The traditional view of the later tenth century and the reign of Basil II is that of a Golden Age, in which the empire attained the height of its power. In terms of international esteem and territorial extent this is not incorrect, but the result is that the reigns of Basil II’s successors are inevitably compared unfavourably with what went before. Basil left no children and was succeeded by his brother Constantine VIII, who ruled just three years alone before he too died. Constantine’s elder daughter Zoe now determined who should become emperor according to whom she married. In the period from 1028 until 1042 she had in succession three husbands who became emperor through her: Romanos III Argyros (1028-1034), Michael IV ‘the Paphlagonian’ (1034-1041) and Constantine IX Monomachos (1042-1055). The predominantly civilian power elite at Constantinople took the stability achieved by the end of Basil II’s reign for granted, and proceeded to a radical reduction of the standing army and frontier militias - in order to limit the power and ambition of the provincial ‘military’ elite. In doing so, however, they did not, and perhaps could not, take into account changing circumstances outside the empire. The military elite were just as concerned with their own position within the empire and their relations with the governing clique and the emperors. Provincial rebellions in Bulgaria in the 1030s and 1040s, a result of misguided fiscal policies as well as political oppression, foreshadowed greater problems. The arrival on the Balkan frontiers of the Pechenegs, a Turkic steppe people, at about the same time, and their first incursions into imperial territory, similarly should have alerted the emperors and their advisers. The rebellion in 1042-1043 led by George Maniakes, commander of the imperial forces in Sicily, was cut short by the death of its leader, but nevertheless indicated that there was considerable unrest and discontent among leading elements of the elite. The brief reign of the Emperor Isaac I Komnenos (1057-1059), a soldier of the Anatolian military clans, indicated the direction of change. And although the empire continued to expand its frontiers in the Caucasus, efforts to re-establish imperial control in Sicily and southern Italy failed, so that by the early 1070s the empire had lost its last foothold there to the dynamic Normans.

As well as the Pechenegs in the north, a new and yet more dangerous foe appeared in the 1050s and 1060s in the east, in the form of the Turkic Seljuks, a branch of the Oguz Turks (called Ouzoi by the Byzantines) who had already established themselves as masters in the Caliphate, and whose energies were now directed northwards from Iraq into the Caucasus and eastern Asia Minor. The Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes (1068-1071) made an attempt to stem the flow of raids and incursions, but after some initial success, a combination of treachery and tactical blunders led to his defeat in 1071 at the battle of Manzikert in eastern Anatolia. Losses following the battle were in themselves not great, and the evidence suggests that the strategic situation could have been rescued. But Romanos himself was captured, and although ransomed after a brief period as the guest of the Sultan Alp Arslan, found that he had been deposed. Civil war broke out and the empire’s remaining forces exhausted and weakened themselves in the conflict that followed. Asia Minor was simply left open, and Turkic herdsmen with their flocks, families and chattels moved in to the central plateau, ideally suited to their way of life (in contrast to that of the Arabs who, in the seventh century, had signally failed to make this transition). Further civil conflict ensued, and by the time the general Alexios I (1081-1118) seized the throne in 1081, the empire had lost central Asia Minor, while the Balkans were overrun by Pecheneg raiders and the Normans had invaded the empire from their base in southern Italy.

Alexios had restored stability by 1105 through good planning, diplomacy and able generalship. The Pechenegs were defeated and settled within the empire as soldiers in the imperial army; the Normans were thrown out of Epiros; the Seljuks were checked. Alexios astutely used the armies of the First Crusade to help as they passed through Byzantine territory in 1097-1098. He carried out administrative reforms and he allied himself through marriage and the imperial system of offices with other elite clans in order to re-establish an effective central administration. Under Alexios’ son John II (1118-1143) substantial tracts in western Asia Minor were recovered, while under Manuel I (1143-1180) the imperial position in the Balkans was strengthened and imperial armies began slowly to push into central Anatolia again. But tactical misjudgement led to the defeat at the battle of Myriokephalon near Ikonion in 1176, ending Byzantine efforts to recover the central plateau. The empire was never again in a position to mount such a campaign in the region, and the ‘Turkification’ - and Islamisation - of central Asia Minor were firmly under way.

Along the Danube the Hungarians were coped with, but the empire was becoming an increasingly European state. At the same time a number of relatively new political powers entered the historical stage.

First, the maritime power of Venice (followed by Genoa, Pisa and Amalfi) introduced a new element into the economic as well as the political relations between Byzantium and the west, and the imperial government made several concessions in respect of customs and trading privileges to these city-states. Secondly, the empire had to deal with a complex situation in its relations with the German emperors and with the nascent power of the Sicilian Norman kingdom. The Crusades transformed the political situation: while the Crusaders themselves established a series of fragile principalities around the Kingdom of Jerusalem, they also brought with them the vested interests of the western powers, whose interest in what had been an exclusively Byzantine sphere of influence grew. John II and Manuel were able to maintain good relations with the German emperors, playing them off, for example, against the Normans of Sicily.

