Any number of bacteria can produce inflammation due to infection, which normally starts in the soft tissues of the body and, only upon becoming chronic, produce bony reactions. These generalized reactions that lack the appearance and patterning of specific bone disease, as well as those that cannot be determined due to inadequate preservation of the skeleton, are termed ‘nonspecific’ disease. The most commonly occurring type of bone reaction is due to the infiltration of skin bacteria, most commonly by Staphylococcus aureus, into an open wound that causes inflammation and new bone formation (Figure 2). If the bacteria gain entry to the medullary canal, osteomyelitis results with its distinctive sheath of bone formation called an involucrum, its pus-draining sinuses called cloacae (singular cloaca), and a sequestrum, necrotic or dead bone (Figure 3). Due to the skin’s role as a protective barrier, these bacteria do not normally pose a health threat. In individuals who suffer from a compromised immune system, through disease or injury, these bacteria enter the bloodstream and can cause infection some distance from the point of entry. Due to their nondiagnostic pattern, the prevalence of these nonspecific bone reactions is used to indicate that individuals and populations had experienced ‘stress’ that led to infection.

Stress may result from a variety of causes, physical as well as mental, that act to reduce the immune response such that an individual is at a heightened risk of ill health. Because these conditions have multiple etiologies, they are often used as a population-level indicator of stress. Stress also influences the development of skeletal structures: lines of arrested growth or Harris’ lines in long bones, enamel hypoplastic defects in teeth

Figure 2 This section of tibia shows striated woven or fiber bone from a Medieval Blackfriars house, Gloucester. Photograph courtesy of Prof. Donald J. Ortner, Smithsonian Institution, from the collections of the Biological Research Centre (BARC), University of Bradford.

(Figure 4), subperiosteal infection (new bone formation on the cortical surface of bones indicative of inflammation of the periosteum) (Figure 2), porotic hyperostosis and cribra orbitalia (indicators associated with iron deficiency) (Figure 5), and thinning of cortical bone in long bones (an indicator of malnutrition). These are usually recorded in a presence or absence manner and prevalence rates for a given population calculated on the number of bones observed and affected (to indicate the state of skeletal preservation of the skeletal material).

Teeth, being the most highly mineralized body structures, are a unique and, indeed, are sometimes the only source of information relating to past individuals and the societies to which they belonged. Their health is a good indicator of individual and population health. Unlike bone, in life, teeth interact directly with the environment (chewing, wear, and trauma) and, after death, are highly resistant to most taphonomic processes. The well-preserved lesions produced by diseases of teeth and jaws can also tell us much about diet, which is strongly related to culture and economic and social status. Unlike bone, teeth do not undergo remodeling or repair in life, so they retain deposits laid

Figure 4 Teeth from an 8-year-old from Medieval Hereford, showing depressed bands of poorly formed (hypoplastic) enamel, revealing that this individual had been very unwell or severely malnourished at 3-4 years of age when these regions of the teeth were developing. Photograph courtesy of Alan R. Ogden from the collections of the Biological Anthropology Research Centre (BARC), University of Bradford.

Figure 3 Osteomyelitis, chronic bone infection, secondary to a fracture of the femur in a male from Medieval Chichester, West Sussex, UK. The bony sheath of reactive new bone, the involu-crum, can be seen to envelop the distal end of the bone. A large, pus-draining sinus, a cloaca, can be seen in the popliteal space. A sequestrum can be seen in the cloaca, which, in this case, has been retained through a re-established blood supply and subsequent fusion to the margin of the cloaca. Photograph courtesy of Prof. Donald J. Ortner, Smithsonian Institution, from the collections of the Biological Research Centre (BARC), University of Bradford.

Figure 5 The resorptive changes of diploic hyperplasia of cribra orbitalia in the orbits of an individual from Late Anglo-Saxon, Thetford, Norfolk, UK. Note that these are resorptive (i. e., loss of bone) lesions, unlike those in Figure 22. Photograph courtesy of the Calvin Wells Collection, Biological Anthropology Research Centre (BARC), University of Bradford.

Figure 6 Lower left mandible of an adult from Medieval Hereford, showing the decayed, dead, and worn roots of a molar that developed a chronic abscess. Note, too, the flat wear of the remaining molar and the tipped and impacted wisdom tooth behind it.

Down in layers during childhood and adolescence. Teeth, then, retain permanent indications of diseases linked to diet, such as caries, abscesses, and tooth loss (Figure 6), as well as to stressful episodes, especially in the young when teeth are developing.

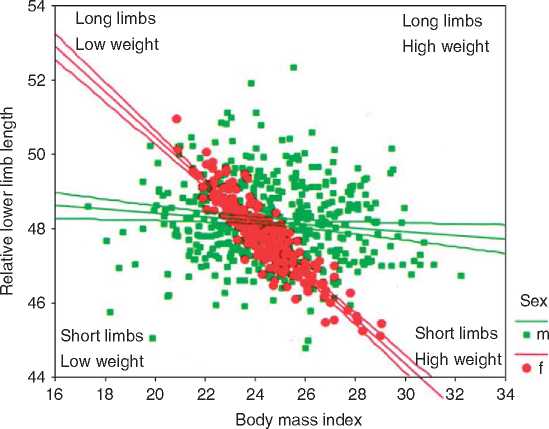

A group of relative indicators complements these indicators of health, including growth studies of subadults based on dental development and limb length, adult attained stature, sexual dimorphism (less sexuaLly dimorphic populations tend to be less healthy), and asymmetries of bilateral structures due to development instability (i. e., fluctuating asymmetry) in the dentition and skeleton of adults and subadults. In general, males appear to be more sensitive to growth-disrupting stress than females (Figure 7). Life

Figure 7 The relationship between body mass and relative lower limb length among 1351 males (green) and females (red) of populations dating from the Roman to Medieval periods. Individuals of a lower social status would tend toward the lower-left quadrant (short limbed and light weight, indicating growth stunting), and those of a higher social status would tend toward the upper-right quadrant of the graph (long limbs and heavier, indicating better growth circumstances). Note the diffuse scatter of males, who are more susceptible to environmental insult, compared to the females, who are much less scattered. Schweich M (2005) Diachronic Effects of Bio-Cuiturai Factors on Stature and Body Proportions in British Archaeological Populations. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Bradford.

Expectancy from birth also features as a relative source of information on population health, but such studies are hampered by difficulties in precisely aging adults after the attainment of physiological maturity.

World History

World History