Joker from pack of war-time cards depicts Hitler being burned by the flame from the torch of Liberty

Must be given a central role in all strategic thinking and planning, and not merely a peripheral role as hitherto. American logistical planning followed these determinants. Between 1940 and the end of 1944, the production of military aircraft rose from

23,000 per annum to 96,000. Military advisers also took note of the vital part played by Panzer divisions in the German victories. Accordingly, tank production was increased from 4,000 in 1940-41 to almost 30,000 in 1943.

Innovation and invention went hand in hand with greater efficiency in production. The assembly lines of the vast Detroit automobile factories were re-tooled and given over to the mass production of planes, armoured vehicles, and the engines of war. New methods of ship construction were devised and exploited, until American yards could claim to be launching a warship every day. The combination of American engineering and technology with boundless resources of coal, iron, and steel soon tipped the economic balance of power, even though Hitler’s military successes in Europe and North Africa still made the outcome of the war uncertain.

Meanwhile, as Great Britain faced Hitler alone in Western Europe, Churchill took pains to further the Anglo-American alliance. British military secrets were passed to United States political and military experts in London, and joint consultation at the level of strategic planning became one of the less publicized aspects of Churchill’s direction of the war. In August 1941 Roosevelt and Churchill held secret meetings aboard the US cruiser Augusta off Newfoundland. From these meetings the two leaders issued the Atlantic Charter, a declaration of common aims and purposes. Among them were opposition to all forms of territorial aggrandizement, support for the right of all peoples to choose their own form of government, freedom from want and fear, freedom of the seas, and the disarmament of aggressor nations until a permanent peace-keeping organization was securely established.

By now, the United States was firmly on the side of the Allies, though Hitler was prudently avoiding a direct confrontation with the United States. Events moved a step nearer war with Germany when a U-boat attacked the USS Greer apd brought American naval strength into direct conflict with German naval vessels. From then on, American warships had the President’s orders to 'shoot first’.

On 7th December, when Japan perpetrated its 'day of infamy’ by its attack on the American fleet at Pearl Harbour, the remaining vestiges of isolationist sentiment in the United States vanished. America now had a common cause with the democracies against the Axis powers. On 8th December, with only one dissenting voice in Congress, the United States declared war on Japan. Three days later Germany and Italy declared war on the United States, and the President and Congress recognized a state of war with these nations. The 'arsenal of democracy’ now brought its army, its navy, and its air force to the task of defeating the Axis powers. The final result of the war was no longer in doubt.

America’s economy is geared to war American industry turned to full-scale wartime production. New plants were constructed in a matter of days. Six million women were added to the labour force as selective service took labour away from factory and farm. Older men returned to work and the unemployed were quickly drawn into the national effort. Between 1940 and 1943 the total labour force increased by eight million, from forty-seven to fifty-five million. The working week was increased from forty to forty-eight hours. By 1942, more fighter planes were being produced in one month than had been produced in the whole of 1939. Between Pearl Harbour and the end of the war the United States produced more* than 295,000 aeroplanes. Germany’s production was less than a third of this, a fact which made it certain that Germany would lose the mastery of the skies.

Not all of American expertise was given to the production and development of conventional weapons. As early as the autumn of 1939, when Albert Einstein warned President Roosevelt that Germany was seeking to develop an atom bomb, federal funds were channelled into an atomic energy programme. Research and devcdoj)-ment proceeded with the utmost secrecy at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Los Alamos, New Mexico. In December 1942 physicists produced a controlled chain reaction in an atomic pile at the University of Chicago. Following this, federal funds of more than $2,000 million were poured into th(> development of an atomic bomb, although the first successful test did not take place until after the defeat of Germany in 1945.

By the autumn of 1943 Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin realized that the defeat of Germany was only a matter of time. The 'Big Three’ discussed plans for a post-war settlement in conferences at Tehran and later at Yalta. Roosevelt and Churchill developed a close personal friendship in Anglo-American discussions at Casablanca and at Washington in 1943. Two further meetings at Cairo that same year cemented their friendship. Their common language, and the fact that both Roosevelt and Churchill found Stalin a somewhat impenetrable figure, inevitably brought the two English-speaking allies into closer counsel. Churchill, needless to say, was entirely happy at this development, even though the American President had doubts about Great Britain’s apparent aim of preserving her Empire after the war.

