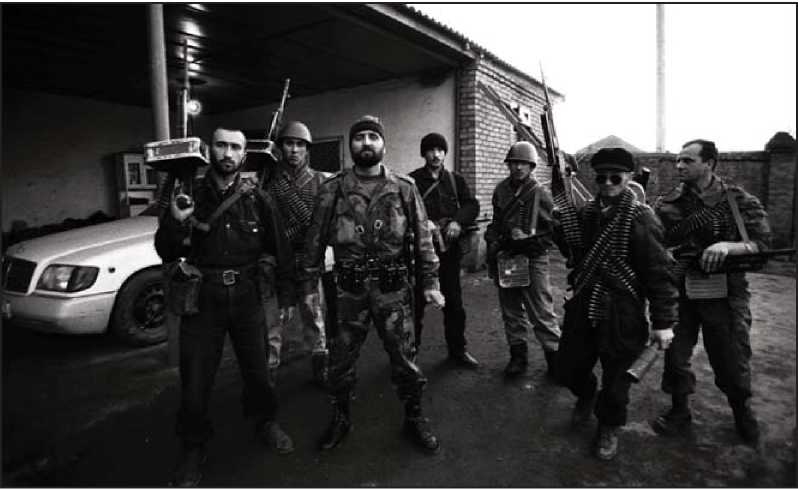

Grozny, 1 March 1995: a group of Chechen fighters still holding out against the Russians in the outskirts of the city, brandishing a motley collection of weapons including PK general-purpose machine guns, AKM-47 assault rifles and an RKG-3M antitank grenade. (© Christopher Morris/VII/Corbis)

Although the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria (ChRI) formally had its own security structures, they did not last long once the war began and the fight was soon in the hands of more irregular units, even if at times they were able to display unusually high levels of discipline and co-ordination. When the Russians invaded in 1994, they faced a Chechen Army, a National Guard and the Ministry of Internal Affairs (Russian bombers had essentially destroyed the Chechen air force on the ground on the eve of invasion). These forces were at once more and less formidable than they seemed: less formidable in that many of the units were far smaller than their titles suggested. The Army, for example, fielded a 'motor rifle brigade' that was actually little more than a company, with some 200 soldiers; the Shali Tank Regiment (some 200 men, with 15 combat-capable tanks, largely T-72s); the 'Commando Brigade' (a light motorized force of 300 men); and an artillery regiment (200 men, with around 30 light and medium artillery pieces). To these 900 or so troops could be added the 'Ministry of Internal

Affairs Regiment,' another light motorized force of 200 men. However, about two-thirds of the ChRI's field strength of 3,000 had been drawn from the so-called National Guard. This was a random collection of units, ranging from the gunmen of certain clans through to the personal retinues of particularly charismatic leaders as well as Dudayev's own guard. These had such picturesque names as the 'Abkhaz Battalion' and the 'Muslim Hunter Regiment', few of which truly reflected their real size or role.

However, this ramshackle assemblage of forces did have several significant examples. They knew the country well and while they were no longer quite the hardy outdoorsmen of the 19 th century, having adapted to the age of the car, central heating and college, their traditions did grant them a certain esprit de corps. They also knew their enemy, most having served their time in the Soviet or Russian military. Indeed, given the martial reputation and enthusiasm of the Chechens, a disproportionate number had served in the VDV or Spetsnaz, experience which would serve them well in the coming wars. In age, they spanned the full range from adolescents to pensioners, although the typical fighter was in his mid - to late twenties.

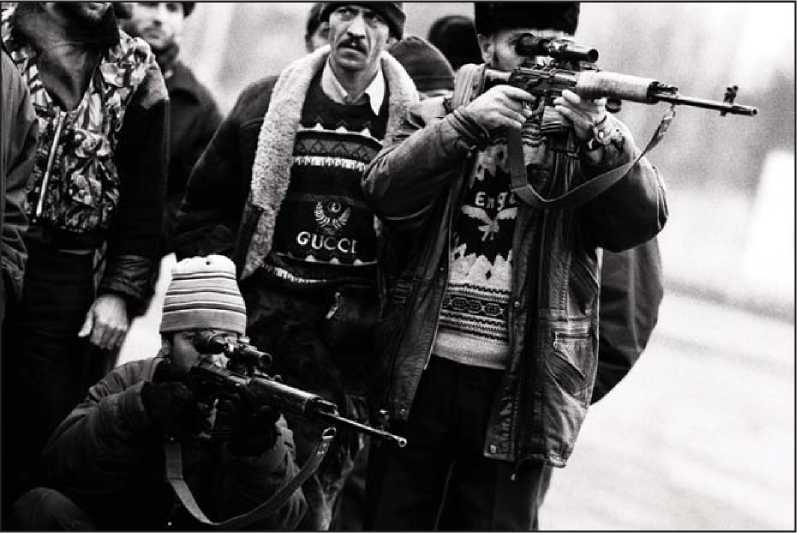

While some units still retained a more formal structure modelled on the Russian forces, in the main they fought in units of around 25 men broken into three or four squads. They were largely armed only with light personal and support weapons, especially AK-74 rifles, RPG-7 anti-tank grenade launchers, disposable RPG-18 rocket launchers, SVD sniper rifles, grenades and machine guns. However, thanks to that martial tradition, as well as the preceding years of rampant criminality which had seen guns smuggled into the country and state arsenals opened, they had plenty of those, not least the ammunition and spares the lack of which is often the guerrilla's bane.

Besides which, their numbers would quickly be swollen by volunteers from across the country, from the Chechen diaspora elsewhere in Russia and, eventually and ultimately counter-productively, from

Islamist militants from the Middle East. This would be an 'army' of warlords and their followings, even if during the First Chechen War and the early years of the Second there was still some sense of a command structure, largely anchored around the person of Aslan Maskhadov (1951-2005), the chief of staff of the Chechen military and later their elected president. Even so, this was a force whose size fluctuated by the season and the day, not least as individuals might take up arms for a particular operation and then return to their civilian activities until the next.

Above all, they were characterized by a fierce determination and excellent tactics. These were often unconventional, but rooted in an understanding of how their enemies operated. Knowing the Russian propensity for the artillery barrage, for example, in

Grozny 29 January 1997: a characteristically miscellaneous group of Chechen rebel fighters demonstrate their enthusiastic support for Aslan Maskhadov, the rebel general who assumed office as their elected president the following month. They are waving an equally characteristic mix of older and newer weapons: AKS-47 and AK-74 rifles and an RPK light machine gun with box magazine. (Vladimir Mashatin/EPA)

Rebel fighters aiming SVD Dragunov rifles during the battle for Grozny January 1995. SVDs are at best moderately accurate weapons, but a tradition of hunting and weapon-handling from a young age meant many Chechens could get the best out of them. (© Christopher Morris/VII/Corbis)

Urban warfare they 'hugged' Russian units, keeping within a city block or so of them so that the Chechen forces were safe from bombardments. Likewise, the Chechens were well aware that the guns of Russian

Tanks could not depress enough to engage basement positions, in which they built makeshift bunkers from which to attack Russian advances. Finally, they drew on their strengths, from sticking to using Nokhchy for their communications, knowing the Russians could intercept their radio traffic but not generally understand it, to drawing the federal forces into traps and ambushes in the cities and mountains that they knew so much better.

World History

World History