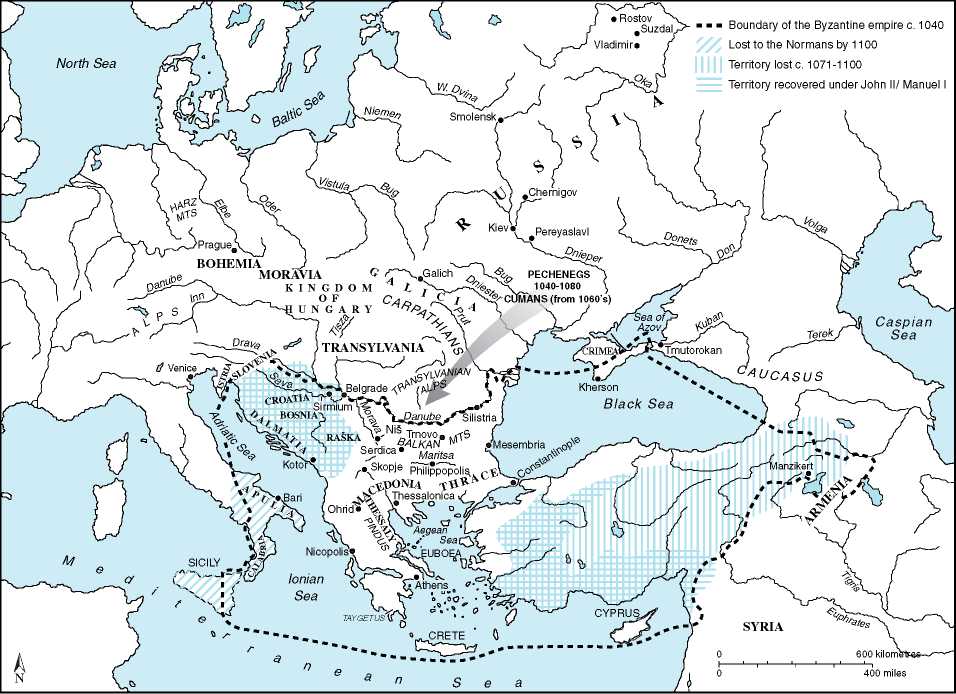

Map 9.1 The empire in context 1050-1204.

Yet on the death of the Emperor Manuel I, the system he had built up quickly fell apart, and the fragility of the imperial position soon became apparent.

Manuel left no heir competent enough to deal with this inheritance, and the empire was riven by petty dynastic squabbles. The hostility of the Italian cities and other western powers was provoked by attacks on westerners - in 1182, for example, a massacre of western merchants was orchestrated by Andronikos I. In 1185 the Normans exploited the situation by attacking and sacking Thessalonica, the second city of the empire. Andronikos was deposed and killed in 1185 and succeeded by Isaac II Angelos (1185-1195), a relation of the Komnenos clan; he was replaced by his brother Alexios III Angelos in the years 1195-1203. In this latter year, however, the armies of the Fourth Crusade appeared before Constantinople. Alexios III was removed, to be succeeded by Alexios IV.

A rebellion in Bulgaria in 1185 led to the defeat of imperial garrisons and the re-establishment of an independent Bulgarian state. Isaac II was himself heavily defeated in 1190 in an effort to check the revolt; while Serbia, which had occupied the position of a vassal state for some time, began also to distance itself from the empire, partly a result of the empire’s wars with Hungary. Isaac was able to stabilise the situation through a successful military campaign and a marriage alliance. But it was apparent that imperial power and authority were in decline on every front; by 1196 Serbia had turned to Rome rather than Constantinople for political support, while the situation in Bulgaria was hopeless; and in 1189 Cyprus was also lost to the English under Richard I in the course of his crusading campaign.

The Crusades 1096-1204

Military expeditions organised or inspired by the papacy and aimed at the protection of pilgrims and Christian holy places or to help fellow Christians in their struggle against unbelievers had begun already in the 1060s when knights from Burgundy and Languedoc marched to fight with the armies of Castile in Spain. The reform movement in the western church, which affected the papacy and its policies, coincided with a renewed threat, in western eyes, to the Holy Land from the Seljuks, whose capture of Jerusalem and Syria from the Fatimids directly affected western pilgrims. Unarmed pilgrimages were a well-established tradition, and Seljuk interference caused considerable anger. At the same time, the notion of holy war against the heathen was growing in popularity and in 1095 at the Council of Clermont the Pope, Urban II, responding to a request from the Emperor Alexios I for military aid, preached that knights should join a crusade to recover Jerusalem. In 1096 an unorganised crusade of adventurers led by a certain Peter the Hermit arrived at Constantinople and was transferred to the Anatolian side, where it rapidly disintegrated under Seljuk attacks. Between 1096 and 1099, however, a much more effective expedition was conducted under the leadership of several leading nobles. The northern French contingent was led by Duke Robert of Normandy, those of Lorraine and the Flemish lands by Godfrey of Bouillon, Baldwin of Boulogne and Robert II of Flanders, and those of southern France by Raymond of Toulouse. The Normans of southern Italy were led by Bohemond of Tarento and his nephew Tancred. The forces of Godfrey marched across Germany and down through Hungary to enter Byzantine territory (some of the Crusaders also attacked several Jewish communities en route), while those of Raymond of Toulouse marched along the Adriatic shore lands of Croatia to enter Byzantine territory north of Dyrrhachion (mod. Durres). The Normans crossed the Adriatic and entered the empire further south on the coast of Epiros. The Emperor Alexios was able to provide supplies for them and, on the whole, to keep the peace between his own soldiers and the subjects of the empire and these substantial alien armies, eventually - after extracting oaths of fealty from the leaders - helping them to cross the Bosphorus and engage the Seljuks. Although initially outwitted by Seljuk tactics, the Crusader leaders quickly adapted to the new conditions. Defeating the Seljuk Sultan at Dorylaion, Antioch was taken after a seven-month siege, and eventually Jerusalem itself was captured in July 1099.

