Agreement was signed in 1954, 900,000 Vietnamese nonCommunists in the North fied to the South. Many were fieeing from the severe treatment handed out to Vietnamese "traitors and landiords." Thousands had been kiiied by the Communist regime.

Keeping the Status Quo. The Indochina Treaty signed in

Geneva specified that elections would be held to determine the fate of both Vietnam and Laos. No foreign troops would be permitted inside either country to influence the outcome. The U. S.-supported Diem regime in South Vietnam had refused to sign the accord. Diem also refused to participate in the Vietnamese elections in 1956. Instead Diem proclaimed the Republic of Vietnam and became its president with U. S. support.

Eisenhower, however, had lived through the Korean conflict (see page 148) and had no desire to fight a war to unify Vietnam. He could tolerate the division of Vietnam, as long as the Communists stayed in the North and left the South alone. For a few years, at least, that is what happened. Both Diem in the South and Ho Chi Minh in the North worked to consolidate power within their own territories.

Under the terms of SEATO (the Southeast Asia Treaty

Organization), a U. S-led defense alliance, the United States continued to supply technical, militaiy, and financial aid to the South.

Kennedy Reacts. By the time President Kennedy took office in 1961, however, the situation was getting worse. Communist forces in Vietnam, and especially neighboring Laos, were becoming more aggressive. In 1961, Communist insurgents, the Vietcong, carried out attacks in the Kontum province of South Vietnam. The U. S. began talking about air strikes against North Vietnam and China.

Kennedy, however, was cautious. He sent another 100 military advisors to Vietnam as well 400 Special Forces soldiers. Additional U. S. military aid helped to bolster the Vietnamese Army. Kennedy also agreed to have U. S. troops stationed in Thailand. Things quieted down for a while, but the situation remained shaky.

A Corrupt Government. One of the biggest problems for the United States was that Diem’s rule was corrupt. Diem had taken control by force, and he had never been elected by the people of Vietnam, North or South.

During the late 1950s, as the Communists used terror to “purify” the North, Diem was wielding his own political bullwhip in the South. He installed village officials throughout the country and used corrupt means to control them. To his enemies he showed no mercy. He was particularly harsh with Communists in the South.

Diem's authoritarian control was not only a moral problem for the United States, it was also a practical problem. His corruption gave further ammunition—and power—to the Vietcong Communists in the South. Many times with encouragement from local peasants, they assassinated Diem’s village authorities.

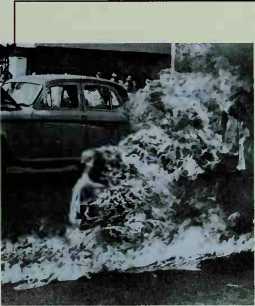

Ore than any other group, a few determined Buddhist monks brought about Ngo Dinh Diem's downfall In Vietnam. The monks were determined to protest Diem's persecution of Buddhists, and they did it in an unforgettable way.

On June 11,1963, a seventy-three-year-old monk from Hue, Thich Quang Due, had gasoline poured on himself in the middle of a Saigon street. He lit the gas, then burned to death as Saigon residents looked on.

After Thich Quang Due's death, other Buddhist leaders delivered a funeral address. They pleaded tor assistance from the U. S. military to

Help them in their plight in South Vietnam.

The protest caused a stir but no immediate changes, in mid-August, four more monks went up in flames. Eventually thirty monks and nuns died by self-immolation.

Diem's powerful sister-in-law, Madame Nhu, said: “Let them [the monks] burn, and we shall clap our hands.” But Diem was worried about the protests. He responded by attacking Buddhist temples. Thousands were arrested. For President Kennedy, the spectacle was too much. U. S. support for Diem evaporated. Vietnam’s ruler would soon join the monks in death.

Vietcong prisoners captured by South Vietnamese forces. Though Vietnam was largely a civil war, U. S. policy makers ne'er saw it that way.

Diem responded by locking up the peasants in fortlike hamlets, but this only made him more unpopular. Cries against Diem’s authority reached a screaming pitch when Buddhist monks set fire to themselves in public protests (see sidebar).

Military Challenges. The South Vietnamese Army was another problem. It was weak and poorly trained, no real match for the passionate Vietcong. Kennedy received much advice on how to relieve the problem. His military advisor. General Maxwell Taylor, suggested sending in a few thousand soldiers to help. The Joint Chiefs of Staff were more aggressive. They thought about 40,000 to

128,000 troops would "clean up" the situation.

Kennedy sent Vice President Lyndon Johnson on a fact-finding mission to Indochina. Upon his return, Johnson had determined that the United States needed to take a strong position in Vietnam, or Communists would soon take all of Southeast Asia.

Kennedy was unsure about how much of a threat the Communists posed in Indochina. He refused to make a major military commitment there. But he did continue to send troops, and he let it be knowTi in Febmary 1962 that they would fire back if fired upon.

Late in his administration, Kennedy withdrew support from the Diem regime. A group of unhappy Vietnamese generals, urged on by the United States, threw Diem out of office. Diem, along with his brother, was murdered the next day. A military junta, headed by General Nguyen Khanh, took power.

Johnson Takes Command. In November 1963, President

Kennedy was shot to death by an assassin in Dallas, Te. xas. He was replaced by Vice President Johnson. Johnson was wary of further involving the United States in the conflict but saw no real way of getting the country out of its commitment to the Vietnamese. "I don’t think it’s worth it,” Johnson said to an advisor, "and I don’t think we can get out.’’

Early in 1964, Johnson ordered military planes into Laos. In August, the destroyers USS Maddox and USS Turner Joy reported that they had been attacked by North Vietnamese torpedo boats in the Gulf of Tonkin off the North Vietnamese coast. Later investigations would lead to suspicions that the ships had not been attacked at all. Instead, it seemed possible that navy personnel had been confused by radar blips. No enemy vessels were discovered after the "attack.”

The day after the reports, Johnson ordered immediate strikes against naval bases, patrol boats, and oil depots along the North Vietnamese coast. The American raids cost the life of one navy pilot. Another became the first U. S. prisoner of war taken in Vietnam.

Tonkin Gulf Resolution, congress followed up the raid

With a resolution allowing the president to "take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States.” This blanket resolution would give President Johnson and his successors permission to wage war in Indochina for the next eight years. Congress would come to regret it.

By the end of 1964, about 20,000 U. S. soldiers were already in Vietnam.

World History

World History