The Olmec represent the culmination of milleniums of lowland Mesoamerican cultural development that resulted in a burst of sociopolitical change during the course of the second millennium BC, reaching an apogee during the Early Horizon period that saw San Lorenzo’s dominance and participation in the foundations for later Mesoamerican political and economic systems during the Middle and into the Late Formative periods. During the roughly 1600 years represented by these developments, the societies of the southern Gulf lowland region of Veracruz and the adjacent Tabasco Coastal Plain underwent fundamental economic and cultural transformations that saw the rise of a mixed agrarian economy in the rich, seasonally flooded lowlands of the region, followed later by shifts toward the classic Mesoamerican maize-based subsistence economy, the emergence of complex social and political-economic networks reflected in archaeological settlement hierarchies, the differentiation of society into a ranked and occupationally differentiated population, the emergence of kingship, political rituality, and the development of the foundations of writing. A diverse subsistence base, consisting of wild plant and tree use, a range of domesticated species, wild mammal, reptile, and fish species, as well as coastal shellfish, constituted a rich, cyclic resource base that provided a calorie and protein base that allowed for the florescence of complex culture in the region. Within the exceptionally rich region of the riverine and deltaic lowlands (Figure 2), this resource base fueled the emergence of complex networks of communities ranging from small hamlets located along natural levees, larger villages and village clusters, some with evidence of community structures, to towns and polity capitals such as San Lorenzo, La Venta, and Tres Zapotes. Though the complexity of the San Lorenzo region appears unmatched during the Early Horizon, later developments in the Olmec region are part of the developing mosaic of Mesoamerica and demonstrate multifaceted linkages with other regions. Stylistic links, commodity and gift exchanges, and outright expansions out from the Olmec Gulf Coast lowlands suggest a complex picture of interrelationships and rivalries.

Chronology of the Olmec Heartland

In general terms, the chronology of the Olmec can be divided into the Initial Formative, Early Formative, Middle Formative, corresponding to the Olmec proper, and the Late Formative, characterized by a series of Epi-Olmec societies that continued to experiment and innovate. Archaeological evidence for very early populations is largely absent, either buried under meters of alluvium, laterally eroded by meandering channels, or lying unremarked and potentially deflated

Figure 2 Modern canoe in a palaeodistributary of the Grijalva River delta. Photograph by Christopher von Nagy.

In upland areas where erosion may have dominated long-term landscape processes. The earliest evidence for a ceramic-using population corresponds with the Ojochi or Pellicer ceramic complexes of the Coatzacoalos river basin, El Manati, and the western Grijalva delta in Tabasco (see Table 1 And Figure 3). This pottery tradition demonstrates significant stylistic links to southern Chiapas paralleling the linguistic suggestion of a northern immigrant group of Sokean speakers. Cultural patterns, such as ritual beverage consumption, are an important aspect of the pottery tradition from this early period through to the beginning of the post-La Venta Epi-Olmec period.

The apogee of San Lorenzo and the Coatzacoalcos River region coincides with the last part of the Early Formative period and, due to the widespread appearance of Olmec iconography on pottery and other artifacts, is sometimes termed the Early Horizon. Early

Formative populations are present but poorly understood in the area of Tres Zapotes and are present in low density in the Tuxtlas. Like the Coatzacoalcos floodplain, the western Grijalva delta has a substantial Early Formative occupation to the east of La Venta.

The Middle Formative period marks a population expansion into new areas, such as Laguna de los Cerros, the fringe of the Grijalva delta where La Venta is located, but a general collapse in the Coatzacoalcos lowlands. Dense populations are documented along a number of distributary channels in the Grijalva delta. The Middle Formative Olmec region is marked by several ceramic horizons, which like the Early Horizon complexes, document connections ranging from coastal Chiapas to the south, the Usu-macinta region to the east, and Central Mexico to the west. In the east, an increasingly evident Maya presence is noted at the end of the Olmec period. This