In the field, military commanders did not always see eye to eye on strategy or tactics. When General Dwight D. Eisenhower was made Supreme Commander for the invasion of Western Europe, his commander in the field. General Montgomery, was a loyal but not an altogether uncritical colleague. Nevertheless, combined operations worked remarkably smoothly on land, sea, and in the air.

The final victory over Germany owed something to a common language, but much more to a common set of ideals. If Franklin Roosevelt had not declared the United States the 'arsenal of democracy’ in December 1940; if he had not used his presidential power to hurry the Lend-Lease Bill through Congress, we may doubt —as Churchill doubted —that Great Britain could have survived her 'darkest hour’. It would be easy for Europeans to underestimate the skill and determination required by Roose* velt to bring the United States into the war on the side of the Allies. It is worth recalling that on the eve of the presidential election of 1940 Roosevelt’s opponent wrung from him a categorical promise to the American people that: 'Your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars.’ Fortunately for Great Britain, fortunately for Europe, President Roosevelt did not keep this promise.

''Ml

The Desert War

In the months before the outbreak of war the importance of the Middle East in British grand strategical planning gradually increased. As early as spring 1939 the British and French staffs decided that in the event of war Italy rather than Germany would offer the best prospects for Allied offensive action in the early years. The Italian colony of Libya was sandwiched between the French in Tunisia and the British in Egypt, while Italian East Africa would be a wasting asset cut off from home. At the same time British and French forces in Palestine, Iraq, and Syria were well placed to support Turkey.

The fall of France in June 1940 obliterated these happy prospects. At once the balance of naval and military power swung in Italy’s favour —indeed it was only the certainty that France was already beaten that induced Mussolini, the Italian dictator, to declare war. Now it was the British whose position in the Middle East was precarious. Against some 500,000 Italian troops, the Commander-in-Chief Middle East Land Forces, General Sir Archibald Wavell, could muster only some

60,000 to defend a theatre of war 1,700 miles by 2,000 miles, a theatre which encompassed nine countries from Iraq to Somaliland.

The importance of the Middle East to the British no longer lay in the Suez Canal route to the East, because the neutralization of the French fleet left the Royal Navy alone too weak to command the whole Mediterranean sea-route from Gibraltar to Egypt. The importance lay in the oil of the Persian Gulf. Its loss would throw Great Britain into dependence on dollar oil from the Americas, while on the other hand its possession by the Axis powers would solve their chronic fuel problems.

The most direct and serious threat to the oil was posed by the Italian army in Libya, some 300,000 men; and the most suitable place to parry the threat was Egypt. From a naval standpoint, the Egyptian port of Alexandria was the base for British sea-power in the eastern Mediterranean, while the Suez Canal was its emergency exit. From a military point of view Egypt