The result was the foundation of a number of Crusader states. The most important was the Kingdom of Jerusalem (whose first king, with the title ‘protector of the Holy Sepulchre’, was Godfrey of Bouillon), followed by the Principality of Antioch (claimed, however, by the Byzantines), taken by Bohemund, and the Counties of Edessa and Tripolis. Weakened by internal fighting and conflict as well as by conflict with Byzantium, the city of Edessa, which had become an important Crusader stronghold, was taken by the Zengid emir of Mosul in 1144. This led directly to the preaching of the Second Crusade (11471149), led by the German Emperor Conrad III and the French King Louis VII. But the effort was weakened by the conflicting foreign policy interests of the two (the German emperor allied with Byzantium against the interests of the Norman King of Sicily, and the latter allied with the French). The result was defeat at the hands of the Seljuks and unsuccessful expeditions against the Muslim strongholds of Ascalon and Damascus. Continued Crusader rivalries and factionalism as well as an essentially untenable strategic position led to the capture of Jerusalem in 1187 by the general Saladin, founder of the Ayyubid dynasty, who took over the empire built up by the Zengid emir Nur ad-Din.

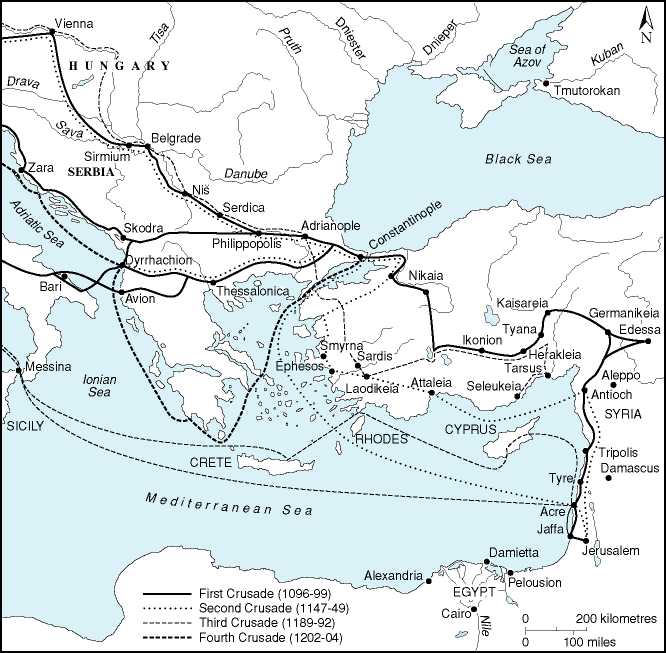

Map 9.2 The Crusades 1096-1204.

The Third Crusade which followed (1189-1192) was led by the German Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa, and consisted of three separate columns, his own, across the Balkans and via Constantinople; that of Richard I of England, which sailed via southern France, the toe of Italy and Cyprus (which was seized from the Byzantines en route); and that of Philip II Augustus of France which sailed from Genoa via southern Italy to the Holy Land. After a victory over the Seljuks at Ikonion Frederick drowned while crossing the river Kalykadnos (Salef) and his son, Duke Frederick of Swabia, took over. His army reached Acre, but Frederick died in 1191; Richard and Philip succeeded in taking Acre, and a treaty was eventually concluded with Saladin, whereby Tyre and Jaffa were ceded to the Crusaders, and pilgrimages to Jerusalem were to be permitted without hindrance. Cyprus was given as a fief to Guy of Lusignan.

The Crusades represented what was to be, in the last analysis, a strategically impossible task. Apart from the financial and resource problems posed by the need to defend such a long and exposed frontier, the Crusader states were perpetually short of manpower, had problems with maintaining their stock of warhorses, and were split by internal rivalries. But they were given a certain strength and resilience by the efforts of the military religious orders of knights, the Knights of St John and the Knights Templar. The latter, formed in 1120 with their mission the protection of pilgrims and securing the conquest of the Holy Land, formed a core of highly trained and effective soldiers. The former, originating in a fraternity attached to the hospital of St John in Jerusalem, became a military order in 1120 also and, like the Templars, acted as a key support of the Crusader states until forced to leave the Holy Land in the late thirteenth century.

World History

World History