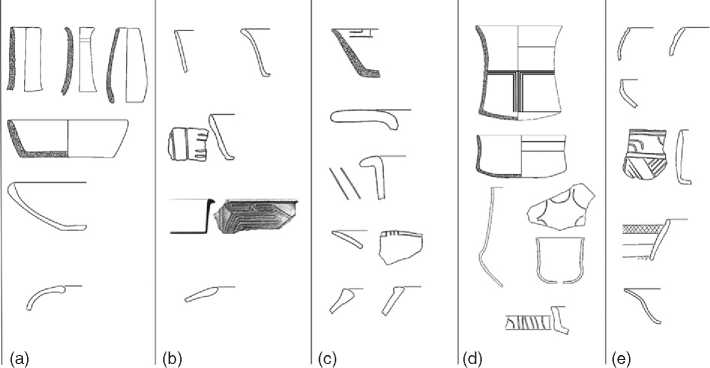

Early Ojochi complex pottery around San Lorenzo and Pellicer complex pottery in Tabasco mark the beginning of the documented ceramic traditions of the Olmec region. Bottles, simple to slightly complex bowls, simple dishes, plain and red slipped vessels dominate collections at this point. Tecomates are very common. Reduplication of botanical forms - squash and gourds - is an important aspect of this tradition. Rimmed vessels similar to Ocos examples from southern Chiapas are common. Increasingly common use of differential firing of, in particular, bottles for ritual beverage consumption.

Early Horizon complexes Figure 3 column B

Early Horizon phase pottery from the Olmec area manifests a series of changes linked to the formation of an extensive horizon marked by distinctive gouge-incised and ‘Olmec’ iconography and curvilinear, often pars pro toto references to elements of the broader emergent Early Formative signary. Drop in the frequencies of bottles indicating important changes in the social use of fancy pottery. Dishes with flared sides, outcurved dishes, plain and striated tecomates, and rim bolstering manufactured of white-clear through, black clear through, white-slipped, and differentially-fired pottery are typical elements of assemblages. Some areas of interior Chiapas, such as the Grijalva corridor at the now flooded site of San Isidro demonstrate strong similarities to coastal pottery traditions.

Middle Horizon complexes Figure 3 columns C, D, and E

Ceramically, the Middle Formative can be divided into successive complexes. Initial Middle Formative complexes are characterized by flared bowls and dishes, some with massively everted rims, and commonly decorated with variations on the ‘double-line break’ motif, plain smaller tecomates, and larger cooking tecomates, later ollas, are common forms (column C). Perhaps as early as 700 BC a ceramic shift occurs with the appearance of composite silhouette dishes with flared walls and a variety of other novel forms (column D). A wide range of forms was produced, including flared wall serving dishes and plates linked to public feasting and rituality. Sometime around 500 BC shifts in bowl and plate design occur with the introduction of saddle-rimmed bowls (column E), wide-rimmed, flared-wall dishes, and changes in surface decoration. Repeated, close stylistic similarities to coastal Chiapan pottery.

Epi-Olmec complexes

The failure of La Venta around 400 BC marks the end of the thousand year period generally understood as ‘Olmec.’ Sites such as Tres Zapotes continued as major focal points of population. Innovations in the Late Formative or Epi-Olmec period such as the development of a fully developed writing system occurred during this period. At Tres Zapotes and other sites around the Tuxtlas there is an essential continuity in the types and forms produced. In Tabasco, the collapse of La Venta coincides with the spread of Maya ceramics into western Tabasco.

Figure 3 Ceramics of the Olmec region. (a) Pre-Early Horizon bottles and contemporary forms. (b) Early Horizon gouge-incised and selected contemporary forms. (c) Selected Early Middle Formative forms associated with Early La Ventaand neighboring sites. (d) Middle Formative forms associated with the apogee of La Venta. (e) Middle Formative forms associated with the terminal Formative occupation at La Venta with design similarities to Tuxtla and Tres Zapotes forms. Redrawn from von Nagy 2003 and (vessel B3) Coe MD and Diehl RA (1980) In: The Land of the Olmec. The People of the River. Austin, TX: The University of Texas Press.

Phenomenon is also evidenced in the Isthmus focus of Epi-Olmec societies such as Tres Zapotes and the society that produced the La Mojarra stela, lasting until the arrival of increasingly strong Central Mexican influence ultimately tied to Teotihuacan.