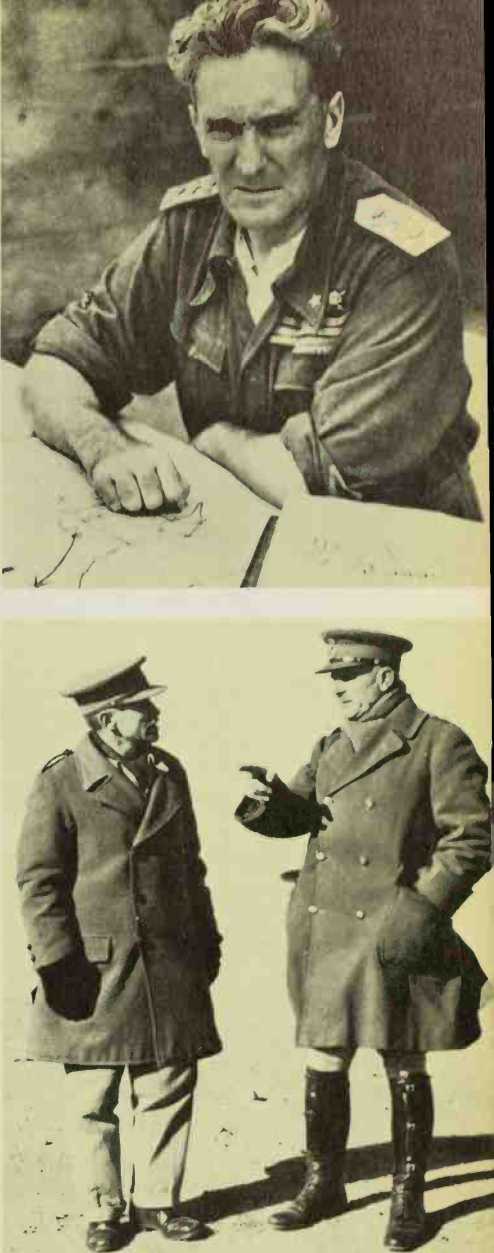

Left: Supply and defence for the Afrika Korps: Junkers 52 transports and Me 110 fighters on a Luftwaffe base in the desert. Right: The Campaign generals. Top: Graziani, the Italian commander. Centre: An immaculately attired Wavell (right), talks to his Western Desert Force Commander O’Connor, January 1941. Bottom: Auchinleck (right), with New Zealand General Bernard Freyberg

Simultaneously blocked the invasion routes up the Nile into the Sudan, eastwards to the Persian Gulf, and northwards into Syria towards Turkey. Retention of Egypt would also hold enemy heavy bombers out of effective range of the Gulf oilfields. Lastly Egypt offered many advantages as a main theatre base —good ports and communications, abundant water and labour.

Thus the whole North African campaign from 1940 to 1943 arose from the need to defend the Persian Gulf oilfields from Egypt — and Egypt from the Western Desert. The area of desert where the battles of 1940-42 were fought stretches nearly 400 miles from El Alamein in the east to Derna in the west. The only road follows the coast. The railway from the Nile Delta ended at Mersa Matruh until extended by the army. The one dominating physical feature is a 500-ft escarpment facing north to the coastal plain, and descending from the limestone plateau where the armies manoeuvred. The desert is a featureless waste of gravel and scrub, dotted with ancient cisterns and tombs of sheiks. Armies therefore moved almost with the freedom of fleets, navigating by compass and the stars. However all supplies and water had to be imported. Long columns of trucks from horizon to horizon sustained the fighting troops, while dumps and water pipelines were the jugular veins exposed to enemy armour. The Desert Campaign constituted a unique episode in the history of warfare —war in its purest form, unencumbered by civilians and habitations except along the coast, or by natural obstacles other than the escarpment.

Wavell appointed Major-General R. N. O’Connor to command Western Desert Force. O’Connor, a small, immensely alert and alive man, had a reputation for high intelligence and unorthodoxy. He soon won and always retained the complete confidence of his officers and men. Immediately Italy entered the war on 11th June 1940, raids and ambushes on Italian territory established British moral superiority. However, Wavell’s great weakness forced him to stand everywhere on the defensive for the time being, and so Western Desert Force was withdrawn to Mersa Matruh to await the expected Italian invasion of Egypt. This materialized only on 15th September after Mussolini had repeatedly prodded his reluctant commander. Marshal Rodolpho Graziani. Graziani halted after advancing some sixty miles and proceeded to organize his army in a series of defended camps stretching some fifteen miles inland from the coast at Sidi Barrani.

'I'

I

Italians surrendering at Bardia. Their strength of numbers was not enough to counter superior British leadership and equipment. O'Connor’s 36,000-strong force had already taken 38,000 prisoners in its December offensive, and then in January took another 40,000 in Bardia. The Italians often showed immense individual heroism, but consistently failed where large-scale organization was demanded

It was his intention to march on the Nile Delta once he had huilt up supplies, metalled the coast road, and laid water pipelines. O’Connor on his part had prepared a model defensive battle at Matruh for Graziani’s reception, to culminate with a counter-stroke hy all the British armour. But Graziani never came. Instead the British prepared their own offensive.

Although Great Britain herself was threatened by invasion, and her home defence forces were terrifyingly weak, the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, took the great risk of shipping 150 tanks to the Middle East. For it was the Middle East that was now the only place where there was contact between British and enemy ground forces, and attacking the Italians offered the best hope of a resounding victory to set against the catastrophes of the year. This belief was shared by the c-in-c. General Wavell, whose selected victim was the Duke of Aosta and his garrison of Italian East Africa, cut off from aid and reinforcements from Italy. However, before Wavell could open a campaign so far from Egypt, the threat from Graziani had to be neutralized. He therefore ordered O’Connor to plan a spoiling attack to last five days, after which O’Connor’s infantry division would be wanted for Eritrea. O’Connor instead aimed at a decisive victory.

