte und Konfliktbewdltigung—Vorstellungen und Vergegenwdrtigungen, ed. Dieter Bauer, Klaus Herbers, and Nikolas Jaspert (Frankfurt am Main: Campus, 2001).

Kedar, Benjamin Z., “The Jerusalem Massacre of July 1099 in the Western Historiography of the Crusades,” Crusades 3 (2004), 15-76.

Prawer, Joshua, The Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem: European Colonialism in the Middle Ages (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1972).

-, “Crusader City,” in The Medieval City, ed. Harry A.

Miskimin, David Herlihy, and A. L. Udovitch (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977), pp. 179-199.

-, Crusader Institutions (Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 1980).

-, “The Jerusalem the Crusaders Captured: A

Contribution to the Medieval Topography of the City,” in Crusade and Settlement, ed. Peter W. Edbury (Cardiff: University College Cardiff Press, 1985), pp. 1-16.

Schein, Sylvia, Gateway to the Heavenly City: Crusader Jerusalem and the Catholic West (1099-1197) (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2005).

Wilkinson, John, with Joyce Hill and W. F. Ryan, Jerusalem Pilgrimage, 1099-1185 (London: Hakluyt Society, 1988).

World History

World History