Calendar dates for Olmec ceramic phases and complexes are based on an increasingly large and reasonably well-contextualized set of radiocarbon assays, including samples from well-delineated middens in bell-shaped or larger pits or on palaeobotanical remains using accelerator dating. Nonetheless, many dates still derive from charcoal recovered in fill and less ideal contexts. Early Olmec dates calibrate well, but Middle Formative date calibration presents a particular and yet unresolved challenge due to changes in the production of upper atmosphere 14C. Dates in the range of roughly 800-400 BC (c. 1005-400 cal BC) are exceptionally difficult to use. Calibrated probability ranges allow for errors of a hundred years or more. A date in the uncalibrated range of 750-400 BC has a high probability of falling within any portion of this range. Due to this problem, phase and complex boundaries should remain tentative.

Olmec Subsistence Strategies and Food Ritual

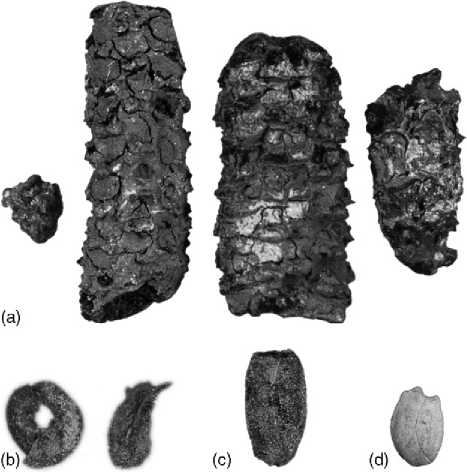

Olmec foodways comprised a varied diet. Patterns of consumption of maize, sunflower, and manioc as well as wild foods such as squash and nuts of the corozo plam established in the Archaic period by c. 5000 BC underwent elaboration during the Early and Middle Formative periods after 1500 BC. Domesticated beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) were added to the menu. Domesticated dog (Canis familiaris) was the single most important source of meat (10% of the vertebrate remains) at San Lorenzo in the Early Formative period. Early Formative Olmec also focused on aquatic resources, particularly snook (Centropomus or robalo), an estuarine fish that would have been available near San Lorenzo during the rainy season floods, and mud turtles (the closely related species Claudius, Kinosternon, and Staurotypus). Larger terrestrial mammals such as deer were scarce.

A shift in the Middle Formative period set the course for dietary preferences characteristic of later Mesoamerican cultures (Figure 4). Data available for the La Venta client site of San Andriis show a new focus on white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), especially in deposits that represent remains of feasting. This shift might have had ritual symbolic significance in terms of an Olmec predator/prey or victor/ vanquished ideology with deer representing the prey. Later elites, such as the Maya, would copy this hallmark of the Olmec diet.

Maize was a significant element of the diet as well as the iconography and early glyphs though its position was more restrained than seen in later Mesoamerican cultures. San Andres excavations uncovered maize cobs radiocarbon dated to the seventh century BC, and maize starch grains and residues have been detected on grinding stones from Middle Formative feasting contexts at the site. Nevertheless, carbon isotope data from human bone found in the same feasting refuse indicates that maize made up only about 50% of the diet. The Classic period Maya, by comparison, ate a diet of up to 90% maize.

Maize and sunflower consumption may have been a marker of Olmec ethnic identity. Some present-day Nahuatl-speakers believe that consumption of maize

Figure 4 Formative period botanical remains from San Andres, Tabasco. (a) Maize (Zea mays); (b) Chile pepper (Capsicum annuum); (c) sunflower achene (Helianthus annuus); (d) calabasa silvestre (Cionosicyos macrantha). Identifications and photographs by David Lentz.

Is a way of taking in the energy of the sun, and past sunflower seed consumption might have had similar connotations. Unequivocal representations of maize and sunflower are unexpectedly rare in Olmec iconography as well as in well-preserved archaeological deposits, however. One iconographic example of maize is an engraving on a royal scepter that shows maize poking out of the belly of a composite crocodilian animal, and the same element appears transformed into a glyph on a serpentine block from Cascajal that is inscribed with early writing.

Actual remains of Olmec offerings yielded a different emphasis, namely the abundance of the natural land. Botanical remains that Ponciano Ortiz and Maria del Carmen Rodriguez recovered from the sacred spring at El Manati included offerings of local wild vegetation (leaves, fruit pits, nuts) rather than cultigens.

World History

World History