There were two groups of Italian fortified camps, separated by a gap in the centre, the Tummars and Nibeiwa near the coast, and the Rabia and Sofafi camps further inland, garrisoned by three divisions with tanks in support. Well to the rear and widely separated were another six divisions. No one could foretell how the army of f’ascist Italy would fight. Although Italian tanks were known to be poor, their artillery outnumbered the British by two to one.

O’Connor’s own forces numbered 36,000 men, organized in two divisions, 4th Indian (infantry) and 7th Armoured, together with a mixed group called Selby Force after its brigadier. 4th Indian Division, together with fifty-seven heavily armoured T’ (infantry co-operation) tanks, was to assault, while 7th Armoured, with its cruiser-tanks, was to protect the British flank and then exploit and pursue. Western Desert Force was thoroughly well-trained, with a high proportion of professional soldiers. O’Connor’s plan was bold and unorthodox. The assault force penetrated through the gap in the centre of the Italian camps and assaulted from the west, the Italian rear. At the same time British artillery, without waiting to register, opened heavy surprise fire from the east to demoralize and confuse the Italians. The British force had thus to assemble within the enemy’s defence zone and make an approach march through his defences. The risks paid splendidly. On the first day of the offensive (9th December 1940), the Italians were taken completely by surprise, and although they fought stoutly, their camps fell one by one, Nibeiwa first, then the Tummars, while the British armour cut the coast road between Sidi Barrani and Buq Buq. The remaining camps were abandoned and the armour pursued the routed enemy towards the Libyan frontier.

In two days’ fighting O’Connor had ended the threat to Egypt, smashed two Italian corps, taken 38,000 prisoners (including four generals), 73 tanks, and 37 guns at the cost of only 624 killed, wounded and missing. It was exactly the kind of victory the British at home needed in the grim winter of the Blitz. It also fulfilled Wavell’s purpose and enabled him to withdraw the Indian division for use in Eritrea.

This was one of the decisive moments of the whole North African campaign. Wavell’s strategic intention in the desert was defensive; O’Connor was expected now to halt, although not specifically ordered to do so. However, O’Connor pressed on with the forces remaining to him. By 16th December he had closely invested the fortress of Bardia, just inside Libya. His continued success induced Wavell to send him the understrength 6th Australian Division in place of the Indiafis. Thus the strategy of the campaign changed from the defensive to the offensive, and the consequences were to be far-reaching.

On 3rd January 1941 13th Corps (as Western Desert Force had been renamed) attacked Bardia and captured it in one day. The bag included 40,000 prisoners, 13 medium and 115 light tanks, 400 guns, and 706 trucks (a windfall for O’Connor). The British armour pressed on to cut off Tobruk, the next port and fortress along the coast. Like Bardia, Tobruk fell in a single day, on 22nd January 1941. This time the bag comprised 25,000 prisoners, 208 guns, 23 medium tanks, and 200 trucks.

In front of O’Connor now was the bulge of Cyrenaica, the Jabal Akhdar, a fertile region of hills colonized by Italian settlers, and beyond it the city of Benghazi. The remnants of Italian X Army were seeking to escape into Tripolitania along the coast road, which wound round the Jabal Akhdar to the Gulf of Syrte. Although O’Connor’s force was now almost worn out mechanically, he flung it along appalling and unreconnoitred desert tracks south of the Jabal to try to reach the coast road ahead of the Italians and bar their retreat. On 5th February 1941 his trap closed with half an hour to spare. P’or two days the Italians strove desperately to break through, but

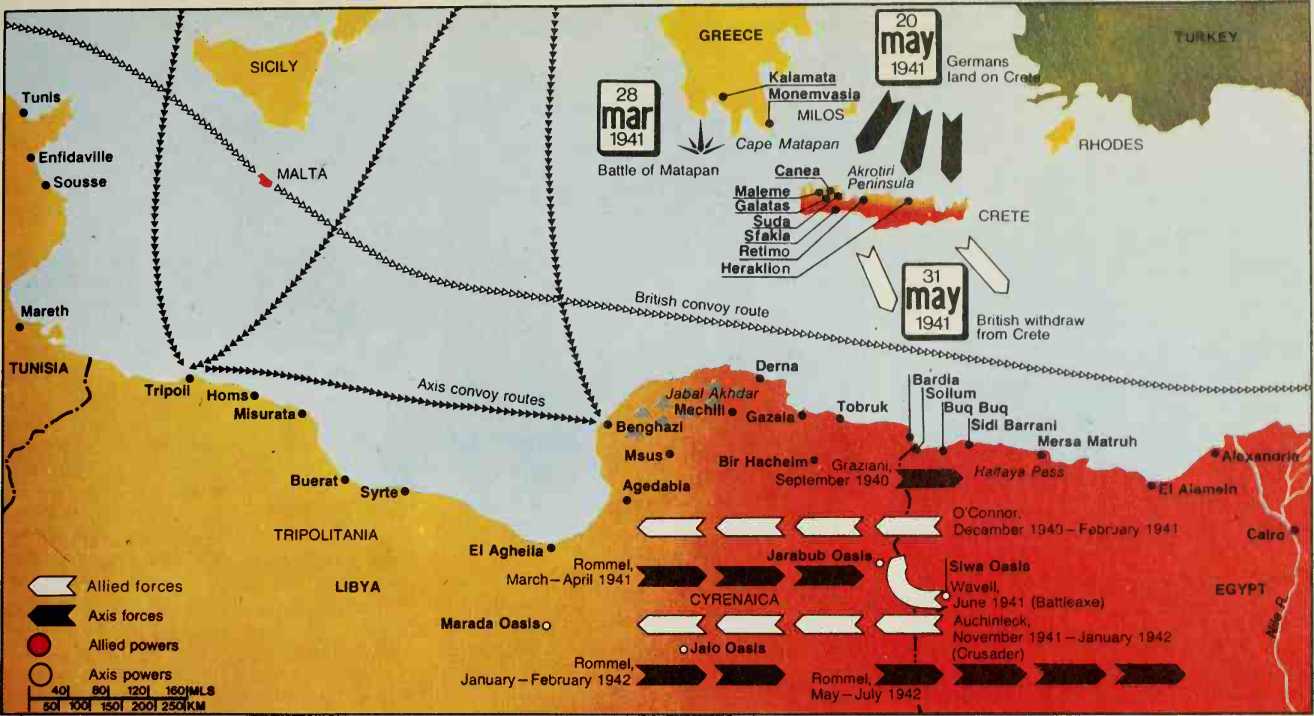

The war in the Mediterranean and North Africa from 1940 to 1942, showing the loss of Crete and the struggle for the Western Desert. O’Connor’s devastating successes against the Italians were not followed through because of the need to help Greece. Rommel had his chance. After a year-long duel, during which he was thrown back by Auchinleck’s offensive, Rommel finally broke through into Egypt

Failed. In this Battle of Beda Fomm O’Connor achieved that rare military phenomenon, a complete victory, for the X Army had been utterly destroyed. In ten. weeks O’Connor had taken 130,000 prisoners, 400 tanks, and 1,290 guns.

It seemed to O’Connor that Tripolitania, now almost defenceless, might also fall to a swift advance, and the whole of Italian North Africa be cleared. Thus a campaign that had begun with the defence of Egypt was now pointing towards the destruction of Italian power, first in Africa, later perhaps at home. However, the British government decided that instead of striking at Tripoli, the bulk of O’Connor’s veterans should be made available to aid the Greeks against an expected German invasion. O’Connor went on sick leave and 13th Corps was broken up. The British never recovered the professionalism and cohesion of this matured formation.

There is little question that the decision not to drive on to Tripoli at the beginning of February 1941 was one of the most unfortunate of the war. The aid to the Greeks achieved nothing in the event, while on 12th February Lieutenant-General Erwin Rommel arrived in Tripoli with an advance party of German troops. O’Connor’s victories, by being halted in mid-career, had only served to draw the Germans into North Africa, a vastly more potent danger to Egypt than the Italians could ever have been.

The Germans in North Africa The danger became swiftly manifest. On 31st March 1941, long before either Wavell or the German High Command itself believed he could be ready, Rommel attacked the British round El Agheila. The bewildering speed and agility of Rommel’s advance brought about the collapse of the green formations that had replaced O’Connor’s veterans. O’Connor himself, sent up to advise his successor Neame, was captured along with Neame. The whole of Cyrenaica was lost except for Tobruk which was cut off and besieged, and Rommel only halted, just over the Egyptian frontier, because he had outrun his supplies.

Henceforth the duel with Rommel in the Western Desert was more and more to fascinate the British, especially the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill. The Western Desert was the only place where the British Empire could fight Germany on land. It was now therefore less of a case of defending Egypt than of winning a great victory over Rommel’s Panzer Group Africa; of, in fact, attempting again in very different circumstances to carry out O’Connor’s intention of completely clearing North Africa.

British prospects were not good. The British Army had begun to prepare for modern tank warfare at least five years later than the Germans, and lacked German operational experience. The British Empire forces had been hastily and recently expanded. British military doctrine and staff methods did not equal those of Germany. These weaknesses were compounded again and. again when half-raw divisions had to be committed to battle in haste because of the hunger at home for victories, or at least offensive action. British equipment, too, bore the signs of late and hasty rearmament. The British cruiser-tanks were highly unreliable mechanically, while the four-gallon petrol can wasted untold quantities of fuel because of its flimsiness. These British qualitative inferiorities in skill and equipment were never understood or accepted by the Prime Minister, who repeatedly urged his commanders-in-chief in the Middle East to attack before they felt ready. The consequences of such attacks were demonstrated in June 1941, when an offensive (Battleaxe) was heavily defeated. It was Battleaxe that finally doomed Wavell, already in disfavour.

His successor was General Sir Claude Auchinleck, of the Indian Army, a big man with a strong but warm personality. He too was immediately pressed for an offensive, but remained adamant that 1st November was the earliest that the green reinforcements and untried equipment now pouring into Egypt could be shaped into an army fit to meet Germans in battle. In the event, the offensive, code-named Crusader, was launched on 18th November, and its course was to bear out all Auchinleck’s misgivings. Except in dogged courage, 8th Army (as the desert forces had now become) showed itself - generally inferior in operational skill at every level to XV and XXI Panzer Divisions (the Afrika Korps), and 90th Light Division (trucked infantry). German tanks proved themselves superior mechanically and German tank recovery services were also better organized.

According to the British plan, the infantry divisions of 13th Corps would make an attack on the fixed Axis defences round the Halfaya Pass (leading up the escarpment from the coastal plain), while the armour of 30th Corps would swing wide through the desert, fight and beat the German armour, and relieve Tobruk. 8th Army fielded in an augmented 7th Armoured Division 453 gun-armed tanks against fewer than 200 German tanks in XV and XXI Panzer Divisions, and some 130 Italian. The British plan soon fell apart into sprawling actions all over eastern Cyrenaica, with

Both sides mixed up in a way unprecedented in war. A sheik's tomb, Sidi Rezegh, was the focus for repeated encounters, and gave the alternative name to the Crusader battles.

At first it seemed that the British had won the armoured battle. Then news seeped back of appalling losses and stalled attacks. It was a proof of the superiority of German tactics and of British inexperience. While the British tried to charge home, cavalry-style, the Germans fought defensively, drawing the British on to their antitank guns, especially the deadly 88-mm guns adapted from an anti-aircraft role.

The 8th Army commander, Lieutenant-General Sir Alan Cunningham, who had never commanded such masses of armour or troops in battle before (what British soldier had?), was near a breakdown. He believed that the offensive had failed, and that unless the army fell back into Egypt, it would be destroyed and the Nile Delta endangered. Auchinleck relieved him and ordered the offensive to go on. In Cunningham’s place, Auchinleck temporarily appointed Major-General Neil Ritchie, his Deputy Chief of the General Staff in Cairo, a burly, phlegmatic man who loyally carried out Auchinleck’s order to grip Rommel and wear him down.

Rommel’s reserves of tanks were smaller than the British and he was denied supplies from Italy. Gradually the stubborn British dominated the battlefield. Tobruk was relieved. The Germans slowly fell back to El Agheila (5th-6th January 1942). Despite its rawness 8th Army had taken

36,000 prisoners and reduced the German tank strength to thirty. Crusader was the first British victory over the Germans in the Second World War.

It now proved no more possible for Auchinleck to push swiftly on into Tripoli-tania than for Wavell a year earlier. Whereas Greece had competed with the desert for resources in 1941, it was now to the Far East, under heavy Japanese attack, that Auchinleck lost two divisions and much equipment. Once again Rommel took advantage of the British pause in front of the Agheila position. On 21st January 1942 he emerged from his defences to give one of his most brilliant displays of op-

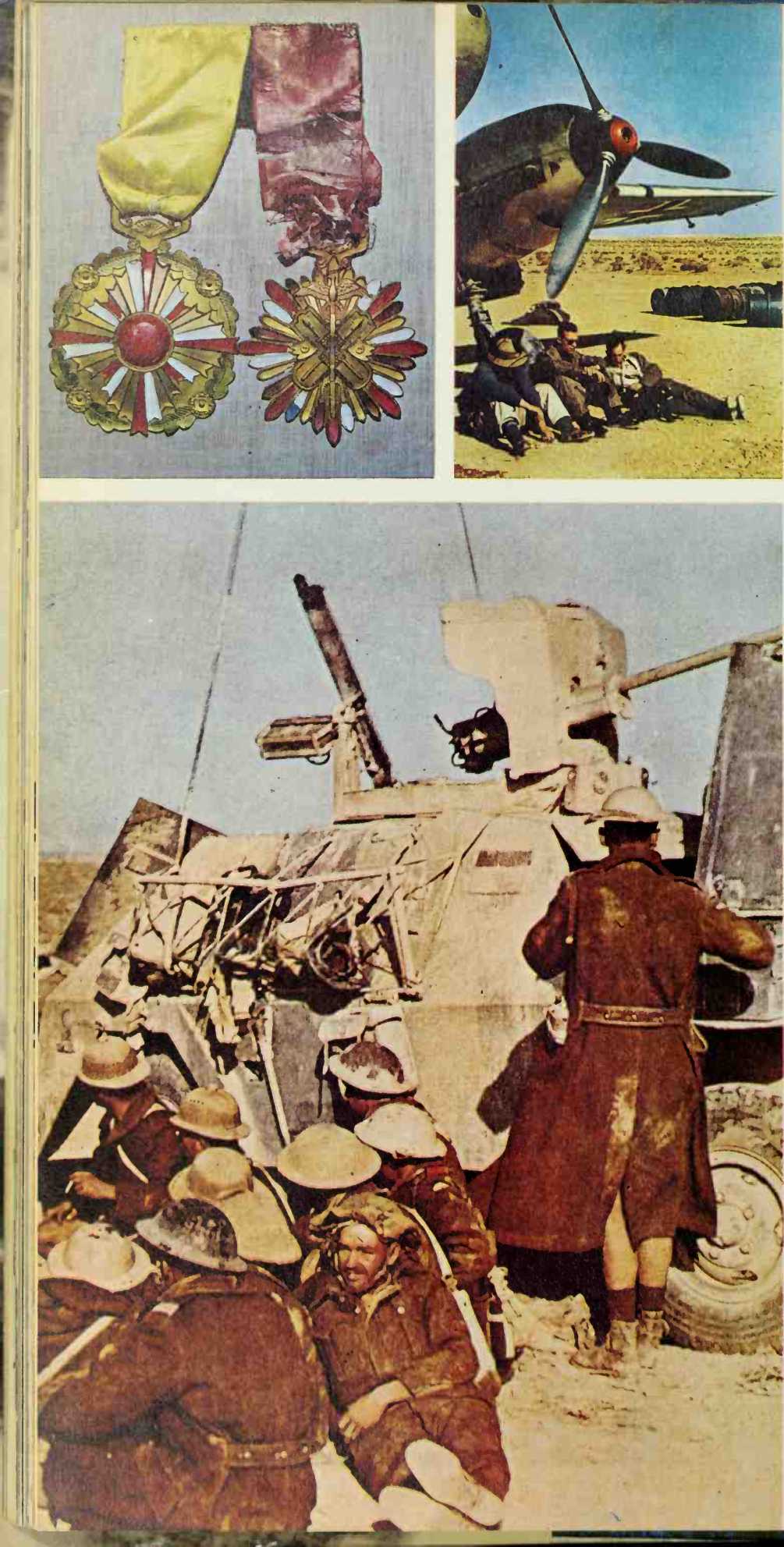

Abovc left: Worthless medals used by the Italians as rewards to local population in North Africa. Above: German airmen resting in the desert. Left: British troops captured by Germans in North Africa.

World